- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

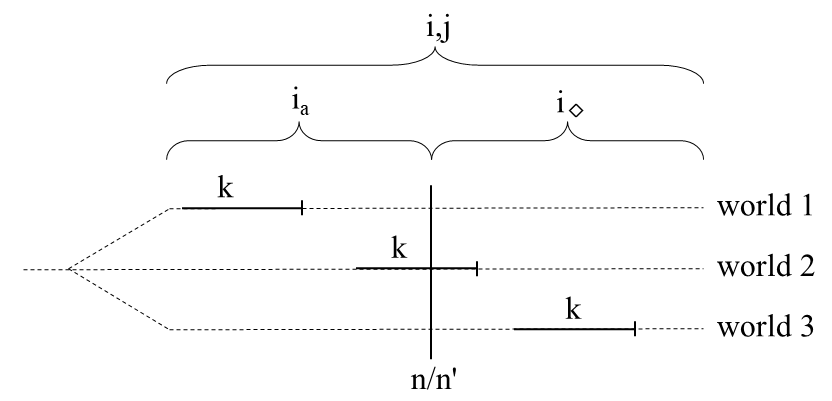

This section discusses the use of the perfect tenses. We will assume that the default interpretation of these tenses is as given in Figure 25, and that eventuality k can thus precede, overlap, or follow n/n'; in other words, the default interpretation of the present j of eventuality k is identical to the present/past i of the speaker/hearer. The perfect tense thus differs from the simple tenses discussed in 1.5.4.1 only in that eventuality k is presented as completed within j.

We will further argue that the more restricted and special interpretations of the perfect tenses do not need any special stipulations, but follow from the interaction of the three kinds of linguistic information listed in (396).

| a. | Temporal information (tense and adverbial modification) |

| b. | Modal information (theory of possible worlds) |

| c. | Pragmatic information (Grice’s maxim of quantity) |

The discussion will mainly focus on the present perfect, since we assume that the argumentation also applies to the past perfect; however, we will see that the use of the past perfect sometimes triggers some special effects.

- I. Default use

- II. Non-linguistic context: monitoring of k

- III. Adverbial modification and Aktionsart

- IV. Multiple events

- V. Habitual and generic clauses

- VI. Conditionals and hypotheticals

- VII. Conditionals and counterfactuals

- VIII. Denial of the appropriateness of a nominal description

- IX. Conclusion

The perfect tense situations presented in Figure 25 usually arise when the speaker is giving a second-hand report. If Els promised the speaker yesterday that she would read the paper under discussion today, the speaker can utter example (397) at noon to report this promise. In this case it is irrelevant whether Els has actually read the paper, is still reading it, or will start reading it later in the day.

| Els heeft | vandaag | mijn artikel | gelezen. | ||

| Els has | today | my paper | read | ||

| 'Els will have read my paper today.' | |||||

That the present perfect can also refer to an eventuality overlapping or following n is a direct consequence of our claim that Dutch does not express the binary feature [±posterior] within its verbal system. This finding opts for the binary tense theory over Reichenbachian approaches to the verbal tense system, since the latter have no means of expressing it and must therefore treat such cases as special or unexpected uses of the present perfect.

The choice between past and present perfect is often related to the temporal location of some other event. Consider the examples in (398): the present tense in example (398a) requires the examination to be part of the present-tense interval (and indeed strongly suggests that it will take place in the non-actualized part of that interval), whereas (398b) strongly suggests that the examination is part of the past-tense interval preceding speech time n.

| a. | Ik | heb | me goed | voorbereid | voor het tentamen. | |

| I | have | me well | prepared | for the exam | ||

| 'I have prepared well for that exam.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | had | me goed | voorbereid | voor dat tentamen. | |

| I | had | me well | prepared | for that exam | ||

| 'I have prepared well for that exam.' | ||||||

Similarly, an example such as (399a) can be used to inform the addressee that the window in question is still open at speech time n, whereas (399b) does not have this implication, but can be used e.g. in a story about a burglary that happened in some past-tense interval.

| a. | Ik | heb | het raam | niet | gesloten. | |

| I | have | the window | not | closed | ||

| 'I have not closed the window.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | had | het raam | niet | gesloten. | |

| I | had | the window | not | closed | ||

| 'I had not closed the window.' | ||||||

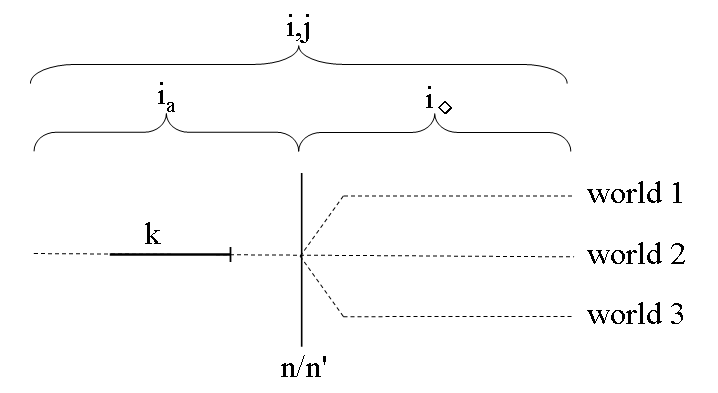

The interpretation of example (397) can be limited by pragmatic considerations. In the context given above, the split-off point of the possible worlds precedes present-tense interval i and thus also speech time n. However, if the speaker is able to monitor Els’ actions during the actualized part of the present-tense interval ia, then the split-off point of the possible worlds coincides with n, and in this case example (397) would normally be used to refer to the situation shown in Figure 28, in which eventuality k precedes n; cf. Verkuyl (2008).

That k usually precedes n in the situation sketched above is illustrated in (400a). Recall that 1.5.4.1, sub II, referred to this preferred reading of (400a) to explain why the present in (400b) cannot normally be used to refer to an event preceding n.

| a. | Jan heeft | vandaag | gewerkt. | k precedes n | |

| Jan has | today | worked | |||

| 'Jan has worked today.' | |||||

| b. | Jan | werkt | vandaag. | k follows or overlaps with n | |

| Jan | works | today | |||

| 'Jan will work today.' | |||||

Examples such as (401a), in which the completion of eventuality k can be located in the non-actualized part i◊ of the present, and indeed must be located there if the speaker knows that Els has not yet finished the paper at speech time n, may help us better understand how the more restricted interpretation in Figure 28 arises. As will be discussed in more detail in Subsection III, temporal adverbial phrases can modify the precise location of eventuality k within interval j; the temporal adverbial phrase om drie uur indicates that the completion of the eventuality of Els reading the speaker’s paper will take place before 3 p.m.; cf. also Janssen (1989). The reason why example (401b) does not normally refer to eventualities following n in the situation sketched in Figure 28 is that the relevant point in time at which eventuality k must be completed is taken by default to be speech time n; that this is indeed the default reading can be seen from the fact that making this point in time explicit, e.g. by adding the adverb nunow, can only be done if the speaker intends to emphasize that the relevant evaluation time is indeed the speech time.

| a. | Els heeft | mijn artikel | om drie uur | zeker | gelezen. | |

| Els has | my article | at 3 p.m. | certainly | read | ||

| 'Els will have read my article by 3 p.m.' | ||||||

| b. | Els heeft | mijn artikel | gelezen. | |

| Els has | my article | read | ||

| 'Els has read my article.' | ||||

Although an account along these lines seems plausible, the examples in (402) show that it cannot be the whole story. In these examples, the adverb vandaagtoday again modifies j and the adverbial phrase tot drie uuruntil 3 p.m. restricts the location of eventuality k to some subinterval of j preceding 3 p.m. However, in situations in which the speaker is able to monitor eventuality k, present-perfect examples such as (402a) are normally used when k is completed before speech time n (i.e. it would be odd to use this example at 1 p.m.), whereas simple present examples such as (402b) are normally used when k is completed after n.

| a. | Vandaag | heeft | Jan tot drie uur | gewerkt. | n > 3 p.m. | |

| today | has | Jan until 3 p.m. | worked | |||

| 'Today, Jan has worked until three p.m.' | ||||||

| b. | Vandaag | werkt | Jan | tot drie uur. | n < 3 p.m. | |

| today | works | Jan | until 3 p.m. | |||

| 'Today, Jan will work until 3 p.m.' | ||||||

The fact that (402a) cannot have a future interpretation suggests that something is missing. We return to this in Subsection IIIB, which aims to fill this gap by showing that Aktionsart also restricts the temporal interpretation of the perfect tenses.

As in the case of the simple tenses, the temporal interpretation of the perfect tenses can be restricted by adverbial modification. However, it seems that the situation is somewhat more complex, since also Aktionsart can restrict the interpretation of the perfect tenses: more specifically, atelic predicates differ from telic ones in that they allow a future interpretation of the perfect only under very strict conditions.

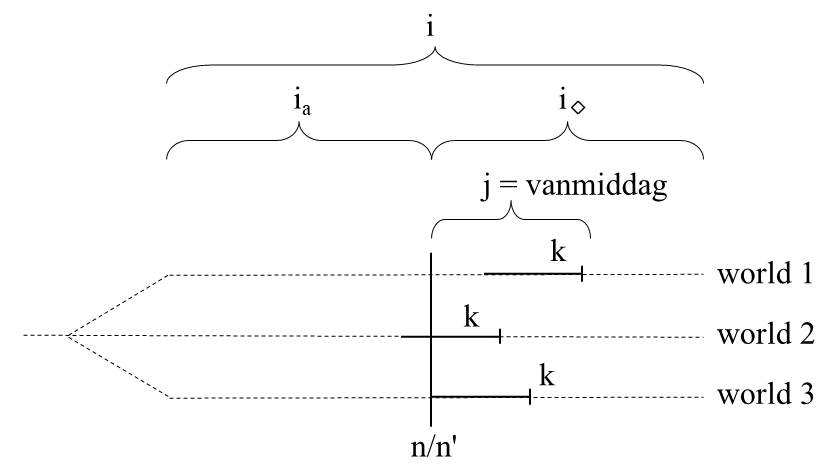

The default interpretation of perfect examples such as Els heeft mijn artikel gelezenEls has read my article in Figure 25 can also be restricted by grammatical means, such as the addition of temporal adverbial phrases. Assuming that the examples in (403) are uttered at noon, example (403a) expresses that Els finished reading the paper in the morning (before speech time n) and (403b) that Els will finish reading the paper in the afternoon (after speech time n).

| a. | Els heeft | vanmorgen | mijn artikel | gelezen. | |

| Els has | this.morning | my paper | read | ||

| 'Els has read my paper this morning.' | |||||

| b. | Els heeft | vanmiddag | mijn artikel | gelezen. | |

| Els has | this.afternoon | my paper | read | ||

| 'Els will have read my paper by this afternoon.' | |||||

Since the perfect tense focuses on the termination point of the event, it is irrelevant for the truth of example (403b) whether the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb overlaps or follows speech time n. This means that the adverbial phrase vanmiddagthis afternoon is compatible with eventualities that overlap as well as with eventualities that follow n. And, assuming that the speaker is underinformed about the actual situation, example (403b) can refer to the situation in Figure 29.

The effect of the addition of temporal adverbial phrases is thus that time interval j, which must contain the termination point of the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb, is restricted to a subpart of i, which may be located in the actualized part of the present/past-tense interval, as in (403a), or in its non-actualized part, as in (403b).

However, temporal adverbial phrases do not necessarily restrict the present j of eventuality k, but can also modify k itself. The latter can be observed in example (404), in which vanmiddagthis afternoon modifies j and the adverbial PP voor het collegebefore class modifies k, with the result that the termination point of eventuality k must be located within the time interval j denoted by vanmiddag, and must precede the moment in time where the referent of the nominal complement of the preposition voor is located.

| Ik | heb | vanmiddag | je artikel | voor het college | gelezen. | ||

| I | have | this.afternoon | your paper | before the class | read | ||

| 'I will have read your article this afternoon before class starts.' | |||||||

In (404) the modifier of j precedes the modifier of k, and this seems to be the normal state of affairs (at least in the middle field of the clause). In fact, it seems that the two also take different positions with respect to the modal adverb; the examples in (405) show that modifiers of j usually precede modal adverbs such as waarschijnlijkprobably, whereas modifiers of k must follow them.

| a. | Jan was gisteren/vandaag | waarschijnlijk | om 10 uur | vertrokken. | |

| Jan was yesterday/today | probably | at 10 o’clock | left | ||

| 'Jan had probably left at 10 oʼclock yesterday/today.' | |||||

| b. | Jan is morgen | waarschijnlijk | om 10 uur | al | vertrokken. | |

| Jan is tomorrow | probably | at 10 o’clock | already | left | ||

| 'Jan will probably already have left at 10 oʼclock tomorrow.' | ||||||

That the modifier of k must follow the modal adverbs can also be supported by the two examples in (406). In (406a) the adverbial phrase om tien uur precedes the modal adverb, and the most striking reading is that the leaving event took place before 10 o’clock; the adverbial phrase thus indicates the end of time interval j within which the eventuality must be completed. In (406b), on the other hand, the adverbial phrase om tien uur follows the modal adverb, and the most striking reading is that the leaving event took place at 10 a.m. Note that English has no similar means of distinguishing between the two readings; the translations of the examples in (406a&b) are truly ambiguous; cf. Comrie (1985:66).

| a. | Jan was om 10 uur | waarschijnlijk | al | vertrokken. | |

| Jan was at 10 o’clock | probably | already | left | ||

| 'Jan had probably already left at 10 oʼclock.' | |||||

| b. | Jan was waarschijnlijk | al | om 10 uur | vertrokken. | |

| Jan was probably | already | at 10 o’clock | left | ||

| 'Jan had probably already left at 10 oʼclock.' | |||||

It seems that adverbial modification of k in present-perfect examples with a future reading has the effect of placing the termination point between speech time n and the time (interval) referred to by the adverbial phrase. This can be seen from the contrast between the perfectly acceptable example in (404) and the infelicitous, or at least marked, example in (407). If we maintain that the sentences are uttered at noon, the semantic difference is that the use of the modifier voor het college in (404) places the completion of k between noon and the course that will be given later in the afternoon, whereas the modifier na het collegeafter the course in (407) places it after the course (and thus also after speech time n).

| # | Ik | heb | vanmiddag | je artikel | na het college | gelezen. | |

| I | have | this.afternoon | my paper | after the course | read | ||

| 'This afternoon, I will have read your paper after the course.' | |||||||

That the future completion of k must be located between n and some point referred to by the adverbial phrase modifying k is even clearer when the modifier refers to a single point in time: the adverbial phrase om 3 uur in (408) refers to the latest time at which the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb must have been completed.

| Vanmiddag | heeft | het peloton | om 3 uur | de finish | bereikt. | ||

| this.afternoon | has | the peloton | at 3 o’clock | the finish | reached | ||

| 'The pack will reach the finish this afternoon at 3 oʼclock.' | |||||||

Similar restrictions do not occur if the completion of eventuality k precedes speech time n. If uttered at noon, the sentences in (409) are equally acceptable, despite the fact that the event time interval is only located between breakfast and speech time n in (409b).

| a. | Ik | heb | vanmorgen | je artikel | voor het ontbijt | gelezen. | |

| I | have | this.morning | your paper | before breakfast | read | ||

| 'This morning, I read your paper before breakfast.' | |||||||

| b. | Ik | heb | vanmorgen | je artikel | na het ontbijt | gelezen. | |

| I | have | this.morning | your paper | after breakfast | read | ||

| 'This morning, I read your paper after breakfast.' | |||||||

In past-perfect constructions such as (410), we seem to find exactly the same facts, although the judgments are a bit diffuse. When eventuality k is placed after n', it seems that the adverbial phrase must refer to some time after the completion of the event, as in (410a), which is as acceptable as its present-tense counterpart in (409a); example (410b) violates this restriction and is therefore marked and certainly less preferable to its present-tense counterpart in (409b).

| a. | Ik | had vanmorgen | je artikel | voor het ontbijt | gelezen. | |

| I | had this.morning | your paper | before breakfast | read | ||

| 'This morning, I had read your paper before breakfast.' | ||||||

| b. | ? | Ik | had vanmorgen | je artikel | na het ontbijt | gelezen. |

| I | had this.morning | your paper | after breakfast | read | ||

| 'This morning, I read your paper after breakfast.' | ||||||

That example (410b) is not as bad as one might expect may be due to the fact that vanmorgen can in principle also be read as a modifier of the past-tense interval. This is the case in the examples in (411), both of which are perfectly acceptable (provided that the adverbial phrase refers to an eventuality preceding n').

| a. | Ik | had gisteren | je artikel | voor het ontbijt | gelezen. | |

| I | had yesterday | your paper | before breakfast | read | ||

| 'Yesterday, I had read your paper before breakfast.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | had | gisteren | je artikel | na het ontbijt | gelezen. | |

| I | have | yesterday | your paper | after breakfast | read | ||

| 'Yesterday, I read your paper after breakfast.' | |||||||

Modification of the time interval j by a time adverbial referring to a time interval following n is not always successful in triggering a future reading in perfect-tense constructions. The examples in (412) show that Aktionsart can affect the result: atelic predicates like the state ziek zijnto be ill or the activity aan zijn dissertatie werkento work on his thesis usually resist a future interpretation.

| a. | Jan is | vorige week | ziek | geweest. | state | |

| Jan is | last week | ill | been | |||

| 'Jan was ill last week.' | ||||||

| a'. | $ | Jan is volgende week | ziek | geweest. |

| Jan is next week | ill | been |

| b. | Jan heeft | vanmorgen | aan zijn dissertatie | gewerkt. | activity | |

| Jan has | this.morning | on his dissertation | worked | |||

| 'Jan has worked on his PhD thesis all morning.' | ||||||

| b'. | $ | Jan heeft | morgen | aan zijn dissertatie | gewerkt. |

| Jan has | tomorrow | on his dissertation | worked |

The unacceptability of the primed examples seems to be related to the fact, discussed in Section 1.5.1, sub IB2, that the perfect has a different implication for eventuality k with telic and atelic predicates; we illustrate this difference again in (413) for activities and accomplishments.

| a. | Jan heeft | vanmorgen | aan zijn dissertatie | gewerkt. | =(412a); activity | |

| Jan has | this.morning | on his dissertation | worked | |||

| 'Jan has worked on his PhD thesis this morning.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan heeft | de brief | vanmorgen | geschreven. | accomplishment | |

| Jan has | the letter | this.morning | written | |||

| 'Jan has written the letter this morning.' | ||||||

Although the examples in (413) both present the eventualities expressed by the projection of the main verb as discrete, bounded units that are completed at or before speech time n, they differ with respect to whether the eventualities in question can be continued or resumed after n. This option seems natural for the activity in (413a): this example can easily be followed by ... en hij zal daar vanmiddag mee doorgaan... and he will continue doing so in the afternoon. The accomplishment in (413b), on the other hand, seems to imply that the eventuality has reached its implied endpoint (i.e. the letter is finished) and therefore cannot be continued after speech time n.

Atelic and telic predicates also differ with respect to modification by the accented adverb nunow, expressing that the state of completeness is reached at the very moment of speech; this use of nu is perfectly possible with telic predicates, whereas atelic predicates allow this use only if a durative adverbial phrase such as een uurfor an hour is added; cf. Janssen (1983) and the references cited there.

| a. | Jan heeft | nu | *(een uur) | aan zijn dissertatie | gewerkt. | activity | |

| Jan has | nu | one hour | on his dissertation | worked | |||

| 'Jan has worked on his PhD thesis for an hour ... now.' | |||||||

| b. | Jan heeft | de brief | nu | geschreven. | accomplishment | |

| Jan has | the letter | now | written | |||

| 'Jan has written the letter ... now.' | ||||||

Janssen suggests that this is because the moment at which atelic predicates can be considered “completed” is not salient enough to be pointed at by accented nunow; this can usually only be judged after some time has elapsed, unless the rightward boundary is explicitly indicated, e.g. by a durative adverbial phrase such as een uur. This unobtrusiveness of the endpoint of atelic eventualities is of course related to the fact that they can in principle be extended indefinitely; this is probably also the reason why speakers will refrain from using the perfect when it comes to future atelic eventualities; as in example (414a), the speaker will use the perfect only when the extent of the atelic predicate is explicitly bounded by a durative adverbial phrase.

| Morgen | heeft | Jan | ??(precies een jaar) | aan zijn dissertatie | gewerkt. | ||

| tomorrow | has | Jan | exactly one year | on his thesis | worked | ||

| 'Tomorrow Jan has worked on his thesis for a full year.' | |||||||

In other cases, the speaker will resort to the simple present in order to locate atelic eventualities in the non-actualized part of the present. This answers the question left open in Subsection II about the contrast in interpretation of the two examples in (402).

So far, we have tacitly assumed that the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb occurs only once. Although this may be the default interpretation, the examples in (416) show that this is not necessary: example (416a) expresses that in the actualized part of the present-tense interval i, denoted by vandaagtoday, the speaker has eaten three times before speech time n. Similarly, in (416b) the frequency adverb vaakoften expresses that within the actualized part of the tense interval i, denoted by the adverbial phrase dit jaarthis year, there have been many occurrences of the eventuality denoted by the phrase naar de bioscoop gaango to the movies.

| a. | Ik | heb | vandaag | drie maaltijden | gegeten: | ontbijt, | lunch en avondeten. | |

| I | have | today | three meals | eaten | breakfast | lunch and supper | ||

| 'I have eaten three times today: breakfast, lunch and supper.' | ||||||||

| b. | Ik | ben | dit jaar | vaak | naar de bioscoop | geweest. | |

| I | am | this year | often | to the cinema | been | ||

| 'I have often been to the movies this year.' | |||||||

As expected, the default interpretation of examples such as (416) is that the eventualities precede speech time n. However, this default reading can easily be overridden. An example such as Als ik vanavond naar bed ga, heb ik drie maaltijden gegeten: ontbijt, lunch en avondetenWhen I go to bed tonight, I will have eaten three meals: breakfast, lunch and supper can easily be uttered at dawn or at noon by someone with an eating disorder who wants to express his good intentions.

The fact that the present/past-tense interval can contain multiple occurrences of the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb is fully exploited in habitual constructions such as (417). These examples differ from the simple present examples in (385) in that they tend to locate the habit in the actualized part of the present-tense interval ia; for example, there is a strong tendency to interpret example (417b) to mean that Jan has quit smoking. However, it is certainly not necessary to interpret perfect habituals in this way, as can be seen from the fact that example (417a) can easily be followed by ... en hij zal dat wel blijven doen... and he will continue to do so.

| a. | Jan is | (altijd) | met de bus | naar zijn werk | gegaan. | |

| Jan has | always | with the bus | to his work | gone | ||

| 'Jan has (always) gone to his work by bus.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan heeft | (vroeger) | gerookt. | |

| Jan has | in.the.past | smoked | ||

| 'Jan has smoked in the past/used to be a smoker.' | ||||

Unlike their present-tense counterparts in (395), it does not seem possible to interpret the perfect-tense examples in (418) generically: the examples in (418a&b) are acceptable only if the subject refers to a (set of) unidentified true gent(s); example (418c) can at best lead to the interpretation that a certain whale has become a fish (which is an impossibility in our world).

| a. | # | Een echte heer | is hoffelijk | geweest. |

| a true gent | is courteous | been | ||

| 'A true gent has been courteous.' | ||||

| b. | # | Echte heren | zijn | hoffelijk | geweest. |

| true gents | are | courteous | been |

| c. | * | De walvis | is een zoogdier | geweest. |

| the whale | is a mammal | been |

Present-perfect clauses introduced by alswhen seem to allow both conditional and hypothetical readings, just like the simple-present examples in (387) from Section 1.5.4.1. The conditional reading illustrated in (419) is again the default. This example is ambiguous in that a teacher could say this sentence either to his students in general, to indicate that those who have fulfilled the condition expressed by the antecedent of the sentence may go, or to a particular student when he does not know whether that student has fulfilled the condition.

| Als | je | je spullen | op | geruimd | hebt, | mag | je | weg. | ||

| when | you | your things | away | cleared | has | be.allowed | you | go.away | ||

| Conditional reading 1: 'Anyone who has put away his things may go.' | ||||||||||

| Conditional reading 2: 'If you have put away your things, you may go.' | ||||||||||

The hypothetical reading of this sentence arises when the discourse participants know that the antecedent is not fulfilled in the actualized part of the present-tense interval, e.g. when the teacher addresses a particular student of whom he knows that he has not yet put his things away; cf. the gloss and rendering of (420).

| Als | je | je spullen | op | geruimd | hebt, | mag | je | weg. | ||

| as.soon.as | you | your things | away | cleared | has | be.allowed | you | go.away | ||

| hypothetical reading: 'As soon as you have put away your things, you may go.' | ||||||||||

The fact that contextual information is needed to distinguish between the two readings of the antecedent clause Als je je spullen opgeruimd hebt, mag je weg clearly shows that pragmatics is involved. However, it is possible to favor one reading by using an adverbial phrase. As in the corresponding present-tense examples, the conditional reading in (419) is favored by adding an adverb such as altijdalways to the consequence: Als je je spullen opgeruimd hebt, mag je altijd wegIf you have put away your things, you can always go. The same applies to the addition of alalready to the antecedent, since this locates the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb of the antecedent clause in the actualized part of the present-tense interval and thus blocks the hypothetical reading: Als je je spullen al opgeruimd hebt, mag je wegIf you have put your things away already, you can go. The addition of strakslater to the antecedent, on the other hand, favors the hypothetical reading, as it suggests that the speaker knows that the condition is not yet fulfilled at speech time: Als je straks je spullen opgeruimd hebt, mag je wegIf you have put your things away later, then you can go.

Past-perfect utterances allow both conditional and counterfactual readings, like the simple-past examples in (390) from Section 1.5.4.1. The default conditional reading can be found in (421a), which refers to some general rule that was valid in the relevant past-tense interval. The conditional reading is not easy to get when the pronoun je is interpreted referentially, as in (421b), which instead seems to prefer a counterfactual interpretation. This preference is again be pragmatic in nature; since the eventuality is located in the past-tense interval, the speaker and the addressee can be expected to know whether the addressee has fulfilled the condition mentioned in the antecedent.

| a. | Als | je | je spullen | op | geruimd | had, | mocht | je | weg. | |

| when | one | his things | away | cleared | had | be.allowed | one | go.away | ||

| Conditional: 'Anyone who had put away their things was allowed to go.' | ||||||||||

| b. | Als | je | je spullen | op | geruimd | had, | mocht | je | weg. | |

| when | you | your things | away | cleared | had | be.allowed | you | go.away | ||

| Counterfactual: 'If you had put away your things, you were allowed to go.' | ||||||||||

It is important to note that the use of the simple past of the verb mogento be allowed in the consequence does not necessarily imply that the leaving event denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb in the consequence is located before speech time n. In fact, the preferred interpretation of counterfactuals of the form in (421b) is that in possible worlds in which the condition mentioned in the antecedent is fulfilled, the leaving event would coincide with or follow speech time n. This will be clear from the fact that the use of the adverb gisterenyesterday is not possible in (422a). This again shows that the past-tense interval can include speech time n and thus overlap with the present-tense interval; cf. the discussion in Section 1.5.1, sub IC. For completeness’ sake, note that this restriction on adverbial modification is lifted when the consequence is in the perfect tense, as in (422b).

| Als | je | je spullen | op | geruimd | had, ... | ||

| when | you | your things | away | cleared | had | ||

| 'If you had put away your things, ...' | |||||||

| a. | ... | dan | mocht | je | nu/morgen/*gisteren | naar het feest. | |

| ... | then | be.allowed | you | now/tomorrow/yesterday | to the party | ||

| '... then you were allowed go to the party now/tomorrow.' | |||||||

| b. | ... | dan | had je | nu/morgen/gisteren | naar het feest | gemogen. | |

| ... | then | had you | now/tomorrow/yesterday | to the party | been.allowed | ||

| '... then you would have been allowed to go to the party now/tomorrow/yesterday.' | |||||||

An interesting fact about conditionals and hypotheticals is that the als-phrase alternates with constructions without als, in which the finite verb is in the first position of the clause: the antecedent in (422) can also take the form Had je je spullen opgeruimd, dan ... In the case of antecedent clauses of this form, counterfactuals are often used to express regret (“I wish I had put away...”) or a wish (“I wish I/he had put away ...”); for obvious reasons, the regret reading is more likely to occur when the counterfactual involves the speaker himself. For completeness, note that the consequences (here: dan had ik/hij weg gemogen) can easily be left implicit: cf. Had ik mijn spullen maar opgeruimd ...!

| a. | Had | ik | mijn spullen | maar | op | geruimd, | dan had ik | weg | gemogen. | ||

| had | I | my things | prt | away | cleared | then had I | away | been.allowed | |||

| 'If only I had put away my things, I would have been allowed to go.' | regret/wish | ||||||||||

| b. | Had | hij | zijn spullen | maar | op | geruimd, | dan had hij weg | gemogen. | ||

| had | he | his things | prt | away | cleared | then had he away | been.allowed | |||

| 'If only he had put away his things, he would have been allowed to go.' | wish | |||||||||

If the counterfactual involves the addressee, as in (424), the resulting structure is easily construed as a reproach. However, the construction is peculiar in that it is not possible to express the subject of the antecedent overtly, which strongly suggests that we are formally dealing with an imperative; cf. also the discussion of examples (177) and (178) in Section 1.4.2, sub I.

| a. | Had (*je) | je spullen | maar | op | geruimd, | (dan had je | weg | gemogen). | |

| had you | your things | prt | away | cleared | then had you | away | been.allowed | ||

| 'It is your own fault: if you had put away your things, you would have been allowed to go.' | |||||||||

| b. | Had | (*je) | niet | zo veel | gedronken | (dan | had | je | nu | geen kater). | |

| had | you | not | that much | drunk | then | had | you | now | no hangover | ||

| 'It would have been better if you had not drunk so much (then you would not have had a hangover now).' | |||||||||||

The counterfactual examples in this subsection all have in common that the speaker/hearer can be assumed to know whether the condition given in the antecedent is fulfilled (or not), which makes the conditional reading of these examples uninformative: the speaker could simply have given (or denied) the addressee permission to leave. The counterfactual reading, on the other hand, is informative because the speaker is informing the addressee about the situation that would have occurred if he had fulfilled the condition expressed by the antecedent; Grice’s maxim of quantity therefore favors this interpretation. This shows that this maxim is involved in triggering different kinds of irrealis meanings of past-perfect constructions.

Like the simple past in example (395), the past perfect in (425) can be used to express that the nominal description een echte heera true gent is not applicable to a specific person. Again, imagine the situation of a pregnant woman getting on a bus. All the seats are taken, and no one seems to be willing to oblige her by offering her a seat. An elderly lady gets angry and utters (425) to the boy next to her. Knowing that he had no intention of giving up his seat, she implies that the description een echte heer does not apply to him.

| Een echte heer | was nu | allang | opgestaan. | ||

| a true gent | was now | a.long.time.ago | up-stood | ||

| 'A true gent would have given up his seat a long time ago now.' | |||||

This section has shown that, as in the case of the simple tenses, the default reading of the perfect tenses is that the time interval j in which the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb must take place is identical to the complete present/past-tense interval i: the completion of the eventuality can take place before, during, or after speech time n/n'. In many cases, however, the interpretation is more restricted and can sometimes have non-temporal implications. This section has shown that this can easily be derived from the interaction between temporal information (tense and adverbial modification), modal information encoded in the sentence (the theory of possible worlds) and pragmatic information (Grice’s maxim of quantity).