- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Dutch has three universal quantifiers that can be used as modifiers: ieder/elkevery and alleall. These quantifiers are all universal in the sense that examples such as (187) express that the (contextually determined) set denoted by student is a subset of the set denoted by the VP een studentenkaart krijgento receive a student card.

| a. | Iedere/elke student | krijgt | een studentenkaart. | |

| every student | receives | a student.card |

| b. | Alle studenten | krijgen | een studentenkaart. | |

| all students | receive | a student.card |

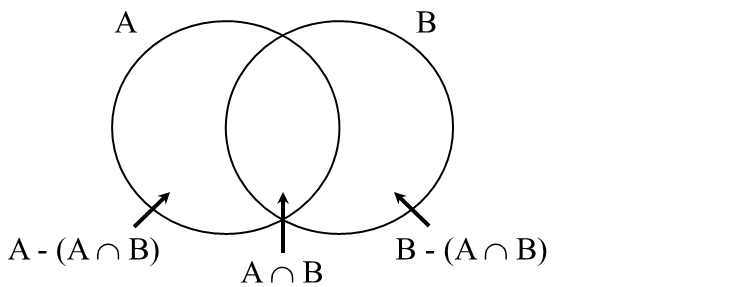

In terms of Figure 1, repeated here, this means that A - (A ∩ B) is empty.

The quantifiers ieder and elk in (187a) seem to be more or less free alternants, although Haeseryn et al. (1997:350) claims that speakers have a slight tendency to use ieder for [+human] nouns and elk for [-human] nouns, while Hoeksema (2013) denies this; we tend to agree with Hoeksema here. However, the following subsections will show that the quantifiers ieder and elk differ from the quantifier alle in (187b) in several other ways; cf. Kobele & Zimmermann (2012: §5.2.2) for a similar discussion of the German counterparts of these quantifiers.

Nouns containing the quantifiers ieder/elkevery and alleall can easily be used in virtually any common NP position; the examples in (188) show this for some argument positions of the verb and for nominal adverbial phrases. We will see that there are semantic differences which may affect their felicity in certain contexts, but their syntactic distribution is essentially the same.

| a. | Alle studenten | hebben | een lied | gezongen. | subject | |

| all students | have | a song | sung |

| a'. | Elke/iedere student | heeft | een lied | gezongen. | |

| every student | has | a song | sung |

| b. | Marie heeft | alle boeken over egels | gelezen. | direct object | |

| Marie has | all books over hedgehogs | read |

| b'. | Marie heeft ieder/elk boek over egels | gelezen. | |

| Marie has every book over hedgehogs | read |

| c. | Jan heeft | naar alle voorstellingen | gekeken. | PP-complement | |

| Jan has | to all performances | watched |

| c'. | Jan is naar iedere/elke voorstelling | gegaan. | |

| Jan is to every performance | been |

| d. | Jan komt | alle dagen | hier. | adverbial | |

| Jan comes | all days | here |

| d'. | Jan komt | elke/iedere dag | hier. | |

| Jan comes | every day | here |

The only exception seems to be complementive positions. This is illustrated here with the copular constructions in (189); while the use of a nominal predicate with alle is perfectly fine, a nominal predicate with ieder/elk is ruled out

| a. | Die vier meisjes | zijn | alle studenten die ik heb. | |

| those four girls | are | all students that I have |

| b. | * | Die vier meisjes | zijn | iedere/elke student die ik heb. |

| those four girls | are | every/each student that I have |

The claim that elk cannot be used in nominal predicates is contradicted in Hoeksema (2013), who points to examples such as (190a). However, there is reason to reject the claim that elke week is a nominal predicate here and to assume that we are actually dealing with a temporal adverbial phrase, as suggested by the fact that (190a) alternates with the virtually synonymous expletive construction in (190b). That elke week is a temporal adverbial and not a nominal predicate is clear from the fact that it is optional in (190b) and that it does not occur in the complementive position immediately preceding the clause-final verb in (190b).

| a. | Bridge | is elke week. | |

| bridge | is every week |

| b. | Er is elke week bridge. | |

| there is every week bridge | ||

| 'There is bridge every week.' |

| c. | dat | er | elke week | bridge is. | |

| that | there | every week | bridge is | ||

| 'that there is bridge every week.' | |||||

A conspicuous difference between the two types of modifiers in (187) is that noun phrases with ieder/elk are used with a singular head noun, while in the case of alle the head noun is plural. Correspondingly, subjects with ieder/elk trigger singular agreement on the finite verb, while noun phrases with alle trigger plural agreement. This is illustrated again by the examples in (191), which demonstrate the difference in grammatical number in yet another way: noun phrases with ieder/elk can only act as antecedents of singular pronouns such as zijnhis, while noun phrases with alle can only act as antecedents of plural pronouns such as huntheir. Note that (British) English uses their in both cases.

| a. | Iedere/elke student | moetsg | zijn/*hun opdracht | op tijd | inleveren. | |

| every student | must | his/their assignment | on time | hand.in | ||

| 'Every/Each student must hand in their assignment on time.' | ||||||

| b. | Alle studenten | moetenpl | hun/*zijn opdracht | op tijd | inleveren. | |

| all students | must | their/his assignment | on time | hand.in | ||

| 'All students must hand in their assignment on time.' | ||||||

The examples in (192) show that the difference in number is not a purely grammatical matter, but is also reflected in semantics; verbs like zich verzamelento gather or omsingelento surround require their subject to be plural or to refer to a group of entities, and such verbs can take a noun phrase modified by alle as their subject, but not a noun phrase modified by elk/ieder.

| a. | Alle studenten | moeten | zich | in de hal | verzamelen. | |

| all students | must | refl | in the hall | gather | ||

| 'All students must gather in the hall.' | ||||||

| a'. | * | Elke/Iedere student | moet | zich | in de hal | verzamelen. |

| every student | must | refl | in the hall | gather |

| b. | Alle soldaten | omsingelden | het gebouw. | |

| all soldiers | surrounded | the building |

| b'. | * | Elke/Iedere soldaat | omsingelde het gebouw. |

| every soldier | surrounded the building |

The acceptability of the noun phrases modified by alle is due to the fact that they allow a collective reading, i.e. they can refer to the (contextually determined) set of individuals denoted by the head noun as a whole; thus the subjects in the primeless examples in (192) express that the property denoted by the VP applies to the set denoted by student/soldaat as a whole. Noun phrases modified by elk/ieder, on the other hand, have a distributive reading: a noun phrase such as iedere/elke student expresses that the property denoted by the VP applies to each entity in the set individually.

The examples in (192) above have shown that noun phrases modified by elk/ieder have a distributive reading, while noun phrases modified by alle can have a collective reading. Note, however, that alle is also compatible with a distributive reading: this is actually the preferred reading of example (193a), which makes it more or less semantically equivalent to (193b).

| a. | Alle boeken | kosten | € 25. | |

| all books | cost | € 25 |

| b. | Elk/Ieder boek | kost | €25. | |

| every book | costs | €25 |

We see the ambiguity of noun phrases with alle between a collective and a distributive reading again in (194a). In its distributive reading, this example is semantically equivalent to (194b); the two sentences express that the activity of singing a song applies to each student individually; the meaning of these sentences can be satisfactorily represented by a universal operator: ∀x [Student(x) → Has sung (x, a song)]. The collective reading of (194a), on the other hand, expresses that the students sang a certain song as a group, a reading that is not available for (194b). For this collective reading of alle, the semantic representation with a universal operator seems inappropriate: strictly speaking, therefore, it is somewhat misleading to use the term universal quantifier in the case of this collective use of alle.

| a. | Alle studenten | hebben | een lied | gezongen. | |

| all students | have | a song | sung |

| b. | Elke/iedere student | heeft | een lied | gezongen. | |

| every student | has | a song | sung |

Example (195a) shows that the collective reading of alle studenten can be forced by adding a modifier of the type met elkaartogether or samentogether. That these modifiers force a collective reading is clear from the fact, illustrated in (195b), that they are incompatible with the distributive quantifiers ieder and elk.

| a. | Alle studenten | hebben | met elkaar/samen | een lied | gezongen. | |

| all students | have | with each/together | a song | sung | ||

| 'All students have sung a song together.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Elke/iedere student | heeft | met elkaar/samen | een lied | gezongen. |

| every student | has | with each/together | a song | sung |

The ambiguity of noun phrases with alle between a collective and a distributive reading is probably responsible for the fact that they can be used as nominal predicates, whereas noun phrases with (distributive) elk/ieder do not allow this use; cf. the examples in (189) from Subsection A.

Another difference between the two types of universal quantifier comes to the fore in noun phrases with an ordinal numeral. An example such as (196a) is perfectly acceptable, and expresses that the 100th, 200th, etc. visitor will receive a present. Example (196b), on the other hand, yields to a virtually uninterpretable result.

| a. | Iedere/elke honderdste bezoeker | krijgt | een cadeautje. | |

| every/each hundredth visitor | receives | a present | ||

| 'Every hundredth visitor gets a present.' | ||||

| b. | *? | Alle honderdste bezoekers | krijgen | een cadeautje. |

| all hundredth visitors | receive | a present |

In noun phrases with a cardinal numeral, the use of the quantifiers ieder and elk leads to a somewhat marked result with a special interpretation: example (197a) seems to divide the set of visitors into groups of ten persons each. The use of the quantifier alle in example (197b), on the other hand, is perfectly acceptable in a context in which the cardinality of the set of visitors is 10; the quantifier alle then emphasizes that the property denoted by the VP een cadeautje krijgento get a present applies to all entities in this set. Section 19.2.1, sub V, has already shown that the quantifier and the numeral constitute a phrase; the primed (b)-examples show that this phrase can also be used as a complex predeterminer (cf. Section 20.1.2.2) or as a floating quantifier (cf. Subsection III).

| a. | ? | Iedere/elke tien bezoekers | krijgen | een cadeautje. |

| every ten visitors | receive | a present |

| b. | Alle tien | bezoekers | krijgen | een cadeautje. | |

| all ten | visitors | receive | a present |

| b'. | Alle | tien | de bezoekers | krijgen | een cadeautje. | |

| all | ten | the visitors | receive | a present |

| b''. | De | bezoekers | krijgen | alle tien | een cadeautje. | |

| the | visitors | receive | all ten | a present |

The universal quantifiers elke/iedere and alle are not only used to quantify over sets of entities that are part of domain D, but they can also be used in generic statements, expressing a general rule that is assumed to be true in the speaker’s conception of the universe. As discussed in Section 18.1.1.5, we should distinguish the three types of generic statements in (198). Here we will discuss only the first two types.

| a. | De zebra | is gestreept. | |

| the zebra | is striped |

| b. | Een zebra | is gestreept. | |

| a zebra | is striped |

| c. | Zebra’s | zijn gestreept. | |

| zebras | are striped |

When a generic statement contains a definite noun phrase, the generic statement applies generally to (entities belonging to) a particular species. Example (199a) refers to a certain species of birds, and it is claimed that this species has become extinct. In this case, the definite article cannot be replaced by the universal quantifiers alle and elke/iedere.

| a. | De Dodo | is uitgestorven. | |

| the Dodo | is extinct |

| b. | # | Alle Dodo’s | zijn | uitgestorven. |

| all Dodos | are | extinct |

| c. | * | Elke/Iedere dodo | is uitgestorven. |

| every dodo | is extinct |

However, the universal quantifier alle would be acceptable in a situation where the noun denotes a species that can be divided into several subspecies: in such a case, alle would quantify over all subspecies; elk and ieder would still yield unacceptable results in such a case. The examples in (200) are intended to illustrate this.

| a. | De Dinosaurus | is uitgestorven. | |

| the Dinosaur | is extinct |

| b. | Alle Dinosaurussen | zijn | uitgestorven. | |

| all Dinosaurs | are | extinct |

| c. | * | Elke/Iedere dinosaurus | is uitgestorven. |

| every dinosaur | is extinct |

When a generic statement contains an indefinite noun phrase, the generic statement generally applies to a prototypical member of the set denoted by the head noun. Example (201a) asserts that the prototypical zebra is striped. In this case, the indefinite article can easily be replaced by the universal quantifier alle: example (201b) simply asserts that the property of being striped applies to all zebras. The quantifiers ieder and elk can also be used in this context, but in this case the sentence has an emphatic flavor and is pronounced with the accent on the quantifier: example (201c) is best interpreted as saying that each and every entity that is a zebra is striped (cf. Haeseryn et al. 1997:349).

| a. | Een zebra | is gestreept. | |

| a zebra | is striped |

| b. | Alle zebra’s | zijn gestreept. | |

| all zebras | are striped |

| c. | (?) | Iedere/Elke zebra | is gestreept. |

| every zebra | is striped |

The grammatical gender feature [±neuter] may also serve to distinguish elk/ieder form alle, in that the form of elk/ieder depends on the value of this gender feature of the head noun, while the form of alle is invariant. This difference may be related to the fact that the head noun is singular in the former case, but plural in the latter: gender agreement between a modifier and a singular head noun is common, while the form of the modifier of a plural noun is insensitive to the gender of the noun; cf. Section 16.2, sub I.

| a. | iedere/elke | man | non-neuter: de man | |

| every/each | man |

| a'. | ieder/elk | kind | neuter: het kind | |

| every/each | child |

| b. | alle | mannen/kinderen | |

| all | men/children |

The examples in (203) show that the de-nouns mensperson and persoonperson are exceptional in that they do not accept/need the inflectional -e ending; it is claimed that the use of elk/ieder mens is preferred by Dutch speakers while Flemish speakers prefer elke/iedere mens; cf. taaladvies.net/elk-of-elke-mens/. It seems that Dutch speakers allow both the bare and the inflected form with persoon. Note that the acceptability of the bare forms may be related to the fact that persoon (and possibly also mens) are grammatical nouns in the sense of Emonds (1985; 2000); cf. Section 19.1.1.6, sub IIIC2.

| a. | elk(e)/ieder(e) | mens | |

| every/each | person |

| b. | elk(e)/ieder(e) | persoon | |

| every/each | person |

A final difference between elk/ieder and alle concerns non-count nouns. Since universal quantifiers typically quantify over a set of discrete entities, they are not expected to combine with non-count nouns. As shown in (204) for abstract non-count nouns, this expectation is indeed borne out for elke/ieder, but not for alle, which can be combined with such non-count nouns. It seems reasonable to relate this difference to the fact that only alle can give rise to a collective reading, which in the case of non-count nouns results in a “total-quantity” reading.

| a. | * | Elke/iedere | ellende | is ongewenst. |

| every | misery | is unwanted |

| b. | Alle ellende | is voorbij. | |

| all misery | is passed | ||

| 'All misery has passed.' | |||

This does not mean that elk/ieder can never be combined with a non-count noun, but if it is, there will be a semantic clash between the distributive reading of elk/ieder and that of the non-count noun, resulting in a reinterpretation of the non-count noun as a count noun. For example, the noun phrase with the substance noun wijn in (205a) usually refers to a contextually determined quantity of wine. In (205b), on the other hand, elk/ieder triggers a count-noun interpretation of this noun, which now means “type of wine”.

| a. | De wijn | wordt | gekeurd. | |

| the wine | is | sampled |

| b. | Elke/iedere wijn | wordt | gekeurd. | |

| every wine | is | sampled |

The quantifier alle allows both the non-count and the count-noun interpretation: the noun wijn appears in the singular in the first case and in the plural in the second, as shown in the examples in (206).

| a. | Alle wijn | wordt | gekeurd. | |

| all wine | is | sampled |

| b. | Alle wijnen | worden | gekeurd. | |

| all wines | are | sampled |

The claim that elk/ieder can only be used with count nouns is contradicted in Hoeksema (2013) by pointing to example (207a); however, the presupposition that grond is a non-count noun is clearly wrong in view of (207b). The other counterexample to this claim is Jan laat elke hoop varenJan gives up all hope, which is clearly idiomatic in nature and actually more common with alle, and should therefore be seen as not belonging to the core grammar. In short, the claim remains unchallenged.

| a. | De aantijgingen | missen elke grond. | |

| the allegations | lack every ground | ||

| 'The allegations lack any foundation.' | |||

| b. | Er | zijn | goede gronden | [om | dit | te verwerpen]. | |

| there | are | good grounds | comp | this | to reject | ||

| 'There are good grounds for rejecting this.' | |||||||

When a universal quantifier is used as an argument, it is usually realized as the [+human] quantified pronoun iedereeneveryone or as the [-human] quantified pronoun alleseverything in (208); cf. Section 18.2. Elkeeneveryone also occurs in formal language, but is considered archaic/obsolete.

| a. | Iedereen | ging | naar | de vergaderzaal. | |

| everyone | went | to | the meeting.hall |

| b. | Alles | is uitverkocht. | |

| everything | is sold.out |

The quantifier alle(n) in (209) can serve the same function as the quantifiers iedereen/alles in (208) if the context provides sufficient information about the intended referent set; it is then possible to use alle(n) as a pronominal quantifier instead of the complete quantified noun phrases alle studenten/boekenall students/books. The independent use of alle to refer to inanimate entities is characteristic of more formal language; to a lesser extent, the same holds for allen to refer to humans (or animals).

| a. | Alle studenten/Allen | gingen | naar | de vergaderzaal. | |

| all students/all | went | to | the meeting.hall |

| b. | Alle boeken/Alle | zijn | uitverkocht. | |

| all books/all | are | sold.out |

Let us adopt our earlier assumption from Section 19.1.1.6, sub IIIC2 that the plural quantifier allen arises thanks to the presence of the silent noun persoon. If so, the subjects in (209a) can be given the structural representations in (210), and allen arises as a result of the merging of the quantifier and the plural ending of persoon in the post-syntactic component.

| a. | [DP Ø [NumP | [alle number] [Numplural [NP studenten]]]]] |

| b. | [DP Ø [NumP | [alle number] [Numplural [NP persoon-en]]]]] |

Note that this analysis can also account for the fact that inflected quantifiers can only be understood as “consistently human”: conjunctions that are not consistently human, like mannen en hun auto’smen and their cars, take alle, not allen, as their independent quantifier.

It is also possible to use the modifiers ieder and elk as arguments, although this is considered very formal. The independent use of these quantifiers seems more or less restricted to contexts in which they are modified by a postnominal van-PP with a plural pronoun/noun phrase as complement, as in (211). Note that there is a tendency to use ieder for [+human] referents; the use of elk for [+human] entities seems to lead to a degraded result (although it does occur on the internet).

| a. | Ieder/?Elk van ons | weet | dat | de voorzitter | geroyeerd | is. | |

| each of us | knows | that | the chair | expelled | is | ||

| 'Each of us knows that the chair has been expelled.' | |||||||

| b. | Elk/??Ieder van die boeken | is een fortuin | waard. | |

| each of those books | is a fortune | worth | ||

| 'Each of those books is worth a fortune.' | ||||

However, there are some idiomatic examples where ieder is used independently without a modifier, as in ieder zijn deeleveryone will get his share. Furthermore, ieder can be used independently without a modifier when it heads an indefinite noun phrase introduced by the article een (usually written as a single word); this seems less acceptable or obsolete with elk.

| Een | ieder/??elk | weet | dat | de voorzitter | geroyeerd | is. | ||

| an | each | knows | that | the chair | expelled | is | ||

| 'Everyone knows that the chair has been expelled.' | ||||||||

Floating quantifiers are quantifiers that are associated with noun phrases that occur elsewhere in their minimal clause, but with which they do not form a syntactic constituent. This use, which is restricted to universal quantifiers, is illustrated in (213a&b); the floating quantifier allenall is quite formal and alternates with the more colloquial form allemaal. Example (213c) shows that the combinations of alle and a cardinal numeral (here: alle tien) can also be used as floating quantifiers.

| a. | De studenten | kregen | ieder/elk | honderd euro. | |

| the students | got | each | hundred euro | ||

| 'The students got a hundred euros each.' | |||||

| b. | De studenten | kregen | allemaal/(?)allen | honderd euro. | |

| the students | got | all | hundred euro | ||

| 'All the students got a hundred euros.' | |||||

| c. | De studenten | kregen | alle tien | honderd euro. | |

| the students | got | all ten | hundred euro | ||

| 'All ten students got a hundred euros.' | |||||

In this usage, the difference between ieder/elk and allen again seems to be that the former must have a distributive reading, while the latter has a more collective flavor. It is difficult to demonstrate this with the examples in (213), since (213b) cannot be used to express that the students received a hundred euros as a group, but our impression seems to be supported by the examples in (214). Since the predicate bij elkaar komen requires a plural/collective subject, we can explain the contrast between the two examples by appealing to the fact that the quantifiers ieder and elk force a distributive reading of the subject, while alle(maal) also allows a collective reading; the same holds for the combination alle and a cardinal.

| a. | * | De studenten | kwamen | ieder/elk | bij elkaar. |

| the students | came | each | together |

| b. | De studenten | kwamen | allemaal/(?)allen | bij elkaar. | |

| the students | came | all | together |

The use of floating quantifiers with [-human] antecedents seems to be more restricted than with [+human] antecedents. The use of the distributive quantifiers in (215a) seems to lead to degraded results, although they are accepted by some speakers (and occasional instantiations can be found on the internet); cf. Hoeksema (2013). In (215b), allemaal is clearly preferred to alle, unless the latter is combined with a cardinal.

| a. | % | De vliegtuigen | worden | elk/ieder | gekeurd. |

| the airplanes | are | each | tested |

| b. | De vliegtuigen | worden | allemaal/alle ?(tien) | gekeurd. | |

| the airplanes | are | all/all ten | tested |

With an interrogative antecedent, only the floating quantifier allemaal seems possible: elk/ieder and alle(n) all give rise to a degraded result. In (216), we give examples with a [+human] antecedent.

| a. | * | Wie/??welke studenten | kregen | er | elk/ieder | honderd euro? |

| who/which students | got | there | each | hundred euro |

| b. | Wie/welke studenten | kregen | er | allemaal/*allen | honderd euro? | |

| who/which students | got | there | all | hundred euro |

We will not go any deeper into the properties of these floating quantifiers here. A more general discussion of floating quantifiers can be found in Section 20.1.4, sub III.