- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

The postverbal field differs from the clause-initial position in that it does not consist of a unique, single position: it can easily contain more than one constituent of the clause. This is illustrated by the examples in (47), taken from Koster (1974); in (47a) all constituents precede the clause-final verb, in (47b&c) the verb is followed by a single constituent, while in (47d) it is followed by two constituents. The examples in (47) also show that the phrases in the postverbal field can be of different types: the PP aan zijn vader is a PP-complement of the verb, while the PP tijdens de pauze is an adverbial modifier of time. However, it is not the case that all arguments and adverbial phrases can be placed in the postverbal field; one of the aims of this section is to establish a number of restrictions on this option.

| a. | dat | Jan tijdens de pauze | aan zijn vader | dacht. | |

| that | Jan during the break | of his father | thought | ||

| 'that Jan was thinking of his father during the break.' | |||||

| b. | dat Jan tijdens de pauze dacht aan zijn vader. |

| c. | dat Jan aan zijn vader dacht tijdens de pauze. |

| d. | dat Jan dacht aan zijn vader tijdens de pauze. |

The discussion in this section is organized as follows. Subsection I begins with a discussion of the placement of the arguments of the verb, showing that their ability to occur in the postverbal field depends on their categorial status: in general, nominal complements precede, complement clauses follow, and PP-complements can either precede or follow the clause-final verbs. Subsection II discusses the restrictions on the distribution of adverbial phrases; it will be shown that most types of adverbial phrases can occur either before or after the clause-final verbs, with the notable exception of manner adverbs, which must precede the clause-final verbs. Subsection III will show that the postverbal field can contain not only complete clausal constituents, but also subparts of such constituents, e.g. relative clauses or PP-modifiers of nominal arguments.

The examples in (48a&b) show that nominal arguments differ from clausal arguments in that the former usually precede the clause-final verbs, while the latter follow them. PP-complements differ from nominal and clausal arguments in that they can either precede or follow the clause-final verbs.

| a. | dat | Jan hem | <het verhaal> | vertelde <*het verhaal>. | nominal compl. | |

| that | Jan him | the story | told | |||

| 'that Jan told him the story.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan hem | <*dat zij komt> | vertelde <dat zij komt>. | clausal compl. | |

| that | Jan him | that she comes | told | |||

| 'that Jan told him that she will come.' | ||||||

| c. | dat | Jan hem | <over haar komst> | vertelde <over haar komst>. | PP-compl. | |

| that | Jan him | about her arrival | told | |||

| 'that Jan told him about her arrival.' | ||||||

Subsection A first discusses the contrast between nominal and clausal complements while Subsection B continues with a discussion of the placement of PP-complements. Subsection C is comparative and more theoretical in nature; it will briefly consider the placement of the same types of arguments in English in order to show that our findings for Dutch may reflect a more general property of the Germanic languages.

The differences in the placement of nominal and clausal complements relative to the clause-final verbs shown in (48a&b) have been a focus of attention since the rise of early generative grammar. The assumption that direct objects are inserted in the complement position of the verb inevitably led to the conclusion that the alternate placement of direct objects in the sentence is the result of some movement transformation. Thus, the question arose as to which is the base position of the direct object: that of the nominal complement in (48a) or that of the clausal complement in (48b)? The consensus on this question in the mid-1970s seemed to be that Dutch is underlyingly an OV-language, and that objects must therefore uniformly be base-generated in preverbal position; examples such as (48b) are thus derived by an obligatory extraposition rule, which moves the clause from the preverbal object position to some postverbal position; cf. Koster (1973/1974/1975).

Although the extraposition approach remained dominant until the mid-1990s, it was clear from the beginning that it was not without problems; cf. De Haan (1979). The most conspicuous problem had to do with freezing: since extraposition is movement, and movement usually produces a freezing effect, the extraposition approach predicts that clausal complements are islands for extraction; however, the fact that wh-movement takes place from the postverbal embedded clause in example (49) shows that this prediction is false. Recall from Section 9.3, sub I, that the intermediate trace t'i is due to the fact that long wh-movement takes place via an escape hatch in CP.

| Welk boeki | heeft | Jan gezegd [t'i | dat | mijn zuster ti | gelezen | heeft]? | ||

| which book | has | Jan said | comp | my sister | read | has | ||

| 'Which book has Jan said that my sister has read?' | ||||||||

One way to save the assumption that Dutch is underlyingly an OV-language and thus requires the direct object to be base-generated in preverbal position would be to assume that the postverbal clause is actually not the true object of the verb, but that it is a dependent of a phonetically empty anticipatory pronoun comparable to het in (50a), where the indices indicate the relation between the pronoun and the clause. The (empty) pronoun would then be the true object of the verb; cf. Koster (1999). However, this analysis is generally rejected because (50b) shows that the presence of an overt anticipatory pronoun normally blocks wh-movement from the embedded clause; cf. Hoekstra (1983), Bennis (1986), and many others. Note that we have included the particle nog in these examples because some speakers seem to prefer some material between the anticipatory pronoun and the clause-final verb.

| a. | dat | Jan | heti | (nog) | zei | [dat mijn zuster | dat boek | gelezen | heeft]i. | |

| that | Jan | it | prt | said | that my sister | that book | read | has | ||

| 'that Jan said it that my sister has read that book.' | ||||||||||

| b. | * | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan heti | (nog) | gezegd | [dat | mijn zuster ti | gelezen | heeft]i? |

| which book | has | Jan it | prt | said | that | my sister | read | has | ||

| Intended reading: 'Which book has Jan said that my sister has read?' | ||||||||||

If we want to maintain that nominal and clausal objects are base-generated in the same position, the obvious alternative to explore is to assume that they are both base-generated in postverbal position, and that the nominal object is moved to some preverbal position. This approach has become popular since Kayne (1994), where it was argued that rightward movement is excluded on general grounds, so that movement is uniformly to the left. One virtue of this approach is that we know independently that noun phrases can be moved to higher/more leftward positions; for example, it is commonly assumed that the subject of a passive clause is (or at least can be) moved from the position occupied by the direct object of the corresponding active clause into the regular subject position of the clause, as in (51b), in order to obtain nominative case and/or to establish agreement with the finite verb.

| a. | dat | Jan Marie | het boek | aanbood. | active | |

| that | Jan Marie | the book | prt.-offered | |||

| 'that Jan offered Marie the book.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | het boeki | Marie ti | aangeboden | werd. | passive | |

| that | the book | Marie | prt.-offered | was | |||

| 'that the book was offered to Marie.' | |||||||

In line with this tack, we might assume that the nominal object also moves from its underlying postverbal position to some higher position where it can be assigned accusative case or establish abstract (i.e. phonetically invisible) object-verb agreement (which is morphologically expressed in many other languages). A possible problem with this proposal is that it incorrectly predicts freezing of the nominal direct object; example (52a) shows that the phrase wat voor een boekwhat kind of book functions as a single nominal phrase, which strongly suggests that (52b) is derived by extracting the element wat from this complex phrase, and thus that nominal objects are not islands for wh-extraction.

| a. | [Wat voor een boek]i | heeft | mijn zuster ti | gelezen. | |

| what kind of book | has | my sister | read | ||

| 'What kind of book did my sister read?' | |||||

| b. | Wati heeft mijn zuster [ti voor een boek] gelezen. |

The discussion above shows that we can only maintain the assumption that nominal and clausal complements are base-generated in the same position if we assume that certain obligatory movement operations do not result in freezing; cf. Broekhuis (2008) for a proposal to this effect. However, it may also be the case that the presupposition that nominal and clausal complements are base-generated in the same position is incorrect, and that they are simply base-generated in a preverbal or postverbal position, respectively, as proposed in De Haan (1979:44) and Barbiers (2000) for Dutch, and in Haider (2000) for German. A possible problem with this solution is that the verb and the postverbal clause form a base-generated constituent, which leads to the false prediction that postverbal clauses must precede extraposed PPs: this means that extraposition of the PP tegen Peterto Peter in (53a) should lead to the order in (53b), whereas the order in (53b') is actually much preferred.

| a. | dat | Jan | tegen Peter | [zei | [dat | hij | zou | komen]]. | |

| that | Jan | to Peter | said | that | he | would | come | ||

| 'that Jan said to Peter that he would come.' | |||||||||

| b. | ?? | dat | Jan | [zei | [dat | hij | zou | komen]] | tegen Peter. |

| that | Jan | said | that | he | would | come | to Peter |

| b'. | dat | Jan | zei | tegen Peter | [dat | hij | zou | komen]. | |

| that | Jan | said | to Peter | that | he | would | come |

This subsection has briefly discussed three approaches to the placement of nominal and clausal arguments: two movement approaches (one involving rightward movement of clausal and one involving leftward movement of nominal arguments) and one base-generation approach. We have seen that they all run into various possible problems for which special provisions should be made.

Subsection A has shown that nominal and clausal complements are strictly ordered with respect to the clause-final verbs. This does not hold for PP-complements, which can normally occur either to the left or to the right of these verbs.

| a. | dat | Jan | <over het probleem> | nadacht < over het probleem >. | |

| that | Jan | about the problem | prt.-thought | ||

| 'that Jan was thinking about the problem.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Jan | <op het telefoontje> | wacht <op het telefoontje >. | |

| that | Jan | for the phone.call | waits | ||

| 'that Jan is waiting for the phone call.' | |||||

In such cases, it seems easy to determine the base position of the PP: assuming that the two positions are related by movement, we predict that the PP in the derived position will exhibit a freezing effect. The fact, illustrated by the examples in (55), that R-extraction is possible from the preverbal but not from the postverbal PP thus leads to the conclusion that the preverbal position is the more basic one; cf. Koster (1978: §2.6.4.4), Corver (2006b/2017) and Ruys (2008). This can be taken as support for an underlying OV-order in Dutch, assuming that PP-complements are base-generated in the complement position of the verb.

| a. | dat | Jan er | de hele dag | <aan> | dacht <*aan> | |

| that | Jan there | the whole day | about | thought | ||

| 'that Jan was thinking about it all day.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan er | de hele dag | <op> | wacht <*op> | |

| that | Jan there | the whole day | for | waits | ||

| 'that Jan was waiting for it all day.' | ||||||

The conclusion that the postverbal placement of PP-complements is the result of an extraposition operation, which has become known as PP-over-V, seems almost inescapable if one assumes that movement invariably produces a freezing effect. However, there are also serious problems with the claim that the stranded prepositions in (55) occupy the complement position of the verb. First consider example (56a), which shows that so-called VP-topicalization involves movement of a larger verb phrase that may include at least the direct object, i.e. the complement position of the main verb. The earlier conclusion that stranded prepositions must occupy the base position of the PP-complement thus implies that they are VP-internal and consequently must be pied-piped by VP-topicalization. However, the (b)-examples in (56) show that the stranded must be stranded; pied piping leads to a severely degraded result; cf. Den Besten & Webelhuth (1990).

| a. | [VP | Dat boek lezen]i | wil | Jan | niet ti. | |

| [VP | that book read | wants | Jan | not | ||

| 'Jan does not want to read that book.' | ||||||

| b. | [VP | wachten]i | wil | Jan er | niet | op ti. | |

| [VP | wait | wants | Jan there | not | for |

| b'. | * | [VP | op | wachten]i | wil | Jan er | niet ti. |

| * | [VP | for | wait | want | Jan there | not |

If we accept the freezing effect as a diagnostic for movement, the acceptability of (56b) suggests that PP-complements are not base-generated as a complement of the verb at all, but VP-externally. Analyses of this kind have indeed been proposed on independent grounds and amount to saying that extraposition of PPs does not result from rightward movement of the PP but from an (optional) leftward movement of the VP into a position left-adjacent of the PP, as in (57). An early proposal of this kind can be found in Barbiers (1995a), where it is claimed that the landing site of the VP is the specifier of the PP, and that this turns the PP into an island for extraction; this account for the fact, illustrated in (55), that R-extraction is only possible when the PP precedes the verb.

| a. | ... PP [... VP] ⇒ ... [VPi [PP [... ti ]]] |

A possible problem for (57) is that PP-complements are not generated within the lexical projection of the verb, but this can be solved if we follow Kayne (2004), which claims that PP-complements of verbs are not inserted as a unit but derived in the course of the derivation; the preposition is inserted as a functional head, which attracts a nominal complement of the verb. After this, the VP can be moved into the specifier of the PP. The (simplified) derivation is given in (58).

| a. | ... P [... [VP V DP]] ⇒ |

| b. | ... P+DPi [... [VP V ti ]] ⇒ |

| c. | ... [PP [VP V ti ]j [P+DPi [...tj ]]] |

The proposals in (57) and (58) have given rise to a rich research program; cf. Den Dikken (1995) for an attempt to describe the extraposition of clauses discussed above in terms of leftward VP-movement, and Kayne (2000: Part III) and later work for similar attempts to explain a wide range of seemingly rightward movement phenomena in these terms. Because of the highly technical nature of these proposals, we will not discuss them, but mention them here as evidence for the claim that it is not a priori obvious whether PP-complements are base-generated to the left or to the right of clause-final verbs and, even more surprisingly, that it is not even obvious that they are base-generated in the complement position of the verb.

The early extraposition approach considers the clause-final verbs as the pivot around which a number of syntactic processes take place. Complements are inserted in preverbal position and various category-specific movement rules lead to a reordering of the verb and its complements. Such rearrangements are excluded for nominal complements, obligatory for clausal complements, and optional for PP-complements. The central role ascribed to the verb is aptly captured by the term PP-over-V in the case of extraposition of PPs. Later research has shown, however, that the pivotal role of verbs may be an accidental property of Dutch and German (i.e. the Germanic OV-languages). This can be illustrated by the English examples in (59).

| a. | that John told the story yesterday. |

| b. | * | that John told yesterday the story. |

| b'. | * | that John said that he will come yesterday. |

| b''. | that John said yesterday that he will come. |

| c. | that John waited for his father a long time. |

| c'. | that John waited a long time for his father. |

Despite the fact that nominal, clausal and prepositional complements all follow the main verb in English, it is clear that they exhibit a distributional difference similar to the corresponding elements in Dutch. The fact that clausal complements must follow time adverbs such as yesterday, whereas nominal complements usually precede such adverbs, shows that these complements occupy different positions. The fact that the PP-complement can either precede or follow the adverbial phrase a long time reflects the distributional behavior of the Dutch PP. The correspondence between the Dutch and English examples shows that it is not so much the position of the complements relative to the verb that is at stake here, but rather their absolute position; in both Dutch and English, the three types of complements simply occupy different positions in the clause. The hypothesis would therefore be that Dutch and English behave identically when it comes to the placement of the complements of the verb, but differently when it comes to the placement of the verb itself. One implementation, which seems to be widely accepted by the current generation of generative grammarians, is the claim that the lexical domain of the clause is not just a simple projection of the verb V, as suggested by the representation in (10), repeated here as (60a), but consists of at least two projections: one headed by a root element, usually (somewhat misleadingly) represented by V, and another headed by a so-called light verb v, as indicated in (60b); cf. Chomsky (1995). Recall that X in this structure stands for an unspecified number of functional heads that may be needed to provide a complete description of the structure of the clause.

| a. | [CP ... C [TP ... T [XP ... X [VP ... V ...]]]] |

| b. | [CP ... C [TP ... T [XP ... X [vP ... v [VP ... V ...]]]]] |

The basic intuition behind the structure in (60b) is that all verbs are in fact derived from some nonverbal root by affixation with the verbal morpheme v. Although the Dutch light verb v is usually phonetically empty, this hypothesis is empirically supported by Latinate verbs such as irriterento irritate: this verb can be taken to be derived from a nonverbal root irrit-, which can also be used as input for the adjective irritant or the noun irritatie. The Dutch light verb v can thus be seen as a zero morpheme comparable to -eren in (61a).

| a. | [[irrit‑]stem -eren V] ‘to irritate’ |

| b. | [[irrit‑]stem -antA] ‘irritating’ |

| c. | [[irrit‑]stem -atieN] ‘irritation’ |

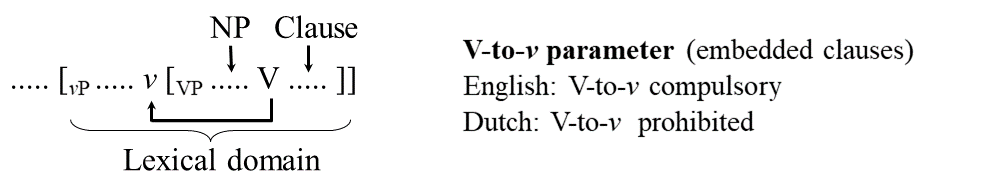

The correspondences between Dutch and English can now be explained by assuming that in these languages nominal, clausal and prepositional complements occupy the same surface positions in the clause, while the differences can be explained by assuming that the root V moves to (merges with) the light verb v in English but not in Dutch embedded clauses. This is shown for nominal and clausal complements in (62). The presumed difference in V-to-v movement between English and Dutch can in fact be held responsible for the fact that English emerges as a VO-language, while Dutch emerges as an OV-language; cf. Broekhuis (2008/2011/2023) and Barbiers (2000) for more detailed discussion.

|

Note that the schematic representation in (62) is not intended to make any claim about the base positions of nominal and clausal complements; it may well be that VP is actually a larger constituent within which the nominal or clausal complement has moved to its surface position; cf. Johnson (1991), Koizumi (1993), and Broekhuis (2008) for leftward movement of nominal objects within this VP-domain.

This subsection has briefly discussed the distribution of postverbal arguments: nominal and clausal arguments occur pre and postverbally, respectively, while PP-complements can occur on either side of the clause-final verbs. Starting from the claim that complements are all base-generated in the complement position of the verb, generative grammar has attempted to account for the different placement options by means of specific rearrangements in the clause. Early proposals included obligatory extraposition of clausal arguments and optional PP-over-V. Since the mid-1990s, proposals have been developed that involve leftward movement of nominal complements and verbal projections. And there are also proposals that simply reject the claim that nominal and clausal arguments are base-generated in the same position. The debate over the derivation of extant surface orders is ongoing and far from settled, and this subsection has reviewed only a small number of empirical facts that have played a crucial role in motivating/testing the various proposals. A more detailed description of the data can be found in Section 12.1.

It is often claimed that the postverbal field can contain not only prepositional and clausal complements of the verb, but also various types of adverbial phrases (but see Section 12.3, which will show that this claim is controversial and may need to be revised). If this is correct, it should be noted that the availability of this option is related to the function of the adverbial phrase: adverbial phrases that affect the denotation of the verb, such as manner adverbs, must occur preverbally, whereas all other adverbial phrases can occur either before or after the clause-final verbs in speech (with the postverbal position often being the stylistically marked one if the adverbial phrase is not a PP).

| a. | dat | Jan het boek | <grondig> | las <*grondig>. | manner | |

| that | Jan the book | thoroughly | read | |||

| 'that Jan read the book carefully.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan het boek <in de tuin> | leest <in de tuin>. | locational | |

| that | Jan the book in the garden | reads | |||

| 'that Jan is reading the book in the garden.' | |||||

| c. | dat | Jan het boek | <verleden week> | heeft | gelezen <verleden week>. | time | |

| that | Jan the book | last week | has | read | |||

| 'that Jan read the book last week.' | |||||||

| d. | dat | Jan het boek | <waarschijnlijk> | zal lezen <waarschijnlijk>. | modal | |

| that | Jan the book | probably | will read | |||

| 'that Jan will probably read the book.' | ||||||

The examples in (63) also show that postverbal adverbial phrases can be of different syntactic categories: example (63b) involves a prepositional phrase, example (63c) a nominal phrase, and (63d) an adjectival phrase. The fact that nominal adverbial phrases can occur in the postverbal field shows that the obligatory preverbal placement of nominal arguments cannot be accounted for by assuming a general ban on postverbal nominal phrases (unless one wants to assume that nominal adverbial phrases are in fact PPs with an empty preposition; cf. Larson 1985 and McCawley 1988 for discussion).

The cases in (64) show that adverbial clauses are like clausal complements in that they can be in postverbal position, but differ from them in that they can also be preverbal. Nevertheless, postverbal placement of adverbial clauses is often preferred for stylistic reasons, e.g. to avoid making the middle field too long/complex.

| a. | dat | Jan | [voordat | hij | vertrok] | iedereen | een hand | gaf. | |

| that | Jan | before | he | left | everybody | a hand | gave | ||

| 'that Jan shook hands with everybody before he left.' | |||||||||

| a'. | dat Jan iedereen een hand gaf [voordat hij vertrok]. |

| b. | dat | Jan | [omdat | hij | ziek | was] | naar huis | ging. | |

| that | Jan | because | he | ill | was | to home | went | ||

| 'that Jan went home because he was ill.' | |||||||||

| b'. | dat Jan naar huis ging [omdat hij ziek was]. |

The postverbal field can contain not only arguments of the verb and adverbial modifiers, but also subparts of such constituents. This is shown in the primed examples in (65) for a relative clause and a PP-modifier of the direct object.

| a. | Jan heeft [NP | het boek [rel-clause | dat | Els hem | gegeven | heeft]] | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | the book | that | Els him | given | has | read | ||

| 'Jan has read the book that Els gave him.' | ||||||||

| a'. | Jan heeft [NP het boek] gelezen [rel-clause dat Els hem gegeven heeft]. |

| b. | Jan heeft [NP | het boek | [PP met de gele kaft]] | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | the book | with the yellow cover | read | ||

| 'Jan has read the book with the yellow cover.' | |||||

| b'. | Jan heeft [NP het boek] gelezen [PP met de gele kaft]. |

The examples in (66) show that this option is available not only for modifiers of direct objects, but also for phrases that are more deeply embedded: in (66a) the postverbal relative clause modifies the noun phrase het boekthe book, which is itself part of a PP-complement of the verb, in (66b) the postverbal PP functions as the complement of the predicative AP erg trotsvery proud, and in (66c) the postverbal relative clause modifies a noun phrase embedded in the PP-complement of this predicative AP; the split clausal constituents are italicized and the antecedents of the relative clauses are underlined.

| a. | dat | Jan [PP | op het boek] | wacht [rel-clause | dat | Els hem | toegestuurd | heeft]. | |

| that | Jan | for the book | waits | that | Els him | prt.-sent | has | ||

| 'that Jan is waiting for the book that Els has sent him.' | |||||||||

| b. | dat | Jan [AP | erg trots] | is [PP | op zijn zoon]]. | |

| that | Jan | very proud | is | of his son | ||

| 'that Jan is very proud of his son.' | ||||||

| c. | Dat | Jan [AP | erg trots op het boek] | is [rel-clause | dat | hij | geschreven | heeft]]. | |

| that | Jan | very proud of the book | is | that | he | written | has | ||

| 'that Jan is very proud of the book that he has written.' | |||||||||

If we assume that the postverbal phrase is generated as part of the preverbal nominal/adjectival phrase, there are at least two possible analyses: one is that the larger phrase is base-generated preverbally and that the modifier/complement of this phrase is in extraposed position, and another is that the larger phrase is base-generated postverbally and that the modifier/complement of this phrase is stranded by leftward movement of this phrase. The first proposal is the standard one in early generative grammar; cf. Reinhart (1980) and Baltin (1983). The second was first proposed in Vergnaud (1974) for relative clauses and has become quite popular since Kayne (1994); cf. also Bianchi (1999). An entirely different approach, which is attractive in view of the depth of embedding of the modified phrases, is that the postverbal phrase is not inserted as part of the preverbal phrase, but is generated as an independent phrase; cf. Kaan (1992), Koster (2000), De Vries (2002: §7) and much subsequent work. We will return to this issue in Section 12.4.