- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section discusses some general issues related to the clause-initial position. Subsection I begins with a brief review of the operation that moves the finite verb from its clause-final position into the C-position in the left periphery of the clause; cf. Section 10.1 for a more detailed discussion. Verb movement results in V1 (verb-first) structures, and Subsection II will show how V2 (verb-second) clauses can be derived by subsequent topicalization or question formation. Subsection III will show that the clause-initial position can be filled by at most one constituent. Subsection IV will show that there are no constraints on the syntactic function of the constituent occupying the clause-initial position; it seems that virtually any clausal constituent can occupy this position. This is related to the fact, discussed in Subsection V, that the clause-initial constituent usually has a specific information-structural function. Subject-initial main clauses are an exception in this respect, but Subsection VI will show that there are other reasons for distinguishing such cases. Subsection VII continues by showing that main and embedded clauses exhibit different behavior with respect to their initial position: for example, while the initial position of declarative main clauses is usually filled by the subject or some topicalized element, the initial position of declarative embedded clauses is usually (radically) empty. Subsection VIII concludes by discussing some apparent counterexamples to the claim in Subsection III that the main-clause initial position can be filled by at most one constituent, i.e. that there are no V3 (verb third) clauses.

- I. Verb movement: Verb-first/second

- II. Topicalization and question formation

- III. The clause-initial position contains at most one constituent

- IV. The syntactic function of the constituent in clause-initial position

- V. Clause-initial constituents are semantically marked

- VI. Subject-initial sentences are semantically unmarked

- VII. Main versus embedded clauses

- VIII. Verb-third in main clauses?

- IX. Conclusion

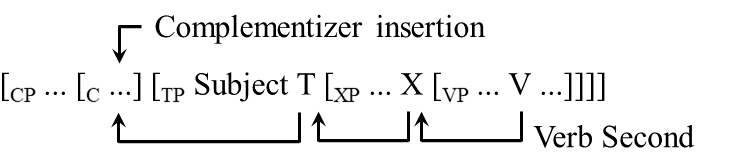

Since Paardekooper (1961) it is usually assumed that complementizers in embedded clauses and finite verbs in main clauses occupy the same structural position in the clause. In the traditional version of generative grammar this is derived as shown in (4). In embedded clauses, the complementizer datthat or ofif must be inserted in the C(omplementizer)-position. In main clauses the finite verb is moved from its original VP-internal position into the C-position via the intermediate T(ense)-position; for theoretical reasons it is usually assumed that the finite verb also moves through all intermediate X-positions, but this will not play a role in the present discussion. Verb movement is blocked in embedded clauses because complementizer insertion is obligatory in this context and thus occupies the target position of the finite verb. The obligatory nature of verb movement in main clauses follows if we assume that the C-position must be filled, but that complementizer insertion is restricted to embedded clauses.

|

The claim that complementizers in embedded clauses and finite verbs in main clauses are placed in the C-position is empirically motivated by Paardekooper’s observation that they have a similar placement with respect to referential subject pronouns such as zijshe. Leaving aside subject-initial main clauses for the moment, the examples in (5) show that subject pronouns are always right-adjacent to the finite verb in main clauses, or right-adjacent to the complementizer in embedded clauses.

| a. | Gisteren | was | zij | voor zaken | in Utrecht. | main clause | |

| yesterday | was | she | on business | in Utrecht | |||

| 'Yesterday she was in Utrecht on business.' | |||||||

| a'. | * | Gisteren was voor zaken zij in Utrecht. |

| b. | Ik | dacht | [dat | zij | voor zaken | in Utrecht was]. | embedded clause | |

| I | thought | that | she | on business | in Utrecht was | |||

| 'I thought that she was in Utrecht on business.' | ||||||||

| b'. | * | Ik dacht dat voor zaken zij in Utrecht was. |

This observation can be explained immediately if we assume that subject pronouns obligatorily occupy the regular subject position, the specifier position of TP, indicated by “Subject” in representation (4).

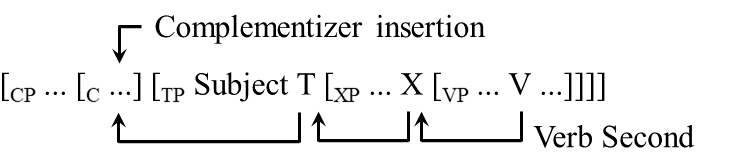

The derivation of V1 and V2-clauses is now very straightforward and simple. The clause-initial position can be identified with the specifier position of CP, indicated in (4) by the dots preceding the C-position. V1-clauses occur when this position remains (phonetically) empty, while V2-clauses occur when this position is filled by a constituent. Prototypical cases of V1-clauses are yes/no questions such as (6a); whether the clause-initial position is really empty or filled by some phonetically empty question operator is difficult to determine; we will postpone this issue to Section 11.2.1. V2-clauses are derived by moving some constituent into the specifier position of CP, the clause-initial position: the movement operation involved, usually called wh-movement, can be used to derive several different kinds of constructions, like the topicalization construction in (6b) and the wh-question in (6c); the traces indicate the original position of the moved phrase.

| a. | Heeft | Jan dat boek | met plezier | gelezen? | V1; yes/no question | |

| has | Jan that book | with pleasure | read | |||

| 'Has Jan enjoyed reading that book?' | ||||||

| b. | Dat boeki | heeft | Jan ti | met plezier | gelezen. | V2; topicalization | |

| that book | has | Jan | with pleasure | read | |||

| 'That book, Jan has enjoyed reading.' | |||||||

| c. | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan ti | met plezier | gelezen? | V2; wh-question | |

| what book | has | Jan | with pleasure | read | |||

| 'Which book has Jan enjoyed reading?' | |||||||

Consider again the representation in (4), repeated below as (7). Functional elements like T and C are usually assumed to contain certain semantic and morphosyntactic features. For example, the functional element T(ense) is assumed to contain the feature [±finite]; this verbal feature is what enables the movement of the finite verb into T, as shown in representation (7). A positive value for this feature enables T to assign nominative case to the subject of the clause, and it is assumed that this morphosyntactic relation between T and the subject allows the latter to move into the specifier position of T; we refer the reader to Section 9.5 for arguments showing that the subject is base-generated in a VP-internal position.

|

For our present discussion it is important to emphasize that the relation between the T-head and the subject is unique: a finite clause has at most one nominative argument. In the active clause in (8a) nominative case is assigned to Peter/hij and in the passive clause in (8b) it is assigned to Marie/zij, but there are no clauses with two nominative nominal arguments: cf. *Hij bezocht zij*He visited she.

| a. | Peter/Hij | heeft | gisteren | Marie/haar | bezocht. | |

| Peter/he | has | yesterday | Marie/her | visited | ||

| 'Pete/He visited Marie/her yesterday.' | ||||||

| b. | Marie/zij | werd | gisteren | door Peter/hem | bezocht. | |

| Marie/she | was | yesterday | by Peter/him | visited | ||

| 'Marie/she was visited by Peter/him yesterday.' | ||||||

It is often assumed that the element C has features related to the illocutionary force of the clause: the feature [±q], for example, determines whether the clause is declarative or interrogative. In Dutch, the feature [±q] differs from [±finite] in that it has no overt morphological manifestation on the finite verb, but it does affect the morphological form of the complementizer: the feature [-q] requires the complementizer to appear as datthat, while [+q] requires it to appear as ofif.

| a. | Marie | zegt [CP | dat[‑Q] | Peter het boek | met plezier | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| Marie | says | that | Peter the book | with pleasure | read | has | ||

| 'Marie says that Peter has enjoyed reading the book.' | ||||||||

| b. | Marie | vraagt [CP | of[+Q] | Peter het boek | met plezier | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| Marie | asks | if | Peter the book | with pleasure | read | has | ||

| 'Marie is asking whether Peter has enjoyed reading the book.' | ||||||||

The examples in (10) show that the value of the feature [±q] also determines which element can occupy the specifier position of CP in main clauses. The (a)-examples first show that it is possible to topicalize either the direct object het boek or the indirect object aan Marie in declarative clauses. The (b) and (c)-examples, on the other hand, show that topicalization is excluded in the presence of a wh-phrase; the feature [+q] then requires the specifier position of CP to be filled by the wh-phrase. Note that (10b'&c') are (marginally) acceptable as echo-questions, but this is of course not the reading intended here.

| a. | Dit boeki | heeft | Peter ti | aan Marie | aangeboden. | |

| this book | has | Peter | to Marie | prt.-offered | ||

| 'This book, Peter has offered to Marie.' | ||||||

| a'. | Aan Mariei | heeft | Peter dit boek ti | aangeboden. | |

| to Marie | has | Peter this book | prt.-offered | ||

| 'To Marie, Peter has offered this book.' | |||||

| b. | Welk boeki | heeft | Peter ti | aan Marie | aangeboden? | |

| which book | has | Peter | to Marie | prt.-offered | ||

| 'Which book has Peter offered to Marie?' | ||||||

| b'. | * | Aan Mariei | heeft | Peter | welk boek ti | aangeboden? |

| to Marie | has | Peter | which book | prt.-offered |

| c. | Aan wiei | heeft | Peter dit boek ti | aangeboden? | |

| to who | has | Peter this book | prt.-offered | ||

| 'To whom has Peter offered this book?' | |||||

| c'. | * | Dit boeki | heeft | Peter ti | aan wie | aangeboden? |

| this book | has | Peter | to who | prt.-offered |

The examples in (11) further show that the specifier position of CP can contain at most one constituent; it is impossible to move more than one constituent into the clause-initial position (but see Subsection VIII for some putative counterexamples). First, although the (a)-examples in (10) have shown that both the direct and the indirect object can be topicalized, example (11a) shows that they cannot be topicalized simultaneously. Second, although example (11b) shows that a clause can contain more than one wh-phrase, example (11b') shows that it is not possible to place more than one wh-phrase in the clause-initial position.

| a. | * | Dit boeki | aan Mariej | heeft | Jan ti tj | aangeboden. |

| this book | to Marie | has | Jan | prt.-offered |

| b. | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan ti | aan wie aangeboden? | |

| which book | has | Jan | to who prt.-offered | ||

| 'Which book did Jan offer to whom?' | |||||

| b'. | * | Welk boeki | aan wiej | heeft ti tj | Jan | aangeboden? |

| which book | to who | has | Jan | prt.-offered |

The examples in (10) and (11) show that the specifier position of CP is similar to the specifier position of T in that it can be occupied by at most one constituent, which must be compatible with its feature specification: just as the specifier of T[+finite] can only be occupied by a nominative argument, the specifier of C[+Q] can only be occupied by a wh-phrase. Note that the C-feature [+q] postulated in this subsection may be part of a larger set of (semantic) features, since clause-initial constituents may have a variety of semantic functions; cf. Subsection V below, and Section 11.3.

The fact, illustrated in (11), that the clause-initial position can contain at most one constituent underlies the standard Dutch constituency test: anything that can occur in the clause-initial position can be analyzed as a constituent. The utility of this test is based on the fact that virtually all clausal constituents can occupy this position. For instance, the examples in (12) show that topicalization and question formation affect arguments and adverbial phrases alike.

| a. | Jan zal | morgen | dat boek | lezen. | |

| Jan will | tomorrow | that book | read | ||

| 'Jan will read that book tomorrow.' | |||||

| b. | Dat boeki | zal | Jan morgen ti | lezen. | object | |

| that book | will | Jan tomorrow | read | |||

| 'That book, Jan will read tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b'. | Wati | zal | Jan morgen ti | lezen? | |

| what | will | Jan tomorrow | read | ||

| 'What will Jan read tomorrow?' | |||||

| c. | Morgeni | zal | Jan ti | dat boek | lezen. | adverbial phrase | |

| tomorrow | will | Jan | that book | read | |||

| 'Tomorrow Jan will read that book.' | |||||||

| c'. | Wanneeri | zal | Jan ti | dat boek | lezen? | |

| when | will | Jan | that book | read | ||

| 'When will Jan read that book?' | ||||||

The examples in (13) show that complementives can also be placed in clause-initial position. This is only illustrated for wh-questions, but similar examples are common in topicalization constructions as well; cf. Boven mijn bed hang ik jouw schilderijAbove my bed, I will hang your painting.

| a. | Ik | wil | dierenarts | worden. | Wati | wil | jij ti | worden? | |

| I | want | vet | become | what | want | you | become | ||

| 'I want to be a vet. What do you want to be?' | |||||||||

| b. | Ik vond de film | saai. | Hoei | vond | jij | hem ti? | |

| I found the movie | boring. | how | found | you | him | ||

| 'I thought the movie boring. What did you think of it?' | |||||||

| b'. | Ik | hang | jouw schilderij | boven mijn bed. | Waari | hang | jij | het mijne ti? | |

| I | hang | your painting | above my bed | where | hang | you | the mine | ||

| 'I will hang your painting over my bed. Where will you hang mine?' | |||||||||

It should be noted, however, that the clause-initial position is not only accessible to clausal constituents, but can sometimes also contain parts of clausal constituents. This is illustrated in (14) for the complementive AP trots op mijn vader: in (14b) the entire complementive AP has been moved, in (14b) the PP-complement is extracted from the AP, and in (14c) it is even a subpart of the pronominal PP-complement daaropof it has been moved into the clause by R-extraction.

| a. | Jan is nog steeds [AP | trots [PP op zijn diploma]]. | |

| Jan is still | proud of his diploma |

| b. | [AP Trots [PP op zijn diploma]]i is Jan nog steeds ti. |

| b'. | [PP op zijn diploma] is Jan nog steeds [AP | trots ti ]. |

| b''. | Daari is Jan nog steeds [AP | trots [PP op ti ]]. |

The examples in (15) give another examples involving R-extraction: although the (a) example shows that prepositional objects are usually wh-moved as a whole, the primed example shows that they can easily be split if they have the pronominalized form waar+P; cf. Chapter P36 for a detailed discussion.

| a. | <Naar> | wie | zoek | je <*naar>? | |

| for | who | look | you | ||

| 'Who are you looking for?' | |||||

| b. | Waar | <naar> | zoek | je <naar>? | |

| where | for | look | you | ||

| 'What are you looking for?' | |||||

Example (15b) shows a similar optional split with so-called wat-voor phrases; cf. Section N17.2.2.

| a. | [Wat | voor een boek]i | wil | je ti | lezen? | |

| what | for a book | want | you | read | ||

| 'What kind of a book do you want to read?' | ||||||

| b. | Wati | wil | je | <voor een boek> | lezen? | |

| what | want | you | for a book | read | ||

| 'What kind of a book do you want to read?' | ||||||

We must therefore be careful not to conclude too quickly that we are dealing with a clausal constituent when a particular string of words occurs in clause-initial position: we can only conclude that we are dealing with a constituent, which may be either a clausal constituent or a subcomponent of a clausal constituent.

The previous subsection has shown that there are no syntactic restrictions on the constituent in the clause-initial position, the specifier position of CP; in principle, any clausal constituent can be placed in this position. In this respect, the specifier position of CP is of a completely different nature than the specifier position of TP, which is a designated position of the subject. The movements involved in filling these specifiers are also of a very different nature, which is sometimes expressed by saying that there is a distinction between A and A'-movement. A(rgument)-movement is restricted to nominal arguments, i.e. subjects and direct/indirect objects. These movements are triggered by morphosyntactic features like [±finite] or [±agreement], which play a role in syntactic relations like structural case (nominative, accusative and dative) assignment and subject/object-verb agreement. A'-movements are not restricted to nominal arguments and are not triggered by morphosyntactic but by semantic features. Features that can play a role in topicalization constructions are [±topic] and [±focus]. The feature [+topic] introduces the clause-initial constituent as the active discourse topic. An example such as (17a) introduces the referent of the direct object as a (new) discourse topic; consequently it is likely that in the following sentence more information about this referent is provided, i.e. that the pronoun hij is taken to refer to Peter (which is indicated by coindexing). The feature [±focus] marks the clause-initial constituent as somehow noteworthy, which is emphasized by the fact that this constituent is usually assigned extra accent (here indicated by small caps); e.g. (17b) contrasts the referent of the clause-initial constituent with other entities in a contextually given set.

| a. | Peteri | heb | ik | nog | niet ti | gesproken. | Hiji | is nog | op vakantie. | |

| Peter | have | I | not | yet | spoken | he | is still | on vacation | ||

| 'As for Peter, I have not spoken to him yet. He is still on vacation.' | ||||||||||

| b. | Peteri | heb | ik | nog | niet ti | gesproken | (maar | de anderen | wel). | |

| Peter | have | I | not | yet | spoken | but | the others | aff | ||

| 'Peter, I have not spoken to yet, but I did speak to the others.' | ||||||||||

The fact that topicalization does not occur in embedded clauses suggests that the features [±topic] and [±focus] can only be found in the C-heads of main clauses. This is not the case for the feature [±Q], as can be seen from the fact, illustrated in (18), that interrogative clauses can be embedded.

| a. | Ik | weet | niet [CP | of[+Q] | ik | dit boek | zal | lezen]. | |

| I | know | not | if | I | this book | will | read | ||

| 'I do not know if I will read this book.' | |||||||||

| b. | Ik | weet | niet [CP | welk boeki | (of[+Q]) | ik ti | zal | lezen]. | |

| I | know | not | which book | if | I | will | read | ||

| 'I do not know which book I will read.' | |||||||||

Note in passing that the interrogative complementizer ofif is optional in cases such as (18b), which is related to the fact that there is a certain preference not to pronounce the complementizer when the clause-initial position is filled. This phenomenon is also found in other languages; cf. Chomsky & Lasnik (1977), where this is explained in terms of the so-called doubly-filled-comp filter, and Pesetsky (1997/1998), Dekkers (1999: §3), and Broekhuis & Dekkers (2000), where it is explained in optimality-theoretic terms.

There are also features such as [±relative] that occur in embedded clauses only. This feature creates relative clauses and can be held responsible for the movement of relative pronouns. The percentage signs in the examples in (19) express that the complementizer dat[+rel] is usually not pronounced in standard Dutch, but that it was possible in Middle Dutch and is still possible in various present-day Dutch dialects; cf. Pauwels (1958), Dekkers (1999) and the references cited there.

| a. | de brief [CP | diei | (%dat[+rel]) | ik | gisteren ti | ontvangen | heb]. | |

| the letter | which | that | I | yesterday | received | have | ||

| 'the letter which I received yesterday' | ||||||||

| b. | de plaats [CP | waari | (%dat[+rel]) | ik | ga ti | slapen] | |

| the place | where | that | I | go | sleep | ||

| 'the place where I am going to sleep' | |||||||

The previous subsection has shown that clause-initial constituents usually play a specific information-structural role (wh-phrase, topic, focus, etc.) in the clause. This was confirmed by the results of a corpus study: “Non-subject material in the Vorfeld [= clause-initial position] is characterized by its (relative) importance” (Bouma 2008:48). The reason for providing this quote is that Bouma also found that this general characterization does not extend to subject-initial clauses: these are special in that they are the most unmarked way of asserting a proposition. That subject-initial clauses are unmarked is clear from the fact that they are generally used when the whole sentence consists of new information: the word order in example (20a) is the one we typically get as an answer to the question Wat is er gebeurd?What has happened?. This raises the question of whether subject-initial main clauses have the same overall structure as other V2-constructions, as is assumed in the more traditional versions of generative grammar, where example (20a) is derived as in (20b).

| a. | Marie | heeft | haar boek | verkocht. | |

| Marie | has | her book | sold | ||

| 'Marie has sold her book.' | |||||

| b. |  |

If the movement into the specifier of CP is indeed motivated by some semantic feature, the fact that (20a) is the unmarked way of expressing the proposition have read (Marie,this book) would be quite surprising. Moreover, Section 9.3 has shown that there are several other striking differences between clause-initial subjects and other topicalized phrases. The most conspicuous difference is that the former can be a phonetically reduced pronoun, whereas the latter cannot; cf. Zwart (1997). Consider the examples in (21). The primeless examples show that the subject can be clause-initial regardless of its form: it can be a full noun phrase such as Marie, a full pronoun such as zij, or a phonetically reduced pronoun such as ze. The primed examples show that topicalized objects are different: topicalization is possible when they take the form of a full noun phrase such as Peter or a full pronoun such as hem, but not when they take the form of the weak (phonetically reduced) pronoun ’m. This is because topicalized objects must be accented (which is indicated by small caps), whereas clause-initial subjects can remain unstressed.

| a. | Marie helpt | Peter/hem/’m. | ||||

| Marie helps | Peter/him/him | |||||

| 'Marie is helping Peter/him.' | ||||||

| a'. | Peter | helpt | Marie/zij/ze. | |||

| Peter | helps | Marie/she/she | ||||

| 'Peter, Marie/she is helping.' | ||||||

| b. | Zij | helpt | Peter/hem/’m | ||||

| she | helps | Peter/him/him. | +him | helps | Marie/she/she | ||

| 'She is helping Peter/him.' | |||||||

| b'. | Hem | helpt | Marie/zij/ze. | ||||

| 'Him, Marie/she is helping.' | |||||||

| c. | Ze | helpt | Peter/hem/’m | ||||

| she | helps | Peter/him/him. | |||||

| 'She is helping Peter/him.' | |||||||

| c'. | * | ʼM | helpt | Marie/zij/ze. |

| him | helps | Marie/she/she |

That topicalized phrases must be accented can also be illustrated by the examples in (22). The (a)-examples show that while the adverbial proform daarthere can easily be topicalized, the phonetically reduced form er cannot. The (b)-examples illustrate the same for cases in which the R-words are part of a pronominal PP.

| a. | Jan heeft | daar/er | gewandeld. | |

| Jan has | there/there | walked | ||

| 'Jan has walked there.' | ||||

| a'. | Daar/*Er | heeft | Jan gewandeld. | |

| there/there | has | Jan walked |

| b. | Jan heeft daar/er mee gespeeld. | |

| Jan has there/there with played | ||

| 'Jan has played with that/it.' |

| b'. | Daar/*Er | heeft | Jan mee | gespeeld.’ | |

| there/there | has | Jan with | played |

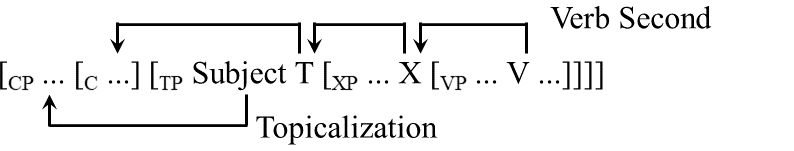

We can easily account for these differences between subject-initial main clauses and other types of V2-clauses if we assume that they have the different representations in (23): if sentence-initial subjects are not topicalized but are in the canonical subject position (i.e. the specifier of TP), there is no reason to expect that such constructions will give rise to a marked interpretation or require a special intonation pattern.

| a. | Subject-initial main clause |

|

| b. | Topicalization and question formation in main clause |

|

Accepting the two structures in (23) would also make it possible to explain the contrast in verbal inflection in the examples in (24) by making the form of the finite verb sensitive to the position it occupies; when the verb is in T, as in (24a), second-person singular agreement is realized by a -t ending, but when it is in C, as in (24b&c), it is realized by a null morpheme. See Zwart (1997), Postma (2011), and Barbiers (2013) for further discussion.

| a. | Jij/Je | loop-t | niet | erg snel. | |

| you/you | walk-2sg | not | very fast | ||

| 'You do not walk very fast.' | |||||

| b. | Erg snel | loop-Ø | jij/je | niet. | |

| very fast | walk-2sg | you/you | not | ||

| 'You do not walk very fast.' | |||||

| c. | Hoe snel loop-Ø | jij/je? | |

| how fast walk-2sg | you/you | ||

| 'How fast do you walk?' | |||

The discussion above thus shows that there are good reasons not to follow the traditional generative view that Dutch main clauses are always CPs; subject-initial main clauses may be special in that they are TPs. This hypothesis can help us account for the following facts: (i) subject-initial clauses are unmarked assertions, (ii) sentence-initial subjects can be a reduced pronoun and (iii) subject-verb agreement can be sensitive to the position of the subject.

There is a striking difference between the clause-initial positions of main and embedded finite declarative clauses: the examples in (25) show that while the former are usually filled by the subject or a topicalized phrase, the latter are usually empty. Note that we have placed the complementizers in the primed (b)-examples with in brackets because we have seen that the phonetic content of a complementizer is often omitted if the specifier of CP is filled by phonetic material; cf. the discussion of the doubly-filled-comp filter in Subsection V.

| a. | Jan heeft | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | ||

| 'Jan has read Vaslav by Arthur Japin.' | ||||

| a'. | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | heeft | Jan gelezen. | |

| Vaslav by Arthur Japin | has | Jan read | ||

| 'Vaslav by Arthur Japin Jan has read.' | ||||

| a''. | * | Ø | heeft | Jan | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen. |

| * | Ø | has | Jan | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read |

| b. | Ik | denk [CP Ø | dat [TP | Jan | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen | heeft]]. | |

| I | think | that | Jan | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | has | ||

| 'I think that Jan has read Vaslav by Arthur Japin.' | ||||||||

| b'. | * | Ik | denk [CP | Jani | (dat) [TP ti | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen | heeft]]. |

| I | think | Jan | that | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | has |

| b''. | * | Ik | denk [CP | Vaslav van Arthur Japini | (dat) [TP | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]]. |

| I | think | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | that | Jan | read | has |

Such a difference between finite main and dependent clauses does not arise in the case of interrogative clauses. The examples in (26) show that in both cases the initial position is phonetically empty in yes/no questions, but filled with a wh-phrase in wh-questions.

| a. | Ø | Heeft | Jan | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen? | |

| Ø | has | Jan | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | ||

| 'Has Jan read Vaslav by Arthur Japin?' | ||||||

| a'. | Wati | heeft | Jan ti | gelezen? | |

| what | has | Jan | read | ||

| 'What has Jan read?' | |||||

| b. | Ik | weet niet [CP | Ø of [TP | Jan Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen | heeft]]. | |

| I | know not | Ø if | Jan Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | has | ||

| 'I do not know whether Jan has read Vaslav by Arthur Japin.' | |||||||

| b'. | Ik | weet niet [CP | wati | (of) [TP | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]]. | |

| I | know not | what | if | Jan | read | has | ||

| 'I do not know what Jan has read.' | ||||||||

Finite main clauses and embedded clauses do differ in that only the latter can be used as relative clauses. The examples in (27) show that such clauses require some relative element in the clause-initial position; we already mentioned in Subsection V that the complementizer dat is usually omitted in standard Dutch relative clauses.

| a. | Dit is de roman [CP | diei | (*dat) [TP | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]]. | |

| this is the novel | rel | that | Jan | read | has | ||

| 'This is the novel that Jan has read.' | |||||||

| b. | * | Dit is de roman [CP Ø | (dat) [TP | Jan | die | gelezen | heeft]]. |

| this is the novel | that | Jan | rel | read | has |

The initial position of infinitival clauses is usually phonetically empty. Examples such as (28a) are possible, but seem to be of an idiomatic nature in colloquial speech; cf. Section 4.2. Note that the complementizer in such examples cannot be realized overtly, and that PRO stands for the implicit subject of the infinitival clause. For examples such as (28b), it is sometimes assumed that the clause-initial position is filled by a phonetically empty operator OP; we will not discuss such examples here, but refer the reader to Section N16.3.3 for further discussion.

| a. | Ik | weet | niet [CP | wati [C Ø] [TP PRO ti | te doen]]. | |

| I | know | not | what | to do | ||

| 'I do not know what to do.' | ||||||

| b. | Dat | is een auto [CP OPi [C | om] [TP PRO ti | te zoenen]]. | |

| that | is a car | comp | to kiss | ||

| 'That is a car to be delighted about/an absolutely delightful car.' | |||||

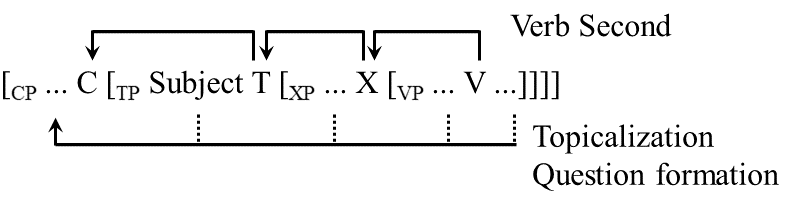

This subsection briefly discusses a number of possible counterexamples to the claim in Subsection III that the main-clause initial position can be filled by at most one clausal constituent, i.e. that there are no main clauses in Dutch with the verb in the third or some later position; this is usually referred to as the V2-restriction (although it is clearly not intended to exclude V1-clauses). This restriction follows from the well-established generalization that the finite verb in main clauses moves from the clause-final verb position to the C-position (cf. Section 10.1, sub II), in tandem with the proposal that the specifier of this C-head is like all specifier positions in that it can be filled by at most one constituent.

|

Since this proposal has played and continues to play a crucial role in both the syntactic description of Dutch and the formalization of generative grammar since the late 1970s, it is not surprising that the V2-restriction has been subjected to extensive scrutiny, which has resulted in a collection of potential counterexamples. Here, we discuss a smaller selection of such cases on the basis of Zwart (2005) and Van der Wouden (2015). However, before we start, it is important to point out that the V2-restriction does not exclude utterances of the kind in (30), in which the italicized elements are widely assumed to be main-clause external; these elements can all be used in isolation (e.g. to answer a question, to call someone, or to express emotion about something) and are not clausal constituents (i.e. they are typically optional and clearly do not function as an argument, modifier, or predicate in the following main clause). Their main-clause external status is also clear from the fact that they can easily be separated from the main clause by a clear intonation break; cf. Section C37.0 for further discussion of these examples. So the V2-restriction does not always apply to complete utterances, but only to their sentential part, i.e. the non-italicized part of the utterances in (30).

| a. | Ja, | dat | wist | ik | al. | polar yes/no | |

| yes | that | knew | I | already | |||

| 'Yes, I already knew that.' | |||||||

| b. | Jan, | er | is telefoon | voor je. | vocative | |

| Jan | there | is phone.call | for you | |||

| 'Jan, there is a phone call for you.' | ||||||

| c. | Lieve help, | hij is ziek. | interjection | |

| good grief, | he is ill | |||

| 'Good grief, he is ill!' | ||||

A possible counterexample to the V2-restriction is the so-called left-dislocation construction, which occurs in the two subtypes shown in (31), where the indices indicate coreference. Crucially, however, the left-dislocated element is resumed in the sentence: the proper name Jan in (31) is repeated by a referential or demonstrative personal pronoun functioning as the direct object. This suggests that the left-dislocated element is not a clausal constituent: it is optional and cannot be analyzed as the direct object of the sentence because the pronoun already has this function.

| a. | Jani, | ik | heb | hemi | niet | gezien. | hanging-topic LD | |

| Jan | I | have | him | not | seen | |||

| 'Jan, I have not seen him.' | ||||||||

| b. | Jani, | diei | heb | ik | niet | gezien. | contrastive LD | |

| Jan | dem | have | I | not | seen | |||

| 'Jan, I have not seen him.' | ||||||||

Furthermore, the fact that left-dislocated elements are typically followed by a distinct intonation break shows that we are again dealing with main-clause external elements. This can be supported by the fact that the proper name Jan in (31) can be separated from the sentence by the polar element neeno in (30a); if nee is indeed main-clause external, this holds all the more for the proper names in (32). For a detailed discussion of left dislocation, see Section C37.2. We conclude that left-dislocation is not a violation of the V2-restriction.

| a. | Jani, | nee, | ik | heb | hemi | niet | gezien. | [hanging-topic LD] | |

| Jan | no | I | have | him | not | seen | |||

| 'Jan, no, I have not seen him.' | |||||||||

| b. | Jani, | nee, | diei | heb | ik | niet | gezien. | contrastive LD | |

| Jan | no | dem | have | I | not | seen | |||

| 'Jan, no, I have not seen him.' | |||||||||

This test shows that there are also main-clause external clauses; cf. Haegeman & Greco (2018) and Greco & Haegeman (2020) and the references cited there. This holds for standard conditional clauses with the (optional) resumptive adverb dan, as in (33a), but there are also cases without a resumptive element, as in (33b); in the former the main-clause external clause specifies the condition(s) that make the consequence true, while in the latter it specifies the conditions that make the consequence relevant.

| a. | [Als | je | klaar | bent]i, | Jan, | dani | mag | je | weg. | truth | |

| if | you | ready | are, | Jan, | that | may | you | away | |||

| 'If you are ready, Jan, you may leave.' | |||||||||||

| b. | [Als | je | honger | hebt]i, | Jan, | het eten | staat | in de kast. | relevance | |

| if | you | hunger | have | Jan, | the food | stands | in the cupboard | |||

| 'In case you are hungry, Jan, there is food in the cupboard.' | ||||||||||

Discourse/speech-act related phrases can also occur to the left of the sentence: two examples are given in (34).

| a. | [Als | je | het | mij | vraagt]i, | nee, | ik | had | het | niet | verwacht. | |

| if | you | it | me | ask | no | I | had | it | not | expected | ||

| 'If you ask me, no, I had not expected it'. | ||||||||||||

| b. | Eerlijk gezegd, | Jan, | ik | had | het | niet | verwacht. | |

| honestly spoken | Jan | I | had | it | not | expected | ||

| 'Honestly speaking, Jan, I had not expected it'. | ||||||||

A final set of main-clause external clauses/phrases without a resumptive element are the so-called circumpositional frame setters: in the examples in (35) they specify the circumstances (e.g. the contextual frame) in which the answer to the questions or the action referred to by the imperative become relevant; cf. Greco & Haegeman (2020:§4.4) for further discussion and references. Of course, putative V3-constructions only arise in the case of wh-questions such as (35a), since yes/no-questions and imperatives are themselves V1. The examples in (35) also show that the adverb dan may be added, but this does not necessarily mean that we are dealing with contrastive left-dislocation constructions: in such constructions resumptive elements are obligatory moved to the main-clause initial position. We may be dealing with a temporal adverb or a particle in example (35) below.

| a. | Als | er | nog | een probleem | is, | wie | kan | ik | (dan) | bellen? | wh-question | |

| if | there | yet | a problem | is | who | can | I | then | call | |||

| 'If there is another problem, who can I call?' | ||||||||||||

| b. | Als | er | nog | een probleem | is, | kan | ik | (dan) | bellen? | yes/no-question | |

| if | there | still | a problem | is | can | I | then | call | |||

| 'If there is another problem, can I call?' | |||||||||||

| c. | Als | er | nog | een probleem | is, | bel | (dan). | imperative | |

| if | there | still | a problem | is | call | then | |||

| 'If there is another problem, call.' | |||||||||

The acceptability contrast between the primeless examples in (36), together with the acceptability of the examples in (35), have been argued to show that the construction under discussion has a special property: the subject cannot occur in main-clause initial position. This conclusion is supported by the fact that (36a) becomes perfectly acceptable when dan is moved into main-clause initial position with concomitant subject-verb inversion (which also enables the non-temporal reading of dan found in conditional constructions).

| a. | * | Als | er | nog | een probleem | is, | ik | bel | je | (dan). |

| if | there | yet | a problem | is | I | call | you | then |

| a'. | Als | er | nog | een probleem | is, | (dan) | bel | ik | je. | |

| if | there | yet | a problem | is | then | call | I | you | ||

| Intended: 'If there is another problem, I will call you.' | ||||||||||

| b. | Als | er | nog | een probleem | is, | mij | moet | je | niet | bellen. | |

| if | there | yet | a problem | is | me | must | you | not | call | ||

| 'If there is another problem, donʼt call me.' | |||||||||||

The unacceptability of subject-initial main clauses in (36a) is explained in Haegeman & Greco (2018) and Greco & Haegeman (2020) by appealing to a (cartographic) version of the hypothesis that they differ in categorical status from clauses with subject-verb inversion. In terms of our discussion in Sections 9.3 and 10.1, standard Dutch subject-initial main clauses are TPs while main clauses with subject-verb inversion are CPs. This proposal is supported by the fact, illustrated in (37), that subject-initial main clauses are possible with interrogative or focused subjects, because it can then be assumed that they must be wh-moved to the specifier of CP for semantic reasons (i.e. to take scope); cf. Section 11.3. Note in passing that West Flemish allows subject-initial main clauses in (36a), because it is assumed that this language variety differs from standard Dutch in that such main clauses are also CPs.

| a. | Als | er | nog | een probleem | is, | wie | bel | je | (dan)? | |

| if | there | yet | a problem | is | who | call | you | then | ||

| 'If there is another problem, who will you call?' | ||||||||||

| b. | Als | er | nog | een probleem | is, | zij/*ze | zal | je | (dan) | niet | helpen. | |

| if | there | yet | a problem | is | she/she | will | you | then | not | help | ||

| 'If there is another problem, she will not help you?' | ||||||||||||

This concludes our brief digression on main-clause external clauses of the kind in (33) to (37); see Section 10.3.2 for more discussion of the main-clause external status of als-clauses in conditional-like constructions, Haegeman & Greco (2018) and Greco & Haegeman (2020) for a detailed theoretical account of the difference in acceptability of (36a) in standard Dutch and West Flemish, and Section 8.3.3, sub XIII, for other possible uses of speech-act related adverbs. We will now return to our discussion of the properties of left-dislocation and their relevance for diagnosing possible V3-constructions.

We have seen earlier that the distribution of vocatives, the polar elements ja/nee and other demonstrably main-clause external phrases can be used as diagnostics to test whether a sentence-initial phrase is internal or external to the clause. Since left-dislocated strings of words can be resumed by a pronominal element functioning as a clausal constituent, we can safely assume that such strings are also constituents. This excludes appositional structures of the type in (38a) from the set of possible V3-structures: since the string Jan, de bank directeur in (38b) is left-dislocated, it must be a single constituent. Note that (38b) shows again that left-dislocated phrases can be separated from the main clause by the polar element neeno.

| a. | Jan, de bankdirecteur, | heb ik niet gezien. | apposition | |

| Jan, the bank.director | have I not seen | |||

| 'Jan, the bank director, I have not seen.' | ||||

| b. | [Jan, de bankdirecteur]i, | nee, | die | heb | ik | niet | gezien. | |

| Jan, the bank.director, | no | dem | have | I | not | seen | ||

| 'Jan, the bank director, no, I have not seen him.' | ||||||||

A more complex case of a similar kind is provided in (39). First, compare the two (a)-examples: one possibility is that the primed example is derived from the more or less synonymous primeless example by leftward movement of the adverbial gisteren, which would imply that we are dealing with a V3-clause. However, this analysis is contradicted by the fact that the left-dislocation construction in the (b)-example is perfectly acceptable. This shows that dat ijsje gisteren in (39a') is a single constituent and that we are dealing with a V2-sentence; cf. Barbiers (1995a:§4.7/1995b) for an analysis that would be compatible with this conclusion and Section N16.3.6 for a further discussion of this kind of adverbial modification.

| a. | Dat ijsje | was gisteren | erg lekker. | adverbial modifier | |

| that ice.cream | was yesterday | very nice |

| a'. | Dat ijsje gisteren | was | erg lekker. | |

| that ice.cream yesterday | was | very nice |

| b. | Dat ijsje gisteren, | ja, | dat | was | erg lekker. | |

| that ice.cream yesterday | yes, | dem | was | very nice |

Note that the resumptive distal demonstratives die/datthat in the left-dislocation constructions in (31)-(39) cannot be replaced by their proximate counterparts deze/ditthis. In this respect they are similar to the distal pronouns used as topic-shifting devices discussed in Section 19.2.3.2, sub IIA2, which indicate that the discourse topic (the entity the discourse is about) is changed. This is illustrated in (40); while the subject pronouns zeshe/hijhe in the (a)-examples can in principle be coreferential with either the subject (i.e. the topic) or the object (contained in the comment) of the preceding clause, the distal demonstrative can only be coreferential with the object, making it the topic of the continuation of the discourse.

| a. | Elsi | ontmoette | Janj | en | zei | vertelde | hemj | dat ... | no topic shift | |

| Els | met | Jan | and | she | told | him | that | |||

| 'Els met Jan and she told him that ...' | ||||||||||

| a'. | Elsi | ontmoette | Janj | en | hiji | vertelde | haarj | dat ... | topic shift? | |

| Els | met | Jan | and | he | told | her | that | |||

| 'Els met Jan and he told her that ...' | ||||||||||

| b. | Elsi | ontmoette | Janj | en | diej/*i | vertelde | haari | dat ... | only topic shift | |

| Els | met | Jan | and | that.one | told | her | that | |||

| 'Els met Jan and he told her that ...' | ||||||||||

In essence, the resumptive distal demonstratives in the contrastive left-dislocation constructions in (31)-(38) have the same function in that they introduce the left-dislocated elements as the topic of the forthcoming discourse; we can thus assume that we are dealing with elements with a similar discourse function as the distal demonstrative in (40b). This can also be supported by the fact discussed in Section 11.2.2 that topic-shift pronouns can often be omitted, as shown in (41a). Example (41b) shows that the same is true for the resumptive pronoun in contrastive left-dislocation constructions.

| a. | Weet | jij | waar | Jani | is? | Nee, | diei | heb | ik | niet | gezien? | topic shift | |

| know | you | where | Jan | is | Nee, | that | have | I | not | seen | |||

| 'Do you know where Jan is? No, I have not seen him.' | |||||||||||||

| b. | Jani, | nee, | diei | heb | ik | niet | gezien. | contrastive LD | |

| Jan | no | dem | have | I | not | seen | |||

| 'Jan, no, I have not seen him.' | |||||||||

We will show that the conclusion that the distal demonstratives in left-dislocation and topic-shift constructions are similar (or even identical) may help us to shed new light on the final possible violation of the V2-restriction that we will consider here. At first glance, the examples in (42) may seem to be similar to the cases in (39), but they differ crucially with respect to the status of the element between the subject het ijsje and the finite verb was; we will argue that this motivates an entirely different analysis.

| a. | Het ijsje | was echter | erg lekker. | conjunctive adverbs | |

| the ice.cream | was however | very nice |

| a'. | Het ijsje echter | was | erg lekker. | |

| the ice.cream however | was | very nice |

| b. | Het ijsje echter, | dat | was | erg lekker. | |

| the ice.cream however | dem | was | very nice |

The adverbial gisteren can well be seen as a restrictive modifier of the subject, as is clear from the fact that the subject in (43a) differs in reference from the noun phrase in the comparative dan-phrase: the discourse is about a larger set of ice cream entities and the adverbials gisteren and vandaag help to uniquely identify the intended entities. The adverbial echter, on the other hand, does not have this function: example (43b) is not suitable, because the use of the definite subject het ijsje suggests that there is only one uniquely identified ice cream in the discourse, which is later contradicted by the use of the noun phrase het ijsje vandaag.

| a. | Dat ijsje gisteren | was lekkerder | dan | het ijsje vandaag. | |

| that ice.cream yesterday | was tastier | than | the ice.cream today |

| b. | $ | Het ijsje | echter | was lekkerder | dan | het ijsje vandaag. |

| that ice.cream | however | was tastier | than | the ice.cream today |

This contrast between the two examples in (43) suggests that the adverbial echter is not part of the noun phrase, which may suggest that we are dealing with a genuine V3-construction; this was the conclusion in Van der Wouden (2015), who examined this case more closely and concluded that we are dealing with a construction in the sense of construction grammar:

| C is a construction iffdef C is a form-meaning pair <Fi, Si> such that some aspect of Fi or some aspect of Si, is not strictly predictable from C’s component parts or from other previously established constructions (Goldberg:4). |

Van der Wouden’s claim is that examples such as (43b) satisfy this description: he points to the properties of the construction at hand listed in (45):

| a. | marked syntax: verb-third main clauses; |

| b. | lexically grounded: limited number of particles that are difficult to characterize independently; |

| c. | pragmatically motivated: marking of non-default discourse topics. |

We will discuss the three issues in (45) in more detail later, but first we want to note that Van der Wouden (2015:§3.1) claims that examples such as (43b) are not part of colloquial speech; they are actually “quite rare in modern Dutch, and restricted to formal, written variants of the language […]. I assume that the construction is acquired at quite high an age, and only from written input; many speakers never ever use it actively.” If this is really true, we would have to conclude that the construction is not part of core syntax but of the periphery of grammar; this would make a lexical approach (i.e. as idiomatic expression) to the construction in question unproblematic for most generative linguists, and it would therefore be fully justified to stop our search for an explanation of examples such as (43). However, it appears that we can do better by showing that the three claims in (45) themselves are not unproblematic.

We begin with the claim in (45b): (i) there are only a limited number of particles that occur in the construction, and (ii) that they are difficult to characterize independently. It is not fully clear to us what is meant by (ii), but it seems that the set of “particles” that can occur in the construction is a substantial subset of the conjunctive adverbials discussed in Section 8.2.2, sub XII. The adverbs listed in Van der Wouden (2015) are: althansat least, daarentegenon the contrary, dusso, therefore, echterhowever, evenwelhowever, immersfor, nunow, tochyet. Conjunctive adverbials can be characterized as adverbials that “link the sentence to the preceding context, for example by expressing a contrast” (Haeseryn et al. 1997:1297; our translation). Van der Wouden correctly claims that they seem to perform the same function in the construction under discussion: they cannot be used as the opening sentence of a discourse (without producinging the idea that it is the continuation of an earlier discourse). It is therefore unclear how an appeal to these “particles” could motivate the postulation of a construction in the sense of (44).

We have seen that we cab assume that the adverb echter in (43b) is not part of the subject het ijsje. Van der Wouden (2015:§3.1) provides additional evidence for this by pointing out that the two need not form an intonational unit (which is more or less expected if they functioned as a clausal constituent), and they cannot be used together as an answer to a wh-question; this is shown in (46).

| a. | Het ijsje, | echter, | was het lekkerst. | |

| the ice.cream | however, | was the tastiest |

| b. | Wat | was | het lekkerst? | Het ijsje | (*echter). | |

| what | was | the tastiest | the ice.cream | however |

The crucial question, however, is whether this conclusively shows that we are dealing with a V3-sentence. The answer seems to be negative: one option would be to assume that the conjunctive adverbial is epenthetic, since epenthetic phrases are often assumed to be clause-external; cf. Zwart (2005). But an even better argument can be based on (42b), which might receive an analysis along the lines of (47a); we have added example (47b) to show that the demonstrative agrees in gender with the noun phrase (and not e.g. with a reduced clause, since we would then expect the neuter demonstrative to appear throughout).

| a. | Het ijsjei, | echter, | [dati | was | erg lekker]. | |

| the ice.cream | however | dem | was | very nice | ||

| 'The ice cream, however, it was very nice.' | ||||||

| b. | De jongeni, | echter, | [diei | arriveerde | te laat]. | |

| the boy | however | dem | arrived | too late | ||

| 'The boy however, he came too late.' | ||||||

What we have in (47) are contrastive left-dislocation constructions, in which the dislocated phrase precedes a main-clause external discourse particle. This is an independently motivated possibility, as is clear from the example in (48), taken from Van der Wouden (2015:552). The fact that this example is characterized “as old fashioned and bookish to modern ears” may support the analysis proposed in (47), since this special status would then be transferred to examples such as (43b), explaining Van der Wouden’s earlier claims that it is quite rare in modern Dutch, restricted to formal variants of the language, and acquired late.

| Vader | wil | naar huis. | Echter, | dat | is geen goed idee. | ||

| vader | wants | to home | however | that | is no good idea | ||

| 'Father wants to go home. However, that is not a good idea.' | |||||||

Since we have seen in (41b) above that resumptive pronouns can be omitted in left-dislocation constructions, we now also have a straightforward way to derive the putative V3-construction, as in (49).

| a. | Het ijsjei, | echter, | [dati | was | erg lekker]. | |

| the ice.cream | however | dem | was | very nice | ||

| 'The ice cream, however, it was very nice.' | ||||||

| b. | De jongeni, | echter, | [diei | arriveerde | te laat]. | |

| the boy | however | dem | arrived | too late | ||

| 'The boy, however, he came too late.' | ||||||

So far we have seen that there are reasons not to accept the claims in (45a&b). This leaves us with (45c), according to which the construction marks a non-default discourse topics. This is probably the core property that led Van der Wouden to conclude that we are dealing with a construction in the sense of (44): in the V3 analysis adopted in Van der Wouden (2015), this property “is not strictly predictable from C’s component parts or from other previously established constructions”. However, this is different in the left-dislocation analysis in (47), because we have seen that the resumptive distal demonstratives in left-dislocation constructions have a similar discourse function as the distal demonstratives in topic-shift constructions: the introduction of a new (i.e. non-default) discourse topic. This shows that the putative V3-examples of the kind under discussion do not meet the criteria in (44) for being called a construction in the sense of construction grammar.

We conclude with another case that seems to be related to the previous cases, but which may require a completely different analysis. Van der Wouden (2020), Haegeman & Trotzke (2020) and Trotzke & Haegeman (2022) provide case studies of the distribution of the (non-temporal) discourse particles nunow and danthen, which seem to behave like conjunctive adverbs in that they (often) introduce non-default discourse topics (cf. (45c)). However, they seem to have a wider distribution than most conjunctive adverbs in that they can both precede and follow the initial constituent, as shown in (50).

| a. | Loop | naar het kerkplein. | |

| walk | to the church.square |

| b. | <Dan> | naast de kerk <dan> | woont | mijn tante. | |

| then | next.to the church | lives | my aunt | ||

| 'Walk to the church. Then next to the church lives my aunt.' | |||||

However, the examples in (51) strongly suggest that the particle preceding naast de kerk is part of the PP, and consequently that we can simply derive (51b') from (51b) by topicalization of the PP. This would imply that (50b) with the particle dan preceding the PP is different from the earlier cases with conjunctive adverbs, and that an appeal to left dislocation is not needed, leaving open the possibility that left dislocation is still relevant for the case where the particle follows the PP.

| a. | Loop | naar de kerk. | |

| walk | to the church |

| b. | Mijn tante | woont [PP | daar dan naast]. | |

| my aunt | lives | there then next.to |

| b'. | [PP | Daar dan naast] | woont | mijn tante. | |

| [PP | there then next.to | lives | my aunt | ||

| 'Walk to the church. My aunt lives next to it.' | |||||

That we are simply dealing with a regular V2 structure in (51b') can be further supported by the fact that the constituent preceding the finite verb can also occur as the complement of a preposition or as the modifier of a noun phrase, as shown by the examples in (52); we gave the primeless examples a percentage sign, since we agree with the reviewer of Haegeman & Trotzke (2020) that such examples are strange in standard Dutch, but this does not affect the argument based on the primed examples.

| a. | % | Ik | heb | die lamp | gekocht [PP | voor [PP | dan naast die tafel]]. |

| I | have | that lamp | bought | for | then next.to that table | ||

| 'I bought that lamp for next to that table.' | |||||||

| a'. | Ik | heb | die lamp | gekocht [PP | voor [PP | daar dan naast]]. | |

| I | have | that lamp | bought | for | there then next.to |

| b. | % | [NP | De kamer [PP | dan naast de kopieerruimte ]] | is voor de PhD-studenten. |

| % | [NP | the room | then next.to the copy.room | is for the PhD-students | |

| 'The room next to the copy room is for the PhD students.' | |||||

| b'. | [NP | De kamer [PP | daar dan naast]] | is voor de PhD-studenten. | |

| [NP | the room | there then next.to | is for the PhD-students |

The fact illustrated in (50) that particles such as dan have a wider distribution than the conjunctive adverbs discussed earlier may thus be due to the fact that they can perform more that one syntactic function: the word-order variation in examples such as (50b) can then be explained by the hypothesis that dan cannot only be used as a conjunctive adverb, but also as a discourse particle of the same sort found in (51) and (52), which unambiguously are part of the PP. For both cases the putative V3-structures have been shown to not violate the V2-restriction.

| a. | Loop | naar het kerkplein. | |

| walk | to the church.square |

| b. | [PP | Dan | naast de kerk] | woont | mijn tante. | discourse particle | |

| [PP | then | next.to the church | lives | my aunt |

| b'. | [PP | naast de kerk]i | dan, daari | woont | mijn tante. | conjunctive adverb | |

| [PP | next.to the church | then there | lives | my aunt |

The two structures in the (b)-examples are both fully compatible with the V2-requirement, which is actually to be expected, given that conjunctive adverbs and discourse particles are not normally possible in sentence-initial position. The acceptability contrast between the (b)-examples shows that the non-temporal discourse reading is only easily available if dan is in the middle field of the clause: this alone make the derivation of examples such as (50) from (54b') by an additional movement of the PP naast de kerk quite implausible.

| a. | Loop | naar het kerkplein. | |

| walk | to the church.square |

| b. | Mijn tante | woont | dan | naast de kerk. | |

| my aunt | lives | then | next.to the church |

| b'. | ?? | Dan | woont | mijn tante | naast de kerk. |

| then | lives | my aunt | next.to the church |

This concludes our brief review of a selection of possible counterparts to the V2-restriction, showing that there is no conclusive evidence that this restriction can be violated. The most difficult case to crack were putative V3-structures of the kind in (47), which were ultimately analyzed as contrastive left-dislocation constructions with a conjunctive adverb functioning as a main-clause external discourse particle located between the left-dislocated element and the sentence. We have not discussed cases with focus particles such as Zelfs Jan was aanwezigEven Jan was present with the focus particle zelfseven; Section 13.3.2, sub IC, will show that such particles are also part of a larger phrase (here the subject).

This section has given a preliminary discussion of the formation of V1 and V2-clauses, and has shown that, as predicted, there are no examples of V3-clauses: all possible cases involve main-clause external material. Section 11.2 will continue the discussion with various subtypes of V1-clauses; the various subtypes of V2-clauses will be discussed in Section 11.3.