- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

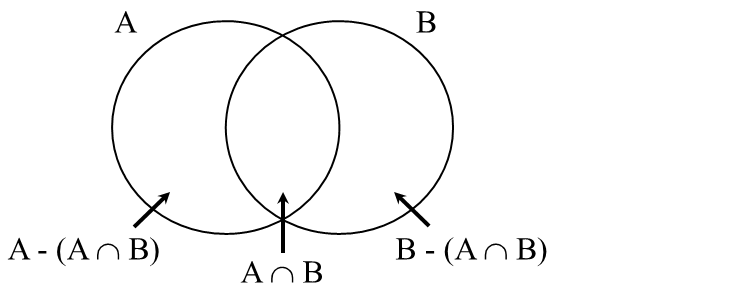

Section 18.1.1.1 has shown that the core meaning of the negative quantifier geen can be easily described using Figure 1, repeated from Section 14.1.2, sub IIA; its semantic contribution is usually to indicate that the intersection A ∩ B is empty. For instance, an example such as Er zwemmen geen ganzen in de vijverThere are no geese swimming in the pond expresses that the intersection of the set of geese and the set of entities swimming in the pond is empty.

The goal of the discussion in the following subsections is to examine whether this simple description does full justice to the intricacies involved in the semantics of constructions with geen. Subsection I examines the scope of negation expressed by geen, followed in Subsection II by a discussion of geen in (non-)specific and generic noun phrases. Subsection III concludes by showing that geen can exhibit special semantic properties that may be completely unrelated to its core meaning.

This subsection discusses the scope of the negation inherently expressed by geenno. Subsection A considers the most common situation in which geen unambiguously expresses sentence negation, i.e. it takes scope over the complete clause in which it occurs. Subsection B discusses cases of constituent negation, in which geen seems to take a more restricted scope, viz. over its own noun phrase. Subsection C goes on to show that the negation can also have scope over a subpart of the noun phrase with geen. Subsection D will show that geen, unlike sentential niet, cannot take any other constituent of the clause in its scope.

The core semantics of geen is that of negation, but although geen forms a syntactic constituent with the noun it precedes, the scope of negation is not necessarily limited to the noun phrase; in the vast majority of cases, the negation in geen takes sentential scope. This is particularly clear from the fact, illustrated in (239), that geen can license negative polarity items like ooitever and ook maar Xany X, because these can only be used in the presence of a structurally superior negative element; note that this holds regardless of whether the geen phrase is an argument, as geen autono car in (239a), or an adjunct, as geen momentno moment in (239b). That it is actually the presence of geen that licenses these negative polarity items is clear from the fact that geen does not alternate with een in (239), although this would be possible in the absence of the negative polarity items.

| a. | Ik | zou | geen/*een auto | ooit | aan | ook maar iemand | cadeau | geven. | |

| I | would | no/a car | ever | to | anyone | present | give | ||

| 'No car would I ever give to anyone as a present.' | |||||||||

| b. | Ik | zou | geen/*een moment | ook maar ergens | met hem | willen praten. | |

| I | would | no/a moment | anywhere | with him | want talk | ||

| 'At no time would I want to talk to him at any place.' | |||||||

The examples in (240) and (241) also support the conclusion that geen can take sentential scope. First, notice from the contrast in (240a&b) that the sentential negative adverb niet cannot occur in the clause-initial position; example (240b') shows that this is excluded even if niet is part of a topicalized participial verb phrase.

| a. | Ik | heb | die brief | niet | geschreven. | |

| I | have | that letter | not | written | ||

| 'I didnʼt write that letter.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Niet heb ik die brief geschreven. |

| b'. | * | [VP Niet geschreven] heb ik die brief. |

Crucial to our argument is that the unacceptability of (240b') shows that phrases containing sentence negation cannot be topicalized: since topicalization is usually possible in the case of constituent negation, the degraded status of (241b) supports the conclusion that the noun phrase geen brief expresses sentence negation.

| a. | Ik | heb | geen brief | geschreven. | |

| I | have | no letter | written | ||

| 'I didnʼt write a letter.' | |||||

| b. | * | [NP Geen brief] heb ik geschreven. |

This argument is somewhat weakened, however, by the fact that substituting the stronger form of negation geen enkelenot a single for geen results in full acceptability; we will discuss the latter in more detail in Subsection III. Strengthening the negation by adding an empathic accent to the preposed noun phrase may also improve the result, especially in more or less idiomatic expressions such as Geen letter heb ik geschreven!I have not written anything at all. However, in non-idiomatic examples such as (241b), emphatic stress usually leads to a constituent-negation reading; cf. Subsection B.

The fact that the negation takes scope outside the noun phrase may also account for the fact that noun phrases preceded by geen are usually plural when used as the subject of an expletive construction. Semantically, this makes sense, because sentence (242b) is simply the negation of sentence (242a), with a bare plural noun phrase triggering plural agreement: ¬(er lopen kinderen op straat).

| a. | Er | lopen | kinderen | op straat. | |

| there | walk | children | in the.street | ||

| 'There are children walking in the street.' | |||||

| b. | Er lopen geen | kinderen | op straat. | |

| there walk no children | in | the.street | ||

| 'There are no children walking in the street.' | ||||

Note that the examples in (243) show that geen can also occur in singular subjects, but in this case it is not used as sentence negation. Example (243b) is either used in discourse as an explicit denial of the proposition expressed by (243a) or it receives the stronger “not a single” reading; cf. Section 18.1.1.1 and Subsection III for further discussion.

| a. | Er | loopt | een kind | op straat. | |

| there | walks | a child | in the street | ||

| 'There is a child walking in the street.' | |||||

| b. | Er | loopt | geen kind | op straat. | |

| there | walks | no child in | the.street | ||

| Proposition denial: 'No, It is not true that a child is walking in the street.' | |||||

| “Not a single” reading: 'There isn't a single child walking in the street.' | |||||

In contrastive contexts, geen can be used as a constituent negator. If the noun phrase is singular, it usually alternates with niet een, as in (244a), but if the noun phrase is plural, the use of geen is the only option, as in (244).

| a. | Er | is geen/niet een brief | gekomen | maar | een pakje. | singular noun | |

| there | is no/not a letter | come | but | a parcel | |||

| 'There came not a letter but a parcel.' | |||||||

| b. | Er | zijn | geen brieven | gekomen | maar | een pakje. | plural noun | |

| there | are | no letters | come | but | a parcel |

| b'. | * | Er | zijn | niet | Ø/een | brieven | gekomen | maar | een pakje. |

| there | are | not | Ø/a | letters | come | but | a parcel |

Topicalization of a geen phrase expressing constituent negation, as in (245a), is at least marginally possible, and seems to lead to a better result than topicalization of the negative adverb niet and its associate noun phrase.

| a. | (?) | Geen brief | heb | ik | geschreven | maar | een memo. |

| no letter | have | I | written | but | a memo | ||

| 'I wrote not a letter but a memo.' | |||||||

| b. | ? | Niet een brief | heb | ik | geschreven | maar | een memo. |

| not a letter | have | I | written | but | a memo |

The use of geen in contrastive contexts is excluded when the noun phrase functions as the complement of a PP. In fact, Haeseryn et al. (1997:1657) found that geen-phrases only occur as complements of PPs in idiomatic constructions: Dat ongeluk was met geen pen te beschrijvenThat accident was horrendous. We refer the reader to Section 18.1.5.3 for further discussion.

| a. | Dat | moet | je | niet | met een kwast | verven, | maar | met een roller. | |

| that | must | you | not | with a brush | paint | but | with a roller | ||

| 'You should not paint that with a brush, but with a roller.' | |||||||||

| b. | * | Dat | moet | je | met geen kwast | verven, | maar | met een roller. |

| that | must | you | with no brush | paint | but | with a roller |

It is crucial that, outside of contrastive contexts such as (244), replacing geen with niet een is in most cases impossible; in a neutral sentence such as (247), it would definitely be odd to use niet een instead of geen. This again shows that geen cannot systematically be treated as a fusion of niet and the indefinite article een, since this would lead to the incorrect expectation that the infelicity of (247) with niet een would be preserved if niet and een were fused into geen.

| Er | is geen/#niet een brief | gekomen. | ||

| there | is no/not a letter | come | ||

| 'There didnʼt come any letter.' | ||||

An alternative to the fusion approach is to assume that geen is simply lexically marked as a sentence negation, while niet should not be analyzed as a sentence negation when immediately followed by an indefinite noun phrase. Section V13.3.2, sub IC, claims that in such cases niet behaves as a focus particle comparable in several respects to ookalso and alleenonly. The meaning attributed to such particles is that they modify a presupposed proposition in the ways indicated in Table 4 (after Dik 1997a), where the exclamation mark indicates contrastive accent.

| (PA)S | modified set PS | expression type | |

| correcting | X | Y | not X, but Y! |

| expanding | X | X and Y | also Y! |

| restricting | X and Y | X | only X! |

| selecting | X or Y | X | X! |

The additional notion of correction of an earlier proposition immediately explains the contrast in acceptability in neutral sentences such as (247), and it seems quite appropriate for describing the subtle meaning difference between the use of geen and niet een in (244a), repeated here in a slightly different form as (248); (248a) simply asserts that of two conceivable eventualities, only one is actualized, while example (248b) corrects an earlier presupposition by saying that the actualized event did not involve the arrival of a letter, but the arrival of a parcel.

| a. | Er | is geen brief | gekomen | maar | een pakje. | |

| there | is no letter | come | but | a parcel | ||

| 'There came not a letter but a parcel.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | is niet een brief | gekomen | maar | een pakje. | |

| there | is not a letter | come | but | a parcel | ||

| 'There came not a letter but a parcel.' | ||||||

The difference in meaning between the two examples in (248) strongly suggests that geen simply expresses sentence negation, and that the constituent-negation reading of (248a) is an epiphenomenon resulting from the focus assignment to the head noun; the only genuine case of constituent negation is given in (248b). The additional claim that the constituent negator niet in (248b) is a focus particle also explains the contrast between the two examples in (246), since (249a) shows that the focus particle alleen must also precede the full PP. Furthermore, example (249b) shows that pied piping of alleen under topicalization is only marginally possible, just like pied piping of niet in (245b).

| a. | Dat | moet | je | alleen | met een kwast | verven, | niet met een roller. | |

| that | must | you | only | with a brush | paint | not with a roller | ||

| 'You should only paint that with a brush, not with a roller.' | ||||||||

| b. | ? | Alleen een brief | heb | ik | geschreven, | niet een memo. |

| only not a letter | have | I | written | not a memo | ||

| 'I only wrote a letter, not a memo.' | ||||||

To conclude this subsection, we note that Haeseryn et al. (1997:1658) also propose a fusion analysis for negative quantifiers/adverbs like niemand, niets, nergens. However, they also note that these forms differ from geen in that the positive form immediately preceded by niet and the negative form are normally in complementary distribution. In neutral sentences like those in (250), it is usually the negative quantifier/adverb that is used. This follows from our earlier proposal that niet is a focus particle that can only be used in the counter-presuppositional context of correction.

| a. | Er | is niemand/*niet iemand | gekomen. | |

| there | is nobody/not somebody | come | ||

| 'Nobody came.' | ||||

| b. | Er | is niets/*niet iets | misgegaan. | |

| there | is nothing/not something | wrong.gone | ||

| 'Nothing has gone wrong.' | ||||

| c. | Er | is nergens/*niet ergens | corruptie | gepleegd. | |

| there | is nowhere/ not somewhere | corruption | committed | ||

| 'Corruption was committed nowhere.' | |||||

| d. | Er | is nooit/*niet ooit | corruptie | gepleegd. | |

| there | is not once/never | corruption | committed | ||

| 'There has never been corruption.' | |||||

In contrastive sentences like those in (251), on the other hand, the form with niet is generally used. This would follow if we assume that, unlike noun phrases of the form geen + N, negative quantifiers/adverbs cannot be used in contrastive contexts. This difference is probably related to the fact that the contrast always involves the nominal head of the phrase geen N, since the quantificational part of the quantifiers/adverbs may be semantically too weak to express contrast.

| a. | Er | is niet iemand/*niemand | gekomen | maar | iedereen. | |

| there | is not somebody/nobody | come | but | everyone | ||

| 'Not somebody came but everybody.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | is niet iets/*niets | misgegaan | maar | alles. | |

| there | is not something/nothing | wrong.gone | but | everything | ||

| 'Not something but everything has gone wrong.' | ||||||

| c. | Er | is niet ergens/*nergens | corruptie | gepleegd | maar | overal. | |

| there | is not somewhere/nowhere | corruption | committed | but | everywhere | ||

| 'Not somewhere but everywhere there was corruption committed.' | |||||||

| d. | Er | is niet ooit/*nooit | corruptie | gepleegd | maar | altijd. | |

| there | is not once/never | corruption | committed | but | always | ||

| 'Not once but always there has been corruption.' | |||||||

We conclude that empirical evidence suggests that the fusion analysis of negative quantifiers/adverbs should also be abandoned.

Subsection B suggested that the constituent-negation reading of cases with geen results from the interaction of sentence negation and focus assignment to the head noun. This type of analysis predicts that the scope reduction of the sentence negation expressed by geen need not stop at the border of the noun phrase with geen. Indeed, this is what we find; the scope of the sentence negation expressed by geen can be further reduced to e.g. an attributive modifier within the noun phrase. An ambiguous example of this type is given in (252a), together with its semantically more transparent alternates with niet in the (b)-examples; (252b) has only a reading where niet negates the adjective geringe, while (252b') has only a reading where niet negates the entire noun phrase.

| a. | Dat | is | geen geringe prestatie. | |

| that | is | no insignificant accomplishment |

| b. | Dat | is | een | niet geringe | prestatie. | |

| that | is | a | not insignificant | accomplishment |

| b'. | Dat | is | niet een geringe prestatie. | |

| that | is | not an insignificant accomplishment |

Ambiguity of a similar kind to that in (252a) can be found in noun phrases of the type illustrated in (253a), whose ambiguity comes out in the paraphrases in the (b) examples. Depending on the precise analysis of the internal structure of noun phrases of the type professor Van Riemsdijk (cf. 17.1.3), either (253b) or (253b') instantiates a case in which geen takes scope over a subpart of the noun phrase in which it occurs.

| a. | Ik | ken | geen professor | Van Riemsdijk. | |

| I | know | no professor | Van Riemsdijk |

| b. | Ik | ken | [geen Van Riemsdijk] | die | professor is. | |

| I | know | no Van Riemsdijk | that | professor is |

| b'. | Ik | ken | [geen professor] | die | Van Riemsdijk | heet. | |

| I | know | no professor | that | Van Riemsdijk | is.called |

We conclude this subsection with two remarks. First, it should be noted that the ambiguity of (252a) and (253a) exists only on paper, since the intonation will provide clues as to the intended reading. Second, if one were to treat geen in (252a) as the fusion of niet and the indefinite article een, one would have to assume that the order of niet and een is irrelevant; both een niet in (252b) and niet een in (252b') should be able to “fuse” into geen.

Although Subsection C has shown that the scope of the sentence negation expressed by geen can be reduced to elements with which it does not form a constituent, such syntax/semantics mismatches are certainly not possible in just any context. To see this, first observe that the negative adverb niet in (254a) can be construed semantically with the manner adverb goedwell, even though it does not form a constituent with it, which is clear from the fact that it must be stranded under topicalization. In (254b), on the other hand, the negation expressed by the negative quantifier geen cannot be associated with the adverbial phrase; the sentence is at best marginally acceptable on a highly marked count-noun reading of hitte, as in Ik verdraag geen enkele ?(soort) hitte goed I cannot stand any (kind of) heat.

| a. | Ik | verdraag | hitte | niet (goed). | |

| I | bear | heat | not well |

| a'. | * | Niet goed verdraag ik hitte. |

| a''. | Goed verdraag ik hitte niet. |

| b. | * | Ik | verdraag | geen hitte | goed. |

| I | bear | no heat | well |

We conclude from this that the scope reduction of the sentence negation expressed by geen is not free, but tied to its noun phrase containing geen in the sense that the negation cannot be semantically associated with other constituents of the clause.

Haeseryn et al. (1997: §29.4) suggest that the negative article geenno is formed by the fusion of the negative adverb niet not and the indefinite article. This subsection has argued on empirical grounds that this analysis cannot be sustained; geen is simply a lexical form (probably not even an article, but a numeral or quantifier) that inherently expresses sentence negation. The fact that geen N sometimes seems to receive a constituent-negation reading similar to that expressed by sequences of the form niet [een N] is not an inherent property of geen, but of the construction in which it is used; in particular, contrastive focus may result in a reduction in the scope of the sentence negation expressed by geen.

Noun phrases with geen pattern syntactically with indefinite noun phrases. This is clear, for example, from the fact illustrated in (255a) that subjects with geen must occur with the expletive er; apart from example (255a'), which is acceptable on the special “not a single” reading to be discussed in Subsection IIIA, all primed examples are degraded. Note that this is not due to the restriction on topicalization discussed in Subsection IA, since subjects need not be topics; cf. Section 21.1.2, sub II.

| a. | Er | is waarschijnlijk | geen brief | verstuurd | vandaag. | |

| there | is probably | no letter | sent | today | ||

| 'Probably no letter is sent today.' | ||||||

| a'. | # | Geen brief is waarschijnlijk verstuurd vandaag. |

| b. | Er | spelen | waarschijnlijk | geen kinderen | op straat. | |

| there | play | probably | no children | in the.street | ||

| 'There are probably no children playing in the street.' | ||||||

| b'. | * | Geen kinderen spelen waarschijnlijk op straat. |

| c. | Er | staat | waarschijnlijk | geen melk | in de ijskast. | |

| there | stands | probably | no milk | in the fridge | ||

| 'There is probably no milk in the fridge.' | ||||||

| c'. | * | Geen melk stond waarschijnlijk in de ijskast.’ |

Another finding in support of the indefiniteness of noun phrases with geen is that they are not easily scrambled across certain adverbials; cf. Section 21.1.4, sub IC. This is illustrated by the degraded status of the scrambled counterparts of the primeless examples in (255) in (256); the percentage signs indicate that speakers’ judgments vary from marked to completely unacceptable.

| a. | % | Er is geen brief waarschijnlijk verstuurd vandaag. |

| b. | % | Er spelen geen kinderen waarschijnlijk op straat. |

| c. | % | Er staat geen melk waarschijnlijk in de ijskast. |

It seems that noun phrases with geen behave like indefinites even in generic contexts. To see this, consider the generic constructions in (257). Example (257a) shows that the generic plural noun phrase must be scrambled to a position preceding the clause adverbial waarschijnlijkprobably; cf. Section 21.1.4, sub IC. The noun phrase with geen in (257b), on the other hand, cannot be placed to the left of waarschijnlijk.

| a. | Hij | begrijpt | < formules> | waarschijnlijk <*formules> | niet. | |

| he | understands | formulae | probably | not | ||

| 'He probably doesnʼt understand formulae.' | ||||||

| b. | Hij | begrijpt | <*geen formules> | waarschijnlijk <geen formules>. | |

| he | understands | no formulae | probably | ||

| 'He probably doesnʼt understand formulae.' | |||||

Note that negative sentences with generic noun phrases sometimes exhibit intriguing semantic differences between the variants with niet and their counterparts with geen. For instance, example (258a) allows for two different lexical meanings of accepterento accept; either the speaker does not wish to receive charity, or he is opposed to the existence of charity as a phenomenon. The latter reading is conspicuously more prominent in (258b).

| a. | Ik | accepteer | geen liefdadigheid. | |

| I | accept | no charity |

| b. | Ik | accepteer | liefdadigheid | niet. | |

| I | accept | charity | not |

Subsections I and II discussed the core semantics of the negative quantifier geen. This subsection deals with a number of more or less specialized meaning contributions of geen. We will start our discussion with the “not a single” reading, which stays close to the core semantics of negative quantification, but we will see that there are contexts in which the semantic contribution of geen can deviate substantially from the core meaning; sometimes negative quantification is even absent in some uses of geen.

The negative quantifier geen sometimes expresses a meaning stronger than simple negation, which we will refer to as the “not a single” reading; cf. Klooster (2001b:57). This reading requires that geen be followed by some contrastively accented element, and can sometimes be strengthened by the addition of certain elements, such as the modifier enkelsingle or the cardinal numeral éénone.

| Geen | (enkel/één) | schip | is 100% waterdicht. | ||

| no | single/one | ship | is 100% watertight | ||

| 'Not a single ship is 100 percent watertight.' | |||||

Given the meaning expressed, it is not surprising that the head noun in the “not a single” reading is usually a singular count noun; cf. Postma (1999). However, Hoeksema (2013) correctly points out that there are some cases where geen enkele is followed by a non-count noun, as in (260).

| a. | Jan heeft | geen | enkele | spijt/angst/pijn. | |

| Jan has | no | single | regret/fear/pain | ||

| 'Jan has no regret/fear/pain whatsoever.' | |||||

Hoeksema also notes that cases with a plural noun, such as zorgen in (261a), are also possible. He suggests that this may be the result of an ongoing change, but it is not obvious that this is indeed the case because zich zorgen makento worry is a fixed collocation which does not allow the singular form zorg; cf. *zich zorg maken. Since the more or less synonymous construction in (261b) is clearly degraded with the plural noun problemenproblems, we conclude that there is no reason to assume that the noun can be plural in the normal case, although we have to add that occasional cases of this form can be found on the internet.

| a. | Jan maakt | zich | geen (enkele) | zorgen/*zorg. | |

| Jan makes | refl | no single | worries/worry | ||

| 'Jan does not worry at all.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | geen enkel probleem/*geen enkele problemen. | |

| Jan has | no single problem/no single problems | ||

| 'Jan has not a single problem.' | |||

The use and distribution of “not a single” phrases with geenno, geen enkelenot a single, and geen éénnot one differ in subtle ways. We start with the “not a single” reading of noun phrases with geen. This reading is common for noun phrases with geen in subject position, as in (262a); all subjects with geen in regular object position (i.e. in non-expletive constructions) are of this type. Objects with geen can also receive this interpretation, and for topicalized objects this reading is in fact the only one available; cf. the discussion of (241).

| a. | Geen schip | is 100% waterdicht. | |

| no ship | is 100% watertight | ||

| 'Not a single ship is 100 percent watertight.' | |||

| b. | ? | Geen schip | levert | men | 100% waterdicht | af. |

| no ship | delivers | one | 100% watertight | prt. | ||

| 'Not a single ship is 100 percent watertight at the point of delivery.' | ||||||

Prosodically, the “not a single” reading of geen phrases is immediately recognizable by the fact that there is main stress on the element immediately following geen. This is often the head noun, but when an attributive adjective is present, it is usually the adjective that receives the greatest prominence.

| a. | [geen schip] is 100% waterdicht |

| b. | [geen nieuw schip] is 100% waterdicht |

As in the more usual cases, geen takes scope outside the noun phrase, as can be seen from the fact that it can license negative polarity items such as ooitever; cf. Subsection IA. This is illustrated in (264) for a subject and a topicalized object. We will see, however, that the sentence negation expressed by geen can also receive a reduced-scope reading, in which negation is construed with the accented element following geen.

| a. | Geen computerprogramma | is ooit | volledig | storingsvrij. | |

| no computer.program | is ever | completely | error.free |

| b. | ? | Geen computerprogramma | heeft | dit bedrijf | ooit | storingsvrij | afgeleverd. |

| no computer.program | has | this company | ever | error.free | delivered |

The “not a single” reading of geen phrases is also common for subjects of comparative constructions.

| a. | Geen schip | vaart | sneller | naar Engeland | dan | het onze. | |

| no ship | sails | faster | to England | than | ours |

| b. | Geen limonade | smaakt | lekkerder | dan | deze. | |

| no lemonade | tastes | nicer | than | this.one |

Within this class of constructions, however, a distinction should be made between comparatives such as in (265), where particular makes or brands of the same type of product are compared, and those such as in (266), where two different types of product are compared. In contrast to the primeless examples, the primed examples in (266) sound distinctly odd.

| a. | Een schip | vaart | sneller | dan een luchtballon. | |

| a ship | sails | faster | than a hot.air.balloon |

| a'. | ?? | Geen schip | vaart | sneller | dan een luchtballon. |

| no ship | sails | faster | than a hot.air.balloon |

| b. | Limonade | smaakt | lekkerder | dan | versgeperst | sinaasappelsap. | |

| lemonade | tastes | nicer | than | freshly.squeezed | orange.juice |

| b'. | ?? | Geen limonade | smaakt | lekkerder | dan | versgeperst | sinaasappelsap. |

| no lemonade | tastes | nicer | than | freshly.squeezed | orange.juice |

The assertions that the primed examples in (266) intend to express can be expressed by adding the modifier enkel(e)single, as in (267a&b). In accordance with the generalization that the main stress must be assigned to the element following geen, the main prosodic prominence is assigned to the modifier: geen enkel(e) N.

| a. | Geen enkel schip | vaart | sneller | dan een luchtballon. | |

| no single ship | sails | faster | than a hot.air.balloon |

| b. | Geen enkele limonade | smaakt | lekkerder | dan versgeperst sinaasappelsap. | |

| no single lemonade | tastes | nicer | than freshly.squeezed orange.juice |

The modifier enkele can also be used in contexts where reference is made to specific entities (or rather the absence of them). In (267) and (268), the sentence negation expressed by geen clearly receives a reduced-scope reading, since it must be construed with the contrastively focused modifier enkel(e)single; thus, the effect of adding the modifier is that the “not a single” reading is expressed in a more transparent and explicit way.

| a. | Hij heeft | geen enkele fout | gemaakt. | |

| he has | no single mistake | made | ||

| 'He didnʼt make a single mistake.' | ||||

| b. | Ik heb | geen enkel boek | verkocht. | |

| I have | no single book | sold | ||

| 'I havenʼt sold a single book.' | ||||

The reduced-scope reading may also explain why geen enkele N phrases differ from ordinary geen N phrases in that they cannot be used as predicates in complementive constructions, as shown in (269): in (269a), geen has sentential scope and can therefore simply express that Jan does not have the property of being a soldier, but the reduced-scope reading found with geen enkele makes this impossible.

| a. | Jan is geen soldaat. | |

| Jan is no soldier | ||

| 'Jan is not a soldier.' |

| b. | * | Jan is geen enkele soldaat. |

| Jan is no single soldier |

The “not a single” reading can also be emphasized by adding the element één, as in the examples in (270). Here, too, the sentence negation expressed by geen has a clearly reduced scope, since it must be construed with the contrastively focused numeral éénone. The reduced-scope reading is further supported by the fact that één cannot replace enkele in example (269b); cf. *Jan is geen één soldaat.

| a. | Hij | heeft | geen | één fout | gemaakt. | |

| he | has | no | one mistake | made | ||

| 'He didnʼt make a single mistake.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | heb | geen | één boek | verkocht. | |

| I | have | no | one book | sold | ||

| 'I havenʼt sold a single book.' | ||||||

Observe that the examples in (270) alternate with the constructions in (271) with the focus particle niet in the examples, which is also construed with the contrastively accented numeral één.

| a. | Hij | heeft | niet | één fout | gemaakt. | |

| he | has | not | one mistake | made |

| b. | Ik | heb | niet | één boek | verkocht. | |

| I | have | not | one book | sold |

The “not a single” interpretation of geen is the one normally found in the numerous idiomatic negative polarity constructions with geen phrases. The idiomatic noun phrases in (272) have the prosody characteristic of the “not a single” cases discussed above: the main accent is assigned to the element following geen. The primed examples show that the idiomatic examples behave like the non-idiomatic ones in allowing topicalization. For a recent corpus study to cases of this kind, see Van den Heede & Lauwers (2024).

| a. | Hij | heeft | er | geen | jota/moer | van | begrepen. | |

| he | has | there | no | iota/nut | of | understood | ||

| 'He didnʼt understand a word of it.' | ||||||||

| a'. | Geen jota/moer heeft hij ervan begrepen. |

| b. | Hij | heeft | geen | vinger/hand/poot | uitgestoken. | |

| he | has | no | finger/hand/leg | stuck.out | ||

| 'He didnʼt lift a finger.' | ||||||

| b'. | Geen vinger/hand/poot heeft hij uitgestoken. |

| c. | Hij | vertrouwt | haar | voor geen cent/meter. | |

| He | trusts | her | for no cent/meter | ||

| 'He doesn't trust her one bit/at all.' | |||||

| c'. | Voor geen cent/meter vertrouwt hij haar. |

The addition of enkel(e)single and éénone is impossible in these idiomatic examples; however, geen can often be intensified by the addition of accented schwa-inflected eneone, as in (273a). In contrast, geen ene cannot easily be used in non-idiomatic examples such as (273b); the uninflected form één or the modifier enkel(e) is highly preferred in this case.

| a. | Hij | heeft | er | geen | ene/*enkele/*één | jota/moer | van | begrepen. | |

| he | has | there | no | one/single/one | iota/nut | of | understood |

| b. | Hij | heeft | geen | enkele/één/??ene | vraag | begrepen. | |

| he | has | no | single/one/one | question | understood | ||

| 'He didnʼt understand a single question.' | |||||||

That we are dealing with negative polarity phrases is clear from the fact that the nominal phrase geen (ene) jota/moer can only be replaced by its positive counterpart without geen when the negation is expressed by some other (c-commanding) negative constituent in its minimal clause, as illustrated in (274), which is only acceptable with the negative subject niemand.

| a. | Niemand/*Hij | heeft | er | (ene) jota/moer | van | begrepen. | |

| nobody/he | has | there | one iota/nut | of | understood | ||

| 'Nobody understood a word of it.' | |||||||

The geen-phrases with a “not a single” reading discussed in this subsection are characterized by the fact that they are headed by a singular count noun and contain a contrastive accent. They differ from neutrally accented geen-phrases in that they can occur as the complement of a preposition, as shown by the contrast between the two unprimed and primed examples in (376), taken from Klooster (2001b: §6).

| a. | Je | moet niet | op meevallers | rekenen. | |

| you | must not | on strokes.of.luck | count | ||

| 'You shouldn't count on windfalls.' | |||||

| a'. | * | Je | moet | op geen meevallers | rekenen. |

| you | must | no strokes.of.luck | count |

| b. | Marie was niet | verliefd | op een Spanjaard. | |

| Marie was not | in.love | with a Spaniard | ||

| 'Marie was not in love with a Spaniard.' | ||||

| b'. | * | Marie was | op geen Spanjaard | verliefd |

| Marie was | with no Spaniard | in love |

| c. | Jan werkt | niet | in een stad. | |

| Jan works | not | in a city | ||

| 'Jan does not work in a city.' | ||||

| c'. | * | Jan werkt | in geen stad. |

| Jan works | in no city |

We will not discuss Klooster’s syntactic analysis of the contrast between regular geen-phrases and geen-phrases with a “not a single”, but only note that it is built on two premises: (i) negative noun phrases cannot be directly selected by prepositions (this is ruled out by a filter *P DP[+Neg]); this restriction is lifted when the noun phrase is focused (indicated by the obligatory accent found in the earlier examples). If these premises are correct, they would also account for the acceptability of the examples in (276), in which we find a “not even” reading.

| a. | Ik | zou | dat voor geen goud | willen | doen. | |

| I | would | that for no gold | want | do | ||

| 'I wouldnʼt want do that, not even for gold.' | ||||||

| b. | Dat | verkoop | je | in geen honderd jaar.’ | |

| that | sell you | in | no hunderd year | ||

| 'You wouldn't sell that, not even in a hundred years.' | |||||

For completeness’ sake, Klooster notes that pronouns such as niemandnobody can be used in PPs because they are always focused in such cases: dat Marie op niemand wil wachten that Marie doesn't want to wait for anyone.

A number of constructions with geen exhibit so-called negative concord, i.e. the multiple occurrence of negative elements with a single negative interpretation as their combined effect; unlike in cases of double negation, there is no cancellation of the negation. These constructions occur only in the spoken language, and some of them may not be part of the standard variety.

A case that probably belongs to standard spoken Dutch is illustrated in (277a). Here geen itself is the negator; it is modified by the negative pronoun niks (the colloquial variant of niets, which seems impossible here). The addition of niks to geen has the effect of intensifying the negation, comparable to what English at all achieves in the translation. An alternative (and more prestigious) way of realizing this intensification is with the help of helemaal in (277b); cf. Section 20.2.

| a. | Dat | was | niks/*?niets | geen leuke tijd. | |

| that | was | nothing/nothing | no nice time | ||

| 'That was not a particularly nice time at all.' | |||||

| b. | Dat | was helemaal | geen leuke tijd. | |

| that | was altogether | no nice time |

A very popular case of negative concord in non-standard spoken language is given in example (278a). In current normative grammars and style books, the appreciation of this construction varies. Some claim that the two negations always cancel each other out in standard Dutch, and therefore disapprove and/or discourage the use of (278a) in the negative concord reading, and strongly favor the use of the unambiguous construction in (278b). Others, on the other hand, regard the use of negative concord as a normal way of emphasizing negation; cf. taaladvies.net/taal/advies/vraag/584 for relevant citations.

| a. | Ik | gebruik | nooit | geen zout. | |

| I | use | never | no salt | ||

| Double negation reading: 'I never use no salt.' | |||||

| Negative concord reading: 'I never use any salt.' | |||||

| b. | Ik | gebruik | nooit | zout. | |

| I | use | never | salt | ||

| 'I never use (any) salt.' | |||||

The two readings of (278a) are associated with different intonation patterns. The double negation reading is obtained by assigning stress peaks to both nooit and (especially) geen, as in (279a). In the case of negative concord, on the other hand, there is no significant accent on geen, and nooit only receives heavy accent when it is used contrastively, as in (279b).

| a. | Double negation reading: Ik gebruik nooit geen zout. |

| b. | Negative concord reading: Ik gebruik nooit/nooit geen zout. |

Further illustrations of the negative concord construction are given in (280a), all adapted from actual examples on the internet. Examples (280b-d) show that negative concord is also possible for negative elements other than geen, although nooit geen seems to be by far the most common case of negative concord.

| a. | Ik | heb | nooit | geen zin | in seks. | |

| I | have | never | no liking | in sex | ||

| 'I never feel like having sex.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | ga nooit | niet | meer | in de achtbaan. | |

| I | go never | not | anymore | in the roller.coaster | ||

| 'I will never go in the roller coaster anymore.' | ||||||

| c. | Hij | heeft | nooit | niks | om PRO | me gegeven. | |

| he | has | never | nothing | comp | me cared | ||

| 'He never cared about me.' | |||||||

| d. | Chatten is leuk, | maar | er | is | bijna | nooit | niemand. | |

| chatting is nice | but | there | is | nearly | never | no.one | ||

| 'Chatting is nice, but there is virtually never someone there.' | ||||||||

A third context in which geen occurs in a negative-concord environment is the non-standard exclamative construction in (281a), in which geen occurs twice; once as the negative quantifier of the noun phrase in object position, and once as a subpart of the formally negative element geeneensnot even. The second occurrence is probably a spurious use of geen: it alternates with the more generally accepted form in (281b), where the noun phrase is non-negative, so that the negation must be expressed by geeneens. Another way of expressing (281a) is given in (281c), where the negation is expressed by niet eensnot even. The numbers to the right of the examples in (281) indicate the number of hits that resulted from a Google search (June 10, 2020) on search strings consisting of the finite verb heb followed by the italicized parts in (281).

| a. | ... en | ik | heb | (nog) | geeneens | geen auto! | 30 |

| b. | ... en | ik | heb | (nog) | geeneens | een auto! | 160 |

| c. | ... en | ik | heb | (nog) | niet eens | een auto! | 140 | |

| ... and | I | have | still | not even | a car | |||

| '... and I donʼt even have a car at all (yet)!' | ||||||||

The use of geen can invoke evaluative semantics on noun phrases that are otherwise not evaluative in nature, as illustrated in (282a&b). The negation of levenlife by geen leads to an interpretation according to which an emphatically negative evaluation is attributed to life, alternatively expressible by combinations of an adjective and a noun (either compound or phrasal), as in the primed examples.

| a. | Dat | is | toch | geen leven! | |

| that | is | prt | no life |

| a'. | een | rotleven | compound | |

| a | rotten.life |

| b. | Zo | heb | je | toch | geen leven! | |

| so | have | you | prt | no life |

| b'. | een | vreselijk | leven | phrasal | |

| a | terrible | life |

Geen phrases of this kind only occur in predicative position or as the complement of hebbento have. This is illustrated by the examples in (283): while (283a&b) have an evaluative interpretation, this is not the case in (283c).

| a. | Ik | vind | dit | geen weer! | complementive | |

| I | consider | this | no weather | |||

| 'I consider this horrible weather' | ||||||

| b. | We | hebben | weer eens | geen weer! | complement of hebben | |

| we | have | again once | no weather | |||

| 'We are having horrible weather once more.' | ||||||

| c. | # | Ze | voorspellen | geen weer! | argument position |

| they | forecast | no weather |

Some idiomatic examples can be found in (284). Example (284b) differs from the previous examples in that it involves a positive evaluation: the combination of geen and the substance noun functions as an idiomatic expression meaning “not a small thing, quite something”. Such cases are quite close to litotes, i.e. cases in which the negation is used to emphatically express the opposite of what is expressed by the negated element; cf. Dat is niet niksThis is quite something.

| a. | Dat | is geen gezicht/porum! | |

| that | is no sight | ||

| 'That looks ugly, terrible.' | |||

| b. | Dat | is geen | kattenpis. | |

| that | is no | cat.pee | ||

| 'That's not chicken feed!' | ||||

Measure phrases of time and distance, like tien minutenten minutes in (285a) and tien kilometerten kilometers in (285b), can be combined with geen to yield an interpretation that can be paraphrased as “less than X”. The adverbial element nog is typically present alongside geen in such cases, though it seems that it is not strictly necessary in all cases; while in (285a) it would be awkward to omit nog, in (285b) it does not seem completely impossible.

| a. | Na nog geen tien minuten | brak | de hel | los. | |

| after yet no ten minutes | broke | the hell | loose | ||

| 'After less than ten minutes, all hell broke loose.' | |||||

| b. | Die boerderij | ligt | nog geen tien kilometer | van het stadscentrum. | |

| that farmhouse | lies | yet no ten kilometers | from the town center | ||

| 'That farmhouse is less than ten kilometers away from the town center.' | |||||

An interpretively somewhat different case of the same type is given in (286) from the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (item geen). Here the combination of geen and the numeral duizend has an interpretation that can be paraphrased as “not even a thousand”.

| Simson | deed | voor geen duizend Filistijnen | onder. | ||

| Simson | did | for no thousand Philistines | under | ||

| 'Samson was not inferior even to a thousand Philistines.' | |||||

In many of the examples in the previous subsections, the core meaning of geen as a negative quantifier seems to be lost. A particularly striking illustration of this fact is provided by examples of the type in (287), where the accent does not fall on geen.

| a. | Zijn | dat | geen courgettes? | |

| are | that | no zucchinis | ||

| 'Those are zucchinis, arenʼt they?' | ||||

| b. | Is | dat | geen leuk idee? | |

| is | that | no nice idea | ||

| 'That is a nice idea, isnʼt it?' | ||||

That these are not negative questions is evident from the fact that the speaker who asks a question of the type in (287a) anticipates a positive answer. This is explicitly acknowledged in the answer in (288a) by the addition of the adverb inderdaadindeed. A negative answer is of course possible, but not anticipated by the speaker, which is clear from the fact that the inclusion of the adverb inderdaad in the response in (288b) is pragmatically awkward.

| a. | Ja, | dat | zijn | inderdaad | courgettes. | |

| yes | that | are | indeed | zucchinis |

| b. | Nee, | dat | zijn | (#inderdaad) | geen courgettes. | |

| no | that | are | indeed | no zucchinis |

Note, however, that the answer in (288b) with inderdaad is only out of place as a response to (287a) if this question is assigned the prosodic contour typical for questions of this type, with the main accent on courgettes followed by an acutely rising intonation; there is also a truly negative interpretation for (287a), in which geen receives heavy accent, for which (288b) with inderdaad does count as a pragmatically felicitous response.

On the intended, non-negative interpretation of the examples in (287), geen seems dispensable; the examples in (289) can be used in the same contexts as non-negative (287), and are equally acceptable/felicitous. The main difference seems to be that the speaker does not anticipate a positive answer to his question.

| a. | Zijn | dat | courgettes? | |

| are | that | zucchinis |

| b. | Is | dat | een leuk idee? | |

| is | that | a nice idea |

We conclude this subsection by pointing out that the negative adverb niet exhibits the same behavior as geen in that it can appear in non-negative questions. In (289), the negative adverb niet can be added to the immediate right of dat with preservation of meaning: Zijn dat niet courgettes? or Is dat niet een leuk idee?