- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section discusses alternations between accusative objects and PPs with various functions. Subsection I begins with a brief discussion of the alternation between accusative phrases and complement PPs of the type in (455), where the form of the verb remains constant.

| a. | Jan schopte | zijn hond. | |

| Jan kicked | his dog. |

| a'. | Jan schopte | naar zijn hond. | |

| Jan kicked | at his dog |

| b. | Jan bouwde | een schip. | |

| Jan built | a ship |

| b'. | Jan bouwde | aan een schip. | |

| Jan built | at a ship |

| c. | Jan at | de cake. | |||

| Jan ate | the cake | ||||

| 'Jan ate the cake.' | |||||

| c'. | Jan at | van de cake. | |||

| Jan ate | from the cake | ||||

| 'Jan ate of the cake.' | |||||

Standard Dutch accusative/PP alternations often go hand in hand with prefixation of the verb with be-, ver-, and ont-, as in (456).

| a. | Jan kijkt naar Marie. | |||

| Jan looks at Marie | ||||

| 'Jan is looking at Marie.' | ||||

| a'. | Jan bekijkt | Marie. | ||

| Jan be-looks | Marie | |||

| 'Jan is examining Marie.' | ||||

| b. | Peter zorgt | voor de paarden. | |||

| Peter looks | after the horses | ||||

| 'Peter takes care of the horses.' | |||||

| b'. | Peter verzorgt | de paarden. | |||

| Peter ver-looks.after | the horses | ||||

| 'Peter tends the horses.' | |||||

| c. | Jan vlucht | uit zijn vaderland. | |||

| Jan flees | from his native country | ||||

| 'Jan flees from his homeland.' | |||||

| c'. | Jan ontvlucht | zijn vaderland. | |||

| Jan ont-flees | his native country | ||||

| 'Jan escapes his native country.' | |||||

Unfortunately, a systematic syntactic study of the alternations in (456) seems to be lacking so far, but there is one specific (and more complex) accusative/PP alternation that has been studied more intensively, the so-called locative alternation illustrated in (457), in which a locative PP alternates with a direct object. The discussion in Subsection II will therefore take this alternation as its starting point; information on accusative/PP alternations of the three types in (456) will be given as we go along.

| a. | Jan laadde | het hooi | op de wagen. | |

| Jan loaded | the hay | on the wagon |

| b. | Jan belaadde | de wagen | met hooi. | |

| Jan be-loaded | the wagon | with hay |

Some transitive verbs alternate with intransitive PO-verbs. Typical examples are schieten (op)to shoot (at), schrijven (aan)to write (at), and drinken (van)to drink (from) in (458); the accusative objects of the transitive verbs correspond to the nominal parts of the PP-complements.

| a. | Peter schiet | een vogel. | |

| Peter shoots | a bird |

| a'. | Peter schiet | op een vogel. | |

| Peter shoots | at a bird |

| b. | Marie schrijft | een artikel. | |||

| Marie writes | an article | ||||

| 'Marie is writing an article.' | |||||

| b'. | Marie schrijft | aan een artikel. | |||

| Marie writes | at an article | ||||

| 'Marie is writing at an article.' | |||||

| c. | Jan dronk | een glas wijn. | |

| Jan drank | a glass [of] wine |

| c'. | Jan dronk | van een glas wijn. | |

| Jan drank | from a glass [of] wine |

Alternations of the type in the (a)-examples in (458) exhibit a systematic difference in meaning: while the transitive verb in the primeless example takes an affected object, the complement of the intransitive PO-verb in the primed examples is not necessarily affected by the activity denoted by the verb. This is shown by the fact that (459a), but not (459b), is semantically incoherent. For this reason, the intransitive PO-verbs are sometimes called conative, as they describe “an attempted action without specifying whether the action was actually carried out” (Levin 1993:42).

| a. | $ | Jan schoot | een vogel, | maar | miste. |

| Jan shot | a bird | but | missed |

| b. | Jan schoot | op een vogel, | maar | miste. | |

| Jan shot | at a bird | but | missed |

The transitive verb in example (458b) takes a so-called incremental theme, i.e. a theme that is created step by step as a result of the activity denoted by the verb. Example (458b) is telic and thus implies that Marie’s activity, when completed, will have resulted in the writing of an article, as is clear from the fact that the use of the perfect tense in (460a) implies the existence of an article written by Marie. This implication is completely missing in the perfect-tense counterpart of example (458b') given in (460b). This difference may also explain why the direct but not the prepositional object can occur as a complement of an inherently telic predicate like voltooiento complete in the primed examples.

| a. | Marie heeft | gisteren | een artikel | geschreven. | |

| Marie has | yesterday | an article | written | ||

| 'Marie wrote an article yesterday.' | |||||

| a'. | Marie heeft | gisteren | een artikel | voltooid. | |

| Marie has | yesterday | an article | completed | ||

| 'Marie completed an article yesterday.' | |||||

| b. | Marie heeft | gisteren | aan een artikel | geschreven. | |

| Marie has | yesterday | at an article | written | ||

| 'Marie wrote at an article yesterday.' | |||||

| b'. | * | Marie heeft | gisteren | aan een artikel | voltooid. |

| Marie has | yesterday | at an article | completed |

The verb in example (458c) is similar to the verb in (458b) in that the theme changes over time, but now it does not come into existence but disappears step by step as a result of the activity denoted by the verb, which is why we can speak of a decremental theme; the perfect-tense counterpart of (458c) in (461a) implies that Jan’s glass is now empty. A similar implication is missing in the perfect-tense counterpart of example (458b') in (461b).

| a. | Jan heeft | daarnet | een glas wijn | gedronken. | |

| Jan has | just.now | a glass [of] wine | drank | ||

| 'Jan drank a glass of wine just now.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | daarnet | van een glas wijn | gedronken. | |

| Jan has | just.now | from a glass [of] wine | drank | ||

| 'Jan drank from a glass of wine just now.' | |||||

The number of simple verbs taking a decremental theme is quite small, since such verbs tend to take a verbal particle like op in (462); if we include such particle verbs, the number increases greatly. Note that the verbal particle cannot appear in the corresponding constructions with intransitive PO-verbs, which is probably due to the fact that verbal particles function as complementives and thus need a nominal phrase as their logical subject; cf. Section 2.2.1.

| a. | Jan snoepte | de kaas | *(op). | |

| Jan nibbled | the cheese | up | ||

| 'Jan nibbled the cheese up.' | ||||

| b. | Jan snoepte | van de kaas | (*op). | |

| Jan nibbled | the cheese | up | ||

| 'Jan nibbled/has been nibbling at the cheese.' | ||||

In cases such as (463), the accusative/PP alternation involves prefixation. De Haas & Trommelen (1993:67-8) describes the meaning of the derived verbs as “directing the action denoted by the input verb to a specific object” (our translation). Subsection II will return briefly to this kind of alternation.

| a. | Jan keek | naar het schilderij. | |||

| Jan looked | at the painting | ||||

| 'Jan looked at the painting.' | |||||

| a'. | Jan bekeek | het schilderij. | |||

| Jan looked.at | the painting | ||||

| 'Jan examined the painting.' | |||||

| b. | Petrarca | zong | over Laura. | |||

| Petrarch | sung | about Laura | ||||

| 'Petrarch sung about Laura.' | ||||||

| b'. | Petrarca bezong | Laura. | ||||

| Petrarch sung.about | Laura | |||||

| 'Petrarch sung (his praise) of Laura.' | ||||||

| c. | Jan reed | op het paard. | |

| Jan rode | on the horse |

| c'. | Jan bereed | het paard. | |

| Jan rode.on | the horse |

Example (464) provides a small sample of the verb types discussed in this section, taken mainly from Van Hout (1996:52-3).

| a. | Affected theme verbs: bijten (naar) ‘to bite (at)’, duwen (tegen) ‘push (against)’ schieten (op) ‘to shoot (at)’, schoppen (naar) ‘to kick (at)’, slaan (naar) ‘to hit (at)’, trappen (naar) ‘to kick (at)’, trekken (aan) ‘pull (on)’ |

| b. | Incremental theme verbs: bouwen (aan) ‘to build (on)’, breien (aan) ‘to knit (on)’, draaien (aan) ‘to turn’, naaien (aan) ‘to sew (on)’, schilderen (aan) ‘to paint (at)’, schrijven (aan) ‘to write (on)’ |

| c. | Decremental theme verbs: eten (van) ‘to eat (of)’, drinken (van) ‘to drink (from)’, nemen (van) ‘to take (of)’ |

| d. | be-verbs: denken aan/bedenken ‘to think of/to think up’, luisteren naar/beluisteren ‘to listen to/to listen carefully’, liegen tegen/beliegen ‘to lie to/to belie’, rijden op/berijden ‘to ride on’, spotten met/bespotten ‘to mock at/to mock’, spreken over/bespreken ‘to talk about/to discuss’, voelen aan/bevoelen ‘to feel at/to palpate’ |

The primed examples in (465) show that the accusative/PP alternation also occurs with ditransitive verbs.

| a. | Jan | vertelde | mij | het verhaal. | |

| Jan | told | me | the story |

| a'. | Jan vertelde | mij | over de overstroming. | |

| Jan told | me | about the flood |

| b. | Jan vroeg | me een beloning. | |

| Jan asked | me a reward |

| b'. | Jan vroeg | mij | om een beloning. | |

| Jan asked | me | for a reward |

However, the examples in (466) show that this alternation is not possible when the dative argument appears as a PP, although it should be noted that periphrastic indirect objects are acceptable when the object is clausal; cf. Jan vroeg aan mij om hem een beloning te gevenJan asked me to give him a reward.

| a. | Jan | vertelde | het verhaal | aan mij. | |

| Jan | told | the story | to me |

| a'. | *? | Jan vertelde | <aan mij> | over de overstroming <aan mij>. |

| Jan told | to me | about the flood |

| b. | Jan vroeg | een beloning aan me. | |

| Jan asked | me a reward |

| b'. | ?? | Jan vroeg | <aan mij> | om een beloning <aan mij>. |

| Jan asked | to me | for a reward |

We refer the reader to the introduction to Section 2.3 for a further discussion of the differences between the primed examples in (465) and (466).

A well-known verb-frame alternation in English is the so-called locative alternation shown in (467). The two alternants both contain a located and a reference (= location-denoting) object, but the way they are syntactically realized is different. Example (467a) is a resultative construction in which the reference object is expressed by the complementive PP on his face that is predicated of the located object mud, which in turn is syntactically realized as the accusative object of the clause. In example (467b), on the other hand, the reference object is realized as the accusative object, while the located object is realized by a with-PP; cf. Levin (1993) for further English data.

| a. | John smeared mud on his face. |

| b. | John smeared his face with mud. |

The examples in (468) show that Dutch has a similar verb-frame alternation. However, the Dutch alternation differs from its English counterpart in that it is accompanied by a morphological change; the verb in (468b) seems to be derived from the verb in (468a) by the prefix be-; cf. Hoekstra et al. (1987).

| a. | Jan smeerde | modder | op zijn gezicht. | |

| Jan smeared | mud | on his face |

| b. | Jan be-smeerde | zijn gezicht | met modder. | |

| Jan be-smeared | his face | with mud |

The prefix be- is part of a small set of prefixes with a number of remarkable properties. Subsection A begins the discussion of these affixes in derived verbs denoting a change of location or a path. Subsection B shows that constructions containing such verbs are quite similar to resultative constructions, i.e. constructions with a complementive.

The prefix be- in example (468b) belongs to a small set of prefixes that are special in that they have the ability to change the category of the stem. Normally, this property is restricted to suffixes, as expressed by Williams’ (1981b) righthand head rule, according to which the rightmost member in a morphologically complex word determines the category (as well as other properties) of the complex word. This is what we find in Table (469), where the suffixes -el, -er, and -ig determine the category of the derived form; they are verb-creating suffixes.

| suffix | stem | complex verb |

| -el | brokN ‘piece’ | brokkelen ‘to crumble’ |

| hinkV ‘to limp’ | hinkelen ‘to play hopscotch’ | |

| -er | snotN ‘snot’ | snotteren ‘to snivel’ |

| kiepV ‘to dump’ | kieperen ‘to dump/tumble’ | |

| -ig | steenN ‘stone’ | stenigen ‘to stone’ |

| reinA ‘clean’ | reinigen ‘to clean’ |

Table (470) shows that the prefixes be-, ver- and ont- can also turn nouns and adjectives into verbs. The only other Dutch prefix with a similar category-changing ability is the nominalizing prefix ge-, which was discussed in Section N14.3.1.4; cf. zeurenV to nag - gezeurN nagging.

| suffix | stem | complex verb |

| be- | dijkN ‘dike’ | bedijken ‘to dike in’ |

| zatA ‘drunk’ | bezatten ‘to get/make drunk’ | |

| smerenV ‘smear’ | besmeren ‘to smear on’ | |

| ver- | zoolN ‘sole’ | verzolen ‘to sole’ |

| dunA ‘thin’ | verdunnen ‘to dilute’ | |

| zwijgenV ‘to be silent’ | verzwijgen ‘to keep silent about’ | |

| ont- | bosN ‘forest’ | ontbossen ‘to deforest’ |

| nuchterA ‘sober’ | ontnuchteren ‘to sober up’ | |

| bindenV ‘to bind’ | ontbinden ‘to dissolve’ |

Table (470) represents only a few typical examples, without doing justice to the fact that the nine types of derived verbs can be further divided into several subclasses with special semantic properties; cf. Booij (2015d), and especially De Haas & Trommelen (1993) for an extensive discussion. Since this section is concerned with the locative alternation, we will focus especially on those derived verbs that denote a change of location or a path; cf. Section P32.3.1.1 for these terms.

Deverbal verbs prefixed with be- come in different kinds. For example, Subsection I has shown that in many cases the accusative object of the derived verb corresponds to the nominal part of a prepositional phrase in constructions with the corresponding simple verb; cf. (471).

| a. | Jan spreekt | over het probleem. | |

| Jan talks | about the problem |

| a'. | Jan bespreekt | het probleem. | |

| Jan discusses | the problem |

| b. | De dokter | voelde | aan zijn arm. | |

| the doctor | felt | at his arm |

| b'. | De dokter | bevoelde zijn arm. | |

| the doctor | examined his arm |

The present discussion focuses on the locative alternation in (472), in which the prepositional reference object of (472a) appears as the direct object of the derived verb in (472b). That the noun phrase has the grammatical function of direct object in this example will be clear from its promotion to subject in the corresponding passive construction in (472b'). The accusative located object of (472a) appears as an optional met-PP in the (b)-examples in (472); when it is omitted, the located object is semantically implied in the sense that we can still infer that the reference object is covered with “pastable” objects.

| a. | Jan plakt | posters | op de muur. | |

| Jan pastes | posters | on the wall |

| b. | Jan be-plakt | de muur | (met posters). | active | |

| Jan be-pastes | the wall | with posters |

| b'. | De muur | wordt | be-plakt | (met posters). | passive | |

| the wall | is | be-pasted | with posters |

There is a clear difference in meaning between the two examples in (472a&b): while (472a) is compatible with a reading in which the located object covers only part of the reference object, (472b) implies that the reference object is completely (or at least largely) covered by the located object. This comes to the fore by replacing the plural noun phrase de posters in (472) by a singular one; while (473a) is easily possible, example (473b) is only acceptable in the less common case that the poster completely covers the wall.

| a. | Jan plakt | een poster | op de muur. | |

| Jan pastes | a poster | on the wall | ||

| 'Jan is pasting a poster on the wall.' | ||||

| b. | $ | Jan be-plakt | de muur | met een poster. |

| Jan be-pastes | the wall | with a poster |

This contrast suggests that deverbal be-verbs express that their objects are affected as a whole. This could be further supported by the fact that example (472a) also alternates with the construction in (474a), where the notion of total affectedness is expressed by the adjective volfull. The crucial observation is that this adjective is incompatible with deverbal be-verbs; this could be explained by claiming that (474b) is tautological: vol and the prefix be- perform in a sense the same semantic function. We will return to a more formal account of this point in Subsection B.

| a. | Jan plakt | de muur | vol (met posters). | |

| Jan pastes | the wall | full with posters |

| b. | * | Jan be-plakt | de muur | vol | (met posters). |

| Jan be-pastes | the wall | full | with posters |

Note in passing that the notion of total affectedness should not be taken too literally, since the extent to which the reference object is affected can be further specified by attributive modifiers such as heel/halfwhole/half or degree modifiers such as helemaal/gedeeltelijkcompletely/partly; cf. (475). This suggests that the relevant aspect of meaning is simply “affectedness”, with the interpretation of “total affectedness” as a default value that can be overridden by the addition of the modifiers mentioned above.

| a. | Jan be-plakt | de hele/halve muur | (met posters). | |

| Jan be-pastes | the whole/half wall | with posters |

| a'. | Jan be-plakt | de muur | helemaal/gedeeltelijk | (met posters). | |

| Jan be-pastes | the wall | completely/partly | with posters |

| b. | Jan plakt | de hele/halve muur | vol | (met posters). | |

| Jan pastes | the whole/half wall | full | with posters |

| b'. | Jan plakt | de muur | helemaal/gedeeltelijk | vol | (met posters). | |

| Jan pastes | the wall | completely/partly | full | with posters |

Table 3 lists a small sample of verbs of the type in (472). Note that not all verbs in this table can be combined with volfull; this is possible with the first five, but not with the last three. This suggests that the prefix be- and the adjective vol are not fully equivalent semantically; cf. Van Hout (1996:48) for a first attempt to describe this difference in meaning.

| stem | verb | translation |

| hangen ‘to hang’ | behangen met | to paper with |

| laden ‘to load’ | beladen met | to load with |

| leggen ‘to put’ | beleggen met | to fill (a sandwich) with |

| plakken ‘to paste’ | beplakken met | to paste with |

| smeren ‘to smear’ | besmeren met | to smear with |

| sproeien ‘to spray’ | besproeien met | to spray with |

| spuiten ‘to spray’ | bespuiten met | to spray with |

| strooien ‘to strew’ | bestrooien met | to strew with |

The verbs in Table 3 do not form a uniform set, and may exhibit diverging behavior in other respects. For example, while the verb plakken must be prefixed with be- in order for the reference object to appear as an accusative object, this is not the case for the verbs ladento load, (een boterham) smerento butter (a sandwich), (het gazon) sproeiento water (the lawn) and (de auto) spuitento spray (the car); the examples in (476) show for two of these verbs that they alternate not only with the (b) but also with the (c)-examples.

| a. | Jan smeert boter | op zijn brood. | |

| Jan smears butter | on his bread |

| a'. | Jan laadt het hooi | op de wagen. | |

| Jan loads the hay | on the truck |

| b. | Jan be-smeert zijn brood | (met boter). | |

| Jan be-smears his bread | with butter |

| b'. | Jan be-laadt de wagen (met hooi). | |

| Jan be-loads the wagon with hay |

| c. | Jan smeert | zijn brood | (??met boter). | |

| Jan smears his bread | with butter |

| c'. | Jan laadt | de wagen (?met hooi). | |

| Jan loads | the wagon with hay |

Our judgments in (476) suggest that the met-PP produces a slightly better result in the (b) than in the (c)-examples, but this has not yet been seriously investigated. It is also interesting to note that Dutch deverbal be-verbs differ crucially from their English counterparts in that they always allow the omission of the met-PP. Hoekstra et al. (1987) note that English deverbal be-verbs fall into two subgroups here: verbs corresponding to Dutch verbs that allow the (c)-alternant in (476), like to load and to spray in the (a)-examples in (477), tend to take an optional with-PP; verbs corresponding to Dutch verbs that do not allow this alternant, like to hang and to pack in the (b)-examples, take an obligatory with-PP (cf. Hoekstra & Mulder, 1990:20, for further discussion).

| a. | John was loading the hay (on the wagon). |

| a'. | Jan was spraying his car (with paint). |

| b. | John was hanging the wall *(with posters). |

| b'. | John was packing the donkey *(with trunks). |

De Haas & Trommelen (1993:68-9) shows that denominal verbs prefixed with be- can be of different types; here we are interested in cases such as (478b). Example (478b) has a similar meaning to (478a), but additionally expresses that the reference object is totally affected; after the completion of the activity, the bread will be completely covered with butter, on one side. Example (478b) also shows that the located object boterbutter has in a sense been incorporated into the verb, i.e. has become an inherent part of the be-verb. The prepositional reference object op het broodon the bread, on the other hand, appears as the accusative object of the denominal verb: it is promoted to subject of the clause in the regular passive construction in (478b').

| a. | Jan smeert | boter | op het brood. | |

| Jan smears | butter | on the bread |

| b. | Jan be-botert | het brood. | active | |

| Jan be-butters | the bread |

| b'. | Het brood | wordt | (door Jan) | beboterd. | passive | |

| the bread | is | by Jan | buttered |

The examples in (479a&b) show that there is a striking syntactic difference between the two examples in (478a&b); while the assertion in (478b) can be made more specific by adding a substance-denoting met-PP, the addition of such a PP leads to an incoherent reading of (478a). To express the more specific assertion, we need to replace the direct object boter with margarine, as in (479a'). This shows that the denotation of the nominal part of the be-verb has become less prominent as a result of incorporation.

| a. | * | Jan smeert | boter | op het brood | met margarine. |

| Jan smears | butter | on the bread | with margarine |

| a'. | Jan smeert | margarine | op het brood. | |

| Jan smears | margarine | on the bread |

| b. | Jan be-botert | het brood | met margarine. | |

| Jan be-butters | the bread | with margarine |

The examples in (480) further show that the formation of be-verbs is not fully productive; a noun like jam in (480) cannot be used as the stem of a be-verb. This suggests that the attested denominal be-verbs are listed in the lexicon.

| a. | Jan smeert | jam | op | zijn brood. | |

| Jan smears | jam | on | his bread |

| b. | * | Jan be-jamt zijn brood. |

A small sample of be-verbs of the type in (478) is given in Table 4. The first column gives the nominal stem of the verb and its English translation, the second column the derived verb, and the third column a translation or paraphrase in English.

| stem | verb | translation |

| bos ‘wood’ | bebossen | to afforest |

| dijk ‘dike’ | bedijken | to put dikes around/next to |

| mest ‘manure’ | bemesten | to manure/fertilize |

| modder ‘mud’ | bemodderen | to put mud on |

| schaduw ‘shadow’ | beschaduwen | to shade |

| vracht ‘load’ | bevrachten | to load |

| water ‘water’ | bewateren | to water |

Note that it is sometimes difficult to tell whether we are dealing with a denominal or a deverbal be-verb. For instance, the examples in (481) suggest that beplantento plant with can be deverbal or denominal.

| a. | Jan plantV | rozen | in zijn tuin. | |

| Jan plants | roses | in his garden |

| b. | Jan zet | plantenN | in zijn tuin. | |

| Jan puts | plants | in his garden |

| c. | Jan be-plant | zijn tuin | (met rozen). | |

| Jan be-plants | his garden | with roses |

The examples discussed in the previous subsections involve a certain change of location; some entity is relocated with respect to some reference object. The examples in (482) are different in that they involve a path: the (a)-examples express that Jan travels a path that has its endpoint inside the hall, and the (b)-examples that Peter travels a path that goes to the top of the mountain.

| a. | Jan treedt | de zaal | binnen. | |||

| Jan steps | the hall | inside | ||||

| 'Jan steps into the hall.' | ||||||

| a'. | Jan be-treedt | de zaal. | ||||

| Jan be-steps | the hall | |||||

| 'Jan enters the hall.' | ||||||

| b. | Peter klimt | de berg | op. | |||

| Peter climbs | the mountain | up | ||||

| 'Peter climbs the mountain.' | ||||||

| b'. | Peter be-klimt | de berg. | ||||

| Peter be-climbs | the mountain | |||||

| 'Peter climbs up the mountain.' | ||||||

Levin (1993:43) discusses this alternation as a special case, but it seems that we are basically dealing with the same phenomenon; the verb is prefixed with be-, and the postpositional phrases de zaal binnen and de berg op are replaced by noun phrases that function as direct objects. The fact that the noun phrases in the primeless and primed examples have different syntactic functions is clear from the fact that they behave differently under passivization; the complement of the postpositional phrase in the primeless examples cannot be promoted to subject, whereas the complement of the be-verb in the primed examples can; this is illustrated in (483) for the (b)-examples in (482).

| a. | * | De berg | werd | vaak | op | geklommen. |

| the mountain | was | often | onto | climbed |

| b. | De berg | werd | vaak | beklommen. | |

| the mountain | was | often | be-climbed |

However, there is also an essential difference between the change-of-location cases and the directional cases; the stem of the directional be-verbs typically belongs to the class of unaccusative verbs. The examples in (484) illustrate the inability of verbs of transitive resultative constructions (i.e. constructions in which the complementive is predicated of an accusative noun phrase) to act as the stem of a directional be-verb.

| a. | Jan duwt | de auto | de berg | op. | |

| Jan pushes | the car | the mountain | onto | ||

| 'Jan pushes the car onto the mountain.' | |||||

| a'. | * | Jan be-duwt de berg (met de auto’s). |

| b. | De politie | slaat | de demonstranten | het ziekenhuis | in. | |

| the police | hits | the demonstrators | the hospital | into | ||

| 'The police are hitting the demonstrators into the hospital.' | ||||||

| b'. | * | De politie be-slaat het ziekenhuis (met demonstranten). |

be-verbs denoting a change of location are not restricted in this way, as can be seen from the difference between the (b)-examples in (484) and the examples in (485).

| a. | Jan slaat | de platen | op de muur. | |

| Jan hits | the slabs | onto the wall |

| b. | Jan be-slaat de muur met platen. |

In fact, the stems of deverbal be-verbs denoting a change of location are typically transitive. Unaccusative verbs of change-of-location verbs such as vallento fall cannot be used as input to such be-verbs; the examples in (486b&c) show that the reference object cannot occur as an accusative or nominative noun phrase, and that the located object cannot be realized as a met-PP.

| a. | De kralen | vielen | op de grond. | |

| the beads | fell | to the ground |

| b. | * | De kralen | be-vielen | de grond. |

| the beads | be-fell | the ground |

| c. | * | De grond | be-viel | met kralen. |

| the ground | be-fell | with beads |

The only possible counterexample we could find is given in (487), but it seems likely that we are dealing here with a directional rather than a change-of-location construction, since (487c) does not necessarily imply that the lion will land on top of the gazelle; the examples in (487a&b) show that this also holds for the directional construction, but not for the change-of-location construction.

| a. | De leeuw | sprong | op de gazelle | ($maar | hij | miste). | change of location | |

| the lion | jumped | onto the gazelle | but | he | missed |

| b. | De leeuw | sprong | naar de gazelle | toe | (maar | hij | miste). | directional | |

| the lion | jumped | to the gazelle | toe | but | he | missed |

| c. | De leeuw | be-sprong | de gazelle | (maar | hij | miste). | |

| the lion | be-jumped | the gazelle | but | he | missed |

Some possible cases of unaccusative verbs that can be used as input for the formation of directional be-verbs denoting a path are given in Table 5; these cases require more in-depth investigation.

| stem | verb | translation |

| naderen ‘approach’ | benaderen | to approach (something) |

| reizen ‘to travel’ | bereizen | to travel (across/through) |

| springen ‘to jump’ | bespringen | to pounce |

| sluipen ‘to steal/prowl’ | besluipen | to stalk |

| stijgen ‘to rise’ | bestijgen | to mount/ascend |

| varen ‘to sail’ | bevaren | to sail (the sea) |

Denominal ont-verbs like ontharento depilate and ontkurkento uncork in the singly-primed examples in (488) express in a sense the opposite of the denominal be-verbs discussed in Subsection 2; both types denote a change of location, but whereas in the case of the denominal be-verbs the reference object refers to the new position of the moved entity, in the case of the denominal ont-verbs it refers to its original position. The doubly-primed examples show that, as with the be-verbs, the reference object appears as the direct object of the ont-verbs, as can be seen from the fact that it is promoted to the subject in the regular passive.

| a. | Jan haalt | de haren | van zijn benen. | |

| Jan removes | the hairs | from his legs |

| a'. | Jan ont-haart | zijn benen. | active | |

| Jan ont-hair-s | his legs | |||

| 'Jan depilates his legs.' | ||||

| a''. | Zijn benen | worden | ont-haard. | passive | |

| his legs | are | ont-hair-ed |

| b. | Marie haalt | de kurk | uit | de fles. | |

| Marie removes | the cork | out.of | the bottle |

| b'. | Marie ont-kurkt | de fles. | active | |

| Marie ont-cork-s | the bottle | |||

| 'Marie uncorks the bottle.' | ||||

| b''. | De fles | wordt | ont-kurkt. | passive | |

| the bottle | is | ont-cork-ed |

Table 6 provides some more examples of denominal verbs prefixed with ont-. Sometimes denominal be- and ont-verbs are antonymous, as in bebossen and ontbossen, but in many other cases there is no antonym. This strongly suggests that the formation of be- and ont-verbs is not a productive process, and that the attested cases are listed in the lexicon.

| stem | verb | translation |

| bos ‘forest’ | ontbossen | to deforest |

| grond ‘soil/basis’ | ontgronden | to take away the soil/basis |

| hoofd ‘head’ | onthoofden | to decapitate |

| kalk ‘lime’ | ontkalken | to decalcify |

| volk ‘people’ | ontvolken | to depopulate |

The examples in (489) denote a metaphorical path from one state of affairs to another. The referent of the noun phrase Krakras (a character from a Dutch series of children’s books) changes from a state in which it has the form of an unpalatable-looking bird to a state in which it looks like a tasty duck that can be used as an ingredient for soup.

| a. | De heks | verandert | Krakras | in een smakelijke soepeend. | |

| the witch | changes | Krakras | into a tasty soup.duck |

| b. | Krakras | verandert | in een smakelijke soepeend. | |

| Krakras | changes | into a tasty soup-duck |

Constructions such as (489) often alternate with constructions using denominal ver-verbs; an example is given in the (a)-examples of (490). The (b)-examples show that a ver-verb corresponding to the causative counterparts of veranderen sounds a bit awkward.

| a. | Het water | veranderde | in damp. | |

| the water | changed | into vapor |

| a'. | Het water | verdampte. | |

| the water | evaporated |

| b. | De hitte | veranderde | het water | in damp. | |

| the heat | changed | the water | into vapor |

| b'. | ? | De hitte | verdampte | het water. |

| the heat | evaporated | the water |

Similar cases are listed in Table 7. Sometimes the meaning of the denominal ver-verb has narrowed down to the paraphrase given after the arrow “⇒”.

| verb | translation | |

| film ‘movie’ | verfilmen | change into a movie ⇒ adapt (a story) for the screen |

| gas ‘gas’ | vergassen | change into gas |

| gras ‘grass’ | vergrassen | change into grassland |

| kool ‘coal’ | verkolen | carbonize |

| snoep ‘sweets’ | versnoepen | change into sweets ⇒ spend money on sweets |

| water ‘water’ | verwateren | change into water ⇒ dilute |

Note in passing that the deadjectival verbs prefixed by ver- in the primed examples in (491) express a semantic aspect similar to those in Table 7, but are related to the inchoative copular or resultative constructions in the primeless examples.

| a. | De lakens | worden | geel. | |

| the sheets | become | yellow |

| a'. | De lakens | vergelen. | |

| the sheets | get.yellow |

| b. | Deze zeep | maakt | de was | zachter. | |

| this soap | makes | the laundry | softer |

| b'. | Deze zeep | verzacht | de was. | |

| this soap | softens | the laundry |

The prefixes be-, ver-, and ont- have the ability to change the category of the stem, in this way violating the righthand head rule. This casts some doubt on the idea that we are dealing with ordinary prefixes, and it has in fact been suggested that these elements have a syntactic rather than a morphological function; they are complementives that have become part of the complex verb through incorporation. The following subsections present the gist of this proposal and discuss a number of empirical facts that support it.

The examples in (492a&b) show again that be-verbs can sometimes be paraphrased by a resultative construction with the adjectival complementive vol; cf. Subsection A1. Example (492c) further shows that be- and vol are in complementary distribution.

| a. | Ik | be-plant | de tuin | (met rozen). | |

| I | be-plant | the garden | with roses |

| b. | Ik | plant de tuin | vol | (met rozen). | |

| I | plant the garden | full | with roses |

| c. | * | Ik | be-plant | de tuin | vol | (met rozen). |

| I | be-plant | the garden | full | with roses |

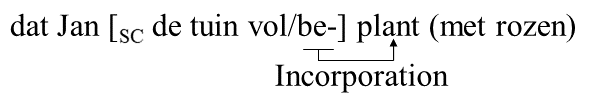

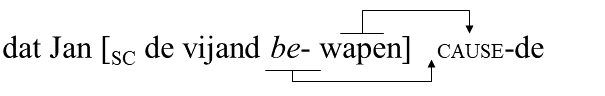

Following an earlier proposal in Dik (1980:36), Hoekstra et al. (1987) have argued that the pattern in (492) shows that be- functions syntactically as a complementive comparable to vol. However, it has the special property that it incorporates into the verb; if we assume that the complementive and the noun phrase of which it is predicated form a small clause, the analysis of the examples in (492a&b) looks as shown in (493); while vol remains inside the small clause, be- is moved out to incorporate into the verb plant.

|

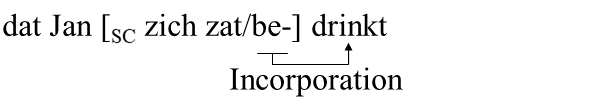

Example (494) shows that this analysis can be applied more generally. The fact that the simplex reflexive zich can be used with the complex verb bedrinkenget drunk in (494a) can be seen as an empirical argument for the claim that the element be- functions as a complementive; example (494b) shows that, unlike internal theme arguments of verbs, logical subjects of complementives can normally be realized by such a reflexive (cf. Sections 2.5.2, sub I, and N22.4 for discussion).

| a. | dat hij | zich | be-drinkt. | |

| that he | refl | be-drinks | ||

| 'that he is getting very drunk.' | ||||

| b. | dat hij | zich | zat | drinkt. | |

| that he | refl | very.drunk | drinks | ||

| 'that he is getting very drunk.' | |||||

| c. |  |

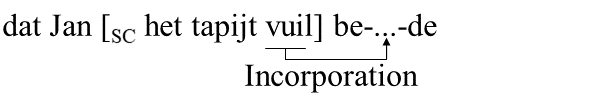

The following subsections will show that a considerable subset of complex verbs prefixed by be-, ver-, and ont- can be derived in a similar way, i.e. by incorporation into the verb. The extent to which this type of analysis can be applied to the class as a whole is not a priori clear. For instance, the semantic correspondence between the examples in (495a&b) might lead to the idea that they have a similar underlying structure, in which the adjective vuildirty acts as a complementive, and that be- is thus not the head of a small cause, but a causative element that attracts the predicative head of the small clause, as in (495c).

| a. | dat | Jan [SC | het tapijt | vuil] | maakte. | |

| that | Jan | the carpet | dirty | made |

| b. | dat | Jan | het tapijt | be-vuil-de. | |

| that | Jan | the carpet | be-dirty-past |

| c. |  |

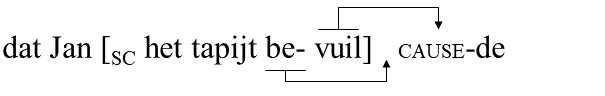

However, this alternative analysis may be less attractive, since it reintroduces the problem that the prefix be- is exceptional in that it determines the category of the complex form in violation of the righthand head rule. It is therefore not surprising that it has been suggested that (495c) is in fact not the correct analysis. Hoekstra (2004:365ff) argues that the derivation of (495b) proceeds in essentially the same way as in (493), with the difference that the verb into which be- is incorporated is an abstract (phonetically empty) causative verb: the adjective must also be incorporated in order to satisfy the requirement that the prefix be- be morphologically supported. See Mulder (1992: §9) for an alternative proposal.

|

Note, however, that this analysis implies that be- is polysemous: in examples like (492c) and (494b) it is a monadic predicate expressing some notion of total affectedness, whereas in (496) it functions as a dyadic predicate with a meaning comparable to the copular verb zijnto be. In fact, Hoekstra suggests that this does not exhaust the possibilities, and proposes a derivation for “ornative” be- verbs such as bewapenento arm along the lines of (497b), in which be- is again a dyadic predicate, but now with a meaning comparable to the verb hebbento have.

| a. | dat | Jan de vijand | be-wapen-de. | |

| that | Jan the enemy | be-arm-past | ||

| 'that Jan was arming the enemy.' | ||||

| b. |  |

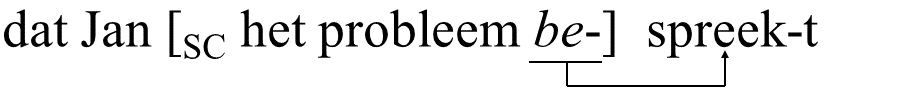

Of course, derivations similar to those in (496) and (497) can also be used to derive denominal and deadjectival ver- and ont-verbs. Another case discussed in Hoekstra (2004) is the construction in (498). He claims that this is actually an applicative (= preposition incorporation) construction of the type described in Baker (1988) for languages like Chichewa; cf. also Voskuyl (1996). Hoekstra’s analysis is given in (498b).

| a. | dat | Jan het probleem | be-spreek-t | . | |

| that | Jan the problem | be-speak-present | |||

| 'that Jan discusses the problem.' | |||||

| b. |  |

As the discussion above shows, it seems possible to explain a large variety of be-, ver-, and ont-verbs by syntactic incorporation. This proposal is motivated not only by the fact that it can account for the exceptional behavior of these prefixes with respect to the righthand head rule, but also by a larger set of empirical data that will be discussed in the following subsections.

The incorporation analysis can immediately account for the complementarity in the distribution of be- and the adjectival complementive volfull in example (492c), by appealing to the more general restriction that a clause can contain at most one complementive. Further examples showing that verbs prefixed by be-, ver-, and ont- cannot be combined with a complementive are given in (499); cf. Section 2.2.1, sub IV, for discussion.

| a. | dat | de dokter | hem | genezen | acht/*behandelt. | |

| that | the doctor | him | cured | considers/treats | ||

| 'that the doctor considers him cured.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan | het huis | groter | maakt/*verbouwt. | |

| that | Jan | the house | bigger | makes/rebuilds | ||

| 'that Jan is making the house bigger.' | ||||||

| c. | dat | Marie | haar benen | glad | scheert/*onthaart. | |

| that | Marie | her legs | smooth | shaves/depilates | ||

| 'that Marie is shaving her legs smooth.' | ||||||

At first glance, the examples in (500) seem to provide counterexamples to the claim that complex verbs prefixed by be- cannot take a complementive; the tot/als-phrases seem to be predicated of the accusative noun phrases and thus function as complementives. However, there are at least two reasons to reject this conclusion: (i) the tot/als-phrases are optional; (i) they can occur in postverbal position. These facts would follow immediately if it is the prefix that functions as a complementive: the tot-phrases would then have a different function, and therefore would not be expected to exhibit the behavior of standard complementives.

| a. | dat | Jan hem | <tot voorzitter> | benoemt <tot voorzitter>. | |

| that | Jan him | to chairman | appoints | ||

| 'that Jan appoints him chairman.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Jan haar | <tot ontrouw> | verleidt <tot ontrouw>. | |

| that | Jan her | to unfaithfulness | seduces | ||

| 'that Jan is seducing her to becoming unfaithful.' | |||||

| c. | dat | de rechter | hem | <tot de galg> | veroordeelt <tot de galg>. | |

| that | the judge | him | to the gallows | condemns | ||

| 'that the judge condemns him to the gallows.' | ||||||

| d. | dat | Jan | hem | <tot de voordeur> | begeleidt <tot de voordeur>. | |

| that | Jan | him | to the front.door | accompanies | ||

| 'that Jan is accompanying him to the front door.' | ||||||

| e. | dat | ik | hem | <als mijn vriend> | beschouw <als mijn vriend>. | |

| that | I | him | as my friend | consider | ||

| 'that I consider him as my friend.' | ||||||

This proposal is very close to the one proposed for the constructions with and without the verbal particle neerdown in (501); Section 2.2.1, sub IV, has shown that the contrast between the (a) and the (b)-examples is due to the fact that the particle neerdown must be analyzed as a complementive; this means that the PP op de tafel cannot be analyzed as a complementive in the (b)-examples; it is therefore to be expected that the (b)-examples differ from the (a)-examples in that they allow the PP to be omitted or to occur in postverbal position.

| a. | Jan heeft | het boek | *(op de tafel) | gelegd. | |

| Jan has | the book | on the table | put |

| a'. | * | Jan heeft | het boek | gelegd | op de tafel. |

| Jan has | the book | put | on the table |

| b. | Jan heeft | het boek | (op de tafel) | neer | gelegd. | |

| Jan has | the book | on the table | down | put |

| b'. | Jan heeft | het boek | neer | gelegd | op de tafel. | |

| Jan has | the book | down | put | on the table |

If the prefixes be-, ver-, and ont- do indeed originate as predicative heads of small clauses, we would expect them to have an effect on argument structure similar to that of complementives and verbal particles; cf. Section 2.2. The examples in (502a&b) show that the use of an adjectival complementive can add an argument to the otherwise impersonal verb vriezento freeze, and (502c) shows that prefixation with be- can have a similar effect. The fact that (502b&c) both take the perfect auxiliary zijnto be shows that we are dealing with unaccusative structures, and this is of course to be expected, since the additional argument is introduced as the subject of the small-clause heads dood and be-.

| a. | Het/*Jan | heeft | gevroren. | |

| it/Jan | has | frozen |

| b. | Jan is | dood | gevroren. | |

| Jan is | to.death | frozen |

| c. | Jan is bevroren. | |

| Jan is frozen |

Prefixation with ver- and ont- can also add an argument to the otherwise impersonal verbs waaiento blow and dooiento thaw, as shown in (503)

| a. | Het/*Haar kapsel | waait. | |

| it/her coiffure | blows |

| a'. | Haar kapsel | verwaait. | |

| her coiffure | is.blown.in.disorder |

| b. | Het/*De spinazie | dooit. | |

| it/the spinach | thaws |

| b'. | De spinazie | ontdooit. | |

| the spinach | defrosts |

The primeless examples in (504) show that the use of the adjectival complementive platflat adds an argument to the otherwise intransitive verb lopento walk and that prefixation with be- again has a similar effect. The primed examples show the same for the prefix ver-.

| a. | Jan loopt | (*het gras). | |

| Jan walks | the grass |

| a'. | Jan vloekt | (*zijn computer). | |

| Jan swears | his computer |

| b. | Jan loopt | het gras | plat. | |

| Jan walks | the grass | flat |

| b'. | Jan vloekt | zijn computer | uit. | |

| Jan swears | his computer | prt. |

| c. | Jan beloopt | het gras. | |

| Jan walks.on | the grass |

| c'. | Jan vervloekt | zijn computer | |

| Jan scolds | his computer |

Nice minimal pairs are less easy to find for verbs prefixed with ont-, but possible cases are Jan loopt zijn straf misJan misses his punishment and Jan ontloopt zijn strafJan escapes his punishment can be used to illustrate the main point.

The (a)-examples in (505) show that adding a locational complementive to an intransitive verb can also produce an unaccusative verb; whereas (505a) takes the auxiliary hebbento have, (505b) with the complementive wegaway takes the auxiliary zijnto be, which is sufficient to assume unaccusative status. The (b)-examples show that prefixing with ver- can have a similar effect; other unaccusative verbs prefixed with ver- are vertrekkento leave and vertoevento stay but these do not have an intransitive counterpart in the modern language . We have not found any cases with the prefixes be- and ont- that have this effect.

| a. | Jan heeft/*is | gewandeld. | |

| Jan has/is | walked |

| a'. | Jan is/*heeft | weg | gewandeld. | |

| Jan is/has | away | walked |

| b. | Jan heeft/*is | gedwaald. | |

| Jan has/is | roamed |

| b'. | Jan is/*heeft | verdwaald. | |

| Jan is/has | lost.his.way |

Example (506a) further shows that the addition of a complementive to an unaccusative verb normally has no effect on the number of arguments. However, the nominative argument is now no longer licensed by the verb but by the complementive, as can be seen from the fact that the complementive cannot be omitted. Example (506b) shows that the nominative argument can also be licensed by the prefix ver-, which supports the underlying small-clause analysis. The primed examples show that the same holds for transitive verbs; the number of arguments is not affected, but the direct object is semantically licensed not by the verb but by the adjectival complementive or verbal prefix.

| a. | Het huis | viel | *(in elkaar). | |

| the house | fell | apart |

| a'. | Jan dronk | zijn verdriet | *(weg). | |

| Jan drank | his sorrow | away |

| b. | Het huis | verviel. | |

| the house | decayed |

| b'. | Jan | verdronk | zijn verdriet. | |

| Jan | drank.away | his sorrow |

As with verbal particles, prefixation can affect the aspectual properties of the construction; cf. Van Hout (1996:176ff). We show this here with the unaccusative verb brandento burn; whereas the construction in (507a) is atelic, the constructions in (507b&c) with a particle verb and a verb prefixed by ver- are telic. This aspectual difference is clear from the fact that the former takes the perfect auxiliary hebbento have and the latter the perfect auxiliary zijnto be; cf. Section 2.1.2, sub III, for further discussion of the relation between auxiliary selection and telicity.

| a. | Het huis | heeft/*is | gebrand. | |

| the house | has/is | burnt |

| b. | Het huis | is/*heeft | afgebrand. | |

| the house | is/has | down-burnt |

| c. | Het huis | is/*heeft | verbrand. | |

| the house | is/has | burnt.down |

The subsections above discussed the hypothesis proposed in Hoekstra et al. (1987) that the prefixes be-, ver-, and ont- function syntactically as complementives, and provided empirical evidence in support of this claim. We should be cautious, however, because the derivation of deverbal verbs prefixed by these prefixes is not a fully productive process, raising complex questions about the relationship between syntax and morphology. Furthermore, many of the putative input verbs are obsolete or no longer used with the intended meaning, and the output forms often exhibit idiosyncratic behavior. Given the complexity of the issue, this hypothesis needs to be investigated more thoroughly.