- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Three different types of degree modifiers can be distinguished: amplifiers, such as zeervery, which scale upward from a tacitly assumed standard value or norm, downtoners, such as vrijrather, which scale downward from a tacitly assumed standard value or norm, and neutral degree modifiers, such as min of meermore or less, which are neutral in this regard.

| a. | Amplifiers scale upward from a tacitly assumed standard value/norm. |

| b. | Downtoners scale downward from a tacitly assumed standard value/norm. |

| c. | Neutral modifiers are neutral with respect to the tacitly assumed standard value/norm. |

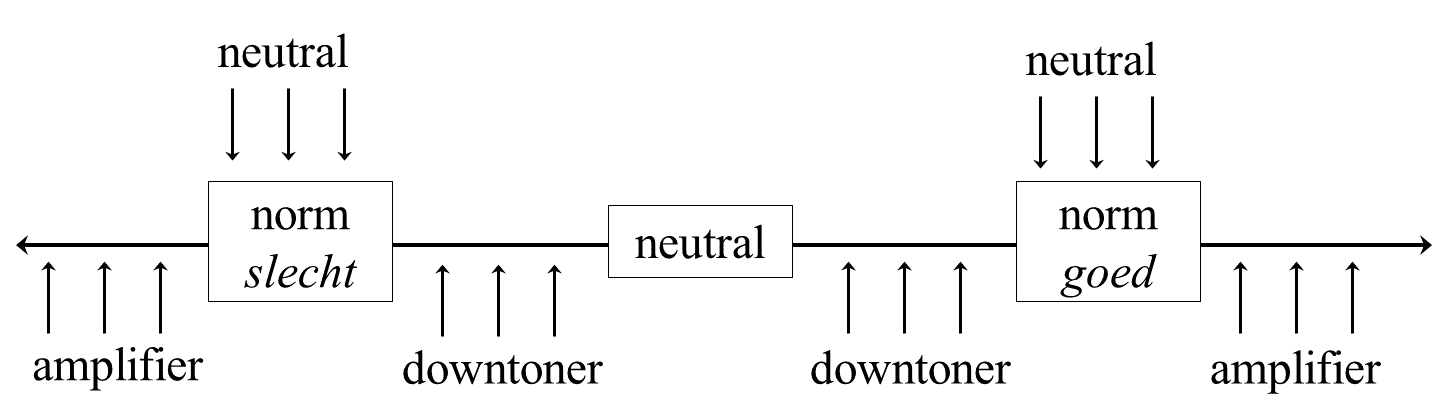

The implied norm can be represented as an interval of the range indicated by the two scalar adjectives, as in (7). The downtoners refer to a particular point or interval on the implied scale between the neutral zone and the norm, while the amplifiers refer to a point/interval on the opposite side of the norm. The neutral modifiers indicate a point/interval at or near the norm.

| Scale of goodness |

|

The semantic effect of using a downtoner can be expressed by the semantic representations introduced in Section 25.1.1; cf. example (5). First, suppose that of two degrees d1 and d2, d1 is lower than d2 (d1 < d2) if d1 is closer to the neutral zone than d2. Second, let us represent the implied norm as dn. Now consider the examples in (8), along with their semantic representations in the primed examples.

| a. | Jan is zeer slecht. | amplifier | |

| Jan is very bad |

| a'. | ∃d [slecht (Jan,d) & d > dn] |

| b. | Jan is vrij slecht. | downtoner | |

| Jan is rather bad |

| b'. | ∃d [slecht (Jan,d) & d < dn] |

| c. | Jan is min of meer slecht. | neutral | |

| Jan is more or less bad |

| c'. | ∃d [slecht (Jan,d) & d ≈ dn] |

The semantic effect of the amplifier zeervery can now be described by the semantic representation in (8a'). This representation is similar to the semantic representation in (5a), with the addition of the part (d > dn), which expresses that the degree to which Jan is bad exceeds the implied norm. The semantic contribution of the downtoner vrijrather is expressed in the representation in (8b') by the part (d < dn), which expresses that the degree to which Jan is bad is lower than the implied norm. Finally, the contribution of the neutral degree modifier min of meermore or less is expressed by adding the part that states that the degree to which Jan is bad is approximately equal to the norm (d ≈ dn).

Degree modifiers can be of different categories, viz. AP, NP, or PP. Their categorial status may be clear from their internal structure, from their morphological behavior, or from the fact that they can also be used in positions typical of APs, NPs, or PPs. For example, the degree modifier ernstigseriously in (9a) is an adjective, as shown by the following two facts. First, ernstig can be modified by the degree modifiers zeervery and vrijrather: these are never used to modify a noun (cf. (9a&b)). Second, ernstig can undergo comparative formation, as in (9a'). Given the presence of the indefinite determiner eena and the possibility of adding an attributively used adjective such as kleinlittle, the degree modifier een beetjea bit in (9b) clearly has the internal composition of a noun phrase. The presence of the preposition in in example (9c) clearly indicates that the degree modifier in hoge mateto a high degree is a PP.

| a. | Jan is | (zeer/vrij) | ernstig | ziek. | |

| Jan is | very/rather | seriously | ill |

| a'. | Jan is ernstiger | ziek | dan Peter. | |

| Jan is more seriously | ill | than Peter |

| b. | Jan is een | (klein/*zeer/*vrij) | beetje | ziek. | |

| Jan is a | little/very/rather | bit | ill |

| c. | Jan is in hoge mate | ziek. | |

| Jan is to high degree | ill | ||

| 'Jan is severely ill.' | |||

Nevertheless, many degree modifiers cannot easily be assigned to one of the three categories AP, NP, or PP, because the possibilities of modifying them are themselves limited, and their morphological behavior and internal structure provide few clues. Following tradition, we call these degree modifiers adverbs, although they may actually be regular adjectives; cf. Chapter 30.

The remainder of this section is organized as follows. We begin the discussion of degree modification with the amplifiers (Subsection I), downtoners (Subsection II), and neutral degree modifiers (Subsection III). This is followed by a discussion of the interrogative degree modifier hoehow in Subsection IV. The exclamative marker wat, a category in its own right, is discussed in Subsection V.

Amplifiers scale upward from a tacitly assumed norm. For a degree modifier to be characterized as an amplifier, we should be able to infer from the combination degree modifier + adjective that the state described by the adjective exceeds the assumed norm. This can be tested by placing the modified scalar adjective in the frame shown in (10a), where co-indexing expresses that the subject of the first clause is coreferential with the pronominal subject of the second clause. The element zelfseven requires the following AP to scale upward: the degree di implied by the second clause must be higher than the norm dn (di > dn). If the result is acceptable, we are dealing with an amplifier; if not, the modifier is probably a downtoner or a neutral degree adverbial. This is illustrated for the amplifier zeervery in (10b), and for the downtoner vrijrather in (10c).

| a. | NPi is A; | pronouni | is zelfs | MODIFIER | A | |

| NP is A | ## | is even | ## | ## | ||

| b. | Jan is aardig; | hij | is zelfs | zeer | aardig. | |

| Jan is nice | he | is even | very | nice | ||

| c. | $ | Jan is aardig; | hij | is zelfs | vrij | aardig. |

| Jan is nice | he | is even | rather | nice |

The use of the number sign in (10c) indicates that zelfs vrij aardig is not unacceptable as such: it can be used in contexts such as Jan is niet onaardig; hij is zelfs vrij aardigJan is not unkind; in fact he is even quite nice, in which case zelfs indicates that Jan is not located in the neutral zone of the scale of goodness, but in the lower part of the range denoted by goed. The following subsections discuss the categories that can act as amplifiers. Apart from adverbs, amplifiers belong to the categories AP and PP.

There are a limited number of amplifiers for which it is not easy to determine whether they are APs, NPs, or PPs; we will refer to these as adverbs for convenience. Some examples are given in (11).

| a. | heel goed | ‘very good’ |

| b. | hogelijk verbaasd | ‘highly amazed’ |

| c. | hoogst interessant | ‘most interesting’ |

| d. | uitermate gevaarlijk | ‘extremely dangerous’ |

| e. | uiterst belangrijk | ‘extremely important’ |

| f. | zeer zacht | ‘very soft’ |

The adverb heelvery is special in that, at least in colloquial speech, it optionally gets the attributive -e ending when it modifies an attributive adjective ending in -e. That this is excluded with the other adverbs in (11) is shown in (12). Subsection B will show that the adjectival amplifier erg is similar to heel in this respect.

| a. | een | heel/hel-e | aardig-e | jongen | |

| a | very | nice | boy |

| b. | een | uiterst/*uiterst-e | aardig-e | jongen | |

| an | extremely | nice | boy |

| c. | een | zeer/*zeer-e | zachte | handdoek | |

| an | extremely | soft | towel |

The primeless examples in (13) show that the adverbs in (11) cannot be modified themselves; the examples in (20) from Subsection B below will show that the adverbs differ from the adjectival amplifiers in this respect. The primed examples show that the adverbs in (11) are not usually used in negative clauses either (with the exception of denials of presuppositions).

| a. | * | zeer | heel | goed |

| very | very | good |

| a'. | Dat boek | is (?niet) | heel | goed. | |

| that book | is not | very | good |

| b. | * | zeer | hogelijk | verbaasd |

| very | highly | amazed |

| b'. | Jan is (*niet) | hogelijk | verbaasd. | |

| Jan is not | highly | amazed |

| c. | * | zeer | hoogst | interessant |

| very | most | interesting |

| c'. | Dat artikel | is (*niet) | hoogst | interessant. | |

| that article | is not | most | interesting |

| d. | * | heel | uitermate | gevaarlijk |

| very | extremely | dangerous |

| d'. | Vuurwerk | is (*niet) | uitermate | gevaarlijk. | |

| Firework | is not | extremely | dangerous |

| e. | * | heel | uiterst | belangrijk |

| very | extremely | important |

| e'. | Het probleem | is (*niet) | uiterst belangrijk. | |

| the problem | is not | extremely important |

| f. | * | heel | zeer | zacht |

| very | very | soft |

| f'. | De deken | is (?niet) | zeer zacht. | |

| the blanket | is not | very soft |

The modifiers typischtypically, specifiekspecifically and echttruly can also belong to the group of amplifying adverbs, although they have a special property in that they combine with relational adjectives, not with scalar set-denoting adjectives (cf. *typisch groottypically big). Although relational adjectives do not usually occur in predicative position, the addition of these amplifiers generally makes it possible; the modified adjective is then construed as referring to some typical property or set of properties of the modified noun; cf. Section 23.3.3. For instance, the examples in (14) express that the cheese in question has (unspecified) properties that are characteristic of cheese produced in the Netherlands.

| a. | een | typisch Nederlandse | kaas | |

| a | typically Dutch | cheese |

| b. | Deze kaas | is typisch | Nederlands. | |

| this cheese | is typically | Dutch |

The group of adjectival amplifiers is extremely large and seems to be an open class to which new forms can easily be added. The adjectival amplifiers can be divided into two groups based on whether they have retained their original meaning.

The adjectival amplifiers in (15) are similar to the adverbs in (11) in that they only have an amplifying effect; their original meaning, which is given in the glosses, has more or less disappeared.

| a. | knap | moeilijk | |

| handsomely | difficult |

| e. | verschrikkelijk | geinig | |

| terribly | funny |

| b. | flink | sterk | |

| firmly | strong |

| f. | vreselijk | aardig | |

| terribly | nice |

| c. | oneindig | klein | |

| infinitely | small |

| g. | waanzinnig | goed | |

| insanely | good |

| d. | ontzettend | aardig | |

| terribly | nice |

| h. | geweldig | lief | |

| tremendously | sweet |

Like the adverbs in (11), the amplifiers in (15) cannot themselves be amplified, nor can they occur in negative clauses, as shown in (16).

| a. | * | heel | vreselijk | geinig |

| very | terribly | funny |

| a'. | Jan is (*niet) | vreselijk | geinig. | |

| Jan is not | terribly | funny |

| b. | * | erg | waanzinnig | goed |

| very | insanely | good |

| b'. | Jan is (*niet) | waanzinnig | goed. | |

| Jan is not | insanely | good |

We can probably include the evaluative adjectives in (17) in the same group as the adjectives in (15): the examples in (18) show that they also cannot be amplified or occur in negative clauses.

| a. | jammerlijk | slecht | |

| deplorably | bad |

| c. | verduiveld | goed | |

| devilishly | good |

| b. | verdomd | leuk | |

| damned | nice |

| d. | verrekt | moeilijk | |

| damned | difficult |

| a. | * | erg jammerlijk slecht |

| very deplorably bad |

| a'. | Dat boek | is | (*niet) | jammerlijk | slecht. | |

| that book | is | not | deplorably | bad |

| b. | * | zeer | verdomd | leuk |

| very | damned | nice |

| b'. | Dat boek | is | (*niet) | verdomd | leuk. | |

| that book | is | not | damned | nice |

Note that (17d) is somewhat special in that the amplifier verrekt can be intensified by the addition of an -e ending, as shown in (19a). Since the AP verrekte moeilijk is used in predicative position, the schwa ending of verrekte obviously cannot be an attributive ending; in fact, the use of the additional schwa has a degrading effect when the AP is used in attributive position, as shown in (19b).

| a. | Dit | is verrekte | moeilijk. | |

| this | is damned | difficult | ||

| 'This is extremely difficult.' | ||||

| b. | die | verrekt/*?verrekte | moeilijke | opgave | |

| that | damned | difficult | exercise | ||

| 'that extremely difficult exercise' | |||||

Note that verrekt is used not only as a degree modifier, but also as an evaluative attributive modifier, as in die verrekte opgavethat damned exercise; cf. A1.3.5. It may be that the degree reading of verrekte in (19b) is disfavored by the competition of the fully acceptable stacked reading “that damned, difficult exercise”.

The adjectival amplifiers of the second group have more or less retained the meaning they have in attributive or predicative position. As a result, it is sometimes quite difficult to give a satisfactory translation in English. Some examples are given in (20) and (21).

| a. | druk | bezig | |

| busily | engaged |

| c. | hard | nodig | |

| badly | needed |

| b. | erg | ziek | |

| badly | ill |

| d. | hartstochtelijk | verliefd | |

| passionately | in.love |

| a. | absurd | klein | |

| absurdly | small |

| f. | buitengewoon | groot | |

| extraordinarily | big |

| b. | afgrijselijk | lelijk | |

| atrociously | ugly |

| g. | enorm | groot | |

| enormously | big |

| c. | behoorlijk | dronken | |

| quite | drunk |

| h. | extra | goedkoop | |

| extra | cheap |

| d. | belachelijk | groot | |

| absurdly | big |

| i. | ongelofelijk | mooi | |

| unbelievably | handsome |

| e. | bijzonder | groot | |

| especially | big |

| j. | opmerkelijk | mooi | |

| strikingly | beautiful |

The use of the adjectival amplifiers in (20) and (21) is highly productive, although it should be noted that they cannot be used to modify an adjective of the same form. This is illustrated in (22).

| a. | erg/*bijzonder | bijzonder | |

| very | special |

| b. | bijzonder/*erg | erg | |

| very | bad |

Note that there are also adjectival modifiers that have fully retained their lexical meaning, but whose main function is not amplification; cf. Section 30.5. Some examples are given in (23).

| a. | De tafel | is onherstelbaar | beschadigd. | |

| the table | is irreparably | damaged |

| b. | De soep | is lekker zout. | |

| the soup | is tastily salty |

The main semantic difference between the two sets of amplifiers in (20) and (21) is that the amplification is less strong in the former than in the latter: the amplifiers in (20) express that the state denoted by the modified adjective holds to a high degree, while the amplifiers in (21) express that the state holds to an extremely high or even the highest degree. In other words, the amplifiers in (20) are more or less on a par with the prototypical amplifier zeervery, while the amplifying force of the amplifiers in (21) exceeds the amplifying force of zeer. This can be made clear by the frame in (24a), where the element zelfseven requires the second AP to scale upward with respect to the first; cf. the discussion of (10). Since the amplifiers in (20) cannot be used felicitously in this frame, we can conclude that their amplifying force does not exceed the amplifying force of zeer. On the other hand, the fact that the amplifiers in (21) can be used successfully in this frame shows that their amplifying force is stronger than that of zeer. The use of the number sign again indicates that the string zelfs erg ziek can be used in other contexts.

| a. | NPi is zeer A; NP is very | pronouni | is zelfs is even | MODIFIER | A. | |

| b. | $ | Jan is zeer ziek. Jan is very ill | Hij he | is zelfs is even | erg very | ziek. ill |

| c. | Gebouw B is zeer lelijk. building B is very ugly | Het it | is zelfs is even | afgrijselijk atrociously | lelijk. ugly |

This difference between the amplifiers in (20) and (21) is also reflected in their gradability. The examples in (25) show that the amplifiers in (20) can themselves be amplified by the adverbs in (11) and undergo comparative/superlative formation.

| a. | een | heel | erg | zieke | jongen | |

| a | very | very/badly | ill | boy |

| a'. | Jan is erger | ziek | dan Peter. | |

| Jan is more.very/worse | ill | than Peter |

| a''. | Jan is het ergst | ziek. | |

| Jan is the worst | ill |

| b. | Een nieuwe computer | is heel hard | nodig. | |

| a new computer | is very badly | needed |

| b'. | Een nieuwe computer | is harder | nodig | dan een nieuwe printer. | |

| a new computer | is more.badly | needed | than a new printer |

| b''. | Een nieuwe computer | is het hardst | nodig. | |

| a new computer | is the most.badly | needed |

The examples in (26), on the other hand, show that amplification of the amplifiers in (21) is excluded and that the same holds for comparative and superlative formation.

| a. | *? | een | heel afgrijselijk | lelijk | gebouw |

| a | very atrociously | ugly | building |

| a'. | * | Gebouw B | is afgrijselijker | lelijk | dan gebouw C. |

| building B | is more atrociously | ugly | than building C |

| a''. | * | Gebouw B | is het afgrijselijkst | lelijk. |

| building B | is the most atrociously | ugly |

| b. | * | Dit boek | is uiterst opmerkelijk | mooi. |

| this book | is extremely strikingly | beautiful |

| b'. | * | Dit boek | is opmerkelijker | mooi | dan dat boek. |

| this book | is more strikingly | beautiful | than that book |

| b''. | * | Dit boek | is het opmerkelijkst | mooi. |

| this book | is the most strikingly | beautiful |

Apparently, their ultra-high degree reading, triggered by these adverbs, blocks further amplification. Note that the unacceptability of the examples in (26) is not due to some idiosyncratic property of the adjectives; modification and comparative/superlative formation are both possible in the attributive and predicative use of these adjectives, as shown in (27).

| a. | een | heel afgrijselijk | gebouw | |

| a | very atrocious | building |

| a'. | Gebouw B | is afgrijselijker | dan gebouw C. | |

| building B | is more atrocious | than building C |

| a''. | Gebouw B | is het afgrijselijkst. | |

| building B | is the most atrocious |

| b. | een | uiterst opmerkelijk | boek | |

| an | extremely remarkable | book |

| b'. | Dit boek | is opmerkelijker | dan dat boek. | |

| this book | is more remarkable | than that book |

| b''. | Dit boek | is het opmerkelijkst. | |

| this book | is the most remarkable |

Finally, the amplifying force of the amplifiers in (20) can often be increased by reduplication; this is categorically excluded for the amplifiers in (21). This is shown in (28).

| a. | Een nieuwe computer | is hard, | hard | nodig. | |

| a new computer | is badly | badly | needed | ||

| 'A new computer is very badly needed.' | |||||

| b. | * | Dit boek | is opmerkelijk, | opmerkelijk | mooi. |

| this book | is strikingly | strikingly | beautiful |

Although there seem to be differences between the individual members of the two sets of amplifiers in (20) and (21), they all seem to be possible in negative clauses; cf. also Section 25.3, sub I. This is shown in (29) and (30).

| a. | Jan is niet | erg | groot. | |

| Jan is not | very | tall |

| b. | Jan is niet | bepaald | hartstochtelijk verliefd. | |

| Jan is not | exactly | passionately in.love |

| a. | Jan is niet | bijzonder/buitengewoon | groot. | |

| Jan is not | especially/extraordinarily | tall |

| b. | Jan is niet | opmerkelijk | mooi. | |

| Jan is not | strikingly | beautiful |

The amplifier ergvery is special because in colloquial speech it can optionally receive an attributive -e ending when modifying an attributive adjective ending in -e; we have seen that the same is possible with the adverb heel in (12a). This is not easily possible with the other adjectival amplifiers, although they do occur in speech. This contrast is illustrated in (31); note that enorme is perfectly acceptable when interpreted as an attributive adjective modifying the noun phrase donkere kamer, i.e. under the interpretation “an enormous/huge dark room”. We refer the reader to Verdenius (1939) and Van der Meulen (2019) for further examples.

| a. | een | erg/erg-e | donker-e | kamer | |

| a | very | dark | room |

| b. | een | behoorlijk/??behoorlijk-e | zwar-e | klus | |

| a | pretty | difficult | job |

| c. | een | enorm/#enorm-e | donker-e | kamer | |

| an | extremely | dark | room |

In the combination of the adverb heelvery and the adjectival modifier erg, the adverb must precede the adjective, which produces the following inflectional possibilities; the percentage sign in (32b) indicates that speakers seem to differ in their judgments on this example.

| a. | een | heel | erg | donker-e | kamer | |

| a | very | very | dark | room |

| b. | % | een heel erg-e | donker-e kamer |

| c. | een hel-e erg-e | donker-e kamer |

| d. | * | een hel-e erg donker-e kamer |

Noun phrases do not occur as amplifiers, with the possible exception of exclamative wathow, which will be discussed in Subsection V.

The prepositional phrase in ... mateto a ... degree, where the dots indicate an adjective modifying the noun matedegree, can also be used as a degree modifier. The (a)-examples in (33) show that, depending on the nature of the adjective, the PP is interpreted either as an amplifier or as a downtoner. Another PP that can be used as an amplifier is given in (33b).

| a. | in hoge mate | besmettelijk | amplifier | |

| in high measure | contagious | |||

| 'highly contagious' | ||||

| a'. | in beperkte mate | beschikbaar | downtoner | |

| in limited measure | available | |||

| 'sparsely available' | ||||

| b. | bij uitstek geschikt | amplifier | |

| 'suitable par excellence' |

The use of coordinated prepositions in (34a&b) is noteworthy; cf. also the examples in (37a) in Subsection E below. The isolated preposition in in (34a') can also be used to express amplification, in which case it must be heavily accented (indicated by small caps); (34b') shows that this alternation is not always possible.

| a. | een in en in schone was | |

| 'a through and through clean laundry' |

| a'. | een in schone was | |

| 'a thoroughly clean laundry' |

| b. | een door en door bedorven kind | |

| 'a through and through spoiled child' |

| b'. | * | een door bedorven kind |

Finally, the examples in (35) show that there are a number of compound-like adverbs whose first member seems to be a preposition.

| a. | boven: bovengemiddeld intelligent ‘more than averagely intelligent’; bovenmate mooi ‘extraordinarily beautiful’ |

| b. | buiten: buitengemeen knap ‘unusually handsome’; buitengewoon groot ‘extraordinarily large’ |

| c. | over: overmatig ijverig ‘overly diligent’ |

The preposition over can also have an amplifying effect when used as the first member of a P+A compound, sometimes even expressing that a certain standard value or norm has been exceeded; some examples from the Van Dale dictionary are overactiefhyperactive, overmooivery beautiful, overheerlijkdelicious, and overstilvery/too calm.

Amplification does not have to involve the use of an amplifier, but can also be achieved in several other ways. We discuss these briefly in the following subsections.

Some adjectives are morphologically amplified, as in the case of complex adjectives like beeldschoongorgeous (lit.: statue-beautiful), doodengreally scary (lit.: death-scaring), oliedomextremely stupid (lit.: oil-stupid) and beregoedterrific (lit.: bear-good); the first part of the compound expresses the amplification. As shown in (36), these complex adjectives cannot be modified by additional downtoners or amplifiers.

| a. | een | (*vrij/*erg) | beeldschoon | schilderij | |

| a | rather/very | gorgeous | painting |

| b. | een | (*nogal/*ontzettend) | doodenge | film | |

| a | rather/terribly | really.scary | movie |

| c. | * | een | (*vrij/”zeer) | oliedomme | jongen |

| a | rather/very | extremely.stupid | boy |

| d. | * | een | (*nogal/*zeer) | beregoed | optreden |

| a | rather/very | terrific | act |

However, further amplification can often be obtained by reduplication of the first morpheme, as in (37). If the first morpheme of the compound is monosyllabic, the use of the coordinator enand seems to be preferred. If the first morpheme is disyllabic, the reduplicated morphemes can be separated by a comma intonation. We are dealing with tendencies here, as can be seen by the fact that all the forms in (37) can be found on the internet.

| a. | Dat schilderij is beeld- en beeldschoon. | ?beeld-, beeldschoon | |

| 'That painting is uper gorgeous.' |

| b. | Die film is dood- en doodeng. | ?dood-, doodeng | |

| 'That movie is really scary.' |

| c. | Die jongen is olie-, oliedom. | ?olie- en oliedom | |

| 'That boy is extremely stupid.' |

| d. | Dat optreden was bere-, beregoed. | ?bere- en beregoed | |

| 'That performance was terrific.' |

The compounds in (36) are generally idiomatic; the first member of the compound cannot be used productively to form intrinsically amplified adjectives. No other compounds can be formed with the amplifying morphemes in (36): *olieschoon, *doodschoon, *bereschoon, *beelddood, #oliedood, *beredood, *beelddom, *dooddom, *beredom, *beeldgoed, *doodgoed, *oliegoed. It is usually assumed that the possible combinations are listed in the lexicon as separate lexical items. It should be noted, however, that around the year 2000 the amplifying affixes dood- and bere- suddenly became quite popular. As a result, some of the starred examples are now easily found on the internet, and may indeed have entered the lexicon as lexicalized forms for a large group of speakers. More recently, the amplifying prefixes super-, ultra-, and mega- have become quite popular, showing that the morphological process of amplification is an easy locus of language variation/change.

The primeless cases in (38) show that amplification can also be expressed by the meer dan A construction, which involves the comparative form of the adjective veelmuch/many. The primed examples show that the comparative form of weiniglittle/few cannot enter into a similar construction.

| a. | Jan is meer | dan tevreden. | |

| Jan is more | than satisfied |

| a'. | *? | Jan is minder | dan tevreden. |

| Jan is less | than satisfied |

| b. | Dit boek | is meer | dan | alleen | maar | aardig. | |

| this book | is more | than | just | prt | nice |

| b'. | * | Dit boek | is minder | dan aardig. |

| this book | is less | than nice |

It is not entirely clear what the internal structure of the predicative phrases in the primeless examples is. Normally it is the comparative that functions as the semantic head of the construction, which is clear from the fact that the dan-phrase can be omitted: cf. Jan is aardiger (dan Peter)Jan is nicer (than Peter). In the primed examples in (38), on the other hand, it is the adjective in the dan-phrase that acts as the semantic head, which is clear from the fact that omitting the dan-phrase yields an uninterpretable result. Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that the semantic difference should be reflected in the syntactic structure of the predicative phrase; we leave this to future research.

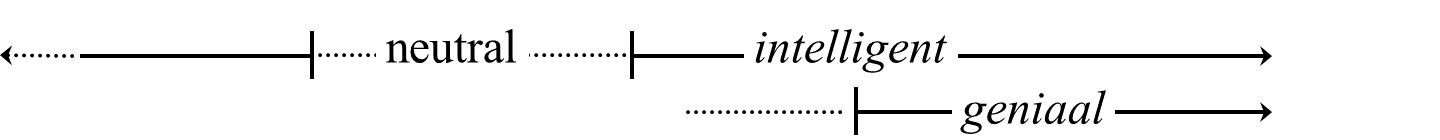

Finally, it should be noted that the adjectives in the primed examples in (39) express more or less the same meaning as the comparative meer dan A construction in the primeless examples.

| a. | meer | dan intelligent | |

| more | than intelligent |

| a'. | geniaal | |

| brilliant |

| b. | meer | dan goed | |

| more | than good |

| b'. | uitstekend/uitmuntend | |

| excellent |

| c. | meer | dan | alleen | maar | lekker | |

| more | than | just | prt | tasty |

| c'. | zalig/verrukkelijk | |

| delicious |

This shows that some scales can be relevant for more than one adjective, as shown in (40) for intelligent and geniaal in (39a).

| Scale of intelligence |

|

The ultra-high degree adjectives in the primed examples in (39) can be amplified, but this easily leads to an ironic or hyperbolic connotation; modification by a downtoner often does not produce a very felicitous result either, and the same goes for comparative/superlative formation. The forms marked with a percentage sign can be found on the internet; the comparative and superlative forms are relatively common in religious contexts, suggesting that they belong to the more formal register.

| example | amplification | downtoning | comparative | superlative |

| geniaal brilliant | %zeer geniaal very brilliant | ??vrij geniaal rather brilliant | ??genialer more brilliant | ??het geniaalst the most brilliant |

| uitstekend excellent | %zeer uitstekend very excellent | *vrij uitstekend rather excellent | *uitstekender more excellent | *het uitstekendst the most excellent |

| zalig delicious | %zeer zalig very delicious | *vrij zalig rather delicious | %zaliger more delicious | %het zaligst the most delicious |

The equative construction in (42a) compares two properties: it states that the length and width of the table are equal. Note that this example does not imply that the table in question is long or wide; it may be quite short and narrow. This shows that the measure adjectives langlong and breedwide; are neutral in the sense of Section 23.3.2.2, sub ID. This is also supported by the fact that the use of the non-neutral forms kortshort and smallnarrow in (42b) leads to a marked result.

| a. | De tafel | is even | lang | als breed. | |

| the table | is as | long | as wide |

| b. | ?? | De tafel | is even | kort | als smal. |

| the table | is as | short | as narrow |

However, if we compare two adjectives of which at least one is not a measure adjective, the implication is that both properties exceed the neutral norm: (43a) implies that Jan is both quite old and quite cunning, and (43b) implies that Jan is both quite intelligent and quite crazy. The constructions in (43) are thus amplifying in nature. See Section 26.1.4 for further discussion of these constructions.

| a. | Jan is even | doortrapt | als | oud. | |

| Jan is as | cunning | as | old |

| b. | Jan is even | intelligent | als gek. | |

| Jan is as | intelligent | as crazy |

The comparative constructions in (44) both express that Jan is taller than Marie. However, example (44a) need not express that Jan is tall; he can actually be quite short. Similarly, (44b) need not express that Marie is short; she can be quite tall.

| a. | Jan is groter | dan/als Marie. | |

| Jan is taller | than Marie |

| b. | Marie is kleiner | dan/als Jan. | |

| Marie is smaller | than Jan |

If we add the adverb nogeven to the examples in (44), as in (45), the meaning changes radically. Example (45a) expresses that both Jan and Marie are (quite) tall, and (45b) expresses that both Marie and Jan are (quite) short. In other words, the addition of nog has an amplifying effect.

| a. | Jan is nog | groter | dan/als Marie. | |

| Jan is even | taller | than Marie |

| b. | Marie is nog | kleiner | dan/als Jan. | |

| Marie is even | smaller | than Jan |

Recall that the comparative form of the ultra-high degree adjective geniaalbrilliant is usually somewhat marked, as indicated in (46a). This markedness disappears completely when the comparative is preceded by nog, as in (46b).

| a. | ?? | Jan is genialer | dan/als Marie. |

| Jan is more.brilliant | than Marie |

| b. | Jan is nog genialer | dan/als Marie. | |

| Jan is even more.brilliant | than Marie |

The examples in (45) and (46b) suggest that nog selects a high or ultra-high degree adjective to amplify its degree to an even more exceptional level.

An amplifying effect can also be obtained by accentuating (and lengthening) the adjective, as in the primeless examples of (47), an effect that can even be enhanced by reduplication of the adjective, as in the primed examples. The (a)-examples are complementives, the (b)-examples are attributive adjectives, and the (c)-examples are adverbially used adjectives.

| a. | Dat boek is mooi! | predicative | |

| that book is beautiful |

| a'. | Dat boek is mooi, MOOI! |

| b. | Hij | heeft | een | groot | huis | gekocht! | attributive | |

| he | has | a | big | house | bought |

| b'. | Hij heeft een groot, GROOT huis gekocht! |

| c. | Jan heeft | hard | gewerkt! | adverbial | |

| Jan has | hard | worked | |||

| 'Jan has worked hard!' | |||||

| c'. | Jan heeft hard, HARD gewerkt! |

The examples in (47) are exclamative; other exclamative constructions can have a similar amplifying effect. This is illustrated in (48) for exclamative constructions with the exclamative marker wat, which will be discussed in more detail in Subsection V.

| a. | Wat | is dat boek | mooi! | predicative | |

| what | is that book | beautiful |

| b. | Wat | is dat | een groot huis! | attributive | |

| what | is that | a big house |

| c. | Wat | heeft | Jan hard gewerkt! | adverbial | |

| what | has | Jan hard worked |

The same is true for the exclamative dat constructions in (49). In these constructions, the (phrase containing the) adjective is immediately followed by a clause introduced by the complementizer datthat with the finite verb in clause-final position. The construction as a whole cannot be used as a clausal constituent.

| a. | Mooi | dat | dat boek | is! | predicative | |

| beautiful | that | that book | is |

| b. | Een groot huis | dat | hij | gekocht | heeft! | attributive | |

| a big house | that | he | bought | has |

| b'. | Een aardige vader | dat/*die | hij heeft! | attributive | |

| a nice father | that/who | he has |

| c. | Hard | dat Jan gewerkt heeft! | adverbial | |

| hard | that Jan worked has |

For completeness, note that dat is not a relative pronoun in the attributive (b)-examples; the neuter relative pronoun dat cannot take a non-neuter noun phrase such as een aardige vadera nice father as its antecedent; furthermore, replacing dat with the neuter relative form die leads to unacceptability.

Downtoners scale downward from a tacitly assumed norm. For a degree modifier to be characterized as a downtoner, we should be able to infer from the combination of degree modifier + adjective that the state described by the adjective does not hold to the extent of the implicit norm. This can be tested by placing the modified scalar adjective in the frame in (50a), where the co-indexation expresses that the subject of the first clause is coreferential with the pronominal subject of the second clause. The phrase in ieder gevalin any case requires the following AP to scale downward: the degree di implied by the second clause must be lower than the norm dn (di < dn). If the result is acceptable, we are dealing with a downtoner; if this is not possible, the modifier is most likely an amplifier or a neutral degree adverbial. This is illustrated for the downtoner vrijrather in (50b) and for the amplifier zeervery in (50c).

| a. | NPi is A; NP is A | Pronouni | is in ieder geval is in any case | MODIFIER | A | |

| b. | Jan is aardig; Jan is nice | hij he | is in ieder geval is in any case | vrij rather | aardig. nice | |

| c. | $ | Jan is aardig; Jan is nice | hij he | is in ieder geval is in any case | zeer very | aardig. nice |

On the whole, there seem to be fewer options for downtoning than for amplification: amplifiers are usually adverbs or noun phrases; the use of PPs is limited, and adjectival downtoners are extremely rare, perhaps non-existent.

There are a limited number of adverbs that can be used as downtoners. Some examples are given in (51). Like adverbial amplifiers, adverbial downtoners cannot be modified by a degree modifier or undergo comparative/superlative formation.

| a. | enigszins | nerveus | |

| somewhat | nervous |

| b. | lichtelijk | overdreven | |

| somewhat | exaggerated |

| c. | tamelijk | pretentieus | |

| fairly | pretentious |

| d. | vrij | saai | |

| rather | boring |

Adjectival downtoners seem to be rare; adjectival amplifiers certainly outnumber them. This is also clear from the fact that the adjectival amplifiers discussed in Subsection I have no antonyms; cf. the lists in (20) and (21). A possible exception is the amplifier knapquite (not mentioned earlier), which seems to have the downtoner aardigfairly as its antonym; the cases in (52a&b) show that, at least for some speakers, both are preferred with negatively valued adjectives. However, example (52b') shows that the correspondence does not hold completely: examples such as aardig actief are possible and certainly feel less marked than examples such as knap actief. Obviously, the contrast in (52a&b) does not hold for all speakers, since most of the examples in (52b) can be found on the internet. For this reason we have marked them with a percentage sign.

| a. | Hij | is knap/aardig | brutaal/moeilijk/lastig/ongehoorzaam. | |

| he | is quite/fairly | cheeky/difficult/troublesome/disobedient |

| b. | % | Hij | is knap/aardig | beleefd/makkelijk/eenvoudig/gehoorzaam. |

| he | is quite/fairly | polite/easy/simple/obedient |

| b'. | Hij | is aardig/%knap | actief/rijk/verbeterd. | |

| he | is fairly/quite | active/rich/improved |

The acceptability of the instances in (53) clearly shows that the amplifying force of knap exceeds the amplifying force of aardig.

| a. | Jan is aardig brutaal. | Hij | is zelfs | knap | brutaal. | |

| Jan is fairly cheeky | he | is even | quite | cheeky |

| b. | Jan is knap brutaal. | Hij | is in ieder geval | aardig brutaal. | |

| Jan is quite cheeky | he | is in any case | fairly cheeky |

However, it is not entirely clear whether aardig is really a downtoner: Dutch speakers seem to differ in their judgments on the downtoner/amplifier test in (54), suggesting that aardig is not a downtoner but a neutral degree modifier; cf. Subsection III.

| Jan is brutaal. |

| a. | % | Hij is in ieder geval aardig brutaal. |

| b. | % | Hij is zelfs aardig brutaal. |

Another possible example of an adjectival downtoner is redelijkreasonably. According to some speakers, this degree modifier prefers a positively valued adjective, although again it should be noted that examples like those in (55b) can be found on the internet.

| a. | redelijk | beleefd/makkelijk/eenvoudig/gehoorzaam | |

| reasonably | polite/easy/simple/obedient |

| b. | % | redelijk | brutaal/moeilijk/lastig/ongehoorzaam |

| reasonably | cheeky/difficult/troublesome/disobedient |

If the modified adjective is not inherently positively or negatively valued, the use of redelijk can have the effect of assigning a positive value to the adjective. This can be illustrated by the fact that the felicitousness of the examples in (56) depends on the context: if the speaker is looking for a big TV, he would most likely use (56a) to indicate that the TV is close to what he is looking for; on the other hand, if he is looking for a small appliance, he would use (56b) to refer to a TV that is more or less the right size.

| a. | Die televisie | is redelijk | groot. | |

| that television | is reasonably | big | ||

| 'That TV set is fairly large.' | ||||

| b. | Die televisie | is redelijk | klein. | |

| that television | is reasonably | small | ||

| 'That TV set is pretty small.' | ||||

As shown in (57a), redelijk seems to pass the downtoner test. However, since the use of zelfseven is not as marked as one would expect in the case of a downtoner, it may be that we are again dealing with a neutral degree modifier. This would also be consistent with the examples in (57b&c), which show that the downtoning/amplifying force of redelijk is exceeded by that of unambiguous downtoners and amplifiers like vrijquite and ergvery.

| a. | Die televisie | is groot. | Hij | is in ieder geval/?zelfs | redelijk groot. | |

| that television | is big | he | is in any case/even | reasonably big | ||

| 'That TV set is large. It is at least/even fairly large.' | ||||||

| b. | Die televisie | is vrij groot. | Hij | is zelfs redelijk groot. | |

| that television | is quite big | he | is even reasonably big |

| c. | Die televisie | is erg groot. | Hij | is in ieder geval | redelijk groot. | |

| that television | is very big | he | is in any case | reasonably big |

This subsection has discussed two adjectival degree modifiers that may be used as downtoners. However, the evidence for downtoner status is flimsy, and it may well be that these adjectives should rather be classified as neutral degree modifiers.

While noun phrases do not occur as amplifiers (cf. Subsection I), they are possible as downtoners. This holds in particular for the noun phrase een beetjea little in (58); these examples also show that een beetje behaves like a regular noun phrase in that it can be modified by the attributive adjective kleinlittle.

| a. | een | (klein) | beetje | gek | |

| a | little | bit | strange |

| b. | een | (klein) | beetje | verliefd | |

| a | little | bit | in.love |

| c. | een | (klein) | beetje | zout | |

| a | little | bit | salty |

In contrast, the modifiers in (59) cannot occur as regular noun phrases and cannot be modified by e.g. an adjective. The use of the indefinite article eena strongly suggests that they are still noun phrases, which is also supported by the fact that they have a diminutive form.

| a. | een | tikkeltje | saai | |

| a | tiny.bit | boring |

| b. | een | ietsje | kouder/?koud | |

| a | little.bit | colder/cold |

| c. | een | (ietsie)pietsie | kouder/?koud | |

| a | tiny.bit | colder/cold |

The element (iet)watsomewhat in (60a) should probably also be seen as a nominal downtoner; cf. Subsection V for a discussion of the so-called exclamative modifier wat. The same goes for een weinig in (60b), which has an archaic flavor.

| a. | wat/ietwat | vreemd | |

| somewhat | strange |

| b. | Jan is een weinig | verwaand/onzeker. | |

| Jan is a little | vain/insecure |

The use of nominal downtoners often has a negative connotation when used with an adjective in the positive degree. As shown in (61a), they combine easily with negatively valued adjectives, but not with positively valued adjectives. When they are used with a positively or neutrally valued adjective, the adjective phrase may receive a negative value: the cases in (61b) express that the speaker does not appreciate the actual temperature in the room. This negative connotation can be strengthened by adding the particle wel.

| a. | Hij | is (wel) | een beetje | vervelend/??aardig. | |

| he | is wel | a bit | nasty/nice |

| b. | Het | is | (wel) | een beetje | koud/warm | in de kamer. | |

| it | is | wel | a bit | cold/warm | in the room |

Note that these negative connotations are typical of factive, declarative contexts; they are absent in the interrogative and imperative counterparts of the examples in (61); this is illustrated for aardig en warm in (62).

| a. | Is hij | een beetje | aardig? | |

| is he | a bit | nice |

| a'. | Wees | een beetje | aardig! | |

| be | a bit | nice |

| b. | Is het | een beetje | warm | in de kamer? | |

| Is it | a bit | warm | in the room |

| b'. | Maak | het | eens | een beetje | warm! | |

| make | it | prt | a bit | warm |

Finally, note that noun phrases are not only used as downtoning degree adverbials, but are also very common as modifiers of measure adjectives and comparatives; we return to such cases in Section 25.1.3, sub II, and Section 26.3.2, respectively.

The prepositional phrase in ... mateto a ... degree, where the dots indicate the position of an adjective, can also be used as a degree modifier. Depending on the nature of the adjective, the PP is interpreted either as an amplifier or as a downtoner. The latter is the case in (63).

| a. | in geringe mate nieuw | downtoner | |

| 'to a low degree new' |

| b. | in zekere mate nieuw | downtoner, perhaps neutral | |

| 'new to a certain degree' |

| c. | in hoge mate (on)betrouwbaar | amplifier | |

| 'highly (un)reliable' |

With non-derived adjectives, a downtoning effect can also be obtained by adding the suffix -tjes (or one of its allomorphs -jes, -pjes, and -etjes). Some examples are given in (64). These adjectives cannot be used attributively, which may be due to the fact that they are derived by a diminutive suffix followed by the suffix –s, which has been argued to derive adverbs from nouns and adjectives; cf. Corver (2022).

| a. | bleek-je-s ‘a bit pale’ |

| e. | stijf-je-s ‘slightly stiff’ |

| b. | glad-je-s ‘a bit slippery’ |

| f. | stille-tje-s ‘a bit quiet’ |

| c. | fris-je-s ‘a bit cold’ |

| g. | wit-je-s ‘a bit white’ |

| d. | nat-je-s ‘a bit wet’ |

| h. | zwak-jes ‘somewhat feeble’ |

Such formations differ from the intrinsically amplified adjectives in (36) in Subsection IE, such as beeldschoongorgeous and oliedomextremely stupid, in that the addition of a degree modifier is possible. The examples in (65) show that the degree modifier can be either a downtoner or an amplifier, provided that the latter does not indicate an extremely high degree; while amplifiers like heelquite and zeervery are easily possible, those of the type in (21) give rise to at best a marked result.

| a. | nogal/heel/??ontzettend | bleekjes | |

| rather/quite/extremely | pale |

| b. | vrij/zeer/??vreselijk | stilletjes | |

| rather/very/terribly | quiet |

| c. | een beetje/heel/??afgrijselijk | zwakjes | |

| * | a bit/very/*atrociously | feeble |

Finally, the examples in (66) show that downtoners themselves cannot be modified or occur in negative clauses; cf. Section 25.3, sub I, for more discussion of negation. This is to be expected, since amplifiers can only be modified or occur in negative contexts if they are adjectival in nature; cf. Subsection I. The lack of these options can thus be attributed to the fact that there are no adjectival downtoners.

| a. | * | Die jongen | is enigszins | vrij nerveus. |

| that boy | is slightly | rather nervous |

| a'. | * | Die jongen | is vrij | enigszins | nerveus. |

| that boy | is rather | slightly | nervous |

| b. | * | Die jongen | is niet | enigszins/vrij/een beetje | nerveus. |

| that boy | is not | slightly/rather/a bit | nervous |

Subsections I and II discussed two tests for determining whether a degree modifier should be considered an amplifier or a downtoner: if a degree modifier can be placed in the frame in (67a), it is an amplifier; if it can be placed in the frame in (67b), it is a downtoner. The (c)-examples in (67) show that some degree modifiers, such as nogalfairly, cannot easily be placed in either frame; we will call such modifiers neutral degree modifiers.

| a. | NPi is A; pronouni | is zelfs MODIFIER A. | |

| NP is A | is even |

| b. | NPi is A; pronouni | is in ieder geval MODIFIER A. | |

| NP is A | is in any case |

| c. | ?? | Jan is aardig; | hij | is zelfs | nogal aardig. |

| Jan is nice | he | is even | fairly nice |

| c'. | ?? | Jan is aardig; | hij | is in ieder geval | nogal aardig. |

| Jan is nice | he | is in any case | fairly nice |

Other degree modifiers that may belong to this group are given in (68), although speakers may differ in their judgments regarding the results of the tests in (67). For example, at least some speakers can use the degree modifier betrekkelijkrelatively as a downtoner. Furthermore, the degree modifier tamelijkfairly can be used in at least some contexts as an amplifier with the meaning “quite”: dat is tamelijk beledigendthat is fairly/quite offensive. See also the discussion of aardig in the examples in (52) to (54).

| a. | betrekkelijk | tevreden | |

| relatively | satisfied |

| d. | redelijk | tevreden | |

| reasonably | satisfied |

| b. | nogal | aardig | |

| fairly | nice |

| e. | tamelijk | koud | |

| fairly | cold |

| c. | min of meer | bang | |

| less or more | afraid | ||

| 'more or less afraid' | |||

In (69) we see that neutral degree modifiers are similar to downtoners in that they cannot be modified and cannot occur in negative clauses. However, since the neutral degree modifier redelijkreasonably is clearly adjectival in nature, we cannot account for this in this case by appealing to its categorial status; cf. Jan is vrij redelijkJan is quite reasonable and Jan is niet redelijkJan is not reasonable.

| a. | * | Jan is nogal | redelijk | tevreden. |

| Jan is fairly | reasonably | satisfied |

| a'. | * | Jan is niet | redelijk | tevreden. |

| Jan is not | reasonably | satisfied |

| b. | * | Jan is redelijk | nogal | tevreden. |

| Jan is reasonably | fairly | satisfied |

| b'. | * | Jan is niet | nogal | tevreden. |

| Jan is not | fairly | satisfied |

This subsection discusses the interrogative degree modifier hoehow, which can be used in all contexts in which we find degree modifiers, i.e. as a modifier of a gradable set-denoting adjective or as a modifier of a degree modifier of a set-denoting adjective. We will discuss the two cases in separate subsections.

The interrogative degree modifier hoe can occur with all adjectives that can be modified by a degree modifier. Semantically, the degree modifier hoe can be characterized as a question operator, which leads to the semantic representation of (70a) in (70b). The answer to a question like (70a) will provide an amplifier (d > dn), a downtoner (d < dn), a neutral degree modifier (d ≈ dn), or some other element that can more precisely determine what position on the implied scale is intended, such as the deictic element zo, which will be discussed in Section 25.1.3, sub I.

| a. | Hoe goed is Jan? | |

| how good is Jan |

| b. | ?d [GOED (Jan,d)] |

In the case of attributive adjectives, the modified adjective must always follow the determiner een, as shown in (71); constructions of the English type how big a computer are not acceptable in Dutch.

| a. | [NP | Een | [AP hoe | grote] | computer] | heeft | hij | gekocht? | |

| [NP | a | how | big | computer | has | he | bought | ||

| 'How big a computer has he bought?' | |||||||||

| b. | * | Hoe groot | een computer | heeft | hij | gekocht? |

| how big | a computer | has | he | bought |

Interrogative hoehow can also be used as an interrogative modifier of adverbially used gradable adjectives like erg in erg ziekvery ill; cf. hoe erg ziekhow badly ill. Such adjective phrases are not normally found in prenominal attributive position; it is not a priori clear whether examples like (72a) are ungrammatical or it is not a priori clear whether examples like (72a) are ungrammatical or syntactically too complex to be easily handled. In view of what follows, it is useful to note that extracting the interrogative adverbial phrase from the nominal object makes things worse.

| a. | ?? | [NP | een [AP | [hoe erg] | zieke] | partner] | heeft hij? |

| ?? | [NP | a | how badly | ill | partner | has he | |

| Compare: 'How badly ill a partner does he have?' | |||||||

| b. | * | [Hoe erg]i | heeft | hij [NP | een [AP ti | zieke] | partner]]? |

| how badly | has | he | an | ill | partner |

The reason for paying attention to (72b) is that it is often possible to move interrogative adverbial degree phrases alone into the clause-initial position when the modified AP functions as a complementive, i.e. is used in the predicative position of the clause. This is shown in (73): wh-movement can strand the modified adjective and thus produce discontinuous APs. In fact, moving the whole AP usually produces a somewhat less felicitous result; judgments may vary from case to case and person to person. For more examples of this kind, see Corver (1990: §8.7).

| a. | [Hoe druk]i | is Jan [AP ti | bezig]? | |

| how busily | is Jan | engaged |

| a'. | ? | [AP Hoe druk bezig]i is Jan ti? |

| b. | [Hoe erg]i | is Jan [AP ti | ziek]? | |

| how badly | is Jan | ill |

| b'. | ? | [AP Hoe erg ziek]i is Jan ti? |

| c. | [Hoe hard]i | is die nieuwe computer [AP ti | nodig]? | |

| how badly | is that new computer | needed |

| c'. | ? | [AP Hoe hard nodig]i is die nieuwe computer ti? |

In (74) we see that the modifier hoe cannot be wh-moved by itself, but must pied-pipe the adjective it modifies: (74a) corresponds to (70a), where hoe directly modifies the adjective, and (74b) corresponds to (73a), where hoe modifies the amplifier of the adjective.

| a. | * | Hoei | is Jan [AP ti | goed]? |

| how | is Jan | good |

| b. | * | Hoei | is Jan [AP [ti | druk] | bezig]? |

| how | is Jan | busily | engaged |

The primeless examples in (75) show that extraction of the adjectival amplifier is also possible when it is preceded by the deictic element zo (cf. Section 25.1.3, sub IA), but in this case movement of the complete AP is also possible, as the primed examples of (75) show. The acceptability of the primed examples is important because it clearly shows that the adverbial phrase is part of the adjective phrase (the constituency test), as already suggested by the representations in (73).

| a. | [Zo druk]i | is Jan nou | ook | weer | niet [AP ti | bezig]. | |

| so busily | is Jan now | also | again | not | engaged | ||

| 'Jan is not that busy right now.' | |||||||

| a'. | [AP Zo druk bezig]i is Jan nou ook weer niet ti. |

| b. | [Zo erg]i | is Jan nou | ook | weer | niet [AP ti | ziek]. | |

| so badly | is Jan now | also | again | not | ill | ||

| 'Jan is not that ill.' | |||||||

| b'. | [AP Zo erg ziek]i is Jan nou ook weer niet ti. |

| c. | [Zo hard]i | is die nieuwe computer | nou | ook | weer | niet [AP ti | nodig]. | |

| so badly | is that new computer | now | also | again | not | needed | ||

| 'This new computer is not needed that badly.' | ||||||||

| c'. | [AP Zo hard nodig]i is die nieuwe computer nou ook weer niet ti. |

We see in (76) that the interrogative degree modifier can be extracted from an embedded clause and placed into the clause-initial position of the matrix clause, just as in the case of regular wh-movement.

| a. | [Hoe druk]i | denk | je | [dat | Jan [AP ti | bezig] | is]? | |

| how busily | think | you | that | Jan | engaged | is |

| b. | [Hoe erg]i | denk | je | [dat | Jan [AP | ziek ti] | is]? | |

| how badly | think | you | that | Jan | ill | is |

| c. | [Hoe hard]i | denk | je | [dat | die nieuwe computer [AP ti | nodig] | is]? | |

| how badly | think | you | that | a new computer | needed | is |

For completeness’ sake, the primeless cases in (77) show that it is also possible to extract the adjectival degree modifier from an embedded clause when it is modified by the deictic element zo. However, the primed examples show that extracting the complete adjective phrase yields a marked result; again, judgments may vary slightly from case to case and person to person.

| a. | [Zo druk]i | denk | ik | nou | ook | weer | niet | [dat | Jan [AP ti | bezig] | is]. | |

| so busily | think | I | now | also | again | not | that | Jan | engaged | is | ||

| 'It is not precisely the case that I think that Jan is that busy.' | ||||||||||||

| a'. | ? | [AP Zo druk bezig]i denk ik nou ook weer niet [dat Jan ti is]. |

| b. | [Zo erg]i | denk | ik | nou | ook | weer | niet | [dat | Jan [AP | ziek ti] | is]. | |

| so badly | think | I | now | also | again | not | that | Jan | ill | is | ||

| 'It is not precisely the case that I think that Jan is that ill.' | ||||||||||||

| b'. | ? | [AP Zo erg ziek]i denk ik nou ook weer niet [dat Jan ti is]. |

| c. | [Zo hard]i | denk | ik | nou ook weer niet | [dat | die nieuwe computer [AP ti | nodig] | is]. | |||||

| so badly | think | I | now also again not | that | that new computer | needed | is | ||||||

| 'It is not precisely the case that I think that that new computer is that essential.' | |||||||||||||

| c'. | ? | [Zo hard nodig]i denk ik nou ook weer niet [dat die nieuwe computer ti is]. |

The movement behavior of interrogative degree modifiers and degree modifiers modified by deictic zo is special, since the primeless examples in (78) show that in other cases splitting the AP leads to very bad results. Preposing the whole AP, as in the primed examples, is clearly preferred in these cases.

| a. | *? | Druki/(?)Erg druki | is Jan niet [AP ti | bezig]. |

| busily/very busily | is Jan not | engaged |

| a'. | (Erg) druk bezig is Jan niet. |

| b. | * | Ergi/*?Heel ergi | is Jan niet [AP ti | ziek]. |

| badly/very badly | is Jan not | ill |

| b'. | (Heel) erg ziek is Jan niet. |

| c. | *? | Hardi/(?)Heel hardi | hebben | we die nieuwe computer | niet | [AP ti nodig]. | |

| badly/very badly | have | we that new computer | not | [AP ti nodig]. | needed |

| c'. | (Heel) hard nodig hebben we die nieuwe computer niet. |

The examples in (79) show that degree modifiers can only be modified by interrogative hoe if they can also be modified by other degree modifiers; degree adverbs like zeervery and vrijrather in the (a)-examples in (79) are not gradable and resist modification by degree modifiers and interrogative hoe alike. Examples (79b&c) show that the same applies to non-gradable adverbially used adjectives like afgrijselijkatrociously and opmerkelijkstrikingly; cf. also the discussion of example (21) in Subsection IB.

| a. | * | Hoe/erg | zeer | ziek | is hij? |

| how/very | very | ill | is he |

| a'. | * | Hoe/erg | vrij | ziek | is hij? |

| how/very | rather | ill | is he |

| b. | * | Hoe/erg | afgrijselijk | lelijk | is dat gebouw? |

| how/very | atrociously | ugly | is that building |

| c. | * | Hoe/erg | opmerkelijk | mooi | is dat boek? |

| how/very | strikingly | beautiful | is that book |

Finally, the examples in (80) show that the morphologically amplified adjectives in (36) in Subsection IE also reject modification by both degree modifiers and interrogative hoe.

| a. | * | Hoe/erg | beeldschoon | is dat schilderij? |

| how/very | gorgeous | is that painting |

| b. | * | Hoe/erg | doodeng | is die film? |

| how/very | really.scary | is that movie |

| c. | * | Hoe/erg | oliedom | is die jongen? |

| how/very | extremely.stupid | is that boy |

| d. | * | Hoe/erg | beregoed | is dat optreden? |

| how/very | terrific | is that act |

We conclude this section on degree modification with a discussion of the exclamative marker wathow (lit.: what). As we saw in (60), the element wat can also be used as a downtoner, in which case it can be replaced by ietwat; we show this again in (81).

| a. | Jan is wat/ietwat | vreemd. | complementive | |

| Jan is somewhat | strange |

| b. | Jan is een | wat/ietwat | vreemde | jongen. | attributive | |

| Jan is a | slightly | strange | boy |

| c. | Jan loopt | wat/ietwat | vreemd. | adverbial | |

| Jan walks | somewhat | strange |

Example (82a) shows that preposing the adjectival complementive in (81a) into clause-initial position leads to a marginal result. Note that this sentence becomes perfectly acceptable when given an exclamative intonation contour, as in (82b), but this changes the meaning in a non-trivial way: wat no longer functions as a downtoner but as an amplifier, or alternatively, expresses emotional involvement or surprise on the part of the speaker. The downtoner wat and the exclamative marker wat differ in that the former cannot be accented, while the latter must be.

| a. | ?? | Wat vreemd | is Jan. | downtoner |

| somewhat strange | is Jan |

| b. | Wàt vréémd | is Jan! | exclamative | |

| what strange | is Jan | |||

| 'How strange Jan is!' | ||||

The following subsections will show that the use of exclamative wat is not restricted to complementive adjectives such as vreemdstrange in (82b), but is also possible with supplementive, attributive, or adverbial adjectives; cf. Section V11.3.4 for a more detailed discussion of the exclamative wat construction.

That exclamative wat should be considered an amplifier is supported by the examples in (83), which show that it blocks the use of other degree modifiers; we refer the reader to Section V11.3.4, sub I, for further discussion, and to example (114) below for possible counterexamples.

| a. | Wàt | (*zeer/*vrij) | vréémd | is die Jan | toch! | |

| what | very/rather | strange | is that Jan | prt | ||

| 'How strange Jan is!' | ||||||

| b. | Wàt | (*erg/*nogal) | áárdig | is jouw vader | toch! | |

| what | very/rather | nice | is your father | prt | ||

| 'How nice your father is!' | ||||||

The modified adjective cannot occur in the comparative/superlative form either, as shown in (84). This need not surprise us, since Section 26.3 will argue that comparative and superlative formation should be regarded as functionally similar to degree modification, and thus incompatible with the presence of other degree modifiers; cf. *zeer vreemder/het vreemdst (lit.: very stranger/the strangest).

| a. | * | Wàt | vréémder/het vreemdst | is die Jan | toch! |

| what | stranger/the strangest | is that Jan | prt |

| b. | * | Wàt | áárdiger/het aardigst | is jouw vader | toch! |

| what | nicer/the nicest | is your father | prt |

A notable property of exclamative wat is that it need not be adjacent to the adjective it modifies, but also allows the split pattern in (85). The primed examples show that in these cases the presence of an additional degree modifier is also blocked.

| a. | Wàt | is die Jan | toch | vréémd! | |

| what | is that Jan | prt | strange |

| a'. | * | Wàt | is die Jan | toch | zeer/vrij vréémd! |

| what | is that Jan | prt | very/quite strange |

| b. | Wàt | is jouw vader | toch | áárdig! | |

| what | is your father | prt | nice |

| b'. | * | Wàt | is jouw vader | toch | erg/nogal áárdig! |

| what | is your father | prt | very/quite nice |

The examples in (86) show that extraction of the exclamative element from its minimal clause is never possible, regardless of whether the modified adjective is stranded or pied-piped.

| a. | * | Wàt vréémdi | zei Marie | [dat | Jan ti | is]! |

| what strange | said Marie | that | Jan | is |

| a'. | * | Wàt zei Marie [dat Jan vréémd is]! |

| b. | * | Wàt áárdigi | zei | Jan [dat | jouw vader ti | toch is]! |

| what nice | said | Jan that | your father | is |

| b'. | * | Wàt zei Jan [dat jouw vader áárdig is]! |

The cases in (87) make it clear that exclamative wat cannot occur in the clause-initial position of an embedded clause either, again regardless of whether the modified adjective is stranded or pied-piped. In this respect, the exclamative phrase wat vreemd/aardighow strange/nice! differs from the interrogative phrase hoe vreemd/aardighow strange/nice?, which can easily replace the wat-phrases in the primeless examples in (86) and (87), even though the split pattern found in the primed examples is also categorically blocked for it; cf. Subsection IV for examples.

| a. | * | Marie vertelde | wàt vréémd | Jan | is. |

| Marie told | what strange | Jan | is |

| a'. | * | Marie vertelde wàt Jan vréémd is. |

| b. | * | Ik | vertelde | wàt áárdig | jouw vader | is. |

| I | told | what nice | your father | is |

| b'. | * | Ik | vertelde wàt jouw vader áárdig is. |

The examples in (88) show that the result is generally marginal when exclamative wat appears in a clause-internal position, although the result is impeccable when the exclamative phrase is preceded by the particle maar.

| a. | Jan is ??(maar) wàt vréémd! |

| b. | Jouw vader is ??(maar) wàt áárdig! |

| c. | Je gezicht is ??(maar) wàt róód! |

The examples above are all copular constructions, but exclamative wat can also be found in other complementive constructions; for yet unclear reasons, the vinden-construction in the (a)-examples seems to prefer the unsplit pattern (with maar), while the resultative construction in the (b)-examples prefers the split pattern.

| a. | ?? | Wàt | vind | ik | jouw vader | vréémd! |

| what | consider | I | your father | strange |

| a'. | Ik vind jouw vader maar wàt vréémd! |

| b. | Wàt | maak | je | die deur | víes, | zeg! | |

| what | make | you | that door | dirty | hey |

| b'. | ?? | Je maakt die deur maar wàt víes, zeg! |

The contrast between the examples with exclamative wat in (90) shows that the split pattern is also excluded in imperative constructions with perception verbs, such as kijkento look, but there are several reasons to consider this construction as special. First, the phrase containing the exclamative wat is placed in the initial position of a dependent clause, which is usually excluded; cf. example (87). The complement of the imperative kijklook is a true embedded clause, as proved by the fact that the finite copular verb is is placed in clause-final position. Second, the construction is special because hoehow can replace exclamative wat in (90a) without any significant change in meaning, i.e. the embedded clause with hoe is not interpreted as an embedded question. For completeness’ sake, note that the embedded clause in (90a) can also be reduced phonetically (by so-called sluicing): cf. Kijk (eens) wat/hoe mooi die tafel is!

| a. | Kijk (eens) [S | wàt/hoe | móói | die tafel | is]! | |

| look prt | what/how | beautiful | that table | is | ||

| 'Look how beautiful that table is!' | ||||||

| b. | * | Kijk (eens) [S wat die tafel mooi is]! |

Some examples with a supplementive are given in (91). In this case, the split pattern is strongly preferred over the unsplit pattern.

| a. | Wàt | liep | Jan bóós | weg! | |

| what | walked | Jan angry | away |

| a'. | ?? | Wàt bóós liep Jan weg! |

| b. | Wàt | ging | Jan tréurig | naar huis, | zeg! | |

| what | went | Jan sad | to home | hey |

| b'. | ?? | Wàt tréurig ging Jan naar huis, zeg! |

The fact that the split pattern is possible suggests that exclamative wat does not originate within the adjective phrase, but can be base-generated in the clause-initial position. The reason for this assumption is that extraction from supplementive adjective phrases is usually blocked; the examples in (92) show that while R-extraction is possible from the complementive in (92a), it is excluded from the supplementive in (92b).

| a. | Jan is [AP | boos | over de afwijzing]. | complementive | |

| Jan is | angry | about the rejection |

| a'. | Jan is daari [AP boos over ti ]. |

| b. | Jan liep [AP | boos | over de afwijzing] | weg. | supplementive | |

| Jan walked | angry | about the rejection | away |

| b'. | * | Jan liep daari [AP boos over ti ] weg. |

This suggests that supplementives are islands for extraction, so that it is unlikely that wat is extracted from the supplementives in (91a&b). We will see that this conclusion is supported by the data in Subsections C and D below.

A potential problem with the assumption that exclamative wat does not originate within the adjective phrase is that in clause-internal position wat must be adjacent to the adjective; this suggests that the two form a constituent. The examples in (93) show that, as in (88), the clause-internal placement of wat requires the presence of the particle maar.

| a. | Jan liep | *(maar) | wàt | bóós | weg! | |

| Jan walked | prt | what | angry | away |

| b. | Jan ging | *(maar) | wàt | tréurig | naar huis! | |