- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

The mental lexicon must somehow encode the form and meaning of lexical items as well as syntactic information. However, we have seen that there seem to be certain systematic relations between the relevant semantic and syntactic information; for example, agents are usually external arguments and therefore typically appear as the subject of an active clause. Given that we do not want to include predictable information like this in the lexicon, it is an important question as to whether more such correlations can be established. This section aims at linking the syntactic classification in Section 1.2.2, sub II, with the aspectual event classifications based on participant roles in Section 1.2.3, sub II.

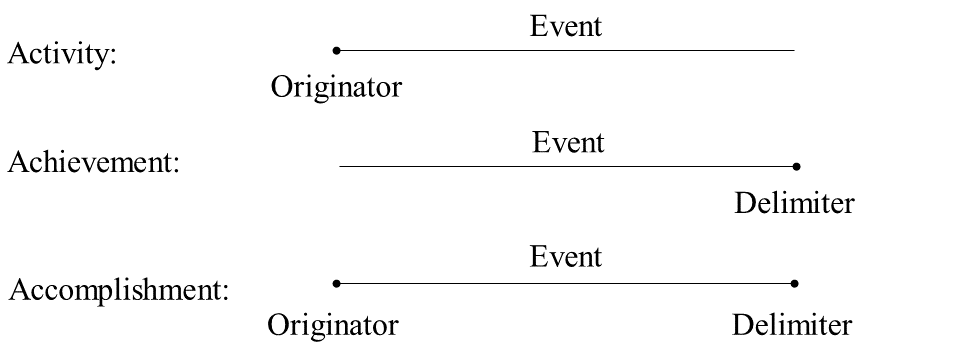

An advantage of aspectual event classifications based on participant roles, such as the one in (77), repeated here as (94), is that they are explicitly linked to syntactic verb classifications of the kind sketched in Section 1.2.2. Van Voorst (1988), for example, claims that originators and delimiters typically correspond to external agent/cause and internal theme arguments, respectively. Such linking is a priori desirable because form and meaning are usually seen as two sides of the same coin.

The requirement that the syntactic and semantic classifications should be linkable may also prevent these classifications from diverging too much, and can therefore be used to evaluate individual proposals. For instance, the examples in (95) suggest that the traditional distinction between monadic (intransitive) and dyadic (transitive) verbs is incompatible with the aspectual event classification in (94) because it fails to provide a natural account of the fact that lachento laugh denotes an activity, while overlijdento die denotes an achievement.

| a. | Jan lacht. | activity | |

| Jan laughs | |||

| 'Jan is laughing.' |

| b. | Jan verongelukte. | achievement | |

| Jan was.killed.in.an.accident |

The alternative syntactic classification developed in Section 1.2.2, sub II, fares better in this respect, since it distinguishes two types of monadic verbs. The contrast between the two examples in (95) follows from Van Voorst’s (1988) claim that external arguments of intransitive verbs such as lachento laugh typically function as originators, while internal theme arguments of unaccusative verbs such as overlijdento die typically function as delimiters. This clearly favors the alternative classification in Table 3 from Section 1.2.2, sub III, repeated here as Table 6, over the traditional one.

| name | external argument | internal argument(s) | |

| no internal argument | intransitive | nominative (agent) | — |

| impersonal | — | — | |

| one internal argument | transitive | nominative (agent) | accusative (theme) |

| unaccusative | — | nominative (theme) | |

| two internal arguments | ditransitive | nominative (agent) | dative (goal) accusative (theme) |

| nom-dat verb | — | dative (experiencer) nominative (theme) | |

| undative verb | — | nominative (goal) accusative (theme) |

Dyadic verbs can also denote states, activities, achievements or accomplishments. The traditional classification with an undifferentiated set of dyadic verbs provides no means to describe these differences, while according to the alternative classification in Table 6 at least the verb hebben differs from all other verbs in (96) in that it is an undative verb and thus has no agentive argument. If it turns out that undative verbs typically denote states, this can again be seen as an argument for the alternative classification.

| a. | De jongen | heeft | een kat. | state | |

| the boy | has | a cat |

| b. | De jongen | droeg | een kat. | activity | |

| the boy | carried | a cat |

| c. | De jongen | ontdekte | een kat. | achievement | |

| the boy | descried | a cat |

| d. | De jongen | verborg | een kat. | accomplishment | |

| the boy | hid | a cat |

Of course, it may be the case that the semantic and syntactic classifications do not reflect each other in all respects. For instance, the semantic distinctions between the examples in (96b-d) are not reflected by either the traditional or the alternative syntactic classification, and thus may be due to additional restrictions imposed by the verbs on their arguments in the way indicated in Table (97): although originators and delimiters may typically correspond to external agentive and internal theme arguments, respectively, it may be the case that external and internal arguments do not necessarily function as originators and delimiters; see also the linking rules in Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995: §4.1).

| external argument = originator | internal argument = delimiter | |

| dragen ‘to carry’ | + | — |

| ontdekken ‘to discover’ | — | + |

| verbergen ‘to hide’ | + | + |

The discussion of the examples in (96) suggests that the distinction between (96a) and (96b-d) is syntactic, whereas the distinctions between the examples in (96b-d) may be purely semantic. This may also explain the sharp contrast between the attributive (a)-examples in (98) and the remaining examples.

| a. | *? | de | een kat | hebbende | jongen |

| the | a cat | having | boy |

| a'. | * | de | gehadde | kat |

| the | had | cat |

| b. | de | een kat | dragende | jongen | |

| the | a cat | carrying | boy |

| b'. | de | gedragen | kat | |

| the | carried | cat |

| c. | de | een kat | ontdekkende | jongen | |

| the | a cat | descrying | boy |

| c'. | de | ontdekte | kat | |

| the | descried | cat |

| d. | de | een kat | verbergende | jongen | |

| the | a cat | hiding | boy |

| d'. | de | verborgen | kat | |

| the | hidden | cat |

Subsection I has shown that the traditional syntactic classification based on the adicity of verbs cannot be easily linked to the aspectual event classifications of the type in (94); the alternative proposal in Table 6, based both on the number of arguments and on the distinction between internal and external arguments, fares much better in this respect. This subsection will show that, on the assumption that (depending on the semantic properties of the verb) external arguments are optionally interpreted as originators and internal theme arguments are optionally interpreted as delimiters, it is indeed possible to relate the syntactic classification in Table 6 to the aspectual event classification in (94). Since goal arguments, but not experiencer arguments, can function as a “new location” of a theme, we will also briefly consider whether the second internal argument can be interpreted as a terminus (i.e. point of termination) in the sense of Tenny (1994); cf. the discussion of example (82) in Section 1.2.3, sub II.

In order to maximize contrasts and highlight a number of potential problems, we will group the verbs according to their adicity. We will not discuss impersonal verbs like regenento rain and vriezento freeze, as we have little to say about them in this context. Note also that the discussion below is occasionally somewhat tentative in nature; it presents an ongoing research program rather than a set of established facts/insights. The discussion below will make clear that there are still a number of questions requiring further investigation.

At first glance, the case of monadic verbs seems rather simple: as predicted, verbs with the behavior of prototypical intransitive verbs such as lachento laugh denote activities, while verbs with the behavior of prototypical unaccusative verbs such as arriverento arrive denote achievements.

| a. | Jan heeft/*is | gelachen. | |

| Jan has/is | laughed |

| a'. | Jan is/*heeft | gearriveerd. | |

| Jan is/has | arrived |

| b. | * | de | gelachen | jongen |

| the | laughed | boy |

| b'. | de | gearriveerde | jongen | |

| the | arrived | boy |

| c. | Er | werd | gelachen. | |

| there | was | laughed |

| c'. | * | Er | werd | gearriveerd. |

| here | was | arrived |

However, there are a number of monadic verbs that exhibit mixed behavior and seem to refer to states: this is illustrated for the verbs bloedento bleed and drijvento float in (100). The selection of the auxiliary hebben and the impossibility of using the past participle attributively suggest that we are dealing with intransitive verbs, while the impossibility of impersonal passivization suggests that we are dealing with unaccusative verbs.

| a. | Jan heeft/*is | gebloed. | |

| Jan has/is | bled |

| a'. | Jan heeft/*is | op het water | gedreven. | |

| Jan has/is | on the water | floated |

| b. | * | de | gebloede | jongen |

| the | bled | boy |

| b'. | * | de | gedreven | jongen |

| the | floated | boy |

| c. | * | Er | werd | gebloed. |

| there | was | bled |

| c'. | * | Er | werd | gedreven. |

| there | was | floated |

That we are not dealing with an activity is clear from the fact that the subject can be inanimate, while the subjects of verbs denoting an activity usually take animate subjects or a small set of inanimate subjects, such as computer, which can be construed as performing the activity. That we are not dealing with an achievement is clear from the fact that there is no logically implied endpoint.

| a. | Jan/de wond | bloedt | heftig. | |

| Jan/the wound | bleeds | fiercely |

| b. | Jan/de band | drijft | op het water. | |

| Jan/the tire | floats | on the water |

Since we have adopted as our working hypothesis that external and internal arguments function only optionally as originators and delimiters, respectively, there is no a priori reason to exclude an unaccusative status of these verbs. If drijven and bloeden were unaccusative, this would imply that selection of the auxiliary zijnto be and attributive use of the past participle are sufficient but not necessary conditions for assuming unaccusativity; Subsection B2 will show that there is indeed good reason to assume that auxiliary selection and attributive use of past participles not only depend on the unaccusativity of the verb, but are subject to additional aspectual conditions; cf. Mulder (1992) and Levin & Rappaport Hovav (1995) for similar conclusions.

Table 6 distinguishes three types of dyadic verbs: transitive, nom-dat and undative verbs. These three groups will be discussed in the following subsections.

The examples in (97b-d), repeated here as (102), have already shown that prototypical transitive verbs can denote activities, achievements, and accomplishments. This was the original motivation for our claim that external and internal arguments assume the roles of originator and delimiter, respectively; cf. Table (97) in Subsection I.

| a. | De jongen | droeg | een kat. | activity | |

| the boy | carried | a cat |

| b. | De jongen | ontdekte | een kat. | achievement | |

| the boy | descried | a cat |

| c. | De jongen | verborg | een kat. | accomplishment | |

| the boy | hid | a cat |

Nom-dat verbs are characterized by the fact that their subject can follow the object, which appears as a dative noun phrase in German. Since this also holds for passivized ditransitive verbs, Den Besten (1985) concluded that the subjects of nom-dat verbs are internal theme arguments; cf. Sections 1.2.2, sub IIB, and 2.1.3 for details.

| a. | dat | die meisjesnom | Peter/hemdat | direct | opvielen. | |

| that | those girls | Peter/him | immediately | prt.-struck | ||

| 'that Peter/he noticed those girls immediately.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Peter/hemdat | die meisjesnom | direct | opvielen. | |

| that | Peter/him | those girls | immediately | prt.-struck |

This analysis immediately accounts for the fact that examples such as (103) are interpreted as achievements: nom-dat verbs are like monadic unaccusative verbs in that they lack an external argument that could function as an originator and that their internal argument can function as a delimiter. The Nom-dat verbs discussed so far also have all the typical properties of monadic unaccusative verbs: they select the auxiliary zijn, their past participles can be used attributively to modify a head noun that corresponds to the subject of the clause, and they resist passivization.

| a. | dat | die meisjes | Peter/hem | direct | zijn/*hebben | opgevallen. | |

| that | those girls | Peter/him | immediately | are/have | prt.-struck |

| b. | de | hem | direct | opgevallen | meisjes | |

| the | him | immediately | prt.-struck | girls |

| c. | * | Er | werd | Peter/hem | direct | opgevallen. |

| there | was | Peter/him | immediately | prt.-struck |

However, the claim that internal arguments function only optionally as delimiters predicts that there are also nom-dat verbs without an implied endpoint, thus denoting simple states. Den Besten (1985) lists a number of nom-dat verbs with this property, including the verb smakento taste in (105).

| a. | dat | de broodjes | Peter/hem | smaakten. | |

| that | the buns | Peter/him | tasted | ||

| 'that Peter/he enjoyed his buns.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Peter/hem | de broodjes | smaakten. | |

| that | Peter/him | the buns | tasted |

Although the relative order of the object and subject in (105b) clearly shows that the subject de broodjes is an internal argument, it should be noted that verbs such as smaken do not exhibit all the properties we find in (104). Like all unaccusative verbs, they do not allow impersonal passivization, but they select the auxiliary hebben instead of zijn and their past participles cannot be used attributively to modify a head noun corresponding to the subject of the clause.

| a. | dat | Peter/hem | de broodjes | hebben/*zijn | gesmaakt. | |

| that | Peter/him | the buns | have/are | tasted |

| b. | * | de Peter/hem | gesmaakte | broodjes |

| the Peter/him | tasted | buns |

| c. | * | Er | werd | Peter/hem | gesmaakt. |

| there | was | Peter/him | tasted |

In all relevant respects, the pattern in (106) is similar to the pattern established for the stative verbs drijvento float and bloedento bleed in (100). This supports the proposal in Subsection A that these verbs are also unaccusative verbs and that their mixed behavior with respect to the unaccusativity tests should be explained by assuming that auxiliary selection and attributive use of past participles are subject to both syntactic and aspectual conditions.

Undative verbs do not have an external argument and so we expect that there is no originator; undative verbs therefore denote either states or achievements, depending on whether or not their internal theme argument functions as a delimiter. The examples in (107) show that this prediction is borne out: depending on the verb in question, we are dealing with a state, an achievement, or a special kind of state expressing retention.

| a. | Jan heeft | het boek. | state | |

| Jan has | the book |

| b. | Jan krijgt | het boek. | achievement | |

| Jan gets | the book |

| c. | Jan houdt | het boek. | retention | |

| Jan keeps | the book |

The achievement reading in (107b) may be due to the fact that the recipient-subject Jan functions as a goal, which in turn triggers a delimiter interpretation of the internal theme argument; if so, this would support our proposal in the introduction to this section that goals function as a terminus (point of termination) in the event.

The claim that goals function as end points may also explain why the recipient-subjects of cognition verbs like wetento know and kennento know in (108), which we will show in Section 2.1.4 to belong to a second set of undative verbs, must be interpreted as experiencers. The reason is that these verbs denote states and are thus incompatible with an interpretation of the recipient-subject as terminus (i.e. goal).

| JanExp | kent | de fijne kneepjes van het vak. | state | ||

| Jan | knows | the detailed tricks of the trade | |||

| 'Jan knows the tricks of the trade.' | |||||

Now compare the triadic accomplishment verb lerento teach in (109a) with its non-causative dyadic counterpart lerento learn in (109b). Since the indirect object of the triadic verb and the recipient-subject of the dyadic verb both act as a goal, which introduces a point of termination into the event structure, the achievement reading of (109b) is accounted for.

| a. | Marie leert | JanGoal | de fijne kneepjes van het vak. | accomplishment | |

| Marie teaches | Jan | the tricks of the trade |

| b. | JanGoal | leert | de fijne kneepjes van het vak. | achievement | |

| Jan | learns | the detailed tricks of the trade |

Given the discussion of the examples in (108) and (109), it might be tempting to analyze other ditransitive verbs with experiencer subjects, like the perception verbs horento hear and ziento see, also as undative verbs; we will leave it to future research to investigate whether this might be on the right track.

Indirect objects of ditransitive verbs are usually goals. If goal arguments introduce termini, we expect (definite) direct objects to function normally as delimiters; this in turn correctly predicts that, depending on whether the subject functions as an originator or not, ditransitive verbs usually denote achievements or accomplishments, as shown in (110).

| a. | Zijn succes | gaf | Peter een prettig gevoel. | achievement | |

| his success | gave | Peter a nice feeling |

| b. | Jan | stuurde | Peter | een mooi boek. | accomplishment | |

| Jan | sent | Peter | a nice book |

It seems that the semantic classification in (94) and the syntactic classification in Table 6 can be linked to a certain extent. At the moment, we can only show this for the more prototypical cases; future research will have to show whether this is also possible for less prototypical cases. We expect that such research will reveal certain potential problems for some of the claims in the discussion above. For example, the unaccusative verbs overlijdento die, arriverento arrive and vertrekkento leave in (111) seem to differ in the extent to which the subject is able to control the event. While the subject of overlijden has virtually no control, the subject of vertrekken does have control over the event; the subject of arriveren seems to take an intermediate position in this respect.

| a. | Jan overlijdt | morgen. | |

| Jan dies | tomorrow |

| b. | Jan vertrekt/arriveert | morgen. | |

| Jan leaves/arrives | tomorrow |

The contrast could be accounted for either by assuming that the internal argument of an unaccusative verb can function not only as a delimiter but also as an originator, or by assuming that the assignment of the property of control is not linguistic in nature, but reflects our knowledge of the world. Since the former would open up many new classification possibilities, we should only adopt such an approach if further investigation shows that the newly predicted verb classes actually exist.