- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section concludes the overview of the syntactic classification of adpositions by discussing the structural relationship between the four main classes that have been distinguished. Since this is still relatively uncharted territory, much of what follows is speculative and should be taken only as a first indication of what the structure of adpositional phrases might look like. Some studies dedicated to this issue, like Van Riemsdijk (1978/1990), Koopman (2010) and Den Dikken (2003b), suggest that the correct analysis may in fact be more intricate than suggested here; cf. Broekhuis & Den Dikken (2018) for an illustration.

We begin by discussing the relationship between prepositions and postpositions. One way to describe the difference between the two is to say that prepositions take their nominal complement to the right, while take their complement to the left. Since we have seen that the postpositions are a proper subset of the prepositions, this can be formalized by assuming the lexical entries in (154): (154a) expresses that adpositions that can be used as prepositions only take their complement to the right, whereas adpositions that can be used either as prepositions or as postpositions can take their complement either to the right or to the left.

| a. | preposition: __ NP |

| b. | postposition: __ NP or NP __ |

A problem for the proposal in (154) is that the prepositional and postpositional phrases differ in meaning: the former typically denote a (change of) location, whereas the latter denote a direction. In German, this difference is not expressed by word order but by case marking: both locational and directional adpositions are prepositional, but locational adpositions assign dative case, whereas directional adpositions assign accusative case. Since German and Dutch are so closely related, this casts serious doubt on the lexical entry in (154b). It may be that in Dutch, too, directional adpositions take their complement to the right, but because Dutch has no morphological case, the nominal complement must be moved to the left of the adposition in order to signal directional meaning. This leads to the movement analysis in (155b).

| a. | preposition: __ NP | |

| b. | postposition: __ NP |

| a'. | prepositional phrase: [P NP] | |

| b'. | postpositional phrase: NPi [P ti] |

The analysis in (155) might be supported by the fact that the complement of a preposition cannot be scrambled or topicalized, whereas the complement of a postposition can. This would be surprising if they both occupied the complement position of the adposition but would follow naturally if we assume that the base-position of the noun phrase in (155a') is not accessible to these movement operations, whereas the derived position in (155b') is. The relevant data are given in (156).

| a. | Jan zat daarnet | in de boom. | |||||

| Jan sat just.now | in the tree | ||||||

| 'Jan sat in the tree just now.' | |||||||

| b. | Jan klom | daarnet | de boom | in. | |||

| Jan climbed | just.now | the tree | into | ||||

| 'Jan climbed into the tree just now.' | |||||||

| a'. | * | Jan zat de boom daarnet in. |

| b'. | Jan klom de boom daarnet in. |

| a''. | * | De boom zat Jan daarnet in. |

| b''. | De boom klom Jan daarnet in. |

If the movement analysis of postpositional phrases in (155b') is tenable, a similar analysis may be feasible for circumpositional phrases. Instead of assuming that circumpositions are discontinuous heads, as is done in traditional grammar, one can assume that circumpositional phrases actually consist of an adposition that takes a PP as its complement, which (for some reason) must be moved leftwards; cf. Zwart (1993:365ff.) and Claessen & Zwarts (2010).

| a. | circumposition: __ PP |

| b. | circumpositional phrase: PPi [P ti] |

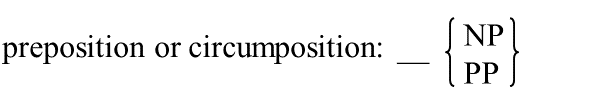

The analysis in (157) has several potential advantages. First, it can account for the fact that the PP-part in (157) must have a form that can be used independently as a prepositional phrase. Second, the analysis in (157) leaves open the possibility that not all prepositions can occur as the second member (= the P-part in (157b)) of circumpositional phrases, and that there are certain elements that can occur as the second member of a circumpositional phrase but cannot be used as a preposition. This would follow if we assume that, as in the case of verbs, complementation of adpositions is lexically constrained; adpositions like voor, which can only occur as prepositions, have the categorial frame in (158a), adpositions like heen or vandaan, which can only occur as the second member of a circumposition, have the categorial frame in (158b), and adpositions like aan, which can be used both as a preposition and as the second member of a circumposition, have the categorial frame in (158c).

| a. | preposition: __ NP |

| b. | circumposition: __ PP |

| c. |  |

Third, the movement analysis in (157b) predicts that circumpositional phrases can be split; just like the nominal complement of a postposition, the prepositional complement can be moved further leftwards. This can happen when the prepositional phrase contains a nominal wh-phrase, as in (159), which is taken from Section 32.2.5. Note that this analysis does not shed any new light on the question of why the topicalization of the PP in (157b) generally leads to a marked result.

| Achter welke optocht | liepen | de kinderen | aan? | ||

| behind which parade | walked | the children | aan | ||

| 'After which parade did the children run?' | |||||

Finally, the analysis in (157b) can account for the fact that toe occurs both as the second member of circumpositional phrases and as the counterpart of tot in pronominalized PPs like er ... toe in example (160b). It suffices to say that circumpositional phrases and pronominal PPs are both derived by leftward movement of their complements, and that the use of toe (instead of tot) is a morphological reflex of these movements.

| a. | dat | Jan Marie steeds | tot diefstal | verleidt. | |

| that | Jan Marie all.the.time | to theft | tempts | ||

| 'that Jan is tempting Marie to steal all the time.' | |||||

| b. | dat Jan Marie er | steeds | toe | verleidt. | |

| that Jan Marie there | all.the.time | to | tempts | ||

| 'that Jan is tempting Marie to it all the time.' | |||||

A potential problem with the analysis that circumpositions are the result of leftward PP-movement is that movement is often assumed to cause freezing, i.e. the moved phrase becomes an island for extraction; cf. Koster (1978a: §2.6.4.4), Corver (2006b/2017) and Ruys (2008). The data on R-extraction from circumpositional phrases seem to contradict this: the analysis in (157) implies that the PP bij de koffie in (161a) occupies its base position, yet R-extraction is excluded; the PP over het hek in (161b), on the other hand, is said to have moved leftward, yet R-extraction is possible from circumpositional phrases like over het hek heen; cf. Section 32.2.5 for a more detailed discussion of R-extraction.

| a. | Die koekjes | zijn | voor bij de koffie. | |

| Jan bought | biscuits | for with the coffee | ||

| 'Those biscuits are intended to be eaten with the coffee.' | ||||

| a'. | * | Die koekjes zijn daar voor bij. |

| b. | Jan sprong | over het hek | heen. | |

| Jan jumped | over the fence | heen |

| b'. | Jan sprong er over heen. |

However, it has been argued that Dutch clauses also have an underlying head-complement order; cf. Zwart (2011: §9) for an excellent review. If this is indeed true, then the preverbal position of a PP-complement is also a derived position, so that also in this case, freezing is also to be expected. However, the examples in (162) show that R-extraction is possible from the preverbal position; it is instead R-extraction from postverbal PPs that is impossible.

| a. | dat | Jan | wacht op de post. | |

| that | Jan | waits for the post |

| a'. | * | dat | Jan er | wacht | op. |

| that | Jan there | waits | for |

| b. | dat | Jan | op de post wacht. | |

| that | Jan | for the post waits |

| b'. | dat | Jan er | op | wacht. | |

| that | Jan there | for | waits |

This means that on the assumption that Dutch has an underlying head-complement order, the freezing effect cannot be assumed to occur with all types of movement: PP-movement resulting in the PP-V order or the surface order of circumpositional phrases must be assumed not to evoke freezing, but to have the opposite effect of facilitating movement. In any case, the (a) and (b)-patterns in (163) must receive a similar analysis assuming an underlying head-complement order. We leave this for further research.

| a. | * | daari ... V [PP P ti] | cf. (162a') |

| a'. | daari ... [PP P ti]j V tj | cf. (162b') |

| b. | * | daari ... P [PP P ti] | cf. (161a') |

| b'. | daari ... [PP P ti]j P tj | cf. (161b') |

We conclude with a brief remark on the relation between intransitive adpositions and particles. We have seen that the former probably function as heads of regular adpositional phrases, and that they are special only in that they do not take a complement, or can leave their complement implicit. This is not true of particles. One difference between particles and all other classes of adpositions is that particles are incapable of assigning case; their arguments are typically assigned accusative case by the verb or nominative case in the subject position of the clause, just like the logical subjects of other predicatively used adpositional phrases. There are two analyses that seem to be compatible with this observation. According to the first analysis, particles are just like intransitive adpositions in that they do not take a complement, which then of course begs the question as to why they behave differently from intransitive adpositions. According to the second analysis, particles are like unaccusative verbs in that they do take a complement but cannot assign case to it; therefore, the complement must be moved into a position where it can be assigned nominative or accusative case. Arguments for the second approach can be found in Den Dikken (1995a).