- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Subsection I will first recapitulate some of the differences between prepositions and postpositions from Section 32.1.2, sub II. Subsection II then provides a semantic classification of the postpositions and discusses properties of the different subclasses.

Spatial postpositions are always directional: they indicate that the located object follows a path related to the reference object. In this respect, postpositional phrases differ from prepositional phrases, which usually only refer to a (change of) location (with the exception of PPs headed by the directional prepositions in Table 16). This difference accounts for the fact that prepositional phrases can be used as complements of both location verbs like liggento lie and motion verbs like springento jump, whereas postpositional phrases cannot be used as complements of location verbs.

| a. | Jan ligt/springt | in | het zwembad. | |

| Jan lies/jumps | in(to) | the swimming.pool |

| b. | Jan springt/*ligt | het zwembad | in. | |

| Jan jumps/lies | the swimming.pool | into |

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the change-of-location reading of prepositional phrases and the directional reading of postpositional phrases: the two examples in (254) with the motion verb springento jump seem almost synonymous. However, the examples in (255) show that only the postpositional phrase expresses the notion of a path.

| a. | Jan is op de trap | gesprongen | (#naar zijn kamer). | |

| Jan is on the stairs | jumped | to his room | ||

| 'Jan has jumped onto the stairs (to his room).' | ||||

| b. | Jan is de trap | op | gesprongen/gerend | (naar zijn kamer). | |

| Jan is the stairs | onto | jumped/run | to his room | ||

| 'Jan has jumped/run up the stairs (to his room).' | |||||

The locational construction in (255a) expresses that Jan has been involved in a jumping event, as a result of which he has reached a certain position on the stairs. The construction in (255b), on the other hand, does not imply that Jan is on the stairs after completing the activity; this may or may not be the case. This can be made clear by adding an adverbial phrase such as naar zijn kamerto his room, which refers to the endpoint of the path Jan has traversed; with this adverbial phrase added, the perfect tense example in (255b) suggests that Jan is in his room. Adding this adverbial phrase to (255a), on the other hand, yields an unacceptable result. The number sign in (255a) indicates that the naar-PP can marginally be interpreted as an attributive modifier of the noun trap.

Another difference is that locational prepositional phrases cannot occur as complements of verbs of traversing (i.e. verbs that denote movement along a certain path) like rijdento drive, fietsento cycle, etc. To see this, we have to consider perfect-tense constructions, because a verb like rijden is ambiguous between a normal activity verb, in which case it takes the auxiliary hebben, and a verb of traversing, in which case it takes the auxiliary zijn. So, in (256a) we are dealing with the activity verb rijden; what is expressed is that the eventuality of driving takes place on the mountain. In (256b), on the other hand, we are dealing with a verb of traversing; what is expressed is that Jan is moving along a path up the mountain.

| a. | Jan heeft/*?is | op de berg | gereden. | |

| Jan has | on the mountain | ridden | ||

| 'Jan has ridden on the mountain.' | ||||

| b. | Jan is/*heeft | de berg | op | gereden. | |

| Jan has | the mountain | onto | ridden | ||

| 'Jan has ridden up the mountain.' | |||||

Related to this, note that example (257a) does not imply anything about Jan’s position after the activity is finished: it may be the case that he ends his activity in the same place where he started it. However, this is impossible in the case of (257b): Jan must have traversed the path up the mountain, so that his final position on the mountain is a higher than his initial position.

| a. | Jan heeft | drie kilometer | op de berg | gereden. | |

| Jan has | three kilometers | on the mountain | ridden | ||

| 'Jan has ridden three kilometers on the mountain.' | |||||

| b. | Jan is | drie kilometer | de berg | op | gereden. | |

| Jan has | three kilometers | the mountain | up | ridden | ||

| 'Jan has ridden three kilometers up the mountain.' | ||||||

Returning for a moment to the examples in (255), we can conclude from the grammaticality of both (255a) and (255b) that the unaccusative verb springen can be used both as a motion verb and as a verb of traversing. Note also that the intransitive version of springen, i.e. the version with the auxiliary hebben, acts like an activity verb: Jan heeft op de trap gesprongenJan jumped on the stairs simply expresses that the activity of jumping takes place on the stairs.

Having recapitulated the main semantic differences between prepositional and postpositional phrases, we can now turn to the meaning of the individual spatial postpositions in Table 7, repeated here as Table 18 in a different form for convenience. The conclusion of the following discussion will be that, in general, there is only one group of postpositions, which corresponds to the inherent prepositions in Table 17: the deictic and absolute prepositions in this table have no postpositional counterparts.

| postposition | example | translation |

| af | het veld af rennen | to run from the field |

| binnen | het huis binnen gaan | to go into the house |

| door | het hek door lopen | to walk through the gate |

| in | het huis in gaan | to go into the house |

| langs | de beek langs wandelen | to walk along the brook |

| om | de hoek om gaan | to turn the corner |

| op | het veld op rennen | to run onto the field |

| over | het grasveld over rennen | to run across the lawn |

| rond | ?het meer rond wandelen | to walk around the lake |

| uit | de auto uit stappen | to step out of the car |

| voorbij | het huis voorbij rijden | to drive past the house |

If we compare the list of postpositions in Table 18 with the classification of spatial prepositions in Table 17, we see that there is no deictic preposition with a postpositional counterpart. This is remarkable in view of the fact that most postpositions correspond to inherent prepositions; this is because the deictic prepositions can also be used inherently.

Very few of the absolute prepositions in Table 17 have a postpositional counterpart. For the inherently directional (i.e. type II) absolute ones, such as naarto, this is not surprising because they already denote a path. The only directional preposition in this group with a postpositional counterpart is voorbijpast, but this is not surprising either, since this preposition can sometimes also be used as a locational preposition; cf. the discussion of example (205) in Section 32.3.1.2, sub IIB.

| a. | Goirle ligt | even | voorbij | Tilburg. | locational reading | |

| Goirle lies | just | past | Tilburg |

| b. | Jan reed | Tilburg | voorbij. | directional reading | |

| Jan drove | Tilburg | past |

Of the non-directional (i.e. type I) absolute prepositions, only omaround and rondaround can be used as postpositions. The use of om is very restricted. In fact, it can only be used in the more or less fixed combinations in (259a&b); examples such as (259c) are unacceptable.

| a. | Jan ging | de hoek | om. | |

| Jan went | the corner | around | ||

| 'Jan turned the corner.' | ||||

| b. | Jan ging | een blokje | om. | |

| Jan went | a blokje | around | ||

| 'Jan went for a walk.' | ||||

| c. | * | Jan liep | de tafel | om. |

| Jan walked | the table | around |

The postposition rond is a bit more common. In addition to more or less fixed combinations like (260a), it also appears in (slightly marked) examples like (260b).

| a. | Jan reisde | de wereld | rond. | |

| Jan traveled | the world | round |

| b. | (?) | Jan wandelde | de stad | rond. |

| Jan walked | the city | round |

The limited use of the postpositions om/rond may be due to the fact, discussed in Section 32.3.1.2, sub II, that their prepositional counterparts can sometimes at least marginally be used directionally; cf. the discussion of (201c). That they have this ability is also supported by the fact that a prepositional phrase can be used in constructions such as (261), where the PP denotes the extent of the road; as we saw in examples (216) and (220) in Section 32.3.1.2, sub IIB, the extent reading typically involves directional PPs.

| De weg | loopt | rond/om de stad. | ||

| the road | walks | around the city | ||

| 'The road runs round the city.' | ||||

The vast majority of productively used postpositions correspond to inherent prepositions. Three groups can be distinguished.

The first group of postpositions is characterized by the fact that the interior of the reference object is part of the implied path. The postpositional phrases headed by in and binnen in (262a) express that the reference object is the endpoint of the path; however, the starting point is exterior to the reference object. The examples in (262b&c) show that in can but binnen cannot be used when the postpositional phrase has an extent reading or functions as a modifier of a noun phrase.

| a. | Jan liep | de stad | in/binnen. | |

| Jan walked | the town | into | ||

| 'Jan walked into the town.' | ||||

| b. | de weg | loopt | de stad | in/*binnen | |

| the road | walks | the town | into | ||

| 'the road leads into town' | |||||

| c. | de weg | de stad | in/*binnen | |

| the road | the town | into | ||

| 'the road into the town' | ||||

The postpositional phrase headed by uit in (263) expresses that the reference object is the starting point of the path, but the endpoint is outside it. Note that binnen in (262a) can be used as a postposition in predicatively used postpositional phrases, while its antonym buiten in (263a) cannot.

| a. | Jan liep | de stad | uit/*buiten. | |

| Jan walked | the town | out.of | ||

| 'Jan walked out of the town.' | ||||

| b. | de weg | loopt | de stad | uit | |

| the road | walked | the town | out.of | ||

| 'the road leads out of town' | |||||

| c. | de weg | de stad | uit | |

| the road | the town | out.of | ||

| 'the road out of the town' | ||||

Finally, the postpositional phrase headed by door in (264) expresses that the reference object is a subpart of the path: both the starting point and the endpoint of the path are exterior to it. Recall that the preposition door can also be used in directional constructions; cf. the discussion of (243) and (244) in Section 32.3.1.2, sub III, for the difference between the two directional uses of door.

| a. | Jan liep | de tunnel | door. | |

| Jan walked | the tunnel | through | ||

| 'Jan walked through the tunnel.' | ||||

| b. | de weg | de tunnel | door | |

| the road | the tunnel | through | ||

| 'the road through the tunnel' | ||||

The claim that in and binnen take the interior of the reference object as the endpoint of the implied path is supported by the fact that (262a) entails that Jan is in town after the completion of the event; the symbol ⊫ indicates that the intended entailment is valid. The claim that uit denotes a path with an endpoint exterior to the reference object is supported by the fact that we can infer from (263a) that Jan is out of town after the completion of the event. Note in passing that we cannot substitute uit for buiten in (265b'), which indicates that there is no longer any contact between the located and the reference object after the completion of the event; cf. the discussion of example (236).

| a. | Jan liep de stad in/binnen. | |

| 'Jan walked into the town.' |

| a'. | ⊫ | Jan bevindt | zich | in de stad. | |

| ⊫ | Jan is.situated | refl | in the town | ||

| 'Jan finds himself in town.' | |||||

| b. | Jan liep | de stad uit. | |

| Jan walked | the town out | ||

| 'Jan walked out of the town.' | |||

| b'. | ⊫ | Jan bevindt | zich | buiten de stad. | |

| ⊫ | Jan is.situated | refl | outside the town | ||

| 'Jan is outside (not in) the town.' | |||||

The postpositions in and binnen in (262a) seem to be more or less equivalent. However, they differ in that the latter requires the located object to end up in a position within the reference object, whereas the former does not. This is clear from the fact that binnen cannot be used in (266a): the implication is that some part of the nail has not entered the wall. Example (266b) shows that the postposition uitout of does not require the located object to be (completely) removed from the reference object. This shows that in this respect the postpositions behave similarly to the corresponding prepositions; cf. the discussion of Figure 23 and Figure 25 in Section 32.3.1.2, sub IIIB.

| a. | Jan sloeg | de spijker | (slechts) | één cm | de muur | in/*binnen. | |

| Jan hit | the nail | only | one cm | the wall | into | ||

| 'Jan hammered the nail (only) one cm into the wall.' | |||||||

| b. | Jan trok | de spijker | (slechts) | één cm | de muur | uit/*buiten. | |

| Jan drew | the nail | only | one cm | the wall | out.of | ||

| 'Jan pulled the nail (only) one cm out of the wall.' | |||||||

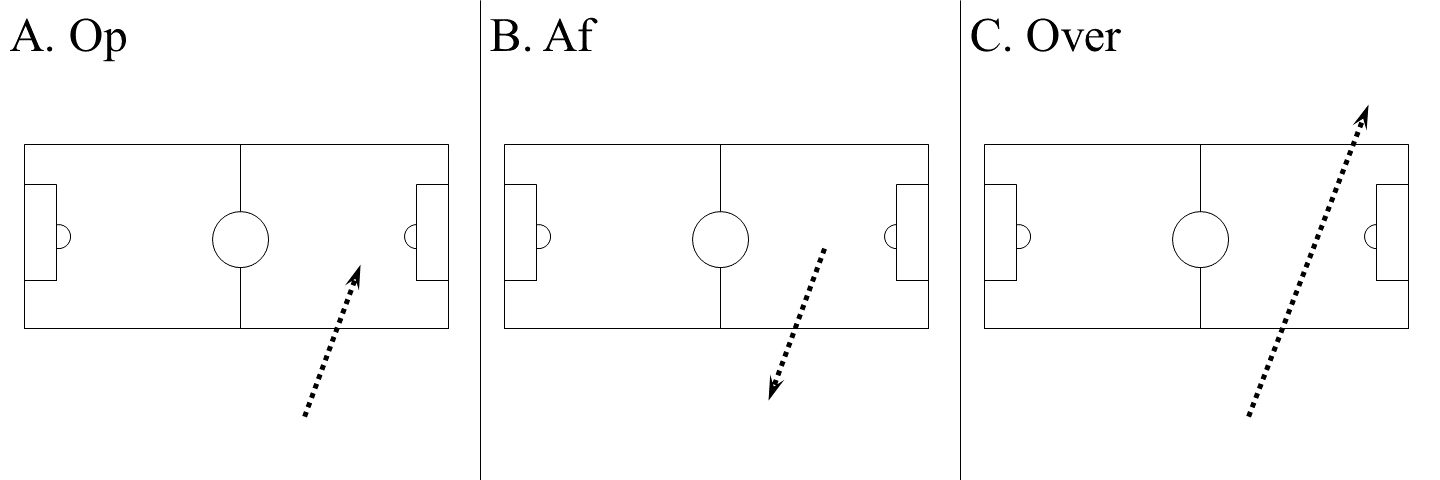

The second group of postpositions is characterized by the fact that the path runs along the surface of the reference object. The postposition oponto indicates that the endpoint but not the starting point of the path is situated on the reference object, while affrom indicates that the starting point but not the endpoint of the path is situated on the reference object. In the case of over neither the starting point nor the endpoint of the path is situated on the reference object, but some part of the path is. The respective paths of the postpositional phrases in (257) are shown in Figure 30.

| a. | De supporter | rende | het veld | op. | |

| the supporter | ran | the field | onto | ||

| 'The supporter ran onto the field.' | |||||

| b. | De supporter | rende | het veld | af. | |

| the supporter | ran | the field | from | ||

| 'The supporter ran off the field.' | |||||

| c. | De supporter | rende | het veld | over. | |

| the supporter | ran | the field | across | ||

| 'The supporter ran across the field.' | |||||

The claim that op implies that the endpoint of the implied path is situated on the surface of the reference object is supported by the fact that we can infer from (267a) that the fan is on the field after completion of the event. The claim that af denotes a path with an endpoint exterior to the reference object is supported by the fact that we can infer from (262b) that the fan is not on the field after completion of the event.

| a. | De supporter rende het veld op. | |

| 'The supporter ran onto the field.' |

| a'. | ⊫ | De supporter | bevindt | zich | op het veld. | |

| ⊫ | the supporter | is.situated | refl. | on the field | ||

| 'The supporter is on the field.' | ||||||

| b. | De supporter rende | het veld | af. | |

| 'The supporter ran off the field.' | ||||

| b'. | ⊫ | De supporter | bevindt | zich | buiten het veld. | |

| ⊫ | the supporter | is.situated | refl | outside the field | ||

| 'The supporter is off the field.' | ||||||

The exact interpretation of these postpositions also depends on the properties of the reference object: whereas in the case of a field the correct English translation of op and af would be “onto” and “off”, the correct renderings would be “up” and “down” when we are dealing with e.g. a hill. Although the intuitions are not as clear as in the case of the examples in (268), the core semantics of Figure 30 also seems to be present in (269): example (269a) is preferably interpreted as meaning that only the endpoint of the implied path is situated on the mountain; example (269b) is preferably interpreted as meaning that only the starting point is situated on the mountain (although this implication is not as strong as in the case of the circumpositional phrase van de berg af).

| a. | Jan | reed | de berg | op. | |

| Jan | drove | the mountain | onto | ||

| 'Jan drove up the mountain.' | |||||

| b. | Jan reed | de berg | af. | |

| Jan drove | the mountain | from | ||

| 'Jan drove down the mountain.' | ||||

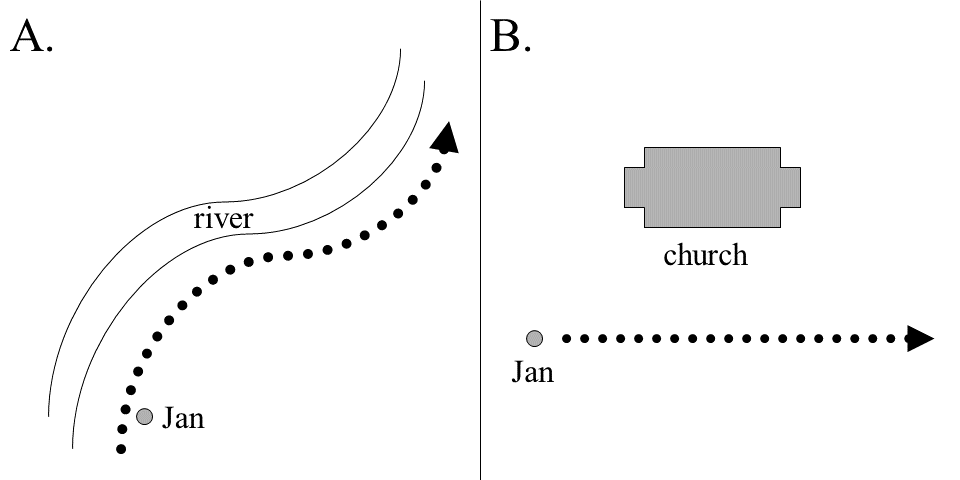

The third group has only one member, the adposition langsalong, and it implies that the path is more or less parallel to the length dimension of the reference object. In this respect, the preposition and the postposition langs in (270) behave in a similar way, as can be seen by comparing of Figure 31A below with Figure 20 in Section 32.3.1.2, sub III.

| a. | Jan wandelt | vaak | langs de rivier. | preposition | |

| Jan walks | often | along the river |

| b. | Jan wandelt | vaak | de rivier langs. | postposition | |

| Jan walks | often | the river along |

The difference between the preposition and the postposition langs is often not very clear, which may be due to the fact that the prepositional phrase in (270a) can also be used directionally. First, the examples in (271) show that the verb wandelento walk can take either the auxiliary hebben or zijn in the perfect tense. As with other spatial PPs, we expect the PP in (271a) to be locational (the activity of walking takes place along the river), whereas (271b) has a change-of-location reading. In the latter reading, the implication should be that Jan is located along the river as a result of the walking event, but this reading is not prominent, to say the least. The more prominent reading of (271b) is directional in nature; Jan has followed a path along the river. Note that this directional reading is found in example (271b'), where the langs-PP functions as an (optional) adverbial phrase characterizing the course of the path, and the predicative naar-PP refers to the endpoint of the path.

| a. | Jan heeft | langs de rivier | gewandeld. | |

| Jan has | along the river | walked |

| b. | Jan is | langs de rivier | gewandeld. | |

| Jan is | along the river | walked |

| b'. | Jan is | (langs de rivier) | naar Breda | gewandeld. | |

| Jan is | along the river | to Breda | walked |

Second, the prepositional phrase can also be used in sentences like (272a-b), where the langs-PP denotes the extent of the road: as we saw in examples (216) and (220) in Section 32.3.1.2, sub IIB, the extent reading typically involves directional PPs.

| a. | De weg | loopt | langs de rivier. | |

| the road | walks | along the river | ||

| 'The road runs along the river.' | ||||

| b. | de weg | langs de rivier | |

| the road | along the river |

The above discussion shows that the preposition langs can sometimes also be used directionally. The difference between directional prepositional and postpositional langs can be related to the dimensional properties of the reference object. If the reference object is very long, as in (270) and (271), the path denoted by langs can be either smaller or larger than the length of the reference object; if the reference object is relatively short, as in (273), the default interpretation seems to be that the path is longer than the length of the object (see Figure 31B). The marked status of (273b) suggests that langs is more likely to appear as a preposition in the latter case.

| a. | Jan | fietst | elke dag | langs de kerk. | |

| Jan | cycles | every day | along the church | ||

| 'Jan cycles everyday past the church.' | |||||

| b. | *? | Jan | fietst | elke dag | de kerk | langs. |

| Jan | cycles | every day | the church | along |

In the examples up to this point, the paths extend along the horizontal dimension of the reference objects. Example (274) shows that the path can also extend in the vertical dimension.

| dat Jan | langs het touw/de muur | geklommen | is. | ||

| that Jan | along the rope/the wall | climbed | is | ||

| 'that Jan has climbed along the rope/wall.' | |||||

Superficially seen, it looks as if that the direction of the vertical path can be further specified by the elements omhoog/omlaagupwards/downwards, as in (275a). However, this is not the correct analysis. The fact, illustrated in (275b), that the PP langs het touw/de muur is optional and can undergo PP-over-V shows that we are dealing with a particle verb, omhoog/omlaag klimmento climb up/down, modified by an adverbial locational PP headed by langs.

| a. | dat Jan | langs het touw/de muur | omhoog/omlaag | geklommen | is. | |

| that Jan | along the rope/the wall | upwards/downwards | climbed | is | ||

| 'that Jan has climbed upwards/downwards along the rope/wall.' | ||||||

| b. | dat Jan | omhoog/omlaag | geklommen | is | (langs het touw/de muur). | |

| that Jan | upwards/downwards | climbed | is | along the rope/the wall |

This shows that example (275a) must be analyzed along the lines of example (271b') above, which also involves an adverbial locational PP headed by langs. That this is indeed the case is also clear from the fact that in (276) the particle omhoog/omlaag can easily be replaced by the unsuspected predicative PP naar boven.

| a. | dat Jan | (langs het touw/de muur) | naar boven | geklommen | is. | |

| that Jan | along the rope/the wall | upwards | climbed | is | ||

| 'that Jan has climbed upwards along the rope/wall.' | ||||||

| b. | dat Jan | naar boven | geklommen | is | langs het touw/de muur. | |

| that Jan | upwards | climbed | is | along the rope/the wall |