- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

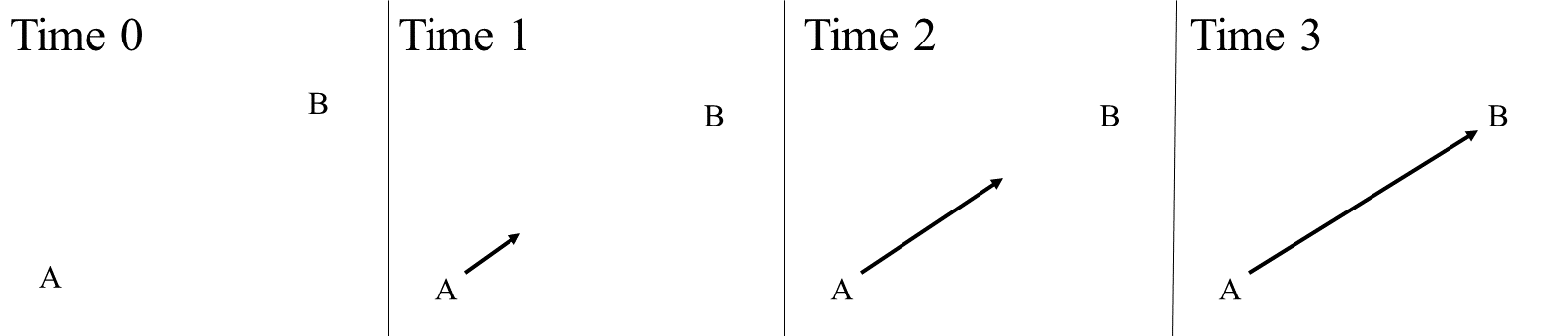

Directional PPs express that the located object is traversing a particular path. A path can be defined as an ordered set of vectors, each of which is associated with a specific position on the timeline. The path denoted by van A naar Bfrom A to B can now be represented as in Figure 7, taken from Section 32.3.1.1, sub V, which can be read as a cartoon.

The following subsections discuss some possible cases of modification of directional PPs. It will be shown that the modification possibilities are restricted to those modifiers which express to what extent the implied path has been covered.

The fact that the directional PPs also involve vectors triggers the expectation that they behave like locational PPs, to the extent that they can also be modified by adverbial phrases of orientation and distance. However, this does not seem to be borne out. Consider the examples in (61).

| a. | # | Jan liep | recht/schuin | naar de barkruk. |

| Jan walked | straight/diagonally | to the bar stool |

| b. | * | Jan liep | ver/vlak/pal | naar de barkruk. |

| Jan walked | far/close | to the bar stool |

The examples in (61a) are acceptable, but not in the intended reading in which rechtstraight and schuindiagonally modify the path that Jan is traversing; they are acceptable only if recht and schuin are interpreted as supplementives predicated of Jan, expressing something about Jan’s posture. This shows that recht and schuin are comparable to elements like rechtopupright, which can never be used as a modifier of a PP. Example (61b) is clearly not acceptable.

A possible modifier of orientation could be the PP via een omwegvia a detour, which is in a paradigm with the adjective rechtstreeksdirectly. However, the fact illustrated in (62) that examples with these modifiers can be paraphrased by means of the clausal conjunct ... en doet dat + AP/PP... and does that AP/PP indicates that the modifiers function as VP adverbials; cf. adverbial tests.

| a. | Jan rijdt | rechtstreeks/via een omweg | naar Groningen. | |

| Jan drives | directly/via a detour | to Groningen |

| b. | Jan rijdt | naar Groningen | en | hij doet dat | rechtstreeks/via een omweg. | |

| Jan drives | to Groningen | and | he does that | directly/via a detour |

The elements midden, achter, voor, boven and onder, discussed in Section 34.1.3, also do not work well with a directional adpositional phrase; the examples in (63) are all unacceptable in the intended reading, where the located object is situated with respect to the reference object. The number sign indicates that (63b) is acceptable if boven is interpreted as “upstairs”; this reading, in which boven functions as an adverbial phrase referring to the place where the eventuality of throwing the picture into the cupboard took place, is irrelevant here.

| a. | Jan sprong | (*midden) | de plas | in. | |

| Jan jumped | middle | the puddle | into | ||

| 'Jan jumped into the puddle.' | |||||

| b. | Jan gooide | de foto | (#boven/*onder) | de kast | in. | |

| Jan threw | the picture | above/under | the closet | into | ||

| 'Jan threw the picture into the closet.' | ||||||

| c. | Jan sprong | (*achter/*voor) | de auto | op. | |

| Jan jumped | behind/in.front.of | the car | onto | ||

| 'Jan jumped onto the car.' | |||||

The judgments on the examples in (63) are quite revealing, given that their change-of-location counterparts in (64), in which the adpositional phrase has the form not of a postpositional but of a prepositional phrase, are perfectly acceptable.

| a. | Jan sprong | (midden) | in de plas. | |

| Jan jumped | middle | the puddle | ||

| 'Jan jumped into the middle of the puddle.' | ||||

| b. | Jan gooide | de foto | (boven/onder) | in de kast. | |

| Jan threw | the picture | above/under | the closet | ||

| 'Jan threw the picture on the top/bottom shelf of the closet.' | |||||

| c. | Jan sprong | (*achter/*voor) | de auto | op. | |

| Jan jumped | behind/in.front.of | the car | onto | ||

| 'Jan jumped on the front/rear of the car.' | |||||

The discussion of the examples in this subsection strongly suggests that modifiers of orientation and distance cannot be used in directional PPs. Consequently, we have not been able to construct convincing cases for such forms of modification.

Modification of directional adpositional phrases seems to be possible for those modifiers that express the extent to which the implied path is covered. There are two types of modifiers of this kind: nominal measure phrases and adjectives like helemaalcompletely and gedeeltelijkpartly.

Some clear cases of modification of directional adpositional phrases can be seen in (65). Note that the reference objects (i.e. the internal arguments of the postpositions in and op) can either precede or follow the modifier. However, since reference objects can also precede VP adverbials such as snelquickly, as in Jan wandelde snel het bos inJan quickly walked quickly into the woods and Jan wandelde de berg snel opJan quickly climbed the mountain, it seems plausible that the order in which the reference object precedes the modifier of the directional PP is derived by leftward movement of the noun phrase.

| a. | Jan wandelde | <het bos> | 3 km <het bos> | in. | |

| Jan walked | the forest | 3 km | into | ||

| 'Jan walked three kilometers into the woods.' | |||||

| b. | Jan wandelde | <de berg> | 3 km <de berg> | op. | |

| Jan walked | the mountain | 3 km | onto | ||

| 'Jan walked three kilometers up the mountain.' | |||||

In (66), we see similar examples with an adjectival modifier; the choice of the modifier depends on the nature of the reference object.

| a. | Jan wandelde | <het bos> | diep <het bos> | in. | |

| Jan walked | the forest | deep | into | ||

| 'Jan walked deep into the woods.' | |||||

| b. | Jan klom | hoog | de boom | in. | |

| Jan climbed | high | the tree | into | ||

| 'Jan climbed high up into the tree.' | |||||

The modifications in (65) and (66) do not relate to the orientation or the magnitude of the vectors involved, but to the implied path: what is expressed is that a subpart of the path has been traversed. For example, the examples in (65) presuppose an itinerary that goes into the woods/up the mountain, and it is claimed that the located object has traversed 3 kilometers of this path. The difference between the directional constructions in (65) and the non-directional constructions in (67) is that in the latter Jan may have returned to his starting position after he has finished walking 3 kilometers, while in the former Jan must be located in the woods/up the mountain.

| a. | Jan wandelde | 3 km in het bos. | |

| Jan walked | 3 km in the forest | ||

| 'Jan walked three kilometers in the woods.' | |||

| b. | Jan wandelde | 3 km op de berg. | |

| Jan walked | 3 km on the mountain | ||

| 'Jan walked three kilometers on the mountain.' | |||

The adjectives in the non-directional constructions in (68) differ from the directional ones in (66) in that they only specify the place where the eventuality takes place: (68a) expresses that the activity of walking took place deep in the forest, and (68b) that the activity of climbing took place high in the tree.

| a. | Jan wandelde | diep | in het bos. | |

| Jan walked | deep | in the forest | ||

| 'Jan was walking in the depth of the woods.' | ||||

| b. | Jan klom | hoog | in de boom. | |

| Jan climbed | high | in the tree | ||

| 'Jan was climbing high in the tree.' | ||||

Modifications of the type in (65) and (66) are only possible if the path is not intrinsically bounded, i.e. if the beginning and end of the path are not fixed. In (65a), this condition is satisfied; even though the path must be at least partly located in the forest, it is left implicit where it starts and ends, i.e. any position outside the forest is a suitable starting point and any position inside the forest is a suitable endpoint of the implied path. Something similar holds for the path referred to by the postpositional phrase in (65b). That the boundedness of the paths is relevant is also shown by the contrast between the use of directional PPs headed by the prepositions vanfrom, naarto and totuntil in (69a) and the use of the directional PPs headed by the phrasal preposition in de richting vantowards in (69b). The intuition is that the length of the path in (69a) is determined by some implied anchoring point, e.g. the position of the speaker. This means that the length of the implied path is contextually fixed, and therefore cannot be modified. In (69b), on the other hand, the beginning and the end of the implied path are not specified (either explicitly or implicitly), so that the length of the implied path is not contextually determined and modification is possible.

| a. | * | Jan reed | twee kilometer | van/naar/tot Groningen. |

| Jan drove | two kilometer | from/to/until Groningen |

| b. | Jan reed | twee kilometer | in de richting van Groningen. | |

| Jan drove | two kilometers | towards Groningen |

Other cases of directional phrases that denote paths that are inherently bounded and therefore cannot be modified are given in (70). For example, in (70a-c) the length of the implied paths is largely determined by the dimensions of the reference object; the beginning and end of the implied paths are bounded by two positions adjacent to and on opposite sides of the field/tunnel/house. Note that it is not clear whether the degraded example in (70d) can be accounted for in a similar way.

| a. | * | Jan liep | twintig meter | het veld | over. |

| Jan walked | twenty meters | the field | across |

| b. | * | Jan liep | twee kilometer | de tunnel | door. |

| Jan walked | two kilometers | the tunnel | through |

| c. | ?? | Jan liep | twee meter | het huis | voorbij. |

| Jan walked | two meter | the house | past |

| d. | ?? | Jan liep | drie kilometer | het kanaal | langs. |

| Jan walked | three kilometers | the canal | along |

Finally, note that both the nominal and the adjectival modifiers can be extracted from the adpositional phrase by wh-movement. This is demonstrated in (71) by the interrogative counterparts of the examples in (65) and (66).

| a. | Hoeveel kilometer | wandelde | Jan het bos | in? | |

| how.many kilometers | walked | Jan the forest | into |

| a'. | Hoeveel kilometer | wandelde | Jan de berg | op? | |

| how.many kilometers | walked | Jan the mountain | onto |

| b. | Hoe diep | wandelde | Jan het bos | in? | |

| how deep | walked | Jan the forest | into |

| b'. | Hoe hoog | klom | Jan de boom | in? | |

| how high | climbed | Jan the tree | into |

The boundedness of the implied path is also relevant in the case of modification by helemaal/gedeeltelijkcompletely/partly, which indicates whether the implied path is completely or partly covered. If the path is not inherently bounded, as in (72a), the use of these modifiers makes no sense and therefore results in unacceptability. Given the discussion of (65b) in the previous subsection, the grammaticality of (72b) may come as a surprise, but the difference in acceptability between (65b) and (72b) goes hand in hand with a difference in interpretation: in (65b) the endpoint of the implied path is left implicit in the sense that it can be situated anywhere on the mountain, whereas in (72b) the endpoint must be the top of the mountain. In other words, in (65b) op is interpreted as “onto”, whereas in (72b) it is interpreted as “on top of”. If the “on top of” reading is not possible, as in (72b'), the judgments are as expected. Note in passing that (72b) differs from (65b) in that the modifier must follow the reference object (under neutral intonation of the sentence).

| a. | * | Jan wandelde | <het bos> | helemaal/gedeeltelijk <het bos> | in. |

| Jan walked | the forest | completely/partly | into |

| b. | Jan wandelde | <de berg> | helemaal/gedeeltelijk <*de berg> | op. | |

| Jan walked | the mountain | completely/partly | onto |

| b'. | * | De supporter | rende | <het veld> | helemaal/gedeeltelijk <het veld> | op. |

| the fan | ran | the field | completely/partly | onto |

The pattern in (73) is more or less what we expect to find: the PPs in (73a) denote bounded paths and modification by helemaal is correctly predicted to be possible, although it is surprising that the use of gedeeltelijk gives rise to a somewhat marked result; the PPs in (73b) denote unbounded paths, and modification by helemaal/gedeeltelijk is correctly predicted to be impossible.

| a. | Jan reed | helemaal/?gedeeltelijk | van/naar/tot Groningen. | |

| Jan drove | completely/partly | from/to/until Groningen |

| b. | * | Jan reed | helemaal/gedeeltelijk | in de richting van Groningen. |

| Jan drove | completely/partly | towards Groningen |

The examples in (74) all involve inherently bounded paths, and the use of helemaal/gedeeltelijk is possible, as predicted. Note that in these cases, the modifier also follows the reference object (under neutral intonation of the sentence).

| a. | Jan liep | <het veld> | helemaal/gedeeltelijk <*het veld> | over. | |

| Jan walked | the field | completely/partly | across |

| b. | Jan liep | <de tunnel> | helemaal/gedeeltelijk <*de tunnel> | door. | |

| Jan walked | the tunnel | completely/partly | through |

| c. | Jan liep | <het huis> | helemaal/gedeeltelijk <*het huis> | voorbij. | |

| Jan walked | the house | completely/partly | past |

| d. | Jan liep | <het kanaal> | helemaal/gedeeltelijk <*het kanaal> | langs. | |

| Jan walked | the canal | completely/partly | along |

The modification possibilities in (72) and (74) correlate nicely with the distribution of the adjective heelwhole as an attributive modifier or predeterminer of the noun phrase expressing the reference object, as in (75). However, there seems to be a subtle difference in meaning between the two sets of constructions: whereas the examples in (72) and (74) suggest that the path proceeds in a more or less straight line, the examples in (75) suggest that the path proceeds in a more disordered (e.g. crisscross) manner. This might also explain the contrast between (75c&d) and (75e&f); while it is certainly possible to go crisscross across a field/through a tunnel, it seems less easy to pass a house/follow a canal in this way.

| a. | * | Jan liep | <heel> | het | <hele> | bos | in. |

| Jan walked | whole | the | whole | forest | into |

| b. | Jan liep | <*heel> | de | <?hele> | berg | op. | |

| Jan walked | whole | the | whole | mountain | onto |

| c. | Jan liep | <heel> | het | <hele> | veld | over. | |

| Jan walked | whole | the | whole | field | across |

| d. | Jan liep | <heel> | de | <hele> | tunnel | door. | |

| Jan walked | whole | the | whole | tunnel | through |

| e. | ? | Jan liep | <heel> | het | <hele> | huis | voorbij. |

| Jan walked | whole | the | whole | house | past |

| f. | ? | Jan liep | <heel> | het | <hele> | kanaal | langs. |

| Jan walked | whole | the | whole | canal | along |

The intuition that the implied paths in (75) are of a more disordered nature may be related to the fact that heelwhole forces a distributive reading if used as an attributive modifier of the head of a reference object in a locational construction. Consider the examples in (76).

| a. | Er | wonen | mensen | in het | kasteel. |

| a'. | Er | wonen | mensen | in het hele | kasteel. | |

| there | live | people | in the whole | castle | ||

| 'The (whole) castle is inhabited by people.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | liggen | palen | langs de | weg. |

| b'. | Er | liggen | palen | langs de hele | weg. | |

| there | lie | poles | along the whole | road | ||

| 'Poles are lying (all) along the road.' | ||||||

While (76a) is compatible with one family living in the castle (or with only a part of the castle being inhabited), example (76a') implies that the castle is divided into separate living units; people are more or less evenly distributed throughout the castle. Similarly, (76b) could be used to express that there is a pile of poles lying by the side of the road, while (76b') implies that the poles are placed at specific intervals along the road. Similarly, the examples in (75) could express that the implied path is more or less “evenly distributed” on the reference object; cf. Section N20.2 for a more detailed discussion of the predeterminer/attributive modifier heel.

Most of the examples in the previous subsections involve postpositional phrases. Since circumpositional phrases can also be used directionally, they have the same modification possibilities as the postpositional phrases. If the denoted path is not inherently bounded, as in (77a), the circumpositional phrase can be modified by a nominal measure phrase. If the path is bounded, as in (77b), the modifiers helemaal and gedeeltelijk can be used.

| a. | Jan zwom | drie kilometer | tegen | de stroom | in. | |

| Jan swam | three kilometers | against | the current | in |

| b. | Jan rende | gedeeltelijk/helemaal | naar | Groningen | toe. | |

| Jan ran | partly/completely | to | Groningen | toe |

At first glance, the type of modification in (65a&b) appears to be of a similar nature to what we saw in the examples with locational PPs in (53). This impression becomes even stronger when we consider the directional counterparts of the latter examples given in (78).

| a. | Jan sloeg | de spijker | 3 cm | de muur | in. | |

| Jan hit | the nail | 3 cm | the wall | into | ||

| 'Jan hammered the nail 3 cm into the wall.' | ||||||

| a'. | Jan sloeg | de spijker | recht/schuin | de muur | in. | |

| Jan hit | the nail | straight/diagonally | the wall | into | ||

| 'Jan hammered the nail straight/diagonally into the wall.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan trok | de spijker | 3 cm | de muur | uit. | |

| Jan pulled | the nail | 3 cm | the wall | out.of | ||

| 'Jan pulled the nail 3 cm out of the wall.' | ||||||

| b'. | Jan trok | de spijker recht/schuin | de muur | uit. | |

| Jan pulled | the nail straight/diagonally | the wall | out.of | ||

| 'Jan pulled the nail straight/diagonally out of the wall.' | |||||

As in the case of the prepositional phrases headed by in/uit, the nominal measure phrases of the postpositional phrases in the primeless examples of (78) indicate the extent to which the located object penetrates/protrudes from the wall; cf. Figure 6A&B. Similarly, the modifiers recht and schuin in the primed examples indicate in what way the nail penetrates/protrudes from the wall; cf. the discussion of Figure 6A'&B'. So, if we are dealing with modification involving distance and orientation, the adpositional phrases headed by in and uit must denote inwardly oriented vectors.

However, this conclusion is questionable. First, consider the examples in (79). Subsection IIB has shown that the modifiers in (79a) do seem to specify the part of the path denoted by the directional adpositional phrase covered by Jan. This is also clear from the fact that they cannot be used in the construction in (79b), in which the PP acts as a locational (adverbial) phrase.

| a. | Jan wandelde | de berg | gedeeltelijk/helemaal/voor de helft | op. | |

| Jan walked | the mountain | partly/entirely/halfway | onto | ||

| 'Jan walked partly/completely/halfway to the top of the mountain.' | |||||

| b. | * | Jan wandelde | gedeeltelijk/helemaal/voor de helft | op de berg. |

| Jan walked | partly/entirely/halfway | on the mountain |

In (80), on the other hand, the modifiers do not require the presence of a directional phrase; if we replace the directional postpositional phrase in (80a) by a locational prepositional phrase, as in (80b), the result is still perfectly acceptable. This is because we are not dealing with modification of the path, but with modification of the located object; the modifier indicates the part of the located object that has penetrated the reference object. In short, we are not dealing with modification of the adpositional phrase but with modification of the located object.

| a. | Jan sloeg | de spijker | gedeeltelijk/helemaal/voor de helft | de muur | in. | |

| Jan hit | the nail | partly/entirely/halfway | the wall | into |

| b. | Jan sloeg | de spijker | gedeeltelijk/helemaal/voor de helft | in de muur. | |

| Jan hit | the nail | partly/entirely/halfway | into the wall |

A weaker argument against assuming that (80a) involves modification of the implied path is that the modifier helemaal in this example does not alternate with the adjective heelwhole in example (81): heel is used here as a predeterminer or an attributive modifier of the noun phrase referring to the reference object. Example (75) has shown that this is usually possible when we are dealing with modification of a path.

| * | Jan sloeg | de spijker | <heel> | de | <hele> | muur | in. | |

| Jan hit | the nail | whole | the | whole | wall | into |