- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Since Jackendoff (1972), two main classes of adverbial phrases are usually distinguished. The first class is the set of VP adverbials (also called predicate adverbials), which function semantically as modifiers restricting the denotation of the predicate expressed by the verb phrase: prototypical examples are manner adverbs such as hardloudly in (1a). The second class is the set of clause adverbials, also known as sentence adverbials, which can perform a variety of other functions: prototypical examples are modal adverbials such as waarschijnlijkprobably and the negation nietnot in (1b), which can be seen as logical operators taking scope over a proposition. The logical formulas in the primed examples are added to illustrate this semantic difference.

| a. | Jan lacht | hard. | |||

| Jan laughs | loudly | ||||

| 'Jan is laughing loudly.' | |||||

| b. | Jan komt | waarschijnlijk/niet. | |||

| Jan comes | probably/not | ||||

| 'Jan will probably come/Jan will not come.' | |||||

| a'. | hard lachen(j) |

| b'. | ◊komen(j)/¬komen(j) |

This section provides a general discussion of the distinction between VP and clause adverbials and proposes a number of tests that can be used to distinguish the two types.

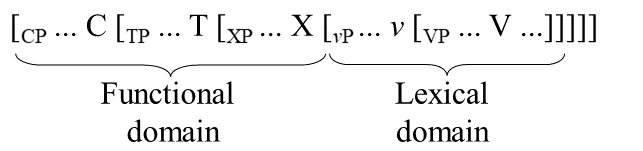

The introduction to this section above has shown that VP adverbials modify the predicative part of the clause, whereas clause adverbials minimally modify the propositional part of the clause. Moreover, the labels VP adverbial and clause adverbial correctly suggest that the two types of adverbials apply to different syntactic domains, which we will assume to correspond to the so-called lexical and functional domain of the clause. We will briefly introduce these theoretical concepts in this subsection (cf. Chapter 9 for a more detailed discussion); the takeaway message from this discussion is that clause adverbials usually occur more to the left in the clause (i.e. higher in the clause structure) than VP adverbials.

The lexical domain of the clause consists of the main verb and its arguments and (optional) VP modifiers, which together form a proposition. For example, the verb kopento buy in (2a) takes a direct object as its internal argument and is then modified by the manner adverb snelquickly, while the resulting complex predicate is finally predicated of the verb’s external argument Jan. The complex phrase thus formed expresses the proposition represented by the logical formula in (2b).

| a. | [Jan | [snel | [het boek | kopen]]] | |

| Jan | quickly | the book | buy |

| b. | buy quickly (Jan, the book) |

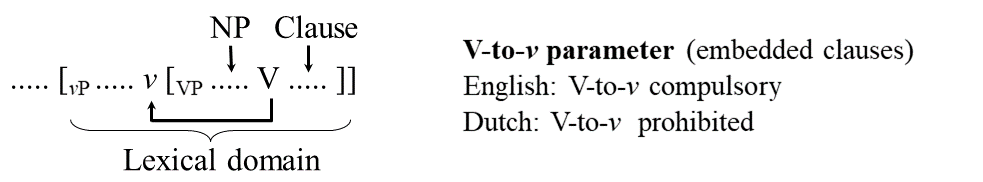

Since it is unlikely that the linking of semantic and syntactic structure varies arbitrarily across languages, it is often assumed that the hierarchical structure of the lexical domain is more or less invariant across languages, and that surface differences in word order between languages are superficial phenomena, e.g. due to differences in linearization or movement. Adopting a movement approach, we can assume that the lexical domain is hierarchically structured as in (3), where NP and Clause point to the positions normally occupied by the nominal/clausal internal theme argument of the verb. This means that we can now account for the difference in word order between VO languages such as English and OV languages such as Dutch by assuming that the former, but not the latter, has obligatory V-to-v movement; cf. Section 9.4, sub IC, for a more detailed discussion.

|

The structure in (2a) can now be made more explicit as in (4): internal arguments such as the theme het boekthe book are generated within VP, VP adverbials such as the manner adverb snelquickly are adjoined to VP, and external arguments such as the agent Jan are generated as the specifier of the light verb v (where the term light is used to indicate that it has little or no meaning). For concreteness’ sake, we have assumed that the manner adverb is adjoined to the maximal projection VP within the lexical domain; we will return to this assumption shortly.

| [vP | Jan v [VP | snel [VP | het boek | kopen]]] | ||

| [vP | Jan | quickly | the book | buy |

Clause adverbials are generated external to the lexical domain, i.e. within the functional domain, which contains various functional heads that add information to the proposition expressed by the lexical domain (i.e. vP). For example, the functional head T(ense) in (5) adds the tense feature [±past] to the proposition. Similarly, the feature of the functional head C(omplementizer) determines the illocutionary force (declarative, interrogative, etc.), as can be seen from the fact that the complementizers datthat and ofif/whether introduce embedded declarative and interrogative clauses, respectively. In addition to these functional heads, there may be other functional heads, indicated by X in (5), which introduce other features.

|

Modal adverbs and negation seem to be located at the boundary between the functional and the lexical domain. Assuming that adverbial phrases are introduced into the structure by adjunction to the various maximal projections found in representation (5), we should conclude that they are adjoined to vP (or one of its adjacent functional projections XP). This is illustrated in (6b), in which we have followed the general assumption that the subject is moved from its vP-internal position into the regular subject position external to vP. For completeness’ sake, note that the adjunction analysis is not uncontroversial; for example, Cinque (1999) has made a very strong case for assuming that the various subtypes of clause adverbials are generated as specifiers of designated functional heads. If we accept such an approach, the adverb waarschijnlijk would be located in the specifier position of a functional head EM expressing epistemic modality, as indicated in (6b').

| a. | dat | Jan waarschijnlijk | het boek | koopt. | |

| that | Jan probably | the book | buys | ||

| 'that Jan will probably buy the book.' | |||||

| b. | dat Jani [vP waarschijnlijk [vP ti v [VP het boek koopt]]]. |

| b'. | dat Jani [EMP waarschijnlijk EM [vP ti v [VP het boek koopt]]]. |

Because the choice between the two analyses will not be crucial for the discussion of the Dutch data in this chapter, we refer the reader to Cinque (1999/2003), Ernst (2002), and the references cited there for detailed discussions of the pros and cons of the two approaches. We also refer the reader to Section 13.3.1 on Neg-movement, where we will show that there are strong empirical reasons for adopting Cinque’s analysis, at least for the negative adverb nietnot.

The hypothesis that clause adverbials are external while VP adverbials are internal to the lexical domain of the clause correctly predicts that the former precede the latter in the middle field of the clause; cf. Cinque (1999) and Zwart (2011: §4.3.2). This generalization is illustrated by the two (b)-examples in (7) for the modal adverb waarschijnlijkprobably and the manner adverb hardloudly.

| a. | Relative order of adverbials in the middle field of the clause: |

| clause adverbial > VP adverbial |

| b. | dat | Jan waarschijnlijk | hard | lacht. | clause adverbial > VP adverbial | |

| that | Jan probably | loudly | laughs | |||

| 'that Jan is probably laughing loudly.' | ||||||

| b'. | * | dat | Jan hard | waarschijnlijk | lacht. | VP adverbial > clause adverbial |

| that | Jan loudly | probably | laughs |

However, the assumptions made so far would incorrectly predict that VP adverbials precede the internal arguments of the verb. Example (8a) shows that it is possible for the direct object de handleidingthe manual to follow the manner adverbial zorgvuldigmeticulously, but (8b) shows that the object can also precede the adverb. In fact, (8c) shows that the object can even precede clause adverbials such as waarschijnlijkprobably. The examples in (8) thus show that there is no strict order between the adverbials and the nominal arguments of the verb in Dutch, a phenomenon that has become known as scrambling. This word-order variation will be discussed in detail in Section 13.2, where we will argue that it results from optional leftward movement of the nominal arguments of the verb across the adverbials.

| a. | dat | Jan waarschijnlijk | zorgvuldig | de handleiding | leest. | |

| that | Jan probably | meticulously | the manual | reads | ||

| 'that Jan is probably reading the manual meticulously.' | ||||||

| b. | dat Jan waarschijnlijk de handleiding zorgvuldig leest. |

| c. | dat Jan de handleiding waarschijnlijk zorgvuldig leest. |

Note in passing that there are reasons to assume that the movement from which the order in the Dutch example (8b) is derived also occurs in English; there is even reason to assume that it is (almost) obligatory, since this would account for the fact that nominal objects usually precede manner adverbials in English; cf. Broekhuis (2008: §2/2011/2023) for detailed discussions. An alternative approach to this problem can be found in Ernst (2002: §4).

A useful test for recognizing VP adverbials is the paraphrase with a conjoined pronoun doet dat + adverb pronoun does that + adverb clause; cf. Van den Hoek (1972). This test is schematized in (9), where the arrow ⇒ should be read as “can be paraphrased as”: the first conjunct consists of the clause without the VP adverbial, which is used in the second conjunct as a modifier of the phrase doet dat, which replaces the verbal projection VP in the first conjunct.

| a. | [clause subject ... [VP ... adverbial ...]] ⇒ |

| b. | [[clause subjecti ... [VP ......]] & [pronouni [doet dat adverbial]]] |

The test is applied in the examples in (10) to intransitive and a transitive constructions; note in passing that the tense marking of the two conjuncts [±past] must match.

| a. | Jan lacht | hard. ⇒ | intransitive | |

| Jan laughs | loudly |

| a'. | [[Jani | lachtpresent] | en | [hiji | doetpresent | dat | hard]]. | |

| Jan | laughs | and | he | does | that | loudly |

| b. | Jan las | het boek | snel. ⇒ | transitive | |

| Jan read | the book | quickly |

| b'. | [[Jani | laspast | het boek] | en | [hij | deedpast | dat | snel]]. | |

| Jan | read | the book | and | he | did | that | quickly |

The (a)-examples in (11) show that the test works not only for (in)transitive constructions, but also for unaccusative constructions. The result is sometimes less felicitous, but in such cases it is often possible to use an en dat gebeurde + adverb paraphrase instead. This is illustrated by the (b)-examples for the adverb plotselingsuddenly: the paraphrase in (11b') contrasts sharply with the paraphrase ??De theepoti is gebroken, en hiji deed dat plotseling.

| a. | Jan/de trein | is op tijd | vertrokken. ⇒ | unaccusative | |

| Jan/the train | is on time | left | |||

| 'Jan/the train has left on time.' | |||||

| a'. | [[Jani/De treini | is vertrokken] | en | [hiji | deed | dat | op tijd]]. | |

| Jan/the train | is left | and | he | did | that | on time | ||

| 'The train has left and it did so on time.' | ||||||||

| b. | De theepot | is plotseling | gebroken. ⇒ | unaccusative | |

| the teapot | is suddenly | broken | |||

| 'The teapot has broken suddenly.' | |||||

| b'. | [[De theepot | is gebroken] | en | [dat | gebeurde | plotseling]]. | |

| the teapot | is broken | and | that | happened | suddenly | ||

| 'The teapot has broken and that happened suddenly.' | |||||||

Unfortunately, the test cannot be applied to all clauses with a VP adverbial, often for reasons not well understood, but it generally gives highly reliable results for clauses with an agentive subject and a non-stative/dynamic predicate.

Another test is based on the fact that VP adverbials restrict the denotation of the verbal predicate. As a result of this, the modified predicate entails the bare predicate, but not vice versa. This is illustrated in (12) for the intransitive verb lachento laugh and the unaccusative verb vertrekkento leave. For convenience, we will use the symbol ⊨ in this chapter to indicate that the entailment is unidirectional.

| a. | Jan lacht | hard. ⊨ | Jan lacht. | |

| Jan laughs | loudly | Jan laughs |

| a'. | Jan lacht. ⊭ Jan lacht hard. |

| b. | De trein | vertrekt | op tijd. ⊨ | De trein | vertrekt. | |

| the train | leaves | on time | the train | leaves |

| b'. | De trein vertrekt. ⊭ De trein vertrekt op tijd. |

That clause adverbials like the modal adverb waarschijnlijkprobably and the negative adverb nietnot do not restrict the denotation of the verbal predicate, but have some other function, is clear from the fact that they cannot be paraphrased by a conjoined pronoun doet dat clause, as shown in (13) for the examples in (1b); the arrow with a slash should be read here as “cannot be paraphrased as”.

| a. | Jan komt | waarschijnlijk. ⇏ | |

| Jan comes | probably |

| a'. | [[Jani komt] | en | [hiji | doet | dat | waarschijnlijk]]. | |

| Jan comes | and | he | does | that | probably |

| b. | Jan komt | niet. ⇏ | |

| Jan comes | not |

| b'. | [[Jani komt] | en | [hiji | doet | dat | niet]]. | |

| Jan comes | and | he | does | that | not |

Furthermore, example (14a) shows that clauses with a clause adverbial do not entail the corresponding clauses without the adverbial; for completeness, (14b) shows that the entailments do not hold in the opposite direction either.

| a. | Jan komt | waarschijnlijk/niet. ⊭ | Jan komt. | |

| Jan comes | probably/not | Jan comes |

| b. | Jan komt. ⊭ | Jan komt | waarschijnlijk/niet. | |

| Jan comes | Jan comes | probably/not |

Clause adverbials can have several functions: for example, waarschijnlijkprobably and nietnot can be equated with the logical operators ◊ and ¬, which scope over the entire proposition, as in the predicate calculus equivalents of (1b). This is illustrated in (15), where the double arrow indicates that the sentence and the logical formula express the same core meaning.

| a. | Jan komt | waarschijnlijk ⇔ ◊come(j) | |

| Jan comes | probably |

| b. | Jan komt | niet ⇔ ¬come(j) | |

| Jan comes | not |

That clause adverbials are external to the lexical domain of the clause is also made clear by the clause-adverbial test in (16), which shows that clause adverbials can even be external to the entire clause.

| a. | [clause ... adverbial [VP ......]] ⇒ |

| a'. | Het is adverbial zo [clause dat .... [VP ......]]. |

| b. | Jan lacht | waarschijnlijk. ⇒ | |

| Jan laughs | probably |

| b'. | Het | is waarschijnlijk | zo | dat | Jan lacht. | |

| it | is probably | the.case | that | Jan works |

For cases where the VP-adverbial and clause-adverbial tests do not give satisfactory results, we can appeal to the generalization (7a) from Subsection II that clause adverbials precede VP adverbials in the middle field of the clause: if an adverbial precedes an independently established clause adverbial, it cannot be a VP adverbial; if an adverbial follows a VP adverbial, it cannot be a clause adverbial. For example, all adverbials preceding the modal adverb waarschijnlijk or the negative adverb nietnot can be considered clause adverbials; cf. also Barbiers (2018).

The tests discussed above should be used with caution, as certain clause adverbials can sometimes be used with a more restricted scope. A well-known example is the negative adverb nietnot, which can express sentence negation with scope over the whole proposition expressed by the lexical domain of the clause, but can also express constituent negation with scope over a smaller constituent within the clause; cf. Section 13.3.2, sub IC. The (a)-examples in (17) show that in the latter case niet can occur in a conjoined pronoun doet dat-clause as modifier of the negated constituent. Whether or not Jan’s advent is indeed entailed by a sentence such as Jan komt niet volgende week may be a matter of debate, but it is clear that there is a strong tendency to accept it. The main point, however, is that in (17a) niet does not function as a VP adverbial, but as a modifier of the time adverbial; the paraphrase shows that niet volgende week functions as a complex VP adverbial. The (b)-examples show that more or less the same observations can be made for modal adverbs such as waarschijnlijkprobably; the paraphrase shows that waarschijnlijk morgen can function as a complex VP adverbial when morgen has a contrastive accent.

| a. | Jan komt | niet volgende week | (maar volgende maand). | |

| Jan probably | not next week | but next month | ||

| 'Jan does not come next week (but next month).' | ||||

| a'. | Jan komt | maar | hij | doet | dat | niet volgende week. | |

| Jan comes | but | he | does | that | not next week |

| b. | Jan komt | waarschijnlijk | morgen. | |

| Jan comes | probably | tomorrow | ||

| 'Jan will probably come tomorrow.' | ||||

| b'. | Jan komt | en | hij | doet | dat | waarschijnlijk morgen. | |

| Jan comes | and | he | does | that | probably tomorrow |

Some adverbial phrases can be used either as clause adverbials or as VP adverbials, depending on their position in the middle field of the clause. We will illustrate this here with temporal adverbials, but the same could be shown for spatial adverbials. Consider the punctual adverbial om drie uurat 3 oʼclock in (18a); the fact that the pronoun doet dat + adverb paraphrase in (18b) is possible and the entailment in (18c) is valid shows that we are dealing with a VP adverbial.

| a. | Jan vertrekt | (waarschijnlijk) | om drie uur. | |

| Jan leaves | probably | at 3 o’clock | ||

| 'Jan will (probably) leave at 3 o'clock.' | ||||

| b. | Jan vertrekt om drie uur. ⇒ [[Jani vertrekt] en [hiji doet dat om drie uur]]. |

| c. | Jan vertrekt om drie uur. ⊨ Jan vertrekt. |

That the temporal adverbial om drie uur functions as a VP adverbial in (18a) is consistent with the fact that it follows the modal adverb waarschijnlijkprobably. However, example (19a) shows that it is not always the case that temporal adverbials must follow the clause adverbials. According to the generalization in (7a) that VP adverbials cannot precede clause adverbials, the temporal adverbial morgentomorrow must be a clause adverbial, which is confirmed by the fact that the scope paraphrase in (19b) is acceptable.

| a. | Jan vertrekt | morgen | waarschijnlijk. ⇒ | |

| Jan leaves | tomorrow | probably | ||

| 'Jan will probably leave tomorrow.' | ||||

| b. | Het | is | morgen | waarschijnlijk | zo | dat Jan vertrekt. | |

| it | is | tomorrow | probably | the.case | that Jan leaves |

The hypothesis that the temporal adverbials in (18a) and (19a) have different syntactic/semantic functions is supported by the fact, illustrated in (20a), that they can occur together in a single clause. Example (20b) shows that we find similar facts for spatial adverbials.

| a. | Jan zal | morgenclause | waarschijnlijk | om drie uurVP | vertrekken | |

| Jan will | tomorrow | probably | at three hour | leave | ||

| 'Tomorrow, Jan will probably leave at 3 oʼclock.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan | zal | in Amsterdamclause | waarschijnlijk | bij zijn tanteVP | logeren. | |

| Jan | will | in Amsterdam | probably | with his aunt | stay | ||

| 'In Amsterdam, Jan will probably stay at his aunt's place.' | |||||||

The discussion above shows that we should be aware that adverbials can sometimes perform multiple syntactic/semantic functions in a clause, i.e. as VP adverbial or as clause adverbial, and that we should therefore not jump to conclusions based on the application of a single test; Section 8.2.3 will return to this issue in more detail.