- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section discusses focus and topic movement, which target the specifier of a Foc(us)P and Top(ic)P, respectively, as shown in (113). The fact that the movements in (113) involve a PP, which moreover functions as a subpart of a clausal constituent, immediately shows that we are dealing with A'-movement. For simplicity we will represent the lexical domain of the clause as [LD ... V ...] instead of [vP ... v [VP ... V ...]], and ignore traces of subjects if they are not directly relevant for the discussion; cf. the introduction to Section 13.3.

| a. | dat | Marie [FocP | [op ]i Foc [LD [AP | erg dol ti] | is]]. | |

| that | Marie | of Peter | very fond | is | ||

| 'that Marie is very fond of Peter.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | weet | niet | wat | Marie van Jan | vindt, | maar | ik | weet | wel ... | dat | ze [TopP | [op Peter]i Top [LD [AP | erg dol ti] | is]]. | ||||||

| I | know | not | what | Marie of Jan | considers, | but | I | know | aff | that | she | of Peter | very fond | is | |||||||

| 'I do not know how Marie feels about Jan, but I do know that she is very fond of Peter.' | |||||||||||||||||||||

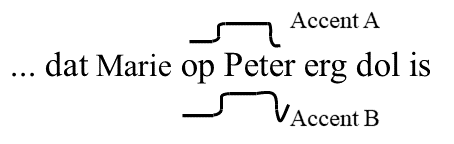

The contrastive phrases in (113) are phonetically characterized by a specific accent that involves a high pitch followed by a sudden drop in pitch. The two cases differ in that the contrastive focus accent, sometimes called the A-accent, ends after the drop in pitch, while the contrastive topic accent, sometimes called the B-accent, has an additional rise in pitch; cf. Jackendoff (1972: §6.7), Büring (2007), and Neeleman & Van de Koot (2008). The development of the two pitch accents is shown in (114) by lines: in the examples, words with an A-accent are marked by small caps in italics, words with a B-accent are not marked by small caps, but by double underlining and italics; cf. (113).

|

Semantically speaking, contrastive accent evokes a set of alternative propositions. A common intuition is that contrastive focus involves “some kind of contrast between the Focus constituent and alternative pieces of information which may be explicitly presented or presupposed” (Dik 1997:332). This can be formally expressed by assuming that focus adds an additional semantic value (hereafter: focus value) to the regular semantic value (hereafter: ordinary value) of a clause; cf. Rooth (1997). Thus, while the ordinary value of the sentence Jan bezoekt MarieJan visits Marie is simply the proposition given in (115a&b), the added focus values are sets of propositions, as indicated in the primed examples, in which the value of the variables x and y is taken from the set of (contextually defined) persons E.

| a. | [Jan bezoekt [Focus Marie]]o = visit(j,m) | ordinary value |

| a'. | [Jan bezoekt [Focus Marie]]F = {visit(j,x) | x ɛ E} | focus value |

| b. | [[Focus Jan] bezoekt Marie]o = visit(j,m) | ordinary value |

| b'. | [[Focus Jan] bezoekt Marie]F = {visit(y,m) | y ɛ E} | focus value |

The function of non-contrastive (new information) focus is that the speaker fills an information gap on the part of the addressee by adding or selecting a proposition to or from the focus value; crucially, the speaker does not intend to imply anything for the alternative propositions from the focus value. By using the A-accent, on the other hand, the speaker implies that the ordinary value of the clause is counter-presuppositional. An utterance such as Jan bezoekt Marie then opposes the ordinary value of the clause in (115a) to other propositions from the focus value in (115a') that the speaker assumes that the addressee takes to be true, i.e. the speaker implies that Jan did not visit at least one person from E; cf. also Neeleman & Vermeulen (2012). Note that the nature of the counter-presuppositional relation can be further specified by focus particles like alleenonly and ooktoo; we will return to this in Subsection IC. By using the contrastive B-accent, the speaker implies that there is at least one other potential discourse topic that could have been addressed. For example, the plurality of the finite verb in question (116a) implies that the set of contextually defined persons E contains at least two persons who are expected to be invited to the party. The answer in (116b) does not answer the question, but asserts something about one of the persons from E; cf. Büring (2007), Neeleman & Van de Koot (2008), and Neeleman & Vermeulen (2012).

| a. | Wie | zijn | er | uitgenodigd | voor het feest? | question | |

| who | are | there | invited | for the party | |||

| 'Who are invited to the party?' | |||||||

| b. | Geen idee. | Ik | weet | alleen | dat | Peter | niet | kan | komen. | response | |

| no idea | I | know | only | that | Peter | not | can | come | |||

| 'No idea. I only know that Peter cannot come.' | |||||||||||

The examples in (113) have already shown that contrastive foci and topics are syntactically characterized by the fact that they can be displaced. This property will be examined in more detail in the following subsections. Subsection I begins with a discussion of focus movement, which is followed by a discussion of topic movement in Subsection II. The study of focus and topic movement is relatively recent, so it is not surprising that there are still a large number of controversial issues, some of which will be discussed in Subsection III.

The direct objects in responses such as (117b&c) are assigned regular sentence accent (indicated by small caps) and are therefore part of the new-information focus. They can still be interpreted as contrastive foci in the sense that they exclude values of the variable x other than Marie. Note, however, that in these cases the contrastive interpretations are entirely pragmatic in nature, as Grice’s cooperative principle requires that the responses in (117) be complete; cf. Neeleman & Vermeulen (2012).

| a. | Wie | heeft | Jan/hij | bezocht? | question: ?x(Jan/he has visited x) | |

| who | has | Jan/he | visited | |||

| 'Who has Jan/he visited?' | ||||||

| b. | Hij | heeft | een vriendin | bezocht: | Marie. | answer | |

| he | has | a friend | visited | Marie | |||

| 'He has visited a lady friend: Marie.' | |||||||

| c. | Jan heeft | Marie | bezocht. | answer | |

| Jan has | Marie | visited | |||

| 'Jan has visited Marie.' | |||||

The cases of contrastive foci to be discussed in this subsection are different in that they are characterized as contrastive by the phonetic property that they carry a contrastive A-accent, and by the syntactic property that they can be moved leftward by focus movement. Subsection A will begin by discussing the landing site of focus movement, Subsection B will argue that focus movement is A'-movement, and Subsection C will conclude by arguing that focus movement is obligatory, just like other semantically motivated movements.

This subsection discusses the landing site of focus movement. Following the line of research in Rizzi (1996) and Haegeman (1995), one possibility would be to postulate a focus phrase (FocP) in the middle field of the clause, the specifier of which is a designated landing site for focus movement. Neeleman & Van de Koot (2008) assumes that focus movement is motivated by the need to assign scope to the focus phrase or, in their formulation, to distinguish contrastive foci from the backgrounds against which they are evaluated; cf. Barbiers (2010) for an alternative proposal. Since we have seen that contrastive foci evoke a set of alternative propositions, we can safely conclude that the background contains at least the lexical domain of the clause: this implies that FocP is part of the verb’s functional domain.

| ... [FocP XPi Foc [ ... [LD ... ti ...]]] |

Neeleman & Van de Koot argues against hypothesis (118) insofar as it relies on a designated target position for focus movement, claiming that focus movement can target any position from which the contrastively focused phrase can take scope over its background. The advantage of this proposal is that it can easily account for examples such as (119) by saying that the word-order difference between the two examples reflects a scopal difference between the focused phrase and the modal adverbial waarschijnlijkprobably: the adverbial is in the scope of the focus in (119a), but not in (119b).

| a. | dat | ze | [op ]i | waarschijnlijk [LD [AP | erg dol ti] | is]. | |

| that | she | of Peter | probably | very fond | is | ||

| 'that she is probably very fond of .' | |||||||

| b. | dat | ze waarschijnlijk | [op ]i [LD [AP | erg dol ti] | is]. | |

| that | she probably | of Peter | very fond | is | ||

| 'that she is probably very fond of .' | ||||||

One possible problem with the hypothesis that the contrastively focused phrase can target any position from which it can take scope over the lexical domain of the clause is that it seems to overgenerate. For instance, the examples in (120b&c) show that the target position of focus movement cannot follow a negation or precede a weak subject pronoun in the regular subject position.

| a. | dat | ze | [op ]i | niet [LD [AP | erg dol ti] | is]. | |

| that | she | of Peter | not | very fond | is | ||

| 'that she probably is not very fond of .' | |||||||

| b. | * | dat | ze | niet | [op ]i [LD [AP | erg dol ti] | is]. |

| that | she | not | of Peter | very fond | is |

| c. | * | dat | [op ]i | ze | niet [LD [AP | erg dol ti] | is]. |

| that | of Peter | she | not | very fond | is |

The schematic representation in (121a) summarizes the positions where the contrastively focused PP op Peter can and cannot be found. Assuming that focus movement targets the specifier position of a FocP, we can account for this in at least two ways. One possibility is to adopt the representation in (121b), according to which there are two FocPs, one relatively high and one relatively low in the middle field of the clause; cf. Belletti (2004), Aboh (2007), and Zubizarreta (2010). Another possibility is that there is only a single FocP, but that the modal adverb can be inserted either above or below the FocP depending on its scope relative to the contrastive focus, as in (121b').

| a. | dat <*PPi> hij <PPi> waarschijnlijk <PPi> niet <*PPi> [LD [AP erg dol ti] is]. |

| b. | dat hij .. [FocP .. Foc [.. waarschijnlijk [FocP .. Foc [NegP .. Neg [LD ...]]]]] |

| b'. | dat hij <waarschijnlijk> [FocP .. Foc [.. <waarschijnlijk> [NegP .. Neg [LD ...]]]] |

Since the debate about the landing site of focus movement is still in its early stages, we will not evaluate the three proposals further, but simply assume for the sake of concreteness that focus movement targets the specifier of FocP.

This subsection reviews a number of arguments for assuming that focus movement is A'-movement. A first and conclusive argument is that focus movement can affect non-nominal categories. It has also been argued that focus movement can violate certain word-order restrictions that constrain A-movement, but we will see that there are certain difficulties with this argument. A third argument found in the literature is that focus movement is not clause-bound.

A-movement is restricted to nominal categories; cf. Section 13.2, sub III. The fact that focus movement can also affect PPs, as illustrated again in (122b), is therefore sufficient to conclude that we are dealing with A'-movement. Example (122c) further supports this conclusion by providing an example in which an adjectival complementive has undergone focus movement.

| a. | dat | Jan waarschijnlijk | [het ]i | niet ti | wil | kopen. | nominal object | |

| that | Jan probably | the book | not | wants | buy | |||

| 'that Jan probably does not want to buy the book.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | Jan waarschijnlijk | [op ]i | niet ti | wil wachten. | adpositional object | |

| that | Jan probably | for father | not | wants wait | |||

| 'that Jan probably does not want to wait for .' | |||||||

| c. | dat | Jan het | waarschijnlijk | [ belangrijk]i | niet ti | vindt. | complementive | |

| that | Jan it | probably | that important | not | considers | |||

| 'that Jan probably does not consider this important.' | ||||||||

The claim that focus movement is A'-movement is consistent with the conclusion that focus movement can target a position to the right of the modal adverbials, because Section 13.2 has shown that nominal argument shift must target a position to the left of the modal adverbials. This contrast between A and A'-movement can be highlighted by the VP-topicalization constructions in (123), which show that stranding of the direct object in a position after the clause adverbials requires it to be contrastively focused.

| a. | [VP ti | Kopen] | wil | Jan | <het boeki> | waarschijnlijk <*het boeki> tVP. | |

| [VP ti | buy | wants | Jan | the book | probably |

| b. | [VP ti | Kopen] | wil | Jan waarschijnlijk | het i tVP. | |

| [VP ti | buy | wants | Jan probably | the book |

It can also be illustrated quite nicely by considering the placement of strong (phonetically non-reduced) referential personal pronouns like zijshe and haarher; such pronouns may only occur after modal adverbials if they have an A-accent.

| a. | dat | <zij/ > | waarschijnlijk < /*zij> | het boek | gekocht | heeft. | |

| that | she/she | probably | the book | bought | has | ||

| 'that she/ probably has bought the book' | |||||||

| b. | dat | Jan | <haar/ > | waarschijnlijk < /*haar> | wil | helpen. | |

| that | Jan | her/her | probably | wants | help | ||

| 'that Jan probably wants to help her/ .' | |||||||

Finally, the fact that nominal argument shift and focus movement target different landing sites is highlighted by the fact that [-human] referential personal pronouns can never occur after the modal adverbials, for the simple reason that they are phonetically obligatorily reduced; to contrastively focus an inanimate entity, the demonstrative deze/diethis/that is used.

| a. | dat | hij | <de > | waarschijnlijk <de > | gekocht | heeft. | |

| that | he | the car | probably | bought | has | ||

| 'that he probably has bought the car.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | hij | <ʼm/ > | waarschijnlijk < /* /*ʼm> | gekocht | heeft. | |

| that | he | him/dem | probably | bought | has | ||

| 'that he probably has bought .' | |||||||

Another argument for an A'-movement analysis of focus movement has to do with word order. Section 13.2, sub IC, has shown that nominal argument shift cannot affect the unmarked order of nominal arguments (agent > goal > theme) in Dutch. Neeleman & Van de Koot (2008), Van de Koot (2009), and Neeleman & Vermeulen (2012) claim that focus movement is capable of changing the order of nominal arguments, as illustrated in (126), and that this supports the claim that we are dealing with A'-movement.

| a. | % | Ik | geloof | [dat | i | Jan Marie ti | gegeven | heeft]. |

| I | believe | that | this book | Jan Marie | given | has |

| b. | % | Ik | geloof | [dat | Jan i | Marie ti | gegeven | heeft]. |

| I | believe | that | Jan this book | Marie | given | has |

| c. | Ik | geloof | [dat | Jan Marie | gegeven | heeft]. | ||

| I | believe | that | Jan Marie | this book | given | has | ||

| 'I believe that Jan has given Marie this book.' | ||||||||

The argument is not entirely convincing; the fact that this kind of order preservation does not hold for German nominal argument shift shows that it is not a defining property of nominal argument shift; cf. Section 13.2, sub IC. Furthermore, the judgments made in the studies by Neeleman and his collaborators are controversial, since some speakers of Dutch (including the authors of this work) reject the examples in (126a&b) with the indicated intonation pattern; cf. also Neeleman & Van de Koot (2008:fn.2) and Van de Koot (2009:fn.4). A simpler example, also rejected by some of our informants, is given in (127). In our view, the unclear acceptability status of (126a&b) and (127a) makes it impossible to draw any firm conclusion; it remains to be seen whether such examples should be considered part of the standard variety of Dutch, but we will leave this question to future research.

| a. | % | Ik | geloof | [dat | i | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]. |

| I | believe | that | this book | Jan | read | has |

| b. | Ik | geloof | [dat | Jan i | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| I | believe | that | Jan this book | read | has | ||

| 'I believe that Jan has read .' | |||||||

To avoid confusion, we should note that the examples marked with % are acceptable when the contrastively accented phrases are given a B-accent, in which case we are dealing with a contrastive topic; Subsection II will provide more data showing that topic movement can indeed affect the unmarked order of nominal arguments under certain conditions.

Example (128a) shows that focus movement can change the unmarked order of nominal and prepositional objects: while prepositional indirect objects usually follow direct objects, focus movement of the former can easily cross the latter. Note, however, that this requires the direct object to follow the modal adverb: the examples in (128b&c) show that object shift of het boek has a degrading effect on focus movement regardless of whether the focused phrase precedes or follows the modal adverb; we added the adverb niet to (128c) to make focus movement visible. Note that (128b) becomes perfectly acceptable when the PP is assigned a B-accent, showing that topic movement can cross a shifted object.

| a. | dat | Jan | <aan > | waarschijnlijk <aan > | het boek | zal | geven. | |

| that | Jan | to Peter | probably | the book | will | give | ||

| 'that Jan will probably give the book to Peter.' | ||||||||

| b. | ?? | dat | Jan | aan | het boek | waarschijnlijk | zal | geven. |

| that | Jan | to Peter | the book | probably | will | give | ||

| 'that Jan will probably give the book to .' | ||||||||

| c. | dat | Jan het boek | waarschijnlijk | <??aan > | niet <aan > | zal | geven. | |

| that | Jan the book | probably | to Peter | not | will | give | ||

| 'that Jan probably will not give the book to .' | ||||||||

This subsection has shown that the claim that focus movement is able to change the unmarked order of nominal arguments in standard Dutch is controversial; whether this property could be used as an argument for the claim that focus movement is A'-movement is also not clear, since order preservation seems to be an accidental property of nominal argument shift in Dutch (not German).

A'-movement such as wh-movement differs from A-movement in that it allows extraction from finite clauses under certain conditions (so-called long movement). Neeleman (1994a/1994b) and Barbiers (1998/1999/2002/2018) have shown that there is also long focus movement: the primed examples in (129) illustrate that foci can target a focus position in the middle field of a matrix clause. The percentage signs are used to indicate that this kind of long focus movement is not normally found in written language, but can be found in colloquial speech; cf. Zwart (1993:200).

| a. | Ik | had | gedacht | [dat | het feest | in de tuin | zou | zijn]. | |

| I | had | thought | that | the party | in the garden | would | be | ||

| 'I had thought that the party would be in the garden.' | |||||||||

| a'. | % | Ik | had | [in de ]i | gedacht | [dat | het feest ti | zou | zijn]. |

| I | had | in the garden | thought | that | the party | would | be | ||

| 'I had thought that the party would be in the .' | |||||||||

| b. | Ik | had | gedacht | [dat | Jan een boek | zou | kopen]. | |

| I | had | thought | that | Jan a book | would | buy | ||

| 'I had thought that Jan would buy a book.' | ||||||||

| b'. | % | Ik | had | [een ]i | gedacht | [dat | Jan ti | zou | kopen]. |

| I | had | a book | thought | that | Jan | would | buy | ||

| 'I had thought that Jan would buy a .' | |||||||||

That the landing site of the foci in the primed examples is external to the embedded clause is clear from the fact that the foci precede the clause-final main verb of the matrix clause. Section 11.3.3, sub II, has shown that topicalization is impossible in Dutch embedded clauses and this correctly predicts that foci cannot immediately follow clause-final verbs; cf. the structures in example (130).

| a. | * | Ik | had gedacht | [[in de ]i | dat | het feest ti | zou | zijn]. |

| I | had thought | in the garden | that | the party | would | be |

| b. | * | Ik | had | gedacht | [[een ]i | dat | Jan ti | zou | kopen]. |

| I | had | thought | a book | that | John | would | buy |

Although the primed examples in (129) may be objectionable to some speakers, the sharp contrast with the examples in (130) shows that they are at least marginally possible in standard Dutch. This conclusion is also supported by the fact that the primed examples in (129) are clearly much better than the corresponding examples in (131) with the factive verb betreurento regret. This contrast shows that long focus movement is only possible in certain bridge-verb contexts.

| a. | * | Ik | had | [in de ]i | betreurd | [dat | het feest ti | zou | zijn]. |

| I | had | in the garden | regretted | that | the party | would | be |

| b. | * | Ik | had | [een ]i | betreurd | [dat | Jan ti | zou | kopen]. |

| I | had | a book | regretted | that | John | would | buy |

There are reasons to assume that long focus movement is like long wh-movement in that it has to pass through the initial position of the embedded clause. A somewhat weak argument for this claim is that the direct object een boeka book in the (b)-examples in (129) can easily cross the subject, as this is a well-established property of A'-movements targeting the clause-initial position. A stronger argument is that long focus movement cannot co-occur with long wh-movement, as shown by the examples in (132): the examples in (132b&c) first show that wh-phrases and foci can be extracted from the embedded clause in (132a), while (132d) shows that they cannot be extracted simultaneously. This would immediately follow if all long movements had to pass through the clause-initial position of the embedded clause: long wh-movement would then block long focus movement (or vice versa), because this position can only be filled by a single (trace of a) constituent (but see Barbiers (2002) for a different account).

| a. | Ik | had gedacht | [dat | Jan morgen | in de tuin | zou | werken]. | |

| I | had thought | that | Jan tomorrow | in the garden | would | work | ||

| 'I had thought that Jan would work in the garden tomorrow.' | ||||||||

| b. | Waari | had | jij | gedacht | [dat | Jan morgen ti | zou | werken]? | |

| where | had | you | thought | that | Jan tomorrow | would | work | ||

| 'Where had you thought that Jan would work tomorrow?' | |||||||||

| c. | % | Ik | had j | gedacht | [dat | Jan tj | in de tuin | zou | werken]. |

| I | had tomorrow | thought | that | Jan | in the garden | would | work | ||

| 'I had thought that Jan would work in the garden .' | |||||||||

| d. | * | Waari | had | jij | j | gedacht | [dat Jan tj ti | zou | werken]? |

| where | had | you | tomorrow | thought | that Jan | would | work |

The movement analysis of the primed examples in (129) is also used to account for the fact that the primeless and primed examples are propositionally equivalent. It has already been noted in Jespersen (1927:53) that the same seems to hold for negative examples as in (133).

| a. | Ik | denk | [dat | het | niet | gaat | regenen]. | |

| I | think | that | it | not | goes | rain | ||

| 'I think that it is not going to rain.' | ||||||||

| b. | Ik | denk | niet | [dat | het | gaat | regenen]. | |

| I | think | not | that | it | goes | rain | ||

| 'I do not think that it is going to rain.' | ||||||||

The equivalence of ¬P(x,p) and P(x,¬p), where x stands for the subject of the matrix predicate P and p for the proposition expressed by its complement clause, does not hold for all matrix predicates, but only for predicates that are non-factive. Horn (2001) distinguishes the following subclasses: opinion (to think/expect), perception (to seem/look like); probability (to be likely), intention and volition (to want/choose), and judgment and (weak) obligation (must/to advise). Klooster (2003), in a discussion of Dutch, concludes that the equivalence “obtains in sentences with negated non-factive verbs expressing, together with their negation, a negative attitude towards a hypothetical state's or event's being or becoming fact”. Already early in the history of transformational grammar the two constructions in (133) were related by long movement, now called neg-raising: cf. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_raising for references and an overview of different syntactic approaches, and Klooster (2003) for an alternative approach.

De Schepper et al. (2014) shows, based on the Corpus of spoken Dutch, that a similar phenomenon exists for pragmatic markers, including the affirmative counterpart wel of the negative adverb niet. Example (134) provides a case with the sentence adverbial eigenlijk; in both cases, the adverb is construed with the embedded proposition. The appendix to the article mentions the following additional cases: even (marker of kindness), gewoonjust, inderdaadindeed, meerrather, ooktoo, sowiesoanyway, tochstill. It is further argued that the matrix predicate must be subjective in the sense that it expresses the speaker’s personal view about the objective content of the embedded clause.

| a. | dan | zie | je | [dat | ’t | eigenlijk | steeds | erger | wordt] | |

| then | see | you | that | it | actually | all.the.time | worse | becomes | ||

| 'then you see that it is actually getting worse.' | ||||||||||

| b. | dan | zie | je | eigenlijki | [dat | ’t ti | steeds | erger | wordt] | |

| then | see | you | actually | that | it | all.the.time | worse | becomes | ||

| 'then you see that it is actually getting worse.' | ||||||||||

Barbiers (2018) characterizes the set of pragmatic markers as affirmative evaluative (or polarity) adverbs and considers examples such as (134b) as positive counterparts of NEG-raising constructions such as (133b). This can be supported at least for the affirmative marker wel by examples such as (135), where raised wel stands in clear opposition to the non-raised negative adverb niet.

| Ik | denk | [dat | ze | niet | zullen | komen], | ||

| I | think | that | they | not | will | come |

| maar | ik | denk | wel | [dat | ze | zullen | bellen]. | ||

| but | I | think | aff | that | they | will | call | ||

| 'I think that they will not come, but I do think they will call.' | |||||||||

De Schepper et al. (2014) further argues that the matrix predicate must be subjective in the sense that it expresses the speaker’s personal view about the objective content of the embedded clause. This is also the position taken by Barbiers (2018) with respect to speaker-oriented adverbial phrases such as eerlijk gezegdhonestly in (136): a speaker-oriented adverbial such as eerlijk gezegd must have scope over the main clause independently of its position; cf. also De Schepper et al. (2014).

| a. | Ik | denk | [dat | ze | eerlijk gezegd | voor Rooney | gaan]. | |||

| I | think | that | they | honestly said | for Rooney | go | ||||

| 'Honestly, I think they will go for Rooney.' | ||||||||||

| b. | Ik | denk | eerlijk gezegd | [dat | ze | voor Rooney | gaan]. | |

| I | think | honestly said | that | they | for Rooney | go | ||

| 'Honestly, I think they will go for Rooney.' | ||||||||

Barbiers further notes a number of systematic properties in pairs such as (136). First, the matrix verb must be non-factive in order to allow a matrix interpretation of an adverbial phrase in the embedded clause: the verb denken ‘to think’ in (136a) cannot be replaced by the factive verb wetento know). Second, an embedded adverbial phrase must have speech act properties in order to receive a matrix interpretation: the adverbial eerlijk gezegd in (136a) cannot be replaced by the speaker-oriented adverb helaas ‘unfortunately’ or by sentence adverbials of any other kind. For example, the frequency adverbial altijd ‘always’ is restricted to its minimal clause.

| a. | Ik | denk | [dat | ik | altijd | ga | winnen]. | |

| I | think | that | I | always | go | win | ||

| 'I think: I am always going to win.' | ||||||||

| b. | Ik | denk | altijd | [dat | ik | ga | winnen]. | |

| I | think | always | that | I | go | win | ||

| 'I always think: I am going to win.' | ||||||||

Third, the reference of the subject of the matrix clause must include the speaker (regardless the position of the adverbial); the subject pronoun ik can be replaced by wijwe’, but not by jij/jullie ‘you’ or hij/zij ‘he/they’ (but see Fortuin 2022:10-11). For further discussion and an attempt at analysis in terms of the Cinque hierarchy of adverbial phrases discussed in Section 8.2, see Barbiers (2018:§2).

The discussion above has shown that long A'-movement of an element into the middle field of the matrix clause is not a phenomenon restricted to focus-movement but is also common in the case of negation and pragmatic markers. However, the three subtypes seem to impose their own restrictions on the matrix predicate, which shows that we are not dealing with a purely syntactic phenomenon, but that semantic and pragmatic factors also play a role; cf. De Schepper et al. (2014), Fortuin (2022) and Barbiers (2022) for further discussion of this issue and the possible consequences for the analysis.

There are good reasons to think that A'-movement is obligatory because it is needed to derive structures that can be interpreted by the semantic component of the grammar. For example, Section 11.3.1.1, sub II, has argued that wh-movement in wh-questions is obligatory because it derives an operator-variable chain in the sense of predicate calculus. And Section 13.3.1, sub II, has argued that negation movement is obligatory in order to assign scope to sentence negation. In light of this, we can hypothesize that focus movement is necessary to assign scope to contrastively focused phrases (unless there is some other means of indicating scope). Languages such as Hungarian, in which contrastive foci are obligatorily moved into a position left-adjacent to the finite verb, seem to support this hypothesis; cf. É. Kiss (2002: §4). Languages such as English, which seem to mark contrastive focus only by intonation, are possible problems for the hypothesis, but since it has been argued that English does have focus movement in at least some constructions (Kayne 1998), it remains to be seen whether languages such as English are true counterexamples. This subsection argues that focus movement is normally obligatory in standard Dutch by appealing to constructions with focus particles of two types: counter-presuppositional focus particles (alleenonly, ookalso, etc.) and scalar focus particles (alalready, nogstill, maaronly, etc.).

A possible problem for the hypothesis that focus movement is obligatory in standard Dutch is that it is sometimes possible to leave constituents with an A-accent in their original position. This is illustrated by the two examples in (138) and suggests that focus movement is optional. Of course, this conclusion is only valid if the two examples are semantically equivalent, which does not seem to be the case.

| a. | dat | Jan [FocP | [op ]i Foc [LD [AP | erg dol ti] | is]]. | |

| that | Jan | of Peter | very fond | is | ||

| 'that Jan is very fond of Peter.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan [AP | erg dol | op ] | is. | |

| that | Jan | very fond | of Peter | is | ||

| 'that Jan is very fond of Peter.' | ||||||

Before showing that the two examples in (138) are not fully equivalent, we will first consider example (139a), which clearly has two readings: the contrastive focus can be restricted to the direct object only, in which case the sentence expresses that there are certain other things in the discourse domain that Jan did not read, or it can extend to the verb phrase, in which case the sentence expresses that there were certain things that Jan did not do. The examples in (139b&c) show that the two readings evoke different word orders when the negative adverb niet is present. The clearest case is (139b), where the contrastive focus is restricted to the moved direct object. Example (139c) is somewhat more complicated, as it again allows two readings, one with contrastive focus on the verb phrase and one with contrastive focus on the noun phrase. This can be explained if we assume that in both cases we are dealing with constituent negation: Hij heeft niet de roman gelezen, maar het gras gemaaid he has not read the novel, but mowed the grass versus Hij heeft niet de roman gelezen, maar het gedicht he did not read the novel but the poem.

| a. | dat | Jan | waarschijnlijk | de | gelezen | heeft. | |

| that | Jan | probably | the novel | read | has | ||

| 'that Jan has probably read the novel.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | Jan | waarschijnlijk | de | niet | gelezen | heeft. | |

| that | Jan | probably | the novel | not | read | has | ||

| 'that Jan has probably not read the novel.' | ||||||||

| c. | dat | Jan | waarschijnlijk | niet | de | gelezen | heeft. | |

| that | Jan | probably | not | the novel | read | has | ||

| 'that Jan has probably not read the novel.' | ||||||||

The crucial point for our present discussion is that (140a) is more suitable for expressing the restrictive focus reading than (140b). The former case evokes alternative propositions expressing that there are persons other than Peter whom Jan is very fond of, whereas (140b) rather expresses that the state of being fond of Peter does not apply to Jan, as is clear from the fact that it can easily be contrasted with an alternative state that does apply (here: to hate Peter), but not with the PP op Marie.

| a. | dat | Jan | [op ]i | niet [[AP | erg dol ti] | is], | maar | ( ) | op . | |

| that | Jan | of Peter | not | very fond | is | but | aff | of Marie | ||

| 'that Jan is not very fond of Peter, but is very fond of Marie.' | ||||||||||

| b. | dat | Jan niet [[AP | erg dol | op ] | is], | maar | ʼm | /??op . | |

| that | Jan not | very fond | of Peter | is | but | him | hates | ||

| 'that Jan is not very fond of Peter, but hates him.' | |||||||||

For completeness’ sake, note that the PP in (140a) must precede the negative adverb nietnot: cf. *dat Jan niet op PETER erg dol is. This is expected if it targets the specifier of FocP; cf. the discussion of (120) and (121).

Although constituents carrying an A-accent can apparently remain in situ, the discussion above suggests that this disfavors the restrictive focus interpretation. Of course, more needs to be said about the cases of constituent negation before we can conclude that focus movement is obligatory, but one thing is already clear: because nietnot is not located in the specifier of NegP when it expresses constituent negation, its location does not say much about the position of the contrastively focused phrase that follows it. The next subsection will show that there are reasons to assume that when the negative adverb niet expresses constituent negation, it functions as a focus particle and that the contrastively focused phrase following it normally occupies the specifier of FocP.

Focus adds an additional semantic value (hereafter: focus value) to the regular semantic value (hereafter: ordinary value) of a clause, as indicated again in (141) for the sentence Jan bezoekt MarieJan is visiting Marie.

| a. | [Jan | bezoekt [Focus Marie]]o = visit(j,m) | ordinary value |

| a'. | [Jan bezoekt [Focus Marie]]F = {visit(j,x) | x ɛ E} | focus value |

| b. | [[Focus Jan] bezoekt Marie]o = visit(j,m) | ordinary value |

| b'. | [[Focus Jan] bezoekt Marie]F = {visit(y,m) | y ɛ E} | focus value |

The function of non-contrastive (new information) focus is that the speaker simply fills an information gap on the part of the addressee by adding a proposition to or selecting a proposition from the focus value of the clause; the speaker does not intend to imply anything for the alternative propositions. Contrastive focus, on the other hand, is counter-presuppositional in the sense that it aims at modifying a subset of propositions that the speaker presupposes to be considered true by the addressee; cf. the discussion of (115) in the introduction to this section. The modification can take different forms; we will slightly adapt Dik’s (1997; §13.4) classification by making the four-way distinction in Table 1, where (PA)S stands for the set of propositions presumably held by the addressee, PS stands for the modified set proposed by the speaker, and expression type refers to the English focus particles prototypically used to express the different subtypes; all subtypes are marked by an A-accent, which is represented by an exclamation mark.

| (PA)S | modified set PS | expression type | |

| correcting | X | Y | not X, but Y! |

| expanding | X | X and Y | also Y! |

| restricting | X and Y | X | only X! |

| selecting | X or Y | X | X! |

Correcting focus is the most complex case, because correction involves two simultaneous actions: rejection and replacement. The examples in (142) show that the speaker can perform both actions explicitly, but that he can also leave one of them implicit. The act of rejection is performed by constituent negation, i.e. the focus particle nietnot, in combination with the A-accent, while the A-accent suffices to perform the act of replacement. Note that (142b) is special in that it requires a secondary accent on the negative adverb niet.

| Jan | heeft | het boek | gekocht. | ||

| Jan | has | the book | bought | ||

| 'Jan has bought the book.' | |||||

| a. | Nee, | hij | heeft | niet | het | gekocht, | maar | de . | correction | |

| no | he | has | not | the book | bought | but | the record |

| b. | Nee, | hij | heeft | niet | het | gekocht. | rejection | |

| no | he | has | not | the book | bought |

| c. | Nee, | hij | heeft | de | gekocht. | replacement | |

| no | he | has | the record | bought |

Expanding, restricting and selecting focus are illustrated in (143), all of which are marked by the A-accent. Expansion is prototypically expressed by the focus particle ookalso and restriction by alleenonly, while selection is like replacement in that it does not involve the use of a focus particle.

| a. | Jan | heeft | het boek | gekocht. | |

| Jan | has | the book | bought |

| a'. | Ja, | maar | hij | heeft | ook | de | gekocht. | expansion | |

| yes | but | he | has | also | the record | bought | |||

| 'Yes, but he has also bought the record.' | |||||||||

| b. | Jan | heeft | het boek en de plaat | gekocht. | |

| Jan | has | the book and the record | bought |

| b'. | Nee, | hij | heeft | alleen | de | gekocht. | restriction | |

| no | he | has | only | the record | bought |

| c. | Heeft | Jan | het boek of de plaat | gekocht? | |

| has | Jan | the book or the record | bought |

| c'. | Hij | heeft | de | gekocht. | selection | |

| he | has | the record | bought |

In the primed examples in (143), the focus particles ook and alleen are associated with nominal arguments, but they can also be associated with larger constituents. For instance, in the primed examples in (144), the contrastive foci consist of the verbal projections, and the focus particles are therefore associated with these VPs.

| a. | Jan | heeft | het boek | gekocht. | |

| Jan | has | the book | bought |

| a'. | Ja, | en | hij | is ook [VP | naar de | geweest]. | expansion | |

| yes | and | he | is also | to the cinema | been | |||

| 'Yes, and he has also been to the cinema.' | ||||||||

| b. | Jan | heeft | het boek | gekocht | en | is naar de bioscoop | geweest. | |

| Jan | has | the book | bought | and | is to the cinema | been |

| b'. | Nee, | hij | heeft | alleen [VP | het | gekocht]. | restriction | |

| no | he | has | only | the book | bought |

| c. | Heeft | Jan het boek | gekocht | of is hij | naar de bioscoop | geweest? | |

| has | Jan the book | bought | or is he | to the cinema | been |

| c'. | Hij | heeft [VP | het | gekocht]. | selection | |

| he | has | the book | bought |

More special cases are the focus particles zelfseven and slechtsmerely, which are not mentioned in Dik (1997), perhaps because they are not necessarily counter-presuppositional. These particles are often similar to the particles ookalso and alleenonly, but in addition they express a subjective evaluation, an extremely high degree, surprise, etc. The response in (145b) expresses that Peter’s presence was not expected, or rather, that his absence was expected.

| a. | Er | waren | veel mensen | aanwezig. | |

| there | were | many people | present | ||

| 'Many people were present.' | |||||

| b. | Ja, | ik | heb | zelfs | gezien. | |

| yes | I | have | even Peter | seen | ||

| 'Yes, I have even seen Peter.' | ||||||

Much more can be said about the meaning of focus particles, but we will not digress on this here; cf. König (1991), Foolen (1993), Barbiers, (1995a), and Van der Wouden (2002) for more discussion.

For the following discussion, it is crucial to realize that a focus particle and the contrastively focused phrase associated with it can form a constituent (although we will see that they can sometimes also be split). This is clear from the fact that they can occupy the clause-initial position together, as shown in (146) for the relevant examples in (142), (143), and (145). Note that it is not easy to construct similar cases for the examples in (144) with a contrastively focused VP: cf. ??Alleen het boek gekocht heeft hij.

| a. | Niet het | heeft | Jan gekocht, | maar | de . | |

| not the book | has | Jan bought | but | the record | ||

| 'Jan has not bought the book, but the record.' | ||||||

| b. | Ook/Alleen | de | heeft | Jan gekocht. | |

| also/only | the record | has | Jan bought | ||

| 'Jan has also/only bought the record.' | |||||

| c. | Zelfs | heb | ik | gezien. | |

| even Peter | have | I | seen | ||

| 'I have even seen Peter.' | |||||

Now that we have established that focus particles can form a constituent with contrastively focused phrases, we can discuss the hypothesis that focus movement is required to assign scope to the contrastively focused phrase. The examples in (147) show that while prepositional objects normally follow sentence negation, they can precede negation when they are contrastively focused. Since we have seen that focus movement targets a position that precedes sentence negation, the fact that the contrastively focused PP in (147b) can follow niet is a possible problem for the hypothesis that focus movement is obligatory.

| a. | Jan | wil | <*naar ʼm> | niet <naar ʼm> | luisteren. | |

| Jan | wants | to him | not | listen | ||

| 'Jan doesn't want to listen to him.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan | wil | <naar > | niet <naar > | wil | luisteren. | |

| Jan | wants | to him | not | wants | listen | ||

| 'Jan doesn't want to listen to him.' | |||||||

In (148) we provide similar focus constructions as in (147b), but now with a focus particle present. If such particles can indeed form a constituent with the contrastively focused PP, and if focus movement is obligatory, we correctly predict that the presence of these focus particles requires the prepositional object to be moved across the negation.

| a. | Jan wil | <alleen naar > | niet <*alleen naar > | luisteren. | |

| Jan wants | only to him | not | listen | ||

| 'Jan doesn't want to listen to him only.' | |||||

| b. | Jan wil | <ook naar > | niet <*ook naar > | luisteren. | |

| Jan wants | also to him | not | listen | ||

| 'Jan doesn't want to listen to him either.' | |||||

| c. | Jan wil | <zelfs naar > | niet <*zelfs naar > | luisteren. | |

| Jan wants | even to him | not | listen | ||

| 'Jan doesn't want to listen even to him.' | |||||

The examples in (148) thus support the claim that focus movement is obligatory. Similar examples, in which the contrastively focused PP is embedded in an adjectival complementive, are given in (149). The fact that the PPs must precede the adjective when they are accompanied by a focus particle again shows that focus movement is obligatory; cf. Barbiers (2014).

| a. | dat | Jan | <(alleen) | op > | boos <(*alleen) op > | is. | |

| that | Jan | only | with him | angry | is | ||

| 'that Jan is only angry with him.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | Jan | <(ook) | op > | boos <(*ook) op > | is. | |

| that | Jan | also | with him | angry | is | ||

| 'that Jan is also angry with him.' | |||||||

| c. | dat | Jan | <(zelfs) | op > | boos <(*zelfs) op > | is. | |

| that | Jan | even | with him | angry | is | ||

| 'that Jan is even angry with him.' | |||||||

The examples in (148) and (149) thus strongly suggest that the optionality of the focus movement in examples such as (147b) is only apparent: niet functions not as a sentence negation but as a constituent negation when the contrastively focused phrase follows it, i.e. we are dealing with the counter-presuppositional focus phrase niet op hem, which occupies the specifier of FocP as a whole.

The examples in (150) show that the examples in (148) and (149) alternate with constructions in which the designated focus position is not occupied by the whole contrastively focused phrase, but only by the focus particle; cf. Hoeksema (1989).

| a. | Jan | wil | alleen/ook/zelfs | niet | naar | luisteren. | |

| Jan | wants | only/also/even | not | to him | listen | ||

| 'Jan doesn't want to listen to him only/to him either/even to him.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | Jan | alleen/ook/zelfs | boos | <op > | is. | |

| that | Jan | only/also/even | angry | with him | is | ||

| 'that Jan is angry with him only/with him as well/even with him.' | |||||||

Usually both orders are possible, except when the focus particle is associated with a complement clause: as usual, such clauses are placed after the clause-final verbs. We illustrate this in (151a-b) with the focus particles alleen, but similar examples can be constructed for the other focus particles; example (151c) is added to show that the focus particle and the clause do form a constituent.

| a. | Jan heeft | alleen | gemeld | [ | hij | niet | zou | komen], | niet . | |

| Jan has | only | reported | that | he | not | would | come | not why | ||

| 'Jan has only reported that he would not come, not why.' | ||||||||||

| b. | ?? | Jan heeft alleen [ hij niet zou komen] gemeld. |

| c. | Alleen hij niet zou komen heeft hij gemeld. |

Barbiers (2010) has proposed that examples such as (150b) are derived by subextraction of the focus particle from the contrastively focused phrase, as in (152a); if this is correct, we can fully maintain the hypothesis that focus movement is obligatory. An alternative hypothesis would be that the focus particle is base-generated in the specifier of FocP as a scope marker (analogous to English constructions such as John hasn’t seen anybody, where the specifier of NegP is filled by the negative adverb not and the object appears in its regular position as a negative polarity item). If this proposal is correct, we need to revise the hypothesis that focus movement is obligatory by stating that the specifier position of FocP must be filled either by a moved focused phrase or by a focus particle with a contrastively focused phrase in its scope.

| a. | ... [FocP PRTi Foc ... [LD .. [ti PPA-accent]] ...] | movement analysis |

| b. | ... [FocP PRT Foc ... [LD ... [PPA-accent]] ...] | base-generation analysis |

It is not easy to distinguish between the two hypotheses. Barbiers supports the movement analysis by claiming that the focus particle can be moved further into the clause-initial position; this is demonstrated with ook, but the result seems to deteriorate with the particles alleen and zelfs, as shown in example (153).

| a. | Ook | is | Jan | [boos | op ]. | |

| also | is | Jan | angry | with him | ||

| 'Jan is also angry with him.' | ||||||

| b. | ?? | Alleen/?Zelfs | is | Jan | [boos | op ]. |

| only/even | is | Jan | angry | with him |

It is less clear what the base-generation hypothesis predicts. If the comparison with not in negative clauses such as John has not seen anybody is taken seriously, we would expect the focus particle to remain in its scope position because the adverb/particle not/niet in negative/contrastive focus constructions is not usually found in clause-initial position; this is shown in (154).

| a. | * | Niet | is Jan boos. | sentence negation |

| not | is Jan angry | |||

| Intended meaning: 'Jan is not angry.' | ||||

| b. | * | Niet | is | Jan | [boos | op ]. | counter-presuppositional focus |

| not | is | Jan | angry | with him | |||

| 'Jan is not angry with him.' | |||||||

The examples in (155a&b) show that we find similar judgments when we move the contrastively focused PP across the (presumed) focus particle; example (155b) is only acceptable when the preposed PP is assigned a B-accent, i.e. when it functions as a contrastive topic, but in this case the adjective would normally be contrastively focused: cf. Op hem is Jan alleen/zelfs boos. The same seems to be true for (155c): cf. Op hem is Jan niet boos (maar woedend) At him Jan is not angry (but furious).

| a. | Op i | is Jan | ook | [boos ti]. | |

| with him | is Jan | also | angry |

| b. | ?? | Op i | is Jan | alleen/zelfs | [boos ti]. |

| with him | is Jan | also/only/even | angry |

| c. | ?? | Op i | is Jan niet | [boos ti]. |

| with him | is Jan not | angry |

The above examples suggest that ook is not necessarily interpreted as a focus particle; in the (a)-examples in (153) and (155) it has an independent function, i.e. it is not associated with the PP. This is supported by the intransitive examples in (156): ook, zelfs and alleen are clearly focus particles when they immediately precede the contrastively focused phrase, as in the primed examples; an interpretation as a focus particle is much harder to get in the primeless examples, which is especially clear for alleen in (156c), where it is interpreted not as “only” but as “alone”.

| a. | Jan komt ook. | |

| Jan comes too |

| a'. | Ook Jan komt. | |

| Also Jan comes |

| b. | ?? | Jan komt zelfs. |

| Jan comes even |

| b'. | Zelfs Jan | komt. | |

| even Jan | comes |

| c. | # | Jan komt alleen. |

| Jan comes only |

| c'. | Alleen Jan komt. | |

| Only Jan comes |

The above discussion has shown that the argument in favor of the movement approach in (152a) based on the behavior of ook does not carry over to the other focus particles, while the base-generation approach seems to make a number of correct predictions about the examples in (153) through (156), provided we assume that ook can also be used with a syntactic function other than focus particle. Another argument in favor of the base-generation approach is that focused constituents can be embedded in islands for movement; cf. Hoeksema (1989:117-8). For instance, example (157b) shows that the wh-phrase op wie cannot be extracted from an embedded yes/no question, and (157c) shows that the same is true for the focused phrase alleen op Peter. This makes it unlikely that (157c') is derived by extracting the focus particle alleen from the embedded clause, and seems to refute the movement approach.

| a. | Marie vroeg [of | Jan boos | op Peter | is]. | |

| Marie asked whether | Jan angry | with Peter | is |

| b. | * | Op wiei | vroeg | Marie | [of | Jan boos ti | is]. |

| at who | asked | Marie | whether | Jan angry | is |

| c. | * | Marie vroeg alleen op | [of | Jan boos ti | is]. |

| Marie asked only with Peter | whether | Jan angry | is |

| c'. | Marie vroeg | alleen | [of | Jan boos | op | is]. | |

| Marie asked | only | whether | Jan angry | with Peter | is |

Example (157c') is consistent with the base-generation analysis in (152b): the focus particle alleen can be base-generated in the specifier of FocP of the matrix clause, since this results in a configuration in which this particle has the contrastively focused phrase op Peter in its a c-command domain. We tentatively conclude that the base-generation approach is superior to the movement approach.

Scalar focus particles like pasjust, alalready, nogstill, and maaronly must be associated with phrases that denote a linearly ordered scale. The focused phrase is typically a noun phrase containing a numeral or quantifier, as shown in (158). The numeral/quantifier selects a particular value from a contextually defined numerical scale (e.g. from one to twenty), and the particles qualify the part of the scale covered: maaronly indicates that this part is smaller than anticipated, while alalready indicates that this part is larger than anticipated. The fact that the particle and the focused phrase can be placed together in the main-clause initial position shows that they form a constituent.

| a. | We | hebben | maar / boeken | gelezen. | |

| we | have | only three/few books | read | ||

| 'We have read only three/a few books.' | |||||

| a'. | Maar | / boeken | hebben | we gelezen. | |

| only | three/few books | have | we read |

| b. | Hij | heeft | al / boeken | gelezen. | |

| he | has | already ten/many books | read | ||

| 'He has read ten/many books already.' | |||||

| b'. | Al / boeken | heeft | hij | gelezen. | |

| already ten/many books | has | he | read |

In example (159a), the particles nogstill and alalready function as temporal adverbial modifiers of the eventuality denoted by Jan werken: the eventuality lasts longer or starts earlier than one might have expected. In example (159b), the particles alalready and pasjust function as adverbial modifiers qualifying the distance between speech time and the start of the eventuality: they characterize the time span as respectively longer and shorter than one might have expected. The adverbial use of the particle maar is restricted to non-stative verbs and expresses durative aspect: Jan praat maarJan talks on and on. Although Barbiers (1995a: §3) has shown that these temporal uses also involve a modification of a linearly ordered scale (the time axis), we will ignore such cases in the following discussion.

| a. | Jan werkt nog/al. | |

| Jan works still/already | ||

| 'Jan is still/already working.' |

| b. | Jan werkt | hier | al/pas | sinds februari | |

| Jan works | here | already/just | since February | ||

| 'Jan has been working here since February already/only since February.' | |||||

The scalar focus particles in (158) modify nominal arguments, but the (a)-examples in (160) show that they can also modify noun phrases embedded in a PP. The (b)-examples further show that it is also possible for such particles to modify the PP as a whole, with apparently the same meaning. The fact that in all these examples the PP must precede the adjective geïnteresseerdinterested, by which it is selected, shows that focus movement is obligatory in these cases.

| a. | dat | Jan | <in maar ding> | geïnteresseerd <*in maar ding> | is. | |

| that | Jan | in only one thing | interested | is | ||

| 'that Jan is interested in only one thing.' | ||||||

| a'. | In maar ding | is Jan geïnteresseerd. | |

| in only one thing | is Jan interested |

| b. | dat | Jan | < maar in ding> | geïnteresseerd <* maar in ding> | is. | |

| that | Jan | only in one thing | interested | is | ||

| 'that Jan is interested in only one thing.' | ||||||

| b'. | Maar in ding | is Jan geïnteresseerd.’ | |

| only in one thing | is Jan interested |

That focus movement is obligatory is illustrated for direct objects in (161): while the definite noun phrase het boekthe book can easily follow the manner adverb zorgvuldig in (161a), the phrase modified by al must precede it.

| a. | Hij | heeft | <de boeken> | nauwkeurig <de boeken> | gelezen. | |

| he | has | the books | meticulously | read | ||

| 'He has read the books meticulously.' | ||||||

| b. | Hij | heeft | <al boeken> | nauwkeurig <*al boeken> | gelezen. | |

| he | has | already ten books | meticulously | read | ||

| 'He has meticulously read ten books already.' | ||||||

Counter-presuppositional and scalar focus particles are similar in that they both trigger focus movement. However, they cannot be considered as belonging to a single category because they behave differently in other respects (although we will see that the judgments on the relevant data are sometimes not very clear).

First, the examples in (162) show that the scalar focus particles differ from the counter-presuppositional ones in that they are preferably adjacent to the focused phrase; cf. the examples in (150). Although examples like the primed ones in (162) are considered perfectly acceptable in Barbiers (2010), we have given them a percentage sign because a Google search (July 25, 2025) on the strings [maar in één ding geïnteresseerd is] and [maar geïnteresseerd in één ding is] revealed that, after omitting linguistic sources, only the former can be found on the internet (29 hits), although there were also 4 cases with the PP is extraposed position ([maar geïnteresseerd is in één ding]). The search results for the strings with the finite verb is preceding maar (i.e. in the verb-second position), as in [is maar in één ding geïnteresseerd] and [is maar geïnteresseerd in één ding], show the same thing: there were 71 hits for the first string and 4 hits for the second string (which can be analyzed as involving string-vacuous extraposition).

| a. | Hij | heeft | al boeken | nauwkeurig | gelezen. | |

| he | has | already ten books | meticulously | read |

| a'. | % | Hij | heeft | al | nauwkeurig | boeken | gelezen. |

| he | has | already | meticulously | ten books | read |

| b. | dat | Jan maar in ding | geïnteresseerd | is. | |

| that | Jan only in one thing | interested | is |

| b'. | % | dat | Jan maar | geïnteresseerd | in ding | is. |

| that | Jan only | interested | in one thing | is |

Second, the examples in (163) show that the scalar focus particles in (162) can more easily follow their associated focus phrase than the counter-presuppositional particles in (153)/(155). Note, however, that our Google search shows that this word order is not common: the search string [maar in één ding geïnteresseerd] yielded more than two hundred hits (where we stopped counting), while the strings [in één ding maar geïnteresseerd] and [in één ding * maar geïnteresseerd] yielded no relevant results.

| a. | % | We | hebben | / boeken | maar | gelezen. |

| we | have | three/few books | only | read |

| a'. | / boeken | hebben | we | maar | gelezen. | |

| three/few books | have | we | only | read | ||

| 'We have read three books only/only a few books.' | ||||||

| b. | % | Jan | is | in ding | maar | geïnteresseerd. |

| Jan | is | in one thing | only | interested |

| b'. | In ding | is Jan maar | geïnteresseerd.’ | |

| in one thing | is Jan only | interested | ||

| 'Jan is interested in only one thing.' | ||||

Note in passing that the fact that scalar focus particles can either precede or follow their associated focus phrase can lead to ambiguity. Example (164) gives slightly adapted examples from Barbiers (1995a:70); the intended interpretation is indicated by underlining.

| a. | Jan heeft | meisje | pas | boeken] | gegeven. | |

| Jan has | one girl | just | two books | given | ||

| 'Jan has given one girl just two books.' | ||||||

| b. | % | Jan heeft | meisje | pas | boeken | gegeven. |

| Jan has | one girl | just | two books | given | ||

| 'Jan has given just one girl two books.' | ||||||

Third, although (163b') suggests that scalar focus particles can be stranded in the middle field of the clause, the examples in (165) show that they cannot be topicalized by themselves; the results are clearly more degraded than the comparable examples with counter-presuppositional focus particles in (153).

| a. | * | Maar | hebben | we / boeken | gelezen. |

| only | have | we three/few books | read |

| b. | * | Maar | is Jan in ding | geïnteresseerd. |

| only | is Jan in one thing | interested |

| c. | * | Al | heeft | hij | / boeken | gelezen. |

| already | has | he | ten/many books | read |

Barbiers (2010/2014) has shown that scalar and counter-presuppositional focus particles also differ in that the former can be doubled in certain varieties of Dutch, whereas the latter cannot. This contrast is illustrated by the examples in (166): we used the stative verb kennento know to rule out a temporal reading of the second occurrence of maar, which only occurs with dynamic verbs. The percentage sign in the (b)-examples indicates that at least some speakers of the standard variety do not (easily) accept the doubling of scalar focus particles.

| a. | Alleen/ook | ken | ik | (*alleen/*ook). | counter-presuppositional | ||

| only/also | Jan | know | I | only/also | |||

| 'I only/also know Jan.' | |||||||

| b. | Maar schrijver | ken | ik (%maar). | scalar | |

| only one writer | know | I | |||

| 'I know only one writer.' | |||||

| b'. | Al boeken | heeft | hij | (%al). | scalar | |

| already ten books | has | he | already | |||

| 'He has ten books already.' | ||||||

Barbiers also observes that counter-presuppositional and scalar focus particles sometimes co-occur (with a slight difference in meaning in the case of ook ... al). The examples in (167) show that in such cases the former precedes the latter. The diacritics in the (b)-examples indicate that some speakers of the standard variety may find these examples somewhat marked.

| a. | Jan is ook op | al | boos | geweest. | |

| Jan is also with Marie | already | angry | been | ||

| 'Jan has also been angry with Marie already.' | |||||

| a'. | Ook op | is Jan al | boos | geweest. | |

| also with Marie | is Jan already | angry | been |

| b. | (?) | Jan | is alleen | op | maar | boos | geweest. |

| Jan | is only | with Marie | only | angry | been | ||

| 'Jan has only been angry with Marie.' | |||||||

| b'. | (?) | Alleen op | is Jan maar | boos | geweest. |

| only with Marie | is Jan only | angry | been |

The examples in (168) show that counter-presuppositional focus particles can also occur in front of the scalar focus particle, with the contrastively focused phrase in its base position; it seems that the counter-presuppositional and scalar focus particles must then be adjacent and be placed in the middle field of the clause.

| a. | Jan is ook | al | boos op | geweest. | |

| Jan is also | already | angry with Marie | been |

| a'. | ? | Ook | is Jan al | boos op | geweest. |

| also | is Jan already | angry with Marie | been |

| a''. | * | Ook | al | is Jan | boos op | geweest. |

| also | already | is Jan | angry with Marie | been |

| b. | Jan | is alleen | maar | boos op | geweest. | |

| Jan | is only | only | angry with Marie | been |

| b'. | ?? | Alleen | is Jan maar | boos op | geweest. |

| only | is Jan only | angry with Marie | been |

| b''. | * | Alleen | maar | is Jan boos op | geweest. |

| only | only | is Jan angry with Marie | been |

Barbiers accounts for the data in (167) by assuming that scalar but not counter-presuppositional focus particles can be the head of a functional projection, which we take to be FocP. The primeless examples in (167) can now be derived by moving the contrastively focused phrase into the specifier of FocP, as indicated in (169a), while the primed examples can be derived from this structure by subsequent topicalization of the contrastively focused phrase. The primeless examples in (168) can be derived by placing the counter-presuppositional focus particle into the specifier position of FocP; we follow the earlier conclusion that the focus particle is base-generated as a scope marker in the specifier of FocP; cf. the discussion of (152). The fact that the singly-primed examples in (168) are marked may be due to the fact that these particles are not content-rich enough to undergo topicalization. The fact that the doubly-primed examples are highly degraded follows from the fact that ook al and alleen maar do not form a constituent.

| a. | Jan is ... [FocP [ook/alleen op Marie]i [[Foc al/maar] [LD [AP boos ti] geweest]]]. |

| b. | Jan is ... [FocP ook/alleen [[Foc al/maar] [LD [AP boos op Marie] geweest]]]. |

If scalar focus particles do not only occur as the head of FocP, but can also be used to modify a contrastively focused phrase, the doubling of such particles can be derived in a similar way as in (169a); cf. (170a). Since the head of FocP can remain phonetically empty and scalar focus particles are not obligatory, the cases without doubling can be analyzed as in (170b&c); of course, contrastive focus constructions without any focus particle have the structure in (170d).

| a. | % | Jan is [FocP [maar op jongen]i [[Foc maar] [LD [AP boos ti] geweest]]]. |

| b. | Jan is [FocP [maar op jongen]i [[Foc Ø] [LD [AP boos ti] geweest]]]. |

| c. | Jan is [FocP [op jongen]i [[Foc maar] [LD [AP boos ti] geweest]]]. |

| d. | Jan is [FocP [op jongen]i [[Foc Ø] [LD [AP boos ti] geweest]]]. |

Recall from the discussion of (162) that there are reasons to assume that scalar focus particles cannot occur in the specifier of FocP, which would be supported by the fact that they cannot occur in structures such as (169b). This restriction would follow immediately if we assume that scalar focus particles are not phrasal in nature, and specifier positions can only be filled by maximal projections.

The claim that scalar focus particles can function as the head of FocP may also explain the contrast between the two primeless examples in (171). Barbiers (1995a:84-5) noted that while the particle maar cannot be interpreted as a modifier of the direct object twee vogels of the embedded clause in (171a), this is possible in (171b), where the direct object is extracted from the embedded clause by topicalization. This follows from the analysis discussed above, according to which the specifier of FocP must be filled in order to assign scope to the contrastively focused phrase; example (171a) is unacceptable in the intended reading because the object has not undergone long focus movement, while (171b) is acceptable in this reading on the assumption that long focus movement precedes topicalization.

| a. | # | Jan zei | maar | dat | hij | vogels | gezien | had. |

| Jan said | only | that | he | two birds | seen | had |

| a'. | Jan zei [FocP ... maar [LD tsaid [CP dat hij vogels gezien had]]]. |

| b. | vogels | zei | Jan | maar | [dat | hij | gezien | had]]. | |

| two birds | said | Jan | only | that | he | seen | had | ||

| 'Jan said that he had seen only two birds.' | |||||||||

| b'. | [ vogels]i zei Jan [FocP t'i maar [LD tsaid [CP dat hij ti gezien had]]]. |

The examples discussed in this subsection suggest that scalar and counter-presuppositional focus particles have a different syntactic status: while the latter are arguably heads in all their manifestations, the former show a more projection-like behavior. We will leave this to future research and refer the reader to Barbiers (2014) and Bayer (2019/2023) for more detailed discussion of particle doubling.