- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Section 31.2 has shown that attributively used adjectives can be either verbal or truly adjectival in nature. This section adopts as its starting point the hypothesis that only participles of the latter type can be used as complementives: Subsection I examines this for the past/passive participles and Subsection II for the present participles. Subsection III concludes with a discussion of the complementive use of modal infinitives.

This subsection discusses the complementive use of past/passive participles. Section 31.2 has shown that past/passive participles like geslachtslaughtered and getrouwdmarried can be used as truly adjectival attributive participles, whereas past/passive participles like ingediendsubmitted and gevallenfallen cannot; cf. the tests listed in Table 6 and the discussion of (70) and (71). Consequently, if only truly adjectival participles can be used as complementives, we expect only the former to be possible in copular constructions. As we have seen in (72), repeated here as (106), this expectation comes true.

| a. | De schapen | bleken | geslacht. | |

| the sheep | turned.out | slaughtered | ||

| 'The sheep turned out (to be) slaughtered.' | ||||

| b. | Dat stel | bleek | getrouwd. | |

| that couple | turned.out | married | ||

| 'That couple turned out (to be) married.' | ||||

| c. | ?? | De aanvraag | bleek | ingediend. |

| the application | turned.out | prt.‑submitted |

| d. | ?? | De jongen | bleek | gevallen. |

| the boy | turned.out | fallen |

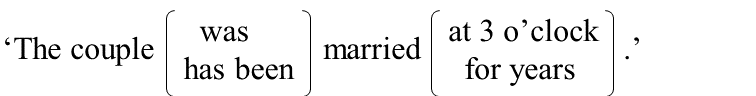

The participles geslacht and getrouwd in the constructions in (106a&b) also exhibit truly adjectival behavior with respect to the tests in Table 6. For example, the participle getrouwd has no aspectual content, but refers to the state of being married. Furthermore, (107a) shows that it can be prefixed with the negative marker on-, and (107b) that it can only be modified by time adverbs referring to an interval on the time axis, such as jarenlangfor years.

| a. | Het stel | bleek | ongetrouwd. | |

| the couple | turned.out | unmarried | ||

| 'The couple turned out to be unmarried.' | ||||

| b. | Het stel | bleek | jarenlang/??om drie uur | getrouwd. | |

| the couple | turned.out | for.years/at 3 o’clock | married | ||

| 'The couple turned out to have been married for years.' | |||||

The two remaining tests in Table 6 cannot be used for independent reasons: the verb trouwento marry has only one argument (a theme-subject), and comparative formation is impossible because the truly adjectival participle getrouwd is not scalar; one is either married or not. Since examples like (106a&b) exhibit truly adjectival behavior, they are sometimes called adjectival passives.

The remainder of this subsection will focus on the verb types of past/passive participles that can be used as complementives. Section 31.2.2 has shown that past/passive participles of intransitive verbs and nom-dat verbs that select the auxiliary hebben cannot be used attributively. The examples in (108) show that the same thing holds for the complementive use of these participles.

| a. | * | De jongen | is | gehuild. | is = copular |

| the boy | is | cried |

| b. | * | De moed | is | (ons) | ontbroken. | is = copular |

| the courage | has | us | lacked |

The following subsections will therefore focus on past/past participles that can also be used attributively and will also discuss a number of tests that can be used to distinguish this complementive use of these participles from their use in perfect-tense and passive constructions.

Since the copular verb zijnto be is homophonous with the passive auxiliary zijnto have been as well as with the auxiliary of time zijn selected by some unaccusative verbs, copular constructions with adjectival past/participle participles are sometimes difficult to distinguish from perfect-tense and passive constructions. The following subsections consider some tests that can be used to distinguish between them.

In the copular constructions in (106), the copular verb blijkento turn out is used instead of zijnto be in order to avoid problems arising from the fact that the copular verb zijnto be is homophonous with the perfect and passive auxiliaries zijn; if we replace blijken in (106b-d) by zijn, as in (109), it is not immediately clear whether we are dealing with a copular or a passive/past perfect construction. Note that we can leave (106a) aside for the moment, because transitive verbs do not take the perfect auxiliary zijnto be, but hebbento have; cf. Subsection 2.

| a. | Het stel | is getrouwd. | |

| that couple | is married | ||

| Past perfect construction: 'The couple has married.' | |||

| Copular construction: 'The couple is married.' | |||

| b. | De aanvraag | is ingediend. | |

| the application | is prt.‑submitted | ||

| Passive construction: 'The application has been submitted.' | |||

| c. | De jongen | is gevallen. | |

| the boy | is fallen | ||

| Past perfect construction: 'The boy has fallen.' | |||

Example (109c), unlike (106d), is perfectly acceptable, but it is not a copular construction, since the participle can only refer to the process of falling, not to the state of being fallen. This is also clear from the fact, illustrated in (110), that adverbials like al jarenlang cannot be used. From this we conclude that we are dealing with the perfect auxiliary zijn.

| De jongen | is gisteren/*al jarenlang | gevallen. | ||

| the boy | is yesterday/for years | fallen | ||

| 'The boy fell yesterday.' | ||||

We are not dealing with a copular construction in (109b) either: the participle does not refer to the state of being submitted, and (111a) shows that modification by the adverbial phrase al jarenlang is impossible. Moreover, an indirect object can be added, which would be impossible if the participle were truly adjectival; cf. Table 6. Since a passive door-phrase is also possible in (111a), we are clearly dealing with a passive construction. Recall that when the passive auxiliary is worden, as in (111b), an inchoative and/or iterative aspect is added, which makes the adverbial test inconclusive: adverbial phrases referring to an interval on the time axis become possible in this case.

| a. | De aanvraag | is gisteren/*al jarenlang | (door hem) | ingediend. | |

| the application | is yesterday/for years | by him | prt.-submitted | ||

| 'The application was submitted yesterday.' | |||||

| b. | De aanvraag | wordt | morgen/al jarenlang | ingediend. | |

| the application | is | tomorrow/for years | prt.-submitted | ||

| 'The application will be/has been submitted tomorrow/for years.' | |||||

In line with our findings on (109b&c), the participle getrouwdmarried in example (109a) can also have a verbal reading. Thus, (109a) differs from the unambiguous copular construction with blijkento turn out in (106b) in that it does not have to have the adjectival/state reading, but can also have the (verbal) past perfect reading. Accordingly, example (112a) shows that the adverbial phrases om drie uurat 3 oclock’ and al jarenlangfor years can both be used felicitously. However, this does not mean that constructions with zijn are always ambiguous: if the participle is prefixed with on-, as in (112b), we are clearly dealing with an adjective and only the stative reading is possible, as is also clear from the fact that the use of the adverbial PP om drie uur leads to unacceptability. Furthermore, example (112c) shows that the adjectival reading is excluded if the participle appears after the verb in clause-final position: this is, of course, in accordance with the finding from Section 28.2.2 that adjectival complementives must precede the clause-final verb(s); cf. also Table 2.

| a. | Het stel | is al jarenlang/om drie uur | getrouwd. | |

| the couple | is for years/at 3 o’clock | married |

|

| b. | Het stel | is al jarenlang/*om drie uur | ongetrouwd. | adjectival | |

| the couple | is for years/at 3 o’clock | unmarried | |||

| 'The couple has been unmarried for years.' | |||||

| c. | dat | het stel | om drie uur/*al jarenlang | is getrouwd. | verbal | |

| that | the couple | at 3 o’clock/for years | is married | |||

| 'that the couple was married at 3 oʼclock.' | ||||||

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the unacceptable version of sentences such as (112c) is sometimes produced. On closer inspection, most speakers will agree that this should be considered a performance error. The same error is occasionally made with pseudo-participles such as bekendwell-known/famous.

Section 28.2.1, sub IB, has shown that in Dutch dialects that allow possessive datives, the standard Dutch copular construction in (113a) alternates with the semi-copular construction in (113b).

| a. | Zijn band | is lek. | |

| his tire | is punctured |

| b. | Hij | heeft | de band | lek. | |

| he | has | the tire | punctured | ||

| 'He has a punctured tire.' | |||||

Now consider the standard Dutch example in (114a), which can be construed as either a passive or a copular construction, depending on whether the participle is construed as verbal or adjectival. The relevant reading can be established by several tests: the acceptability of adding the adverb gisterenyesterday to (114b) suggests that we are dealing with the verbal (passive) participle; this is confirmed by the fact that the passive door-phrase can also be added to such examples. The acceptability of adding adverbial phrases like al jarenlang to (114c) suggests that we are dealing with a copular construction; this is confirmed by the fact that the door-phrase cannot be used. Further evidence for these conclusions is that (114d) shows that the participle cannot follow zijn when the adverbial phrase is al jarenlang (with the same proviso as in (112c)).

| a. | Zijn fiets | is gestolen. | ||

| his bicycle | is stolen | |||

| Passive construction: 'His bike is stolen.' | is = passive auxiliary | |||

| Semi-copular construction: 'His bike is stolen.' | is = copula | |||

| b. | Zijn fiets | is gisteren | (door Peter) | gestolen. | |

| his bicycle | is yesterday | by Peter | stolen | ||

| 'His bicycle was stolen (by Peter) yesterday.' | |||||

| c. | Zijn fiets | is al jarenlang | (*door Peter) | gestolen. | |

| his bicycle | is for years | by Peter | stolen | ||

| 'His bicycle has been stolen for years.' | |||||

| d. | dat | zijn fiets | gisteren/*al jarenlang | is gestolen. | |

| that | his bicycle | yesterday/for years | is stolen | ||

| 'that his bicycle was stolen yesterday.' | |||||

In the non-standard varieties of Dutch that allow the semi-copular construction in (113b), (114a) can be translated as in (115a) on the truly adjectival reading of the participle. This sentence is again ambiguous, as it can also be interpreted as a perfect-tense construction. The construction can be disambiguated in a similar way as in (114a): the addition of the adverb gisteren in (115b) is only possible with a verbal reading of the participle, while the addition of al jarenlang in (115c) triggers the adjectival/state reading. As expected, the adverbial phrase al jarenlang cannot be used in the corresponding present-tense construction *Hij steelt al jarenlang de fiets (lit.: He steals the bike for years). Finally, example (114d) shows that the adverbial phrase al jarenlang yields a degraded result when the participle follows the auxiliary in clause-final position.

| a. | Hij | heeft | de fiets | gestolen. | |

| he | has | the bicycle | stolen | ||

| Past perfect construction: 'He has stolen the bike.' | |||||

| Semi-copular construction: 'His bike was stolen.' | |||||

| b. | Hij | heeft | gisteren | de fiets | gestolen. | |

| he | has | yesterday | the bicycle | stolen | ||

| 'He stole the bicycle yesterday.' | ||||||

| c. | Hij | heeft | al jarenlang | de fiets | gestolen. | |

| he | has | for years | the bicycle | stolen | ||

| 'He has had his bicycle stolen for years.' | ||||||

| d. | dat | hij | gisteren/*al jarenlang | de fiets | heeft | gestolen. | |

| that | he | yesterday/for years | the bicycle | has | stolen |

Since the participle can only be truly adjectival if the subject enters into a possessive relation with the object, leading to the interpretation “his bike”, (115a) can also be disambiguated by adding a possessive pronoun to the object: this blocks the possessive relation and consequently (116) is only compatible with a verbal reading of the participle.

| Hij | heeft | haar/zijn fiets | gestolen. | ||

| he | has | her/his bicycle | stolen | ||

| 'He has stolen her/his bicycle.' | |||||

Section 28.2.1, sub IB, has also shown that standard Dutch has a similar semi-copular construction with hebbento have, which occurs under somewhat stricter conditions than the dialect construction in (115a). A sentence like (117a), for example, is ambiguous between a past perfect and a semi-copular reading. That (117a) can be interpreted as a past perfect construction is shown by the fact that it has the present tense counterpart in (117b), and that it can be interpreted as a semi-copular construction is shown by the fact that hebben can be replaced by the semi-copular verb krijgento get in (117c). Note that, unlike the dialectal construction in (115a), the standard Dutch semi-copular construction is not inherently possessive, so it is also available when the object contains a possessive pronoun.

| a. | Jan heeft | zijn raam | niet | gesloten. | |

| Jan has | his window | not | closed | ||

| Past perfect construction: 'Jan has not closed his window.' | |||||

| Semi-copular construction: 'Jan does not have his window closed.' | |||||

| b. | Jan sluit | zijn raam | niet. | |

| Jan closes | his window | not |

| c. | Jan krijgt | zijn raam | niet | gesloten. | |

| Jan gets | his window | not | closed |

The semi-copular and past perfect readings in (117a) are again subject to the familiar restrictions: the use of punctual time adverbs such as gisteren, as in (118a), is only possible in the verbal/eventive reading of the participle, while the addition of non-punctual time adverbs such as altijd in (118b) triggers the adjectival/state reading. Placing the participle after the finite verb in clause-final position, as in (118c), is only possible in the perfect-tense construction, i.e. when the participle is verbal; this is clear from the fact that this construction is only compatible with punctual adverbial phrases like gisteren (although altijd is also compatible with a habitual/iterative interpretation of perfect-tense constructions, an option we have ignored here).

| a. | Jan heeft | gisteren | zijn raam | gesloten. | |

| Jan has | yesterday | his window | closed | ||

| 'Jan did not close his window yesterday.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | altijd | zijn raam | gesloten. | |

| Jan has | always | his window | closed | ||

| 'Jan always has his window closed.' | |||||

| c. | dat | Jan zijn raam | gisteren/*altijd | heeft | gesloten. | |

| that | Jan his window | yesterday/always | has | closed | ||

| 'that Jan did not close his window yesterday.' | ||||||

This subsection has shown that only truly adjectival participles can be used as predicates in (semi-)copular constructions. Sometimes there is ambiguity between the predicative and the passive/past perfect constructions, but we have shown that some of the tests from Section 31.1 can be used to distinguish between the two readings. It has also been shown that the relative position of the participle and the remaining verbs in clause-final position is relevant: if the participle follows the verb hebben/zijn, the adjectival reading is blocked.

Section 31.2.2 has shown that past participles of nom-dat verbs can be used attributively to modify a head noun corresponding to the theme-subject, provided that the verb takes the auxiliary zijn in the perfect tense. This is shown again in (119).

| a. | Die opmerking | is ons | opgevallen. | perfect auxiliary zijn | |

| that remark | is us | prt.-noticed | |||

| 'We have noticed that remark.' | |||||

| a'. | de | ons | opgevallen | opmerking | |

| the | us | prt.-noticed | remark | ||

| 'the remark we have noticed' | |||||

| b. | De moed | heeft | ons | ontbroken. | perfect auxiliary hebben | |

| the courage | has | us | lacked | |||

| 'We (have) lacked the courage.' | ||||||

| b'. | ?? | de | ons | ontbroken | moed |

| the | us | lacked | courage |

Since the past participle ontbroken cannot be used attributively, it is not surprising that it cannot be used predicatively; cf. (120b). However, example (120a) shows that the past participle of the nom-dat verb opvallento strike/attract attention cannot be used predicatively either. This is consistent with the conclusion drawn in 31.2.2, sub II, that past participles of nom-dat verbs like opvallen do not have a truly adjectival interpretation; cf. (64).

| a. | * | De opmerking | is/blijkt | opgevallen. | perfect auxiliary zijn |

| the remark | is/turns.out | prt.-noticed |

| b. | * | De moed | is/bleek | ontbroken. | perfect auxiliary hebben |

| the courage | is/turns.out | lacked |

For completeness’ sake, note that (119a) is not ambiguous between the perfect-tense and the copular construction, since truly adjectival participles generally do not allow nominal arguments (here the pronoun onsus). That (119a) cannot be a copular construction is also illustrated in (121): it only allows the addition of adverbs such as gisterenyesterday, which refer to a specific point on the time axis; cf. Table 6.

| Die opmerking | is ons | gisteren/*al jaren | opgevallen. | ||

| that remark | is us | yesterday/for years | prt.-noticed | ||

| 'We noticed that remark yesterday.' | |||||

As also shown in Section 31.2.2, past participles of object experiencer psych-verbs can be used attributively if the modified noun corresponds to the [+human] object of the active verb. This is illustrated once more in (122).

| a. | Die berichten | verontrusten | de jongen. | |

| those messages | disturb | the boy |

| a'. | de | verontruste | jongen | |

| the | disturbed | boy |

| b. | Het avontuur | wond | de jongen | op. | ||||

| the adventure | excited | the boy | prt. | |||||

| 'The adventure excited the boy.' | ||||||||

| b'. | de | opgewonden | jongen | |

| the | excited | boy |

The examples in (123) demonstrate that the past participles can also be used predicatively; in such cases there is no confusion with perfect-tense constructions, since these psych-verbs select the auxiliary hebbento have. Observe that the truly adjectival status of the participles is also evident from the fact that they can be modified by degree modifiers such as heel/zeervery.

| a. | De jongen | is al jaren/*gisteren | (heel) | verontrust | (over die berichten). | |

| the boy | is for years/yesterday | very | disturbed | about those messages |

| b. | De jongen | is al jaren/*gisteren | (zeer) | opgewonden | (over het avontuur). | |

| the boy | is for years/yesterday | very | excited | about the adventure |

This subsection has shown that the complementive use of past/passive participles is more restricted than their attributive use: it is only possible if the participle is truly adjectival, i.e. with a subset of transitive and monadic unaccusative verbs and object experiencer verbs; cf. Table 5.

Section 31.2.2, sub II, has shown that the truly adjectival reading of present participles is restricted to object experiencer psych-verbs. This implies that only the present participles of psych-verbs can occur in the copular construction. The following subsections will show that this expectation is more or less confirmed, although some caveats have to be made. Let us start with a brief overview.

Present participles of intransitive and transitive verbs cannot be used in copular constructions. This has already been seen in (83a&b), and some more examples are given in (124) and (125). The unacceptability of the predicative constructions in the primed examples contrasts sharply with the acceptability of the corresponding attributive constructions: cf. het vloekende/werkende meisjethe cursing/working girl and het zingende/etende meisjethe singing/eating girl.

| a. | Het meisje | vloekt. | |

| the girl | curses |

| a'. | * | Het meisje | is | vloekend. |

| the girl | iscopula | cursing |

| b. | Het meisje | werkt. | |

| the girl | works |

| b'. | * | Het meisje | is | werkend. |

| the girl | iscopula | working |

| a. | Het meisje | zingt | een lied. | |

| the girl | sings | a song |

| a'. | * | Het meisje | is | zingend. |

| the girl | iscopula | singing |

| b. | Het meisje | eet | een appel. | |

| the girl | eats | an apple |

| b'. | * | Het meisje | is | etend. |

| the girl | iscopula | eating |

However, the examples in (126) show that there are many metaphorically used present participles that can be used not only attributively but also predicatively. Since the meanings of these forms are highly specialized, we may be dealing with true adjectives. We added the (c) and (d)-examples to show that the corresponding non-metaphorically used present participles yield unacceptable results.

| a. | een | moordend | tempo | ||||

| a | killing | tempo | |||||

| 'a punishing tempo' | |||||||

| c. | een | moordende | scholier | ||||

| the | killing | student | |||||

| 'the student who is killing' | |||||||

| a'. | Het tempo is moordend. |

| c'. | * | De scholier is moordend. |

| b. | een | sprekende | gelijkenis | ||||

| a | speaking | resemblance | |||||

| 'a | |||||||

| remarkable/telling resemblance' | |||||||

| d. | de | sprekende | voorzitter | ||||

| the | speaking | chairman | |||||

| 'the chairman, who is speaking' | |||||||

| b'. | De gelijkenis is sprekend. |

| d'. | * | De voorzitter is sprekend. |

Example (83c) has already shown that present participles of unaccusative verbs cannot usually be used in copular constructions; further examples are given in (127). The unacceptability of the predicative constructions in the primed examples again contrasts sharply with the acceptability of the corresponding attributive constructions de vertrekkende gastenthe leaving guests and de vallende jongenthe falling boy.

| a. | De gasten | zijn | vertrokken. | |||

| the guests | are | left | ||||

| 'The guests have left.' | ||||||

| a'. | * | De gasten zijn | vertrekkend. |

| the guests arecopula | leaving |

| b. | De jongen | is gevallen. | ||||

| the boy | is fallen | |||||

| 'The boy fell/has fallen.' | ||||||

| b'. | * | De jongen | is | vallend. |

| the boy | iscopula | falling |

The primed examples in (128) provide some possible counterexamples to the claim that the complementive use of present participles of unaccusative verbs is excluded.

| a. | De man is gestorven. | ||||

| the man is died | |||||

| 'The man has died.' | |||||

| b. | Het schip | is gezonken. | |||

| the ship | is sunk | ||||

| 'The ship has sunk.' | |||||

| c. | Het verzet is gegroeid | ||||

| the resistance is grown | |||||

| 'The resistance has grown.' | |||||

| a'. | De man is stervende. | |

| the man is dying |

| b'. | Het schip is zinkende. | |

| the ship is sinking |

| c'. | Het verzet is groeiende. | |

| the resistance is growing |

| a''. | de stervende man | |

| the dying man |

| b''. | het zinkende schip | |

| the sinking ship |

| c''. | het groeiende verzet | |

| the growing resistance |

However, it is not clear whether these are really copular constructions. First, the present participles in the singly-primed examples have an -e ending, which is normally not possible with predicatively used adjectives. Second, they seem to refer to ongoing processes, just like the attributively used verbal present participles in the doubly-primed examples: the subject of the clause is said to be undergoing a change of state. This is clear from the fact that the primed examples can be paraphrased by a durative aan het + infinitive construction; example (128b'), for instance, is virtually synonymous with Het schip is aan het zinkenThe ship is sinking.

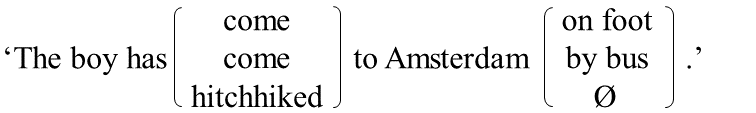

Other potentially problematic cases arise with motion verbs like lopento walk, bussento travel by bus and liftento hitchhike, which can be used either as intransitive or as unaccusative verbs; cf. Section V2.1.2, sub I. The unaccusative forms of these verbs in (129b) require the presence of a directional PP and select the perfect auxiliary zijnto be. The forms of these verbs in (129a) behave simply as intransitive verbs; they occur without a predicative complement and select the perfect auxiliary hebbento have. The examples in (129c) show that the present participle of these motion verbs can be used as a predicate in copular constructions.

| a. | De jongen | heeft | gelopen/gebust/gelift. | intransitive verb | |

| the boy | has | walked/bused/hitchhiked |

| b. | De jongen | is naar Amsterdam | gelopen/gebust/gelift. | unaccusative verb | |

| the boy | is to Amsterdam | walked/bused/hitchhiked |

|

| c. | De jongen | is/bleek | (*naar Amsterdam) | lopend/bussend/liftend. | |

| the boy | is/ turned.out | to Amsterdam | walking/busing/hitchhiking | ||

| 'The boy has/appeared to have come on foot/by bus/hitchhiking.' | |||||

The examples in (129c) differ from the singly-primed examples in (128) in that they do not refer to an ongoing event. A sentence like Ik ben lopend does not imply that the speaker is walking at the moment of utterance, but merely expresses that he has come on foot. This suggests that the present participles in (129c) are truly adjectival, which seems to be supported by the fact that the predicative PP-complement naar Amsterdam cannot be used, in contrast to what is the case with the attributively used verbal participles in de naar Amsterdam lopende jongenthe boy who is walking to Amsterdam.

Nom-dat verbs usually resist the formation of truly adjectival present participles, regardless of whether they select the auxiliary zijn or hebben in the perfect tense; cf. (130). Section 31.2.2, sub IIB, has already shown that the present participle of the verb opvallento strike/attract attention is an exception in this respect.

| a. | De maaltijd | is ons | goed | bevallen. | |

| the meal | is us | good | pleased | ||

| 'The meal (has) pleased us very much.' | |||||

| a'. | * | De maaltijd | is | (goed) | bevallend. | vs. de goed bevallende maaltijd |

| the meal | iscopula | good | pleasing |

| b. | De maaltijd | heeft | ons | goed | gesmaakt. | |

| the meal | has | us | good | tasted | ||

| 'We (have) enjoyed the meal very much.' | ||||||

| b'. | * | De maaltijd | is | (goed) | smakend. | vs. de goed smakende maaltijd |

| the meal | iscopula | good | tasting |

This leaves us with the present participles of the object experiencer psych-verbs. The primed examples in (131) show that these can be used comfortably as predicates in copular constructions. The present participles in the primed examples can be modified by degree modifiers like zeer/heelvery, which confirms that we are dealing with truly adjectival participles in these examples.

| a. | Het bericht | verontrust | mij. | |

| the message | disturbs | me |

| a'. | Het bericht | is (heel) | verontrustend. | |

| the message | is very | disturbing |

| b. | Het avontuur | wond | ons | op. | |

| the adventure | excited | us | prt. |

| b'. | Het avontuur | is (zeer) | opwindend. | |

| the adventure | is very | prt.-exciting |

| c. | Het boek | intrigeert | ons. | |

| the book | intrigues | us |

| c'. | Het boek | is (zeer) | intrigerend. | |

| the book | is very | intriguing |

The examples in (132) show that the result is occasionally unacceptable. When it is, the intended assertion can usually be expressed by a genuine adjective, suggesting that the adjectival use of the present participle is blocked by the availability of this alternative.

| a. | Die opmerkingen | irriteren | mij. | |

| those remarks | annoy | me |

| a'. | Die opmerkingen | zijn | erg irritant/??irriterend. | |

| those remarks | are | very annoying |

| b. | Het schilderij | bekoorde | mij. | |

| the painting | beguiled | me |

| b'. | Het schilderij | is erg bekoorlijk/*?bekorend. | |

| the painting | is very beguiling |

| c. | Het boek | interesseert | mij. | |

| the book | interests | me |

| c'. | Het boek | is erg interessant/*interesserend. | |

| the book | is very interesting |

This morphological “blocking” approach to the unacceptable versions of the primed examples in (132) can be supported by the fact that the present participles cannot be used attributively on their adjectival/state reading either; this reading can only be expressed by the genuine adjectives. Note in passing that the primeless examples in (133) show that the attributive use of the present participles on their verbal/eventive reading leads to different degrees of acceptability.

| a. | een irriterende opmerking | ||

| 'a remark that is annoying someone' | |||

| a'. | een irritante opmerking | ||

| 'an annoying remark' | |||

| b. | ? | een bekorend schilderij | |

| 'a painting that is beguiling someone' | |||

| b'. | een bekoorlijk schilderij | ||

| 'a charming painting' | |||

| c. | * | een interesserend boek |

| c'. | een interessant boek | ||

| 'an interesting book' | |||

The fact that the present participles in (132) cannot be used as complementives thus follows from the fact, illustrated in (133), that they are always verbal, if at all possible.

Table 7 summarizes the tendencies observed in the previous subsections. Occasionally, participles appear in copular constructions that are not expected on the basis of these tendencies, but these exceptions are mostly idiosyncratic in nature.

| intransitive verbs | *Het meisje is vloekend | (124a') |

| transitive verbs | *Het meisje is zingend | (125a') |

| unaccusative verbs possible exceptions: (i) present participles with -e (ii) motion verbs | *De gasten zijn vertrekkend Het schip is zinkende De jongen bleek lopend | (127a') (128b') (129c) |

| nom-dat verbs (i) with zijn as an auxiliary (ii) with hebben as an auxiliary | *De maaltijd is (goed) bevallend *De maaltijd is (goed) smakend | (130a') (130b') |

| object experiencer psych-verbs | Het avontuur is (erg) opwindend | (131b') |

This subsection discusses the predicative use of modal infinitives. We will show that this use differs from the attributive use of these elements in that it is compatible only with the ability reading. This restriction would follow from our more general claim that complementives are not verbal, since modal infinitives expressing obligation were shown to be verbal in Section 31.2.3. We conclude with a potential counterexample to the restriction that complementive modal infinitives must have an ability reading.

Apart from their attributive use, modal infinitives can also be used as predicates in copular and vinden-constructions. Predicatively used te-infinitives differ from attributively used ones, however, in that they only allow the ability reading; e.g. example (134a) does not easily allow an interpretation according to which the books must be read: the only readily available reading is that the books are easily accessible.

| a. | Deze boeken | zijn/leken | (gemakkelijk) | te lezen. | |

| these books | are/appeared | easily | to read | ||

| 'These books are easily accessible.' | |||||

| a'. | Jan vindt | de boeken | (gemakkelijk) | te lezen. | |

| Jan considers | the books | easily | to read | ||

| 'Jan believes that the books can be read easily.' | |||||

| b. | Deze afstand | is/leek | (gemakkelijk) | af | te leggen. | |

| this distance | is/appeared | easily | prt. | to cover | ||

| 'This distance can be covered easily.' | ||||||

| b''. | Jan vindt | de afstand | (gemakkelijk) | af te leggen. | |

| Jan considers | the distance | easily | to cover | ||

| 'Jan believes that the distance can be covered easily.' | |||||

The adjective gemakkelijk acts as an adverb modifying the te-infinitive and not as a predicative complement of the verb zijn/lijken. Since adverbs are not morphologically distinguished from other adjectives in Dutch, the examples in (134) are easily confused with the easy-to-please construction, which does involve a predicatively used adjective. Fortunately, there are several criteria for distinguishing the two constructions: (i) the predicatively used adjective is obligatory in the easy-to-please construction, whereas the adverbially used adjective can be dropped in the case of modal infinitives; (ii) the infinitival clause has an obligatory complementizer om in the easy-to-please construction, whereas this complementizer cannot co-occur with modal infinitives; (iii) in attributive constructions, the infinitival clause follows the modified noun, whereas the modal infinitive precedes it. These tests are discussed in more detail in Section 28.5, sub IV.

Section 31.2.3 has shown that the noun modified by attributively used modal infinitives corresponds to the accusative object in the matching active sentence. Something similar holds for predicatively used modal infinitives: the noun phrase they are predicated of also corresponds to the accusative object in the matching active sentence. This is clear from the contrast between the examples in (134) and (135): the modal infinitives in (134) are transitive and the result is fine, while the modal infinitives in (135) are intransitive and unaccusative, respectively, and the result is unacceptable.

| a. | * | Er | is | te lachen. |

| there | is | to laugh |

| b. | * | Er | is | te vallen. |

| there | is | to fall |

However, there are some problems that should be taken into account. First, it seems that in some cases the predicative use of transitive modal infinitives can be blocked by a competing construction, as illustrated in (136): we would expect the complementive modal infinitives te kopen/huren to be able to appear in these copular constructions with an ability reading, but this seems to be hampered by the possibility of using te koop/huurfor sale/rent.

| a. | Dit huis | is te koop/??kopen. | |

| this house | is to buy/buy | ||

| 'This house is for sale (i.e. can be bought).' | |||

| b. | Deze auto | is te huur/??huren. | |

| this car | is to rent/rent | ||

| 'This car is for rent (i.e. can be rented).' | |||

Second, examples like (137) have been put forward as counterexamples to the claim that intransitive verbs cannot act as modal infinitives. The fact that these examples have an ability reading makes it plausible that we are indeed dealing with modal infinitives. The difference between the examples in (135) and (137) is not clear to us. For the moment, we can only observe that the examples in (137) are special in that there is a certain preference for using the verb vallen instead of zijn, and that some adverbial or quantified phrase like niet or veel must be present.

| a. | Er | valt/?is | hier | niet | te werken. | |

| there | falls/is | here | not | to work | ||

| 'One cannot work here.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | valt/??is | hier | veel | te lachen. | |

| there | falls/is | here | much | to laugh | ||

| 'One can laugh a lot here.' | ||||||

We have seen in Section 31.2.3 that arguments and predicative complements of the verb can only be expressed in the attributive construction when the modal infinitive has a verbal (i.e. obligation) reading; cf. (99). The fact that arguments and predicative complements cannot occur if the modal infinitives are used as complementives thus supports our claim that they are always truly adjectival in this syntactic function.

| a. | *? | Deze brief | is aan de studenten | te sturen. |

| this letter | is to the students | to send |

| b. | *? | De boeken | zijn | in de kast | te zetten. |

| the books | are | in the cupboard | to put |

A potential problem for this claim, however, is that complementive modal infinitives can be combined with the predicative parts of collocations like schoon makento clean or kwaad/bang makento anger/frighten. This is shown in (139).

| a. | Dit fornuis | is gemakkelijk | schoon | te maken. | |

| this cooker | is easily | clean | to make | ||

| 'This cooker can be cleaned easily.' | |||||

| b. | Jan is gemakkelijk | kwaad/bang | te maken. | |

| Jan is easily | angry/afraid | to make | ||

| 'Jan can be made angry/afraid easily.' | ||||

A similar argument can be construed for the claim that predicatively used modal infinitives are always truly adjectival: this is based on the fact that the addition of a (passive) door-phrase leads to a marginal result, whereas the addition of a voor-phrase is fully acceptable when the adverb gemakkelijk is present. The percentage sign in (140a) indicates that our judgment is controversial, since similar examples have been given as acceptable in the literature. However, speakers who accept the door-phrase in (140a) report that the sentence has the ability reading, suggesting that the modal infinitive here is adjectival, not verbal.

| a. | % | Dit boek | is | door Peter | te lezen. |

| this book | is | by Peter | to read | ||

| 'This book must be read by Peter.' | |||||

| b. | Dit boek | is voor Peter | gemakkelijk | te lezen. | |

| this book | is for Peter | easily | to read | ||

| 'This book can easily be read by Peter.' | |||||

Another argument for assuming the nonverbal status of predicatively used modal infinitives is that for many (but not all) speakers they must precede the finite verb in clause-final position.

| a. | dat | deze boeken | (gemakkelijk) | te lezen | zijn/lijken. | |

| that | these books | easily | to read | are/appear |

| a'. | % | dat | deze boeken (gemakkelijk) zijn/lijken te lezen. |

| b. | dat | deze afstand | (gemakkelijk) | af | te leggen | is/lijkt. | |

| that | this distance | easily | prt. | to cover | is/appears |

| b'. | % | dat deze afstand (gemakkelijk) af is/lijkt te leggen. |

The fact that some speakers seem to allow the modal infinitives to follow the copular verbs in (141) is not conclusive for arguing that they are verbal, since postverbal placement of the modal infinitive is excluded for all speakers if there is more than one verb in clause-final position, as in (142).

| a. | dat | deze boeken | me | altijd | (gemakkelijk) | te lezen | hebben | geleken. | |

| that | these books | me | always | easily | to read | have | appeared |

| a'. | * | dat deze boeken me altijd (gemakkelijk) hebben geleken te lezen. |

| b. | dat | deze afstand | me altijd | (gemakkelijk) | af | te leggen | heeft | geleken. | |

| that | this distance | me always | easily | prt. | to cover | have | appeared |

| b'. | * | dat deze afstand me altijd (gemakkelijk) <af> heeft geleken <af> te leggen. |

On the other hand, the fact that modal infinitives can precede the verbs in clause-final position shows that they are not verbal; the examples in (143) show that unequivocally verbal te-infinitives never occupy this preverbal position.

| a. | * | dat | Jan deze boeken | te lezen | bleek. |

| that | Jan these books | to read | turned.out |

| a'. | dat Jan deze boeken bleek te lezen. |

| b. | * | dat | Jan deze afstand | af | te leggen | bleek. |

| that | Jan this distance | prt. | to cover | turned.out |

| b'. | dat Jan deze afstand af bleek te leggen. |

We conclude, therefore, that complementive modal infinitives are truly adjectival, and hypothesize that their postverbal placement in the examples in (141) results from a performance error comparable to that found with complementive past participles; cf. the discussion of (112c) in Subsection I.

Before concluding the discussion, we would like to point out a potential problem for our earlier claim that modal infinitives cannot be used in predicative position with an obligation reading. Consider the examples in (144), which allow for an obligation reading.

| a. | dat | Jan dat | te doen | heeft. | heeft can be replaced by krijgt | |

| that | Jan that | to do | has | |||

| 'that Jan has to do that.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan dat boek | te lezen | heeft. | heeft can be replaced by krijgt | |

| that | Jan that book | to read | has | |||

| 'that Jan has to read that book.' | ||||||

The fact that the infinitives precede the clause-final finite verb indicates that they are not verbal. This raises the question as to whether we are dealing with predicatively used modal infinitives in this construction. An affirmative answer to this question is suggested by the fact that the verb hebben can also be used in other predicative constructions, such as (145); note that hebben can be replaced by krijgento get, an option that is also available for the examples in (144).

| dat | Jan het raam | niet open | heeft. | heeft can be replaced by krijgt | ||

| that | Jan the window | not open | has |

To our knowledge, the question of whether we are dealing with predicatively used modal infinitives in (144) has not yet been investigated. There are two possible arguments against the assumption that we are dealing with modal infinitives in these constructions. The first argument, illustrated in (146), is that the te-infinitive can be predicated of a subject of a transitive verb in the hebben construction, while we have seen in (134) that modal infinitives are usually predicated of direct objects of transitive verbs in the copular construction.

| dat | Jan (mij) | te gehoorzamen | heeft. | heeft cannot be replaced by krijgt | ||

| that | Jan me | to obey | has | |||

| 'that Jan has to obey (me).' | ||||||

The second argument, illustrated in (147), is that the hebben construction occurs with intransitive and unaccusative verbs, whereas attributively or predicatively used modal infinitives of these verbs normally do not occur; cf. (93) and (135).

| a. | dat | Jan te werken | heeft. | heeft cannot be replaced by krijgt | |

| that | Jan to work | has | |||

| 'that Jan has to work.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Jan te komen | heeft. | heeft cannot be replaced by krijgt | |

| that | Jan to come | has | |||

| 'that Jan has to come.' | |||||

We leave it open here whether these two arguments are sufficient to refute the claim that we are dealing with modal infinitives in (144); the examples in (146) and (147) may be of a different nature than those in (144), given that hebben can only be replaced by the semi-copular krijgen in the first set of examples.