- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Circumpositional phrases are typically used in directional constructions, but many of these phrases can also be used in locational constructions. There is a notable difference between these two uses: while the second part of the circumposition is usually obligatory in directional constructions, it can often be omitted in locational constructions without affecting the core meaning of the sentence. This casts some doubt on the assumption that they are constructions of a similar status.

This subsection considers the circumpositions from Table 10 and Table 12 from Section 32.2.5 and investigates (i) whether they can be used in locational and/or directional constructions and (ii) whether the second part can be omitted. The results are summarized in Subsection II.

This subsection deals with the use of spatial circumpositions with aan as their second member. The examples in (277) show that the circumpositional phrase tegen de muur aan can indicate a (change of) location or a direction. Ignore the cases without aan; we will address them in a moment.

| a. | Er | stond | een ladder | tegen de muur | (aan). | location | |

| there | stood | a ladder | against the wall | aan | |||

| 'A ladder stood against the wall.' | |||||||

| a'. | Jan zette | een ladder | tegen de muur | (aan). | change of location | |

| Jan put | a ladder | against the wall | aan | |||

| 'Jan put a ladder against the wall.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan liep | tegen | de ladder | *?(aan). | direction | |

| Jan walked | against | the ladder | aan | |||

| 'Jan ran into the ladder.' | ||||||

The circumpositional phrase achter de optocht aan in (278) behaves differently in that it can only be used to indicate a direction.

| a. | De kinderen | liepen | achter | de optocht | (*aan). | location | |

| the children | walked | behind | the parade | aan |

| a'. | Jan plaatste | de kinderen | achter | de optocht | (*aan). | change of location | |

| Jan put | the children | behind | the parade | aan |

| b. | Er | liepen | veel kinderen | achter | de optocht | #(*aan). | direction | |

| there | walked | many children | behind | the parade | aan | |||

| 'Masses of children followed the parade.' | ||||||||

In the locational examples in (277a&a'), the element aan can be omitted without any significant change in meaning; the use of aan merely seems to emphasize that there is physical contact between the located object and the reference object. In the directional examples in (277b) and (278b), on the other hand, aan must be present; without it the construction is either degraded or acquires a locational meaning. This can be easily demonstrated for (278b) by considering its perfect-tense counterparts in (279): if the verb lopen takes the auxiliary zijn, it is a verb of traversing, which requires a directional complementive, and aan is obligatory; if the verb lopen takes the auxiliary hebben, it is an activity verb, which is compatible with a locational adverbial PP, and aan is preferably dropped.

| a. | Er | zijn | horden kinderen | achter | de optocht | *(aan) | gelopen. | |

| there | are | masses children | behind | the parade | aan | walked | ||

| 'Masses of children have followed the parade.' | ||||||||

| b. | Er | hebben | horden kinderen | achter | de optocht | (?aan) | gelopen. | |

| there | have | masses children | behind | the parade | aan | walked | ||

| 'Masses of children have walked behind the parade.' | ||||||||

The locational and directional examples in (277)/(278) also seem to differ in another respect. The examples in (280) show that the former differ from the latter in allowing the split pattern under a neutral (i.e. non-contrastive) intonation pattern; cf. also Section 32.2.5, sub IIIA1.

| a. | Tegen de muur | stond | een ladder | aan. | location | |

| against the wall | stood | a ladder | aan |

| a'. | Tegen de muur | zette | Jan een ladder | aan. | change of location | |

| against the wall | put | Jan a ladder | aan |

| b. | * | Tegen de ladder | liep | Jan | aan. | direction |

| against the wall | walked | Jan | aan |

| b'. | * | Achter de optocht | liepen | veel kinderen | aan. | direction |

| behind the parade | walked | many children | aan |

This suggests that achter ... aan had better not be considered a circumposition in the locational constructions. Such a distinction between the phrases in the directional and the locational constructions is also supported by the data in (281). In the (change of) locational constructions the element aan can occupy a position within the clause-final verb cluster, which is a typical property of particles, while this leads to a degraded result in the directional construction.

| a. | dat | de ladder | tegen de muur | heeft | aan | gestaan. | location | |

| that | the ladder | against the wall | has | aan | stood |

| a'. | dat | Jan de ladder | tegen de muur | heeft | aan | gezet. | change of location | |

| that | Jan the ladder | against the wall | has | aan | put |

| b. | ? | dat | Jan tegen | de ladder | is | aan | gelopen. | direction |

| that | Jan against | the ladder | has | aan | walked |

| b'. | ? | dat | er | veel kinderen | achter | de | optocht zijn | aan | gelopen. |

| that | there | many children | behind | the parade | are | aan | walked |

We leave it to future research to investigate in more detail whether the proposed analysis for the different syntactic behavior of tegen ... aan and achter ... aan is on the right track; cf. Section 32.2.5, sub IIIA1, for more relevant information.

There are two circumpositions with af as their second member: van ... af and op ... af. The examples in (282) seem to show that the circumpositional phrase van ... af can indicate a (change of) location, although (282a) does not sound entirely natural.

| a. | ? | Het boek | lag | van de tafel | (af). | location |

| the book | lay | from the table | af | |||

| 'The book was removed/had fallen from the table.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan legde | het boek van de tafel | (af). | change of location | |

| Jan put | the book from the table | af | |||

| 'Jan removed the book from the table.' | |||||

Similar constructions are not possible with op ... af. The examples in (283) show that the two circumpositional phrases can both be used directionally.

| a. | Jan reed | van de berg | ?(af). | direction | |

| Jan drove | from the mountain | af | |||

| 'Jan drove down from the mountain.' | |||||

| b. | Jan liep | op zijn tegenstander | *(af). | direction | |

| Jan walked | towards his opponent | af |

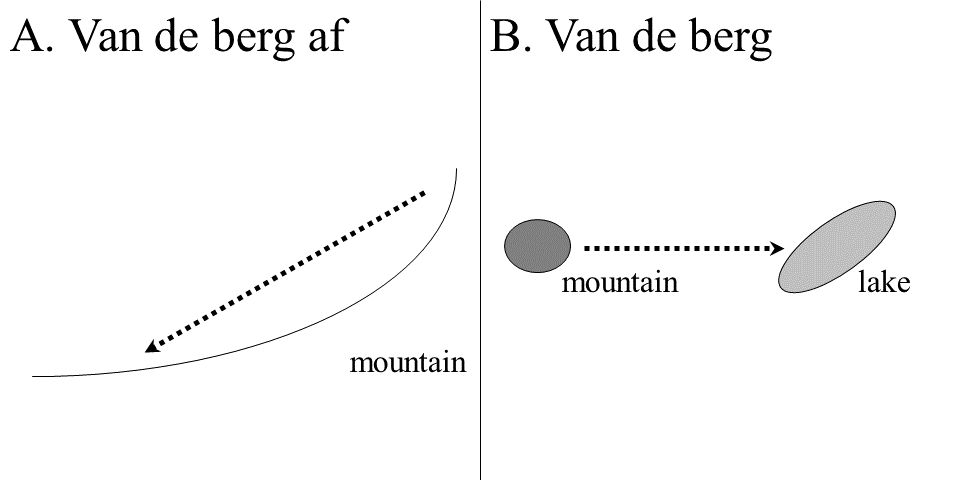

In the locational examples in (282), the element af can be omitted without a clear change in meaning; the presence of af merely seems to emphasize that the physical contact between the located object and the reference object has been broken. At first glance, it seems that af can also be dropped in the directional example in (283a), but this may be due to the fact that the preposition van can also be used as a directional preposition. It is therefore important to note that the absence or presence of af affects the meaning of the clause: if af is present, as in (284a), the implied path goes down along the surface of the mountain, as depicted in Figure 32A; if af is absent, as in (284b), the clause can also express that Jan is moving away from the mountain, as in Figure 32B.

| a. | Jan reed | van de berg | af. | |

| Jan drove | from the mountain | af | ||

| 'Jan drove down from the mountain.' | ||||

| b. | Jan reed | van de berg | ?(naar het meer). | |

| Jan drove | from the mountain | to the lake | ||

| 'Jan drove from the mountain to the lake.' | ||||

This discussion supports the idea that, only if af is present, it is necessarily implied that the starting point of the implied path is situated on the mountain. Since the element af cannot be omitted in the case of (283b), it seems safe to conclude that it is indeed obligatory in the directional construction, and that the case without af involves the directional prepositional phrase van de berg.

The (a)-examples in (285) show that the circumposition tussen ... door cannot be used to indicate a (change of) location. The grammatical use of the circumpositional phrase in (285b) is directional. The same thing holds for onder ... door, which we will not illustrate here.

| a. | Het boek | ligt | tussen de andere spullen | (*door). | location | |

| the book | lies | between the other things | door |

| a'. | Jan legt | het boek | tussen de andere spullen | (*door). | change of location | |

| Jan puts | the book | between the other things | door |

| b. | Jan reed | tussen de bomen | #(door). | direction | |

| Jan drove | between the trees | door | |||

| 'Jan drove along a path that goes through the trees.' | |||||

The number sign in (285b) is used to indicate that door must be present; without it, the directional meaning is lost. This can be easily illustrated by considering the perfect-tense constructions in (286): the verb rijden with the auxiliary zijn is a verb of traversing, which requires a directional complementive, and door is obligatory; the verb rijden with the auxiliary hebben is an activity verb, which is compatible with a locational adverbial PP, and door is preferably omitted.

| a. | Jan is tussen de bomen | *?(door) | gereden. | |

| Jan is between the trees | door | driven | ||

| 'Jan has driven through in between the trees.' | ||||

| b. | Jan heeft | tussen de bomen | (?door) | gereden. | |

| Jan has | between the trees | door | driven | ||

| 'Jan has driven along a path that goes through the trees.' | |||||

The (a)-examples in (287) show that circumpositions with heen as their second member can indicate a (change of) location. The circumpositional phrase in (287b) is directional. In the (a)-examples, heen can be dropped without any clear effect on the meaning. This is also the case in (287b), which is not surprising because over can also be used as a directional preposition. The same thing is at least marginally true for langsalong and omaround.

| a. | Over | zijn schouder | (heen) | hing | een kleurige das. | location | |

| over | his shoulder | heen | hung | a colorful scarf | |||

| 'A colorful scarf was hanging over his shoulder.' | |||||||

| a'. | Over | zijn schouder | (heen) | hing | Jan een kleurige das. | change of location | |

| over | his shoulder | heen | hung | Jan a colorful scarf | |||

| 'Jan hung a colorful scarf over his shoulder.' | |||||||

| b. | Jan reed | over de brug | (heen). | direction | |

| Jan drove | over the bridge | heen | |||

| 'Jan drove over the bridge.' | |||||

It is not particularly clear what semantic effect dropping of heen has on example (287b). It has been suggested that heen indicates a movement away from the speaker (Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal; entry heenII) or some other anchoring point. However, this meaning certainly does not apply to the non-directional cases in (287) nor does it seem to provide a correct characterization for directional examples such as (288), where the distance between the reference object (here, the speaker) and the located object need not increase.

| Jan is drie keer | om mij | heen | gefietst. | ||

| Jan is three time | around me | heen | cycled | ||

| 'Jan has traversed the path around me three times on bicycle.' | |||||

It should be noted, however, that heen can be used as a verbal particle and that in this case, it does have the implication of movement away from the speaker or some other anchoring point. However, these cases often have an archaic or idiomatic flavor. Some other more or less idiomatic examples are given in (289).

| a. | Jan is heen | gegaan. | |

| Jan is away | gone | ||

| 'Jan has passed away.' | |||

| b. | Loop heen! | |

| walk away | ||

| 'Go away!' or 'You're kidding.' |

| c. | Ik | ga | er | morgen | heen. | |

| I | go | there | tomorrow | heen | ||

| 'I will go there tomorrow' or 'I will visit him/her/it/them tomorrow.' | ||||||

That (289a) is idiomatic is beyond doubt. As for (289b), in addition to its idiomatic meaning “youʼre kidding!”, the more literal meaning “go away!” is peculiar in that this combination usually occurs in the imperative mood: the indicative form Jan liep heenJan walked away is very formal and perhaps even archaic. That (289c) is idiomatic may be less obvious; it is supported by the fact that the locational pro-form erthere cannot be replaced by a full PP, as shown by the fact that examples such as (290) are completely ungrammatical with heen present (the same goes for iets er heen brengento bring something to NP).

| Ik | ga | morgen | naar oma/de bioscoop | (*heen). | ||

| I | go | tomorrow | to granny/the cinema | heen | ||

| 'I will visit granny /go to the movies tomorrow.' | ||||||

More idiomatic expressions with heen are given in (291) .

| a. | achter | iets | heen | gaan | |

| after | something | heen | go | ||

| 'to chase/follow something up' | |||||

| b. | achter | iets/iemand | heen | zitten | |

| after | something/someone | heen | sit | ||

| 'to keep onto something/someone' | |||||

The (a)-examples in (292) show that the circumpositional phrase tussen de meisjes in can indicate a (change of) location; however, this is not easily possible with tegen de stroom in. Both circumpositional phrases with in as their second member can be used directionally. This is illustrated in (292b) for tegen de stroom in: this example expresses that the speaker is traversing a path that goes in the opposite direction of the current.

| a. | Jan zit | tussen de twee meisjes | (in). | location | |

| Jan sits | between the two girls | in | |||

| 'Jan is sitting in between the two girls.' | |||||

| a'. | Marie zet | Jan | tussen de twee meisjes | (in). | change of location | |

| Marie puts | Jan | between the two girls | in | |||

| 'Marie is putting Jan in between the two girls.' | ||||||

| b. | Tegen | de stroom | *(in) | zwem | ik | niet | graag. | direction | |

| against | the current | in | swim | I | not | gladly | |||

| 'I do not like to swim against the current.' | |||||||||

The element in can be omitted in the non-directional (a)-examples without any notable difference in meaning; in seems to act as a mere emphasizer. In (292b), on the other hand, in must be present; without it, the directional meaning is lost.

Circumpositions with langs as their second member are used only as directional adpositions; the non-directional (a)-examples in (293) are unacceptable with the element langs present.

| a. | De bloemen | liggen | achter het huis | (*langs). | location | |

| the flowers | lie | behind the house | langs | |||

| 'The flowers lie behind the house.' | ||||||

| a'. | Jan legt | de bloemen | achter het huis | (*langs). | change of location | |

| Jan puts | the flowers | behind the house | langs | |||

| 'Jan is putting the flowers behind the house.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan wandelt | achter | het huis | #(langs). | direction | |

| Jan walks | behind | the house | langs | |||

| 'Jan is walking along the back of the house.' | ||||||

In (293b), the element langs is obligatory; without it the directional meaning is lost. This can be easily illustrated by considering the perfect-tense constructions in (294): if the verb wandelen takes the auxiliary zijn, it is a verb of traversing, which requires a directional complementive and langs is obligatory; if it takes the auxiliary hebben, it is an activity verb, which is compatible with a locational adverbial PP and langs is preferably omitted.

| a. | Jan is achter | het huis | *(langs) | gewandeld. | |

| Jan is behind | the house | langs | walked | ||

| 'Jan has walked along the back of the house.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft achter | het huis | (??langs) | gewandeld. | |

| Jan has behind | the house | langs | walked | ||

| 'Jan has walked behind the house.' | |||||

The examples in (295) show that circumpositions with om as their second member are used only as directional adpositions; the non-directional (a)-examples are only acceptable without the element om. In example (295c) we are dealing with a metaphorical use of the circumpositional phrase buiten de administratie om.

| a. | De bloemen | liggen | achter het huis | (*om). | location | |

| the flowers | lie | behind the house | om | |||

| 'The flowers are lying behind the house.' | ||||||

| a'. | Jan legt | de bloemen | achter het huis | (*om). | change of location | |

| Jan puts | the flowers | behind the house | om | |||

| 'Jan is putting the flowers behind the house.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan liep | achter | het huis | #(om). | direction | |

| Jan walked | behind | the house | om | |||

| 'Jan walked around the back of the house.' | ||||||

| c. | Deze procedure | loopt | buiten | de administratie | *(om). | |

| this procedure | goes | outside | the administration | om | ||

| 'The administration is not involved in this procedure.' | ||||||

In (295b&c), the element om is obligatory; without it, the directional meaning of (295b) is lost and (295c) becomes ungrammatical. The loss of the directional meaning of (295b) can again be illustrated by considering the perfect-tense constructions in (296): if the verb lopen takes the auxiliary zijn, it is a verb of traversing, which requires a directional complementive and makes om is obligatory; if it takes the auxiliary hebben, it is an activity verb, which is compatible with a locational adverbial PP while om is preferably dropped.

| a. | Jan is achter | het huis | *(om) | gewandeld. | |

| Jan is behind | the house | om | walked | ||

| 'Jan has walked around the back of the house.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | achter | het huis | (??om) | gewandeld. | |

| Jan has | behind | the house | om | walked |

The examples in (297) show that the circumposition tegen ... op can only be used as a directional adposition; the non-directional (a)-examples are only acceptable without the element op. In example (297c), we are dealing with the idiomatic construction tegen de klippen op werken.

| a. | De ladder | stond | tegen de muur | (??op). | location | |

| the ladder | stood | against the wall | op | |||

| 'The ladder stood against the wall.' | ||||||

| a'. | Marie zette | de ladder | tegen de muur | (??op). | change of location | |

| Marie put | the ladder | against the wall | op | |||

| 'Marie put the ladder against the wall.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan klimt | tegen de muur | #(op). | direction | |

| Jan climbs | against the wall | op | |||

| 'Jan is climbing up against the wall.' | |||||

| c. | Jan werkt | tegen | de klippen | *(op). | |

| Jan works | against | the cliffs | up | ||

| 'Jan is working extremely hard.' | |||||

The element op is obligatory in the directional construction; without it the directional meaning of (297b) is lost and (297c) becomes ungrammatical. For people who accept (298b) without op, the verb is an activity verb and the PP functions as an adverbial phrase.

| a. | Jan is | tegen de berg | *(op) | geklommen. | |

| Jan is | against the mountain | op | climbed | ||

| 'Jan has climbed the mountain.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | tegen de berg | ?(*?op) | geklommen. | |

| Jan has | against the mountain | op | climbed |

The examples in (299) show that the circumposition tot ... toe cannot easily be used to denote a (change of) location.

| a. | De stenen | liggen | tot de heg | (*?toe). | location | |

| the stones | lie | until the hedge | toe | |||

| 'The stones are lying up to the hedge.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan legt | de stenen | tot de heg | (*?toe). | change of location | |

| Jan lays | the stones | until the hedge | toe | |||

| 'Jan is laying the stones up to the hedge.' | ||||||

The examples seem to improve slightly when we add a van-PP, as in (300). However, it is doubtful whether the circumpositions in these cases refer to a (change of) location: the van-PP is directional (it indicates the starting point of the path), so we expect that the circumpositional phrase is also directional (it indicates the endpoint of the path). Therefore, the examples in (300) are directional, and have an extent reading comparable to Het pad loopt van hier tot aan de heg (toe)The path extends from here to the hedge.

| a. | De stenen | liggen | van hier | tot de heg | (?toe). | |

| the stones | lie | from here | until the hedge | toe |

| b. | Jan legt | de stenen | van hier | tot de heg | (?toe). | |

| Jan lays | the stones | from here | until the hedge | toe | ||

| 'Jan is laying the stones from here to the hedge.' | ||||||

As is shown in (301), the examples in (299) become fully grammatical when the noun phrase de heg is preceded by the element aan. It has been suggested that tot aan ... toe is also a circumposition, albeit of a slightly more complex kind. However, there are reasons to reject this suggestion and to assume that the preposition tot is capable of taking an adpositional complement (cf. Section 33.2.1, sub III); we may therefore be dealing with a case in which the circumposition tot ... toe takes a PP-complement (i.e. aan de heg).

| a. | De stenen | liggen | tot | aan de heg | (toe). | |

| the stones | lie | until | at the hedge | toe |

| b. | Jan legt | de stenen | tot | aan de heg | (toe). | |

| Jan lays | the stones | until | at the hedge | toe | ||

| 'Jan is laying the stones from here to the hedge.' | ||||||

We can probably conclude from this discussion that circumpositions with toe are only directional, as in (302). In these examples, toe seems to be optional, which is not surprising because the prepositions naarto and totuntil are both directional themselves; the meaning contribution of toe seems to be mainly a case of adding emphasis. Note that (302b) can also be made more complex by adding the element aan; we will return to such examples in Section 33.2.1, sub III.

| a. | Jan | reed | naar Peter | (toe). | |

| Jan | drove | to Peter | toe | ||

| 'Jan drove to Peter.' | |||||

| b. | Jan reed | tot | (aan) | de grens | ((aan) toe). | |

| Jan drove | until | aan | the border | toe | ||

| 'Jan drove until the border.' | ||||||

It is not easy to determine whether circumpositions with uit as the second member can be used to refer to a (change of) location. A verb that seems to easily allow the location reading is stekento stick in (303), but it seems that the change-of-location reading is degraded, as is shown in (303b).

| a. | Het formulier | stak | onder zijn papieren | uit. | location | |

| the form | stuck | under his papers | uit | |||

| 'The form protruded from under his papers.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Jan stak | het formulier | onder zijn papieren | uit. | change of location |

| Jan stuck | the form | under his papers | uit |

The change-of-location construction seems to be possible in (304b), but it is not clear whether we can infer anything from this, because uit can also be used as a verbal particle (cf. uitstekento stick out). This can be seen from the fact that the PP boven de menigte is optional. In fact, the same in fact holds for onder zijn papieren in (303a).

| a. | Jans hand | stak | (boven de menigte) | uit. | |

| Janʼs hand | stuck | above the crowd | uit | ||

| 'Janʼs hand was sticking out above the crowd.' | |||||

| b. | Jan stak | zijn hand | (boven de menigte) | uit. | |

| Jan stuck | his hand | above the crowd | uit | ||

| 'Jan stuck out his hand above the crowd.' | |||||

Similar examples can be found in (305) with the verb hangento hang: the locational reading in (305a) is perfectly acceptable, but the corresponding change-of-location construction in (305b) is highly marked.

| a. | Haar rok | hing | onder haar jas | uit. | location | |

| her skirt | hung | under her coat | uit | |||

| 'Her skirt was sticking out from under her coat.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Marie hing | haar rok | onder haar jas | uit. | change of location |

| Marie hung | her skirt | under her coat | uit |

Nevertheless, it seems that the change-of-location reading is possible with a verb like trekkento pull: the examples in (303b) and (305b) become perfectly acceptable with this verb, as shown in (306). Note that the sequence onder + NP cannot be omitted: this results either in unacceptability or in a change of meaning (cf. Marie trok haar rok uit means “Marie took off her skirt, i.e. undressed”).

| a. | Jan trok | het formulier | *(onder zijn papieren) | uit. | |

| Jan pulled | the form | under his papers | uit | ||

| 'Jan pulled the form out from under his papers.' | |||||

| b. | Marie trok | haar rok | #(onder haar jas) | uit. | |

| Marie pulled | her skirt | under her coat | uit | ||

| 'Marie pulled her skirt out from under the coat.' | |||||

The examples in (306) suggest that the unacceptability of (303b) and (305b) need not show that the change-of-location reading is impossible, since it may be due to some (poorly understood) constraint on the verb. However, whatever the conclusion about circumpositions with uit allowing a change-of-location reading, it is clear that they can be used to refer to directions. An example is given in (307).

| De fanfare | liep | voor | de optocht | #(uit). | ||

| the brass band | walked | before | the parade | uit | ||

| 'The brass band walked ahead the parade.' | ||||||

Example (307) shows that the element uit is obligatory in the directional construction; if it is not present the directional meaning is lost. This can again be illustrated by considering the perfect-tense constructions in (308): if the verb lopen takes the auxiliary zijn, it is a verb of traversing, requiring a directional complementive, and uit is obligatory; if the verb takes the auxiliary hebben, it is an activity verb, which is compatible with a locational adverbial PP, and uit is preferably omitted.

| a. | De fanfare | is voor | de optocht | *(uit) | gelopen. | |

| the brass band | is before | the parade | uit | walked | ||

| 'The brass band has walked in front of (= led) the parade.' | ||||||

| b. | De fanfare | heeft | voor | de optocht | (??uit) | gelopen. | |

| the brass band | has | before | the parade | uit | walked | ||

| 'The brass band has walked in front of (≠ led) the parade.' | |||||||

The examples in (309) show that circumpositions with vandaan as their second member are only used as directional adpositions. The non-directional (a)-examples are only acceptable without the element vandaan.

| a. | De bloemen | liggen | achter het huis | (*vandaan). | location | |

| the flowers | lie | behind the house | vandaan | |||

| 'The flowers lie behind the house.' | ||||||

| a'. | Jan legt | de bloemen | achter het huis | (*vandaan). | change of location | |

| Jan puts | the flowers | behind the house | vandaan | |||

| 'Jan lays the flowers behind the house.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan fietst | achter de bomen | #(vandaan). | direction | |

| Jan cycles | behind the trees | vandaan | |||

| 'Jan cycles from behind the trees.' | |||||

The element vandaan is obligatorily present in the directional construction in (309b); without it, the directional meaning is lost. This is illustrated by the perfect-tense constructions in (310): if the verb fietsen takes the auxiliary zijn, it is a verb of traversing, requiring a directional complementive, and vandaan is obligatory; if the verb takes hebben, it is an activity verb, which is compatible with a locational adverbial PP, and vandaan must be dropped.

| a. | Jan is achter de bomen | *(vandaan) | gefietst. | |

| Jan is behind the trees | vandaan | cycled | ||

| 'Jan has cycled from behind the trees.' | ||||

| b. | Jan heeft | achter de bomen | (*vandaan) | gereden. | |

| Jan has | behind the trees | vandaan | cycled | ||

| 'Jan has cycled behind the trees.' | |||||

Circumpositional phrases with vandaan are regularly preceded by the preposition van; cf. (311a). However, this element is not part of the circumposition but a regular preposition, as will be clear from the fact that the circumpositional phrase can be replaced by the adpositional pro-form daarthere; cf. (311b). We return to this point in Section 33.2.1.

| a. | Jan kwam | van | achter de bomen vandaan. | |

| Jan came | from | behind the trees vandaan | ||

| 'Jan came from behind the trees.' | ||||

| b. | Jan kwam | van daar. | |

| Jan came | from there |

For completeness, note that the construction in (312) seems to be the antonym of the idiomatic construction Ik ga er heen in (289c), and is therefore in all likelihood also an idiomatic expression.

| Ik | kom | er | net | vandaan. | ||

| I | come | there | just | from | ||

| 'I just come from there.' or 'I have just visited him/her/it/them.' | ||||||

Table 19 again provides the list of circumpositions and indicates whether they can be used to indicate a (change of) location or a direction. We have also indicated whether or not the second part of the (alleged) circumposition must be present in order for the circumpositional phrase to express the locational/directional meaning.

| circumposition | locational reading | directional reading | ||

| available | particle | available | 2nd part | |

| achter ... aan | — | N/A | + | obligatory |

| tegen ... aan | + | optional | ||

| van ... af | + | optional | + | obligatory but see (283a) |

| op ... af | — | N/A | ||

| onder/tussen ... door | — | N/A | + | obligatory |

| door/langs/om/over ... heen | + | optional | + | obligatory |

| tegen ... in | — | N/A | + | obligatory |

| tussen ... in | + | optional | ||

| achter/boven/onder/voor ... langs | — | N/A | + | obligatory |

| achter/buiten/voor ... om | — | N/A | + | obligatory |

| tegen ... op | — | N/A | + | obligatory |

| naar/tot ... toe | — | N/A | + | optional |

| achter/boven/onder/ tussen/voor ... uit | location: + change of location: — | optional; meaning effect | + | obligatory |

| achter/bij/om/onder/ tussen/van ... vandaan | — | N/A | + | obligatory |

The table shows that all circumpositions can have a directional meaning and that the second part of the circumposition is obligatorily present in this case. The alleged cases in which it is not present are due to the fact that the first part of circumpositions can sometimes also occur as a preposition with a directional meaning.

The table also shows that only a small subset of the circumpositions is used in locational constructions. Moreover, the second part usually has little effect on the meaning expressed. It is therefore valid to ask whether we are really dealing with circumpositions in these cases, or merely with prepositional phrases that are somehow combined with a particle. We strongly suspect the latter, although more research is needed before we can draw a firm conclusion.

We would like to conclude this section by repeating that most circumpositional phrases also allow an extent reading. The examples in (313) show that only the circumpositions ending in aan, uit and vandaan seem to resist this use.

| De weg loopt ... | ||

| the road runs |

| a. | *? | tegen | het bos | aan |

| against | the forest | aan |

| b. | van | de berg | af | |

| from | the mountain | af |

| c. | tussen | de bomen | door | |

| between | the trees | door |

| d. | over | de brug | heen | |

| over | the bridge | heen |

| e. | ? | tussen | de bomen | in |

| between | the trees | in |

| f. | achter | het huis | langs | |

| behind | the house | langs |

| g. | voor | het huis | om | |

| in.front.of | the house | om |

| h. | tegen | de berg | op | |

| against | the mountain | op |

| i. | naar | het hek | toe | |

| towards | the gate | toe |

| j. | * | achter | het bos | uit |

| behind | the forest | uit |

| k. | * | achter | het bos | vandaan |

| behind | the forest | vandaan |