- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section discusses the meaning contribution of spatiotemporal adverbial phrases in more detail. The basic observation is that clauses can contain more than one temporal or locational adverbial, as again illustrated by the sentences in (113): cf. also Section 8.2.2, sub IX. The adverbials preceding the modal adverb (i.e. gisteren and in Amsterdam) function as clause adverbials, while those following the modal (om drie uur and bij zijn tante) function as VP adverbials.

| a. | Jan is gisteren | waarschijnlijk | om drie uur | vertrokken. | |

| Jan is yesterday | probably | at 3 o’clock | left | ||

| 'Jan probably left at 3 oʼclock yesterday.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | in Amsterdam | waarschijnlijk | bij zijn tante | gelogeerd. | |

| Jan has | in Amsterdam | probably | with his aunt | stayed | ||

| 'Jan probably stayed with his aunt in Amsterdam.' | ||||||

This raises the question of how the meaning contributions of these clause and VP adverbials differ. Our starting point for answering this question will be binary tense theory: cf. Te Winkel (1866) and Verkuyl (2008). This theory was introduced in Section 1.5.1 and used in the description of the Dutch tense system in Section 1.5.4. Although we assume that the reader is familiar with these sections, we begin in Subsection I by repeating some of the key findings relevant to the present topic. Subsection II then discusses the semantic contribution of the two types of temporal adverbials: we will argue that VP adverbials are modifiers of eventualities, while clause adverbials modify the temporal domains in which these eventualities occur. Subsection III will extend this proposal to locational adverbials.

Binary tense theory claims that the mental representation of tense is based on the three binary distinctions in (114). Languages differ in the means used to express these oppositions: this can be done within the verbal system by inflection and/or auxiliaries, but it can also involve the use of adverbial phrases, aspectual markers, pragmatic information, and so on; cf. Verkuyl (2008).

| a. | [±past]: present versus past |

| b. | [±posterior]: future versus non-future |

| c. | [±perfect]: imperfect versus perfect |

Verkuyl (2008) claims that Dutch expresses all the oppositions in (114) in the verbal system: [+past] is expressed by inflection, [+posterior] by the verb zullenwill, and [+perfect] by the auxiliaries hebbento have and zijnto be. This leads to the eight-way distinction between tenses in Table 1, which is used in most Dutch grammars.

| present | past | ||

| synchronous | imperfect | present Ik wandel. I walk | simple past Ik wandelde. I walked |

| perfect | present perfect Ik heb gewandeld. I have walked | past perfect Ik had gewandeld. I had walked | |

| posterior | imperfect | future Ik zal wandelen. I will walk | future in the past Ik zou wandelen. I would walk |

| perfect | future perfect Ik zal hebben gewandeld. I will have walked | future perfect in the past Ik zou hebben gewandeld. I would have walked | |

However, our discussion in Sections 1.5.2 and 1.5.4 departs from Verkuyl’s original claim that zullenwill can be used as a future auxiliary and argues that it is an epistemic modal verb in all its uses. We have further argued that it is only due to pragmatic considerations that utterances with zullen are sometimes interpreted with a future time reference; cf. also Broekhuis & Verkuyl (2014). If this is correct, the Dutch verbal system only expresses the binary features [±past] and [±perfect], and thus does not make an eightfold but only a fourfold tense distinction, as in Table 2. Since zullen is no longer used to define a separate set of future tenses, posteriority must be expressed by using e.g. adverbials such as morgentomorrow, as in Jan vertrekt morgenJan will leave tomorrow.

| present | past | |

| imperfect | simple present Ik wandel/Ik zal wandelen. I walk/I will walk | simple past Ik wandelde/Ik zou wandelen. I walked/I would walk |

| perfect | present perfect Ik heb gewandeld/ Ik zal hebben gewandeld. I have walked/I will have walked | past perfect Ik had gewandeld/ Ik zou hebben gewandeld. I had walked/I would have walked |

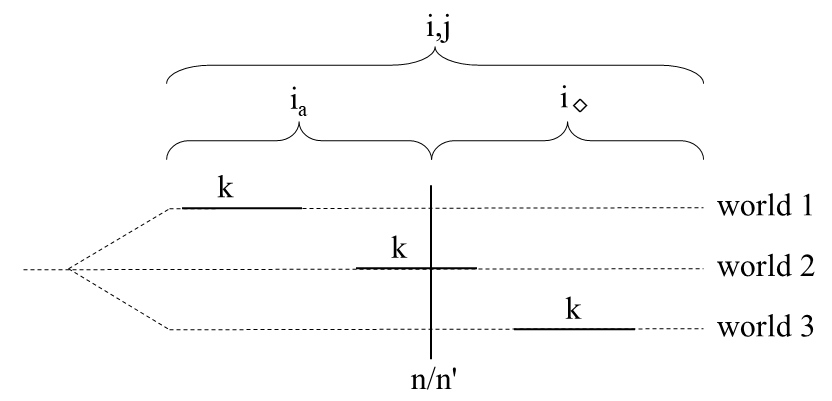

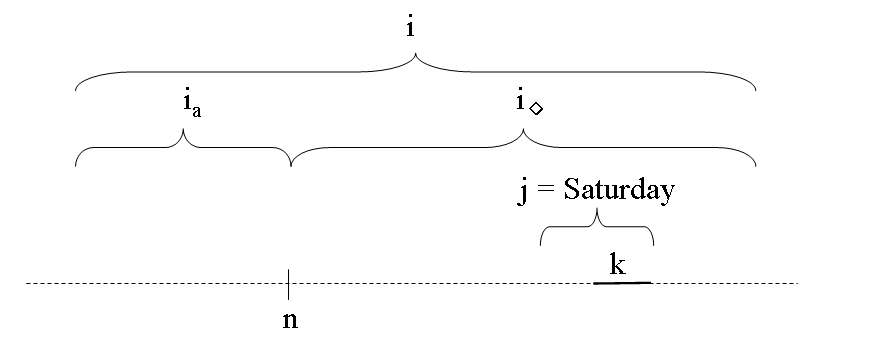

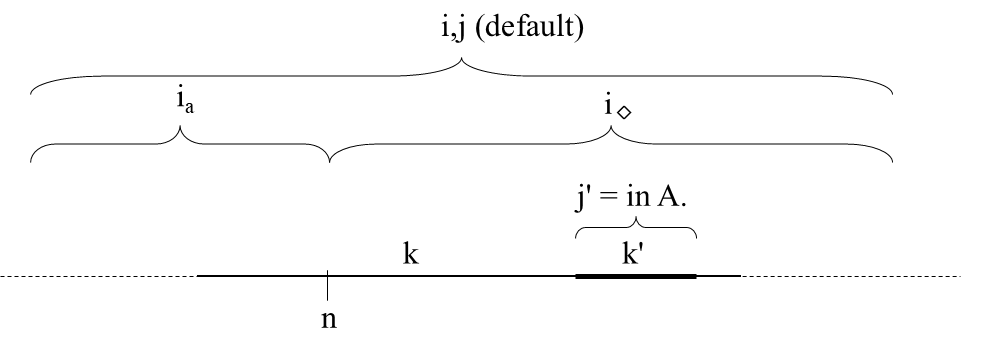

The revised view of the verbal tense system of Dutch implies that utterances in simple present/past should in principle be able to refer to any subinterval within present/past-tense interval i. This is illustrated in Figure 1, where the dotted line indicates the time line, for different possible worlds in which simple present/past sentences like Ik wandelI am walking and Ik wandeldeI walked are predicted to be true; note that the number of possible worlds is in principle infinite and that we have simply made a selection that suits our purpose. World 1 represents the situation in which eventuality k precedes speech time n or virtual speech-time-in-the-past n', i.e. the situation in which k is located in the actualized part ia of present/past-tense interval i. World 3 represents the situation in which k follows n/n', i.e. in which it is located in the non-actualized part i◊ of present/past-tense interval i. World 2, finally, represents the situation in which k occurs at n/n'. We have not yet mentioned time interval j, but its function will become clear shortly.

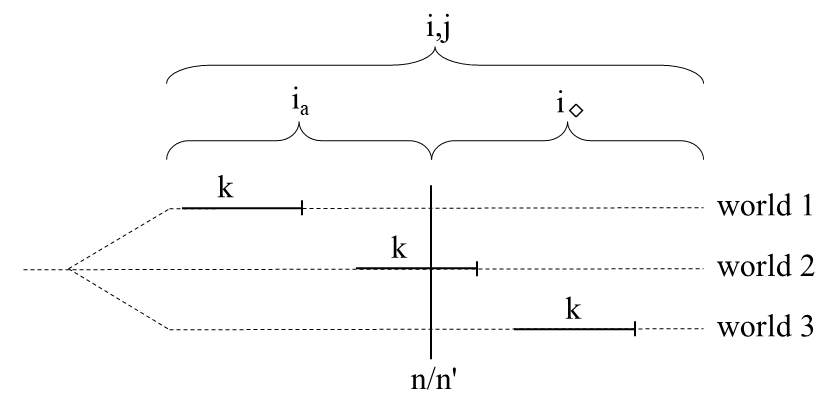

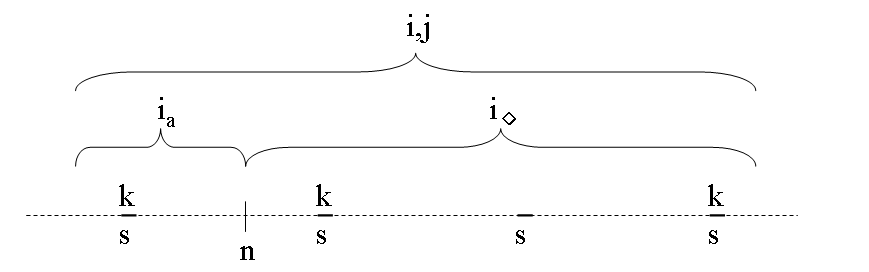

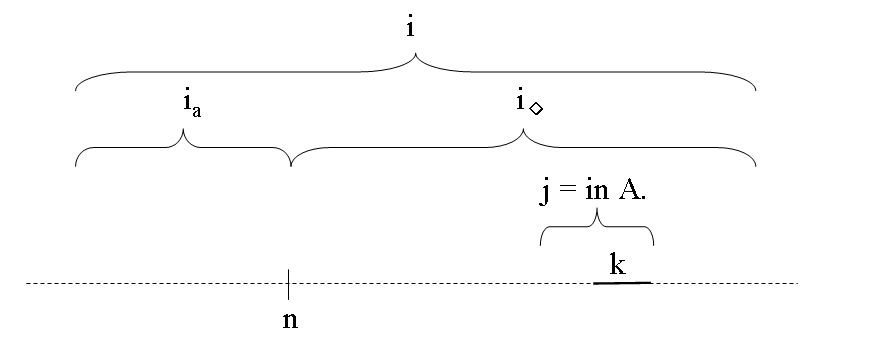

The representation of perfect-tense examples like Ik heb gewandeldI have walked and Ik had gewandeldI had walked in Figure 2 is virtually identical to that in Figure 1; the only difference is that eventuality k is presented as a completed autonomous unit within present/past-tense interval i, as indicated by the vertical line at the right edge of k.

The proposal outlined above overgenerates considerably. For example, it predicts that any simple-present sentence could be used to refer to the situation depicted in world 1 in Figure 1, whereas we would use a present perfect in most cases. However, Section 1.5.4.1 has shown that the prediction is actually correct in the more specific situation depicted in Figure 1, in which the speaker has a knowledge gap about the state of affairs in the actual world prior to speech time n (indicated by the fact that the split-off point of the possible worlds precedes n); example (115) can be used if the speaker does not know whether Els has already finished reading.

| Els leest | vanmorgen | mijn artikel. | ||

| Els reads | this.morning | my paper | ||

| 'Els is reading my paper this morning.' | ||||

In the absence of such a knowledge gap, example (115) is infelicitous. The reason for this is pragmatic in nature. If the speaker knows that eventuality k precedes n, he can present k as a discrete, bounded unit that has been completed within the actualized part of time interval ia of present-tense interval i: since this can be described more precisely by the present perfect, Grice’s °maxim of quantity prohibits the use of the less informative simple present (cf. Sections 1.5.4.1, sub II, and 1.5.4.2, sub II, for further discussion). This reasoning rests crucially on the assumption that the tenses in Table 2 have a specific default interpretation: for example, simple present-tense clauses refer by default to the situation depicted in world 2 in Figure 1, while present perfect clauses refer by default to the situation depicted in world 1 in Figure 2; reference to the situations in the alternative worlds is possible, but only if the context provides special clues indicating that this is indeed what the speaker intends.

The following subsections will show that temporal and locational adverbials play an important role in providing such clues. The discussion will pay particular attention to how their status as clause adverbial or VP adverbial affects their meaning contribution. Subsection II begins with a discussion of temporal adverbials; it adopts the hypothesis put forward in Sections 1.5.4.1, sub III, and 1.5.4.2, sub III, that while temporal VP adverbials modify eventuality k directly, temporal clause adverbials do so indirectly by modifying the so-called present j of k, i.e. the subdomain of present/past-tense interval i within which k must be located and which is taken to be identical to i in the default case (as indicated in the two figures above). Subsection III will show that something similar holds for locational adverbials.

This subsection discusses the semantic contribution of the temporal adverbials to the meaning of the clause. We will adopt the standard assumption from Section 8.2.1 that VP adverbials are modifiers of the proposition expressed by the lexical projection of the verb. In terms of the tense representations in Figure 1 and Figure 2, this amounts to saying that VP adverbials are modifiers of an eventuality k. This is obviously true for durational adverbials such as drie uur (lang)for three hours in (116), which simply indicate the duration of k.

| Jan heeft | drie uur (lang) | gezongen. | ||

| Jan has | three hour long | sung | ||

| 'Jan has been singing for three hours.' | ||||

This is also true for punctual adverbials such as om 15.00 uurat 3 p.m. in (117), which locates the eventuality of Jan’s departure at 3 p.m. in the non-actualized part i◊ of present-tense interval i (where the choice of i◊ is due to the use of the simple present for the pragmatic reason discussed in Subsection I). The default interpretation of (117a) is that Jan will leave at 3 o’clock today, but this can easily be overridden by contextual factors; this is especially clear in example (117b), in which the clause adverbial morgentomorrow is used to indicate that Jan’s departure will take place at 3 o’clock on the first day following speech time n. Note that we have added the modal adverb waarschijnlijkprobably in order to distinguish between VP and clause adverbials; here we will ignore its semantic distribution (i.e. the introduction of possible worlds) in our discussion for the sake of simplicity.

| a. | Jan vertrekt | (waarschijnlijk) | om 15.00 uur. | |

| Jan leaves | probably | at 3 p.m. | ||

| 'Jan will (probably) leave at 3 p.m.' | ||||

| b. | Jan vertrekt | morgen | (waarschijnlijk) | om 15.00 uur. | |

| Jan leaves | tomorrow | probably | at 3 p.m. | ||

| 'Jan will (probably) leave at 3 p.m. tomorrow.' | |||||

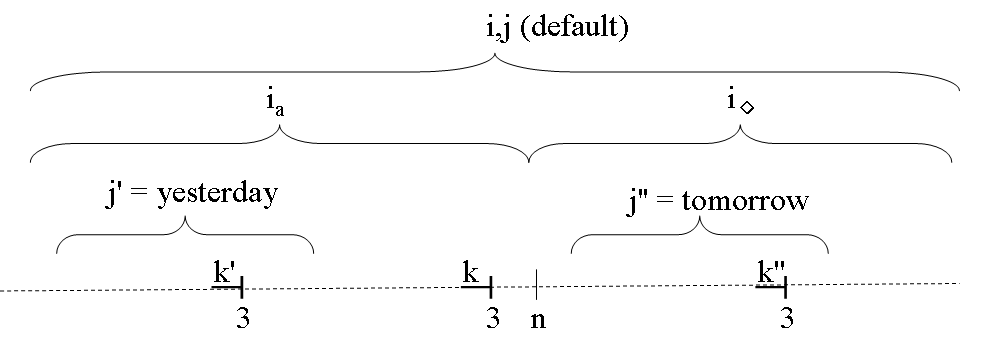

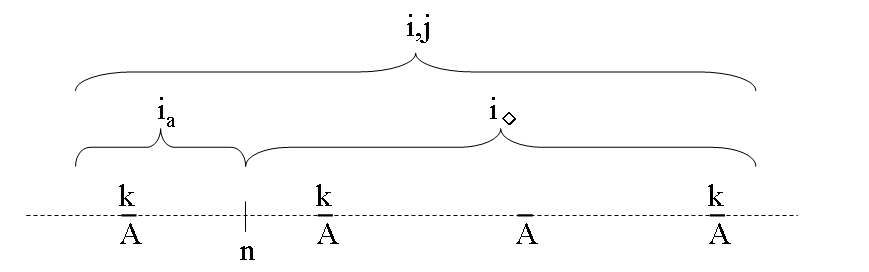

The simplest way to account for the meaning contribution of the clause adverbial morgentomorrow in (117b) is to assume that it modifies the present j of k: representation (118) shows that j is taken to be identical to i by default, but that the use of the temporal clause adverbial restricts j to a subdomain of i; for ease of presentation we have marked the non-default interpretation of j (and k) with a prime.

|

If we assume that sentence (117a) is uttered at noon, as indicated in representation (118), its default interpretation would be derived as follows: the present j of k is taken by default to be identical to the present-tense interval i. Since the simple present is again restricted to the non-actualized part i◊ of present-tense interval i for pragmatic reasons, the sentence refers to eventuality k, since this is the first occasion after speech time n that fits the description om 15.00 uur (indicated by the number 3 in representation (118)). Note in passing that the sentence would refer to k' by default if it were uttered at 10 p.m., since this would then be the first occasion after speech time n that fits the description om 15.00 uur. Representation (118) also shows that the default interpretation of (117a) is overridden in (117b) by the clause adverbial morgentomorrow, which restricts the present of the eventuality to time interval j': as a result, sentence (117b) can only refer to k'.

Now consider the present prefect examples in (119). If we assume that sentence (119a) is uttered in the evening, its default interpretation would be that eventuality k occurred earlier in the day. The examples in (119b&c) show that this default reading can easily be overridden by adding a clause adverbial such as gisterenyesterday or morgentomorrow.

| a. | Jan is | (waarschijnlijk) | om 15.00 uur | vertrokken. | |

| Jan is | probably | at 3 p.m. | left | ||

| 'Jan (probably) left at 3 p.m.' | |||||

| b. | Jan is gisteren | (waarschijnlijk) | om 15.00 uur | vertrokken. | |

| Jan is yesterday | probably | at 3 p.m. | left | ||

| 'Jan (probably) left at 3 p.m. yesterday.' | |||||

| c. | Jan is morgen | (waarschijnlijk) | om 15.00 uur | vertrokken. | |

| Jan is tomorrow | probably | at 3 p.m. | left | ||

| 'Jan will (probably) have left at 3 p.m. tomorrow.' | |||||

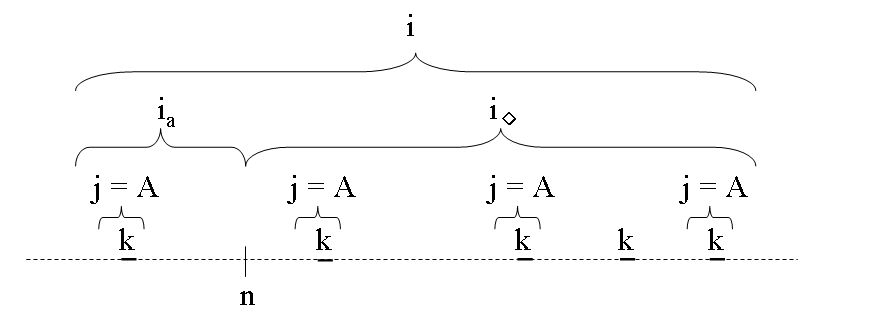

The simplest way to account for the meaning contribution of clause adverbials is again to assume that clause adverbials modify the present j of k; this is shown in representation (120), in which the various non-default interpretations of j and k are again indicated by primes.

|

The default interpretation would be derived as follows. First, the present j of the eventuality is taken to be identical to present-tense interval i. Since Subsection I has shown that the present perfect is restricted for pragmatic reasons to the actualized part ia of present-tense interval i, the sentence refers to eventuality k, since this is the first occasion preceding speech time n that fits the description om 15.00 uur; note in passing that the sentence would refer by default to k' if it were uttered at 8.00 a.m., since that would then be the first occasion prior to speech time n that fits the description om 15.00 uur. The default interpretation of (119a) is overridden in (119b) by the clause adverbial gisterenyesterday, which restricts the present j to the time interval j': as a result, sentence (119b) can only refer to k'. Similarly, the clause adverbial morgentomorrow in (119c) overrides the default interpretation of (119a) and restricts the present j to time interval j'': as a result, sentence (119c) can only refer to k''.

Representation (120) suggests that the VP adverbial om 15.00 uur locates the completion of the eventuality precisely at 3 p.m. However, this is not what this adverbial actually does: instead, it refers to a time at which the resulting state of eventuality k is true. This can be seen from examples such as (121), based on Janssen (1983), in which the adverbial al indicates that the completion of the eventuality of Jan’s departure took place before 3 p.m. This shows that the interpretations given in (120) are default readings of the modified structures in (119b&c), which can be overridden by adverbial modification (here: by al).

| Jan is | (waarschijnlijk) | om 15.00 uur | al | vertrokken. | ||

| Jan is | probably | at 3 p.m. | already | left | ||

| 'Jan will (probably) already have left at 3 p.m.' | ||||||

The examples discussed so far have all been in the present tense, but the account can also be applied to corresponding past tense cases (which will not be demonstrated here). We can conclude that the semantic interpretation of clauses with two temporal adverbials finds a natural accommodation and explanation in binary tense theory. This is a strong argument for binary tense theory, since Janssen (1983: fn.1) has shown that such cases are highly problematic for the Reichenbachian approach.

Binary tense theory also explains the strict word-order restriction that applies to the two adverbials. First, consider the examples in (122), which show that the adverbials morgentomorrow and om 15.00 uurat 3 p.m. can be used freely either as a VP adverbial or as a clause adverbial.

| a. | Jan gaat | waarschijnlijk | morgen/om 15.00 uur | naar de bioscoop. | |

| Jan goes | probably | tomorrow/at 3 p.m. | to the cinema | ||

| 'Jan will probably go to the cinema tomorrow/at 3 p.m.' | |||||

| b. | Jan gaat | morgen/om 15.00 uur | waarschijnlijk | naar de bioscoop. | |

| Jan goes | tomorrow/at 3 p.m. | probably | to the cinema | ||

| 'Jan will probably go to the cinema tomorrow/at 3 p.m.' | |||||

However, when the two adverbials co-occur in a single clause, there are severe restrictions on their distribution: the examples in (123) show that morgentomorrow must precede the modal adverbial waarschijnlijkprobably, while om 15.00 uur must follow it. Note in passing that we are not discussing cases such as Jan gaat morgen om 15.00 uur waarschijnlijk naar de bioscoop, in which the phrase morgen om 15.00 uur constitutes a single clause adverbial, as can be seen from the fact that it can occur in sentence-initial position as a whole: Morgen om 15.00 uur gaat Jan waarschijnlijk naar de bioscoop.

| a. | Jan gaat | morgen | waarschijnlijk | om 15.00 uur | naar de bioscoop. | |

| Jan goes | tomorrow | probably | at 3 p.m. | to the cinema | ||

| 'Jan will probably go to the cinema at 3 p.m. tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | $ | Jan gaat | om 15.00 uur | waarschijnlijk | morgen | naar de bioscoop. |

| Jan goes | at 3 p.m. | probably | tomorrow | to the cinema |

The use of the dollar sign in (123b) indicates that the reason for the unacceptability of this example is not syntactic but semantic in nature: it is simply incoherent. Since j contains eventuality k, the modifier of j must refer to a time interval which also contains the time (interval) indicated by the modifier of k. This is indeed the case in (123a), since morgen refers to a time interval which contains a point in time indicated by the adverbial om 15.00 uur, but this is not the case in (123b). For the same reason, an example such as (124) will only be felicitous if the addressee knows that there is a meeting the next day; if not, the addressee will correct the speaker or ask for more information about this meeting (Uh .. what meeting?).

| Jan geeft | morgen | waarschijnlijk | een lezing | na de vergadering. | ||

| Jan gives | tomorrow | probably | a talk | after the meeting | ||

| 'Jan will probably give a talk after the meeting tomorrow.' | ||||||

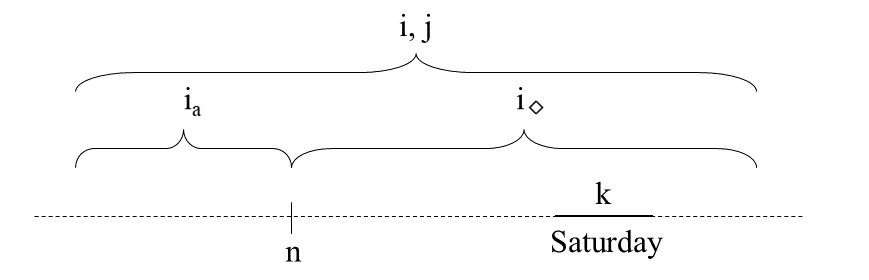

It is often difficult to determine the exact semantic difference between using an adverbial as a VP adverbial or as a clause adverbial. Consider the simple present examples in (125):

| a. | Jan gaat | waarschijnlijk | zaterdag | dansen. | VP adverbial | |

| Jan goes | probably | Saturday | dance | |||

| 'Jan will probably go dancing on Saturday.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan gaat | zaterdag | waarschijnlijk | dansen. | clause adverbial | |

| Jan goes | Saturday | probably | dance | |||

| 'Jan will probably go dancing on Saturday.' | ||||||

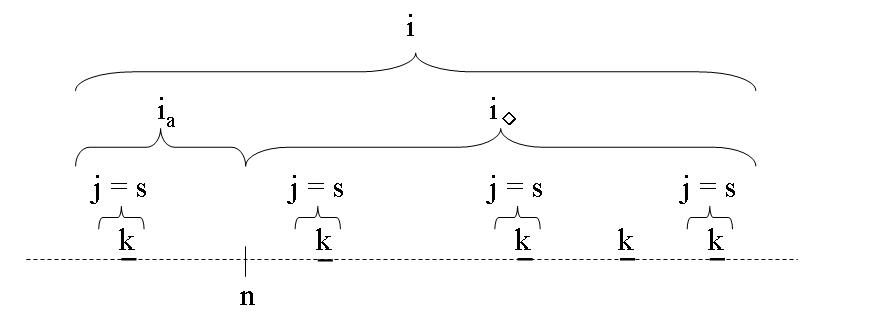

Many speakers consider these examples to be near-synonyms, since they both refer to a dancing event on Saturday, but the semantic representations assigned to them under our current assumptions are quite different. In (125a) the present j of k is simply assigned the default reading, according to which it is identical to present-tense interval i; for pragmatic reasons, eventuality k is located in the non-actualized part i◊ of this interval and thus on the first Saturday after speech time n; cf. representation (126a). The interpretation in (126b) is more indirect: the present j of k is first restricted to the first Saturday in i◊, and then eventuality k is located in this restricted time interval; cf. representation (126b). Note that the continuous line below k refers to the time interval to which Saturday refers in (126a), but in (126b) it refers to the duration of k.

| a. | VP adverbial |

|

| b. | Clause adverbial |

|

The difference in meaning can be highlighted by means of the scope paraphrases introduced for the detection of clause adverbials. While (125a) can be paraphrased as Het is waarschijnlijk zo dat Jan zaterdag gaat dansenIt is probably the case that Jan will go dancing on Saturday, example (125b) can be paraphrased as Het is zaterdag waarschijnlijk zo dat Jan gaat dansenOn Saturday it is probably the case that Jan will go dancing. The difference in meaning becomes even more obvious in examples such as (127) with the frequency adverb altijdalways.

| a. | Jan gaat | altijd | op zaterdag | dansen. | VP adverbial | |

| Jan goes | always | on Saturday | dance | |||

| 'Jan always goes dancing on a Saturday.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan gaat | op zaterdag | altijd | dansen. | clause adverbial | |

| Jan goes | on Saturday | always | dance | |||

| 'Jan always goes dancing on Saturdays.' | ||||||

Frequency adverbs such as altijdalways express that we are dealing with a recurring eventuality k in present/past-tense interval i. The VP adverbial op zaterdagon a Saturday in (127a) provides more precise information about the locations of k; it indicates that k occurs only (but not necessarily) on Saturdays, as in representation (128a), where s stands for Saturday. The clause adverbial op zaterdagon Saturdays in (127b), on the other hand, indicates that it is an inherent property of Saturdays that k occurs (although it may also occur elsewhere); cf. (128b).

| a. | VP adverbial |

|

| b. | Clause adverbial |

|

Representation (128a) also shows that it is not necessary for k to occur on every Saturday for (127a) to be true, which is necessary for example (127b) to be true. Representation (128b) also shows that (127b) allows k to occur on other days, which would make (127a) false. This suggests that the examples actually express material implications: example (127a) can be paraphrased by (129a), while (127b) can be paraphrased by (129b).

| a. | If Jan goes dancing, it is a Saturday. |

| b. | If/Whenever it is a Saturday, Jan goes dancing. |

This section has discussed a number of phenomena that find a natural account within the binary tense approach. Since temporal modification is still a relatively unexplored area in tense theory, we must leave it to future research to investigate the extent to which binary tense theory can be exploited in this area (although the reader may find some more information on this in Section 1.5.4). Subsection III now continues by showing that clauses with two locational adverbials can receive a similar account as clauses with two temporal adverbials.

This subsection discusses the semantic contribution of locational adverbials to the meaning of the clause. Again, we adopt the standard assumption from Section 8.2.1 that VP adverbials are modifiers of the proposition expressed by the lexical projection of the verb. In terms of tense representations like those given in Figure 1 and Figure 2, this amounts to saying that VP adverbials are modifiers of eventuality k. This claim is obviously true for example (130a), which simply locates the eventuality of Jan staying in a hotel in the present-tense interval i. However, it is less clear what the semantic contribution of the clause adverbial in Amsterdam in (130b) is.

| a. | Jan verblijft | (waarschijnlijk) | in een hotel. | |

| Jan lodges | probably | in a hotel | ||

| 'Jan is (probably) staying in a hotel.' | ||||

| b. | Jan verblijft | in Amsterdam | (waarschijnlijk) | in een hotel. | |

| Jan lodges | in Amsterdam | probably | in a hotel | ||

| 'Jan is (probably) staying in a hotel in Amsterdam.' | |||||

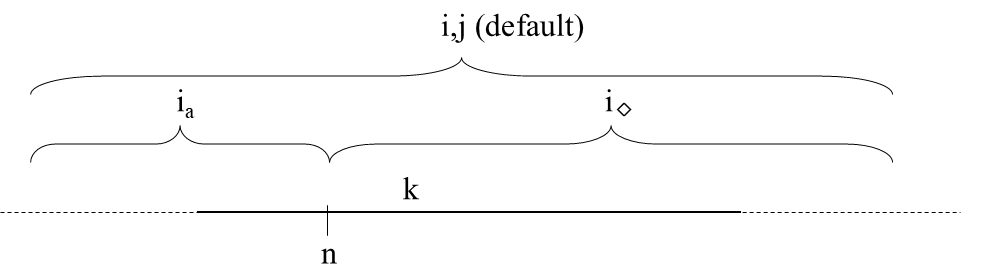

Suppose that the sentences in (130) are used in a conversation about Jan, who is currently on vacation. The default reading of example (130a) would then be that the eventuality of Jan staying in a hotel occurs at speech time n, as depicted in (131): the present j of k is taken to be identical to the present-tense interval i, and k is taken to co-occur with speech time n.

|

Example (130b) would instead express that the eventuality of Jan staying in a hotel is restricted to the period in which he is visiting Amsterdam. This can be accounted for by assuming that the locational clause adverbial overrides the default interpretation in the same way as a temporal clause adverbial, namely by restricting the present j of the eventuality. This is shown in representation (132), where k is the eventuality of Jan being on vacation and k' is the eventuality of Jan staying in a hotel.

|

The discussion above has shown that locational and temporal adverbials are similar in that they modify the eventuality k when they are used as VP adverbials, but the present j of k when they are used as clause adverbials. As with temporal adverbials, the two uses of locational adverbials are not always easy to distinguish. Consider the examples in (133).

| a. | Jan gaat | waarschijnlijk | in Amsterdam dansen. | VP adverbial | |

| Jan goes | probably | in Amsterdam dance | |||

| 'Jan will probably go dancing in Amsterdam.' | |||||

| b. | Jan gaat in Amsterdam waarschijnlijk | dansen. | clause adverbial | |

| Jan goes in Amsterdam probably | dance | |||

| 'Jan will probably go dancing in Amsterdam.' | ||||

Many speakers consider these examples to be near-synonyms, since they both refer to a dancing event in Amsterdam, but the semantic representations assigned to them under our current assumptions are quite different. In (133a), the present j of k is simply assigned the default reading according to which it is identical to present-tense interval i. For pragmatic reasons, eventuality k is located in the non-actualized part i◊ of this interval; cf. representation (134a), which is essentially the same as (126a). The interpretation in (133b) is more indirect: the present j of k is first restricted to the first occasion in i◊ that Jan will be in Amsterdam, and then eventuality k is located in this restricted time interval; cf. representation (134b), which is essentially the same as (126b).

| a. | VP adverbial |

|

| b. | Clause adverbial |

|

The difference in meaning can also be seen in the scope paraphrases. While (133a) can be paraphrased as Het is waarschijnlijk zo dat Jan in Amsterdam gaat dansenIt is probably the case that Jan will go dancing in Amsterdam, example (133b) can be paraphrased as Het is in Amsterdam waarschijnlijk zo dat Jan gaat dansenIn Amsterdam it is probably the case that Jan will go dancing. The difference in meaning again becomes more conspicuous in examples such as (135) with the frequency adverb altijdalways.

| a. | Jan gaat | altijd | in Amsterdam dansen. | VP adverbial | |

| Jan goes | always | in Amsterdam dance | |||

| 'Jan always goes dancing in Amsterdam.' | |||||

| b. | Jan | gaat in Amsterdam altijd | dansen. | clause adverbial | |

| Jan | goes in Amsterdam always | dance | |||

| 'Jan always goes dancing in Amsterdam.' | |||||

The frequency adverb altijd is used to express that we are dealing with a recurring eventuality k in the present/past-tense interval i. The VP adverbial in Amsterdam in (135a) provides more precise information about the location of k; it indicates that k only (but not necessarily) takes place in Amsterdam, as in representation (136a), where A stands for in Amsterdam. The clause adverbial in Amsterdam in (135b), on the other hand, indicates that it is an inherent (but not exclusive) property of Jan’s visits to Amsterdam that k occurs; cf. (136b).

| a. | VP adverbial |

|

| b. | Clause adverbial |

|

Representation (136a) also shows that it is not necessary for k to occur on every occasion that Jan is in Amsterdam for (135a) to be true, while this is needed to make example (135b) true. Representation (136b) further shows that (135b) allows k to also occur in other places, while this would make (135a) false. This suggests that the examples actually express material implications: example (135a) can be paraphrased by (137a), while (135b) can be paraphrased by (137b).

| a. | If Jan goes dancing, he is in Amsterdam. |

| b. | If/Whenever Jan is in Amsterdam, he goes dancing. |

The discussion above has shown that locational clause adverbials have more or less the same semantic impact as temporal clause adverbials. Locational and temporal clause adverbials can also co-occur. The examples in (138a&b) are simply repeated from above, showing that op zaterdag and in Amsterdam can both be used as clause adverbials; example (138c) shows that the two can also be combined. Examples such as (138c) can be seen as material implications with two conditions, (P & Q) → R: “if Jan is in Amsterdam and if it is Saturday, Jan goes dancing”.

| a. | Jan gaat | op zaterdag | altijd | dansen. | |

| Jan goes | on Saturday | always | dance | ||

| 'Jan always goes dancing on Saturdays.' | |||||

| b. | Jan gaat in Amsterdam altijd | dansen. | |

| Jan goes in Amsterdam always | dance | ||

| 'Jan always goes dancing in Amsterdam.' | |||

| c. | Jan gaat | in Amsterdam | op zaterdag | altijd | dansen. | |

| Jan goes | in Amsterdam | on Saturday | always | dance | ||

| 'Jan always goes dancing in Amsterdam on Saturdays.' | ||||||

The previous subsections have shown that clauses with multiple temporal/locational adverbial phrases find a natural accommodation and explanation in binary tense theory: used as VP adverbials, they modify the eventuality expressed by the lexical domain of the clause; used as clause adverbials, they modify the present of that eventuality. We have seen that the difference between the resulting interpretations can be made more prominent in the presence of the frequency adverb altijd; the interpretation can then be paraphrased by means of material implications, as illustrated by the example in (139), repeated from Subsection II.

| a. | Jan gaat | altijd | op zaterdag dansen. | VP adverbial | |

| Jan goes | always | on Saturday dance | |||

| 'Jan always goes dancing on a Saturday.' | |||||

| a'. | If Jan goes dancing, it is a Saturday. |

| b. | Jan | gaat op zaterdag altijd | dansen. | clause adverbial | |

| Jan | goes on Saturday always | dance | |||

| 'Jan will probably go dancing on Saturdays.' | |||||

| b'. | If it is a Saturday, Jan goes dancing. |

We like to note that a similar semantic effect was found in Section A28.3, sub III, with respect to the distribution of supplementives. This would suggest that our proposal for temporal and locational adverbials could be extended to other adverbials and adjuncts in general. Since this proposal opens up a new research program, we leave this matter for future research.