- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section discusses the semantics of spatial adpositions. Subsection I begins with a brief discussion of the central semantic notions of (change of) location and direction. Subsection II shows that spatial adpositions can be interpreted in three different ways, which we will refer to as deictic, inherent and absolute. Subsections III and IV argue that the mathematical notion of a vector is a very useful tool for properly describing the semantics of spatial adpositions. Finally, Subsection V delves a bit more deeply into the notion of path, which is crucial for the semantic description of directional PPs.

Spatial adpositions such as opon can often be used in two different contexts. This is clear from the fact that example (165a) is ambiguous between two readings: in the first reading, Jan is on the table and jumps there; in the second reading, Jan performs the action of jumping, as a result of which he ends up in a different location, namely on the table. The ambiguity of (165a) is resolved if the clause is in the perfect tense: if the auxiliary hebben is used, as in (165b), only the first reading survives; if the auxiliary zijn is used, as in (165c), only the second reading survives.

| a. | Jan springt | op | de tafel. | location or change of location | |

| Jan jumps | on(to) | the table |

| b. | Jan heeft | op | de tafel | gesprongen. | location | |

| Jan has | on | the table | jumped |

| c. | Jan is | op | de tafel | gesprongen. | change of location | |

| Jan has | onto | the table | jumped |

It is sometimes claimed that the two different readings are due to the adposition op itself, i.e. that we are dealing with two homonymous adpositions denoting a location and a change of location, respectively. We will not adopt this position, but assume instead that the specific interpretation of the adposition is due to the verb used: if springen selects the auxiliary hebben, it is used as an atelic verb, and thus no change of location is implied; if springen selects zijn, it is used as a telic verb, and thus a change of location is implied. This would be consistent with the fact, illustrated in (166), that most spatial PPs can be used as complements of location verbs, like liggento lie and staanto stand, and of change-of-location verbs, like leggen and zettento put. This shows that adpositions of the type in (166) are compatible with both the location and the change-of-location reading.

| a. | De lamp staat | bij/naast/onder/op | de tafel. | location | |

| the lamp stands | near/next.to/under/on | the table | |||

| 'The lamp stands near/next to/under/on the table.' | |||||

| a'. | De ladder | ligt | achter/langs/tegen | de muur. | |

| the ladder | lies | behind/along/against | the wall | ||

| 'The ladder is lies behind/along/against the wall.' | |||||

| b. | Jan zet | de lamp | bij/naast/onder/op | de tafel. | change of location | |

| Jan puts | the lamp | near/next.to/under/on | the table | |||

| 'Jan puts the lamp near/next to/under/on the table.' | ||||||

| b'. | Jan legt | de ladder | achter/langs/tegen | de muur. | |

| Jan puts | the ladder | behind/along/against | the wall | ||

| 'Jan puts the ladder behind/along/against the wall.' | |||||

A small number of spatial adpositions are special in that they cannot occur as complements of verbs of (change of) location. Such adpositions intrinsically denote a path (cf. Subsection V); since this notion plays a crucial role in our definition of the notion of direction as “movement along a path”, we will refer to such adpositions as directional adpositions. Directional PPs typically occur as the complement of verbs of traversing (which denote movement along a certain path), such as rijdento drive. Example (167) illustrates this for the preposition naarto.

| Jan | rijdt | naar Groningen. | direction | ||

| Jan | drives | to Groningen | |||

| 'Jan is driving to Groningen.' | |||||

Since the examples in (166) show that the difference between the location and change-of-location readings of the spatial adpositions is due to their syntactic environment (here: the verb), we can assume that spatial PPs headed by non-directional spatial adpositions simply refer to some point or area in space. Therefore, we will simply use the term locational adposition for such non-directional spatial adpositions.

The basic semantic contribution of the locational adpositions is that they establish a spatial relation between two entities. For example, the locational prepositional phrase in het huisin the house in (168) locates the subject of the clause Jan in space, which we can therefore call the located object (other terms found in the literature on spatial relations are theme, figure, and trajectory). More precisely, the located object is situated in space with respect to the complement of the preposition het huisthe house, which we can therefore call the reference object (other terms found in the literature are ground and landmark). The exact nature of the spatial relation is determined by the lexical meaning of the locational preposition inin; this relation would have been different if we had used voorin front of instead of in. Therefore, as a first approximation, it seems reasonable to consider the preposition in as a two-place predicate, and to assign the meaning in (168b) to the clause in (168a).

| a. | Jan is in het huis. | |

| Jan is in the house |

| b. | in (Jan, het huis) |

The assignment of meaning to the clause in (168a) seems rather straightforward: Jan is located in the house. In some cases, however, things are not so simple. There are actually three different ways of interpreting locational prepositions; they will be discussed in the following subsections.

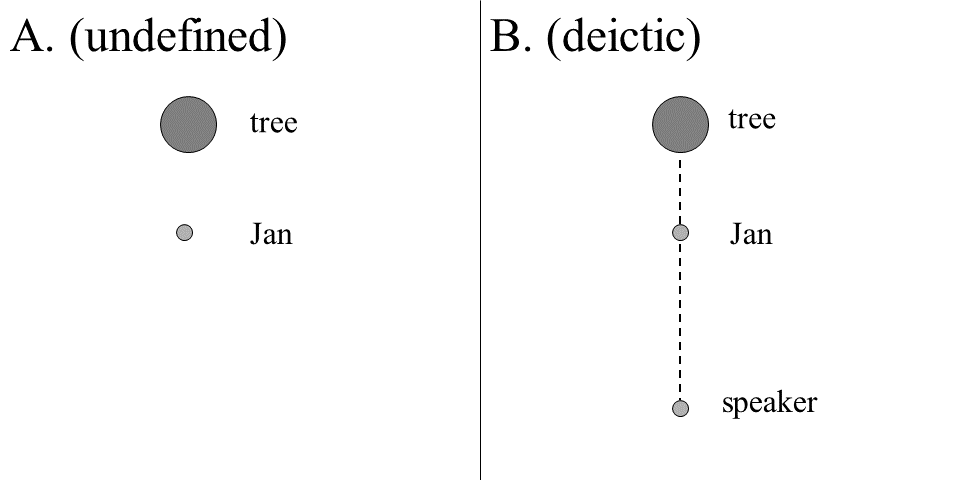

Consider example (169a). Assigning the semantic representation in (169b) to this example seems to miss the point somehow; cf. Subsection B for an account of this. This representation establishes a relation between the located and the reference object, but an additional third participant seems to be involved: a speaker uttering (169a) seems to compute the position of Jan in relation to both the reference object, i.e. the tree, and his own location.

| a. | Jan staat | voor | de boom. | |

| Jan stands | in.front.of | the tree |

| b. | voor (Jan, de boom) |

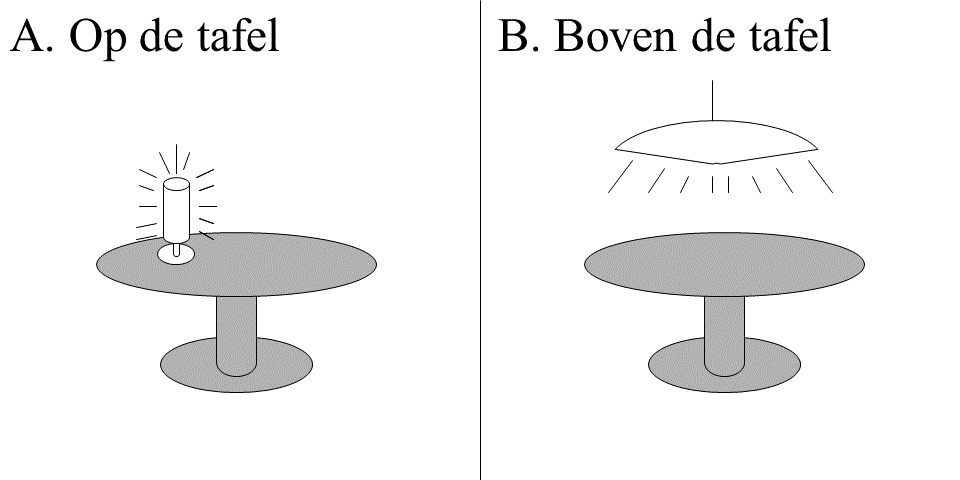

This means that example (169a) refers to the situation in Figure 1B; the situation in Figure 1A seems undefined.

The interpretation in Figure 1B, which depends on an additional anchoring point that is included in the computation of the location of the located object, is called deictic. When an adpositional phrase is interpreted deictically, this is indicated in the semantic representation by a D in superscript on the adpositional predicate: PD (x,y). The choice of an anchoring point z is represented as follows: PD,z (x,y). Example (169a), i.e. the situation depicted in Figure 1B, can thus be represented as in (170), where D,s indicates that we are dealing with a deictic interpretation of the preposition voor with the speaker s as its anchoring point.

| voorD,s (Jan, de boom) |

However, the examples in (171) show that the anchoring point need not be the speaker. In (171a) the anchoring point is the addressee a, and in (171b) it is some other participant in the discourse, viz. de kerkthe church. The corresponding semantic representations are given in the primed examples.

| a. | Vanuit | jou | gezien, | staat | Jan recht | voor de boom. | |

| from | you | seen | stands | Jan straight | in.front.of the tree | ||

| 'Seen from your position, Jan is standing right in front of the tree.' | |||||||

| a'. | voorD,a (Jan, de boom) |

| b. | Vanuit | de kerk | gezien, | staat | Jan recht | voor de boom. | |

| from | the church | seen | stands | Jan straight | in.front.of the tree | ||

| 'Seen from the church, Jan is standing right in front of the tree.' | |||||||

| b'. | voorD,de kerk (Jan, de boom) |

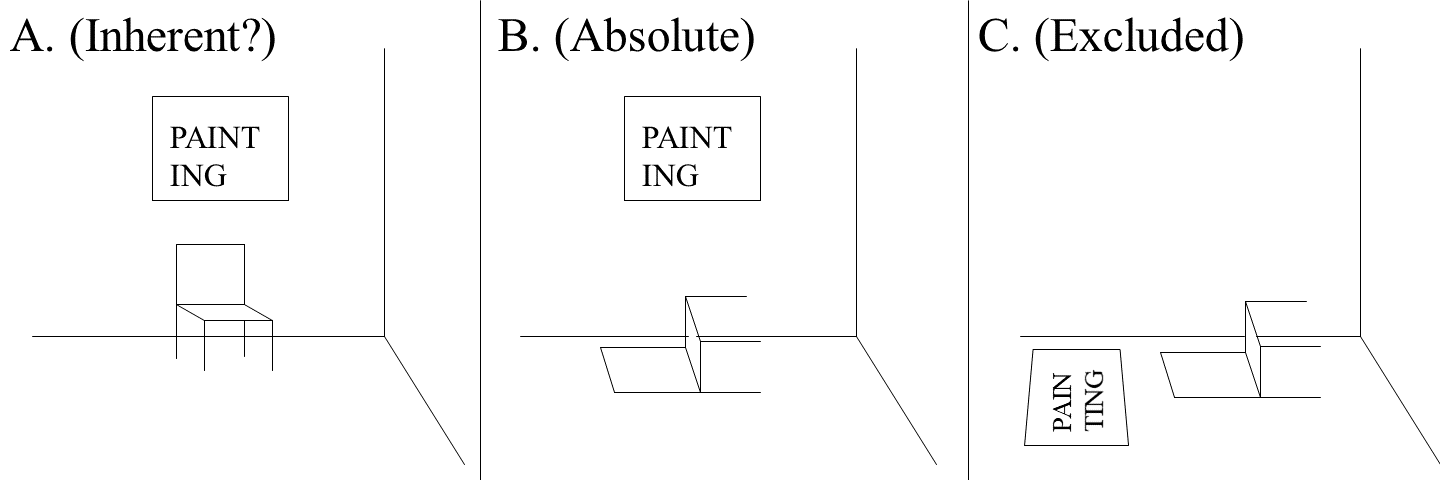

The anchoring point from which the location of the located object is computed can also be the reference object itself (i.e. the referent of the nominal complement of the adposition). This is only possible if the reference object is structured in terms of the relevant dimension(s). Consider example (172a), which can be represented as in Figure 2A, where the location of Jan is computed by taking the reference object as the anchoring point; the speaker’s position relative to Jan and the car is not relevant. The difference between (169a) and (172a) has to do with the dimensional structuring of the reference object; a car can be seen as an object with a back and a front (indicated in Figure 2A by an arrow through the object), whereas we do not normally perceive trees in this way. Because of the different dimensional properties of cars and trees, we can take the former but not the latter as the anchoring point for the preposition voor. The interpretation of locational adpositions in which we take the reference object as the anchoring point is called inherent and is indicated by the capital letter I in superscript on the adpositional predicate: PI. Thus, on the inherent interpretation, example (172a) can be represented as in (172b). Note that the deictic interpretation is also often possible; (172a) can also refer to the situation depicted in Figure 2B, to which the semantic representation in (172c) can be assigned.

| a. | Jan staat | voor | de auto. | |

| Jan stands | in.front.of | the car | ||

| 'Jan is standing in front of the car.' | ||||

| b. | voorI (Jan, de auto) |

| c. | voorD,s (Jan, de auto) |

The deictic and the inherent interpretations of adpositional phrases differ in their logical properties. This is illustrated by the examples in (173).

| a. | De auto | staat | voor | de kerk. | AND | |

| the car | stands | in.front.of | the church |

| b. | Jan staat | voor | de auto. | ⇏ | |

| Jan stands | in.front.of | the car |

| c. | Jan staat | voor | de kerk. | |

| Jan stands | in.front.of | the church |

If we interpret the adpositions deictically, we can infer (173c) from (173a&b); cf. Figure 3A. But if we interpret the adpositions inherently, the inference is no longer valid; cf. Figure 3B. The same difference in logical properties applies to other adpositions that can be used both deictically and inherently, like the prepositions achterbehind, naastnext to and the phrasal prepositions links/rechts vanto the left/right of.

Similar inferences are also invalid when we switch from one perspective to another. The preposition in in (174a) is inherent, whereas the preposition voor in (174b) is interpreted deictically; cf. Figure 1. From these two examples, we cannot conclude that (174c) is true: for example, if Jan is standing in front of the tree trunk and the bird is in the top of the tree, (174c) is clearly false.

| a. | De vogel | zit | in de boom. | ##AND | ||

| the bird | sits | in the tree | AND | |||

| 'The bird is (up) the tree.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan staat | voor | de boom. | ⇏ | |

| Jan stands | in.front.of | the tree | |||

| 'Jan is in front of the tree.' | |||||

| c. | Jan staat | voor | de vogel. | |

| Jan stands | in.front.of | the bird | ||

| 'Jan is in front of the bird' | ||||

Consider example (175a) below, which can be depicted as in Figure 4A. The fact that the computation of the location of the painting is independent of the speaker suggests that we are dealing with an inherent interpretation of the prepositional phrase boven de stoelabove the chair: bovenI (het schilderij, de stoel). This would be consistent with the fact that a chair can be considered to have a bottom and a top. However, there is reason to doubt that the dimensions of the chair are really involved in the computation: (175a) can also be used to refer to the situation in Figure 4B, where the configuration between the chair and the painting has been changed. Moreover, (175a) cannot be used to refer to the situation in Figure 4C, where the configuration between the chair and the painting is essentially the same as in Figure 4A, not even if we replace the verb hangen with liggento lie, which may provide a more appropriate description of the positioning of the painting.

| a. | Het schilderij | hangt | boven | de stoel. | |

| the painting | hangs | above | the chair | ||

| 'The painting is hanging above the chair.' | |||||

| b. | boven (het schilderij, de stoel) |

Interpretations of adpositional phrases that have neither an internal nor an external anchoring point are called absolute (i.e. depending only on the natural environment such as the surface of the earth); these interpretations are presented without a superscript on the adpositional predicate, as in (175b).

Locational adpositions locate an object in space with respect to the reference object. However, the interpretation of locational PPs is often rather vague. This is illustrated by the sentences in (176).

| a. | De fotograaf | staat | achter de camera. | |

| the photographer | stands | behind the camera | ||

| 'The photographer is standing behind the camera.' | ||||

| b. | De lampen | staan | achter de camera. | |

| the lamps | stand | behind the camera | ||

| 'The lamps are behind the camera.' | ||||

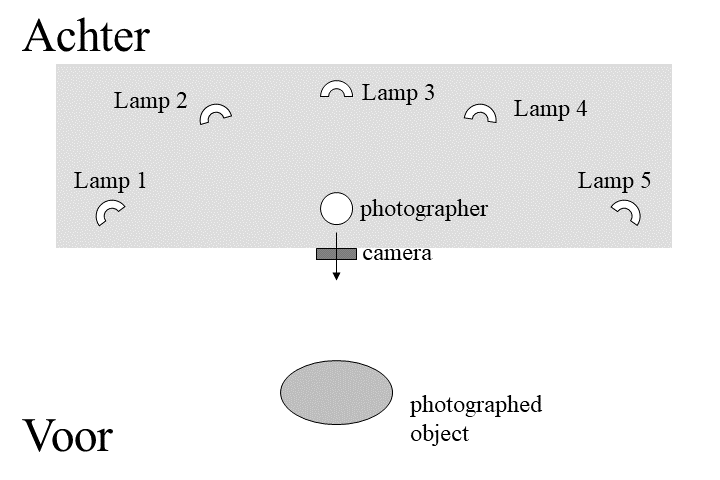

Example (176a) is usually interpreted to mean that the photographer is standing in the position shown in Figure 5. Example (176b), on the other hand, need not be interpreted to mean that all lamps are positioned like lamp 3; the positions of the other lamps are included, i.e. the only requirement is that they remain within the gray area.

Figure 5 shows that locational PPs may sometimes refer to rather large areas. As a result of this, the areas denoted by different locational adpositions can overlap. For example, if we want to refer specifically to lamp 1 in Figure 5, we could also say that it stands naastnext to or links vanto the left of the camera. We can even express the appropriateness of the chosen adpositions by means of examples such as (177), which makes it explicit that achterbehind and naast “next to’ are both applicable, but that naast is the more appropriate preposition for expressing the intended spatial relation.

| Lamp 1 | staat | meer naast | dan | achter de camera. | ||

| lamp 1 | stands | more next.to | than | behind the camera | ||

| 'Lamp 1 is situated more next to than behind the camera.' | ||||||

The positions in the area can be made even more specific by modifying the prepositional phrase. If we interpret the preposition achter deictically from the point of view of the photographed object, the statements in (178) are true. Note in passing that according to the inherent interpretation of achter, which takes the camera as its anchoring point, lamp 2 would be to the right of the camera.

| a. | Lamp 3 | staat | recht | achter de camera. | |

| lamp 3 | stands | straight | behind the camera | ||

| 'Lamp 3 is positioned straight behind the camera.' | |||||

| b. | Lamp 2 | staat | links | achter de camera. | |

| lamp 2 | stands | left | behind the camera | ||

| 'Lamp 2 is positioned to the left behind the camera.' | |||||

The examples in (178) give an indication of the direction we have to look in order to find the located object in question. As is shown in (179), the distance between the reference and the located object can also be indicated.

| a. | De fotograaf | staat | vlak | achter de camera. | |

| the photographer | stands | right | behind the camera | ||

| 'The photographer is standing right behind the camera.' | |||||

| b. | Lamp 3 | staat | vijf meter | achter de camera. | |

| lamp 3 | stands | five meters | behind the camera | ||

| 'Lamp 3 is positioned five meters behind the camera.' | |||||

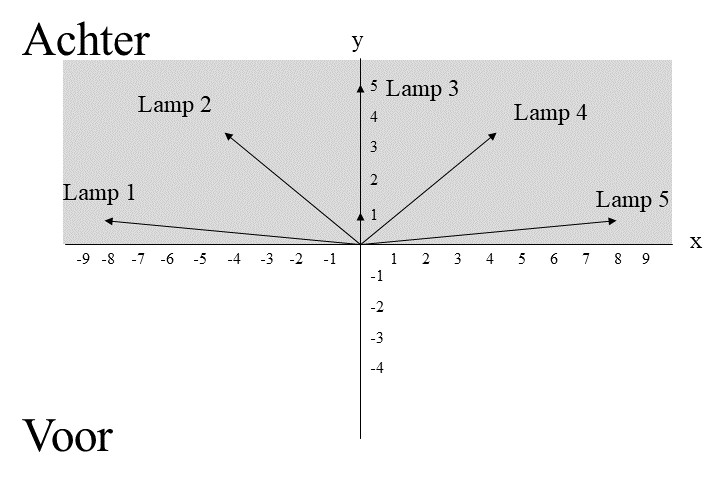

This means that each point in the area referred to by the locational PP achter de camera can be defined in terms of a direction and a distance. In other words, the preposition achter can be thought of as a set of vectors that project the position of the reference object onto a potential position of the located object. Consider Figure 6, where the reference object occupies the (0,0) position. The preposition achter denotes those vectors V‹x,y› that originate at (0,0), and for which y > 0. Since the vectors V‹-4,3›, V‹0,5› and V‹8,1› map the position of the reference object onto the positions of lamps 2, 3 and 5, respectively, the latter are indeed in the area referred to by the PP achter de camera.

We can also denote subsets of the set of vectors denoted by the PP achter de camerabehind the camera: the modified PP recht achter de camerastraight behind the camera denotes the subset of vectors denoted by achter with x = 0, the modified PP links achter de camera denotes the subset of vectors with x < 0, and the modified PP rechts achter de camera denotes the subset of vectors with x > 0. Furthermore, the modified PP vlak achter de camera denotes the subset of vectors that are smaller than some contextually determined magnitude (here, length). These examples show that the assumption that locational prepositions denote a set of vectors will be very useful in the discussion of the use of locational PPs as modifiers in Section 34.1. For now, however, it is sufficient to note that locational PPs refer to areas rather than fixed points in space.

Prepositions like achterbehind and bovenabove seem to express that the magnitude of the vector is greater than zero, i.e. that there is some distance between the reference object and the located object. However, some prepositions require that there should be physical contact between the two objects, i.e. they require that the magnitude of the vector is zero. This difference can be illustrated by the prepositions opon and bovenabove in (180); example (180a) implies that there is physical contact between the table and the lamp, as in Figure 7A, whereas (180b) suggests that there is no such contact, as in Figure 7B.

| a. | De lamp | staat | op de tafel. | |

| the lamp | stands | on the table | ||

| 'The lamp is standing on the table.' | ||||

| b. | De lamp | hangt | boven de tafel. | |

| the lamp | hangs | above the table | ||

| 'The lamp is hanging above the table.' | ||||

Note that the choice of verb does not affect the interpretation of the preposition; it is possible to replace staan with hangen in (180a) if we are referring to a situation like Figure 7B, where the lamp hangs so low that it touches the table. More common examples of this kind are given in (181).

| a. | De gordijnen | hangen | op de vensterbank. | |

| the curtains | hang | on the windowsill | ||

| 'The curtains are touching the windowsill.' | ||||

| b. | Je rok | hangt | op de grond. | |

| your skirt | hangs | on the floor | ||

| 'The hem of your skirt is touching the floor.' | ||||

The fact that the preposition op denotes the null vector, while boven denotes a larger set of vectors with a magnitude greater than 0, accounts for the fact that (under the idealization that the length of the part of the square adjacent to the church does not exceed the length of the side of the church adjacent to the square) the inference in (182) is valid, while the one in (183) is not.

| a. | Jan loopt | op het plein. | ##AND | ||

| Jan walks | on the square | AND | |||

| 'Jan is walking on the square.' | |||||

| b. | Het plein is voor de kerk. | ⇒ | |

| 'The square is in front of the church.' | |||

| c. | Jan loopt voor de kerk. | |

| 'Jan is walking in front of the church.' |

| a. | De luchtballon | zweeft | boven het plein. | ##AND | ||

| the air.balloon | floats | above the square | AND | |||

| 'The hot-air balloon is floating above the square.' | ||||||

| b. | Het plein is voor de kerk. | ⇏ | |

| 'The square is in front of the church.' | |||

| c. | De luchtballon zweeft voor de kerk. | |

| 'The hot-air balloon is floating in front of the church.' |

However, there is also a potential problem with the claim that the denotations of prepositions like achter and boven do not include the null vector. If we assume that the meaning of achter/boven op in (184) is compositionally determined, we should conclude that achter and boven are at least compatible with the null vector, since otherwise a contradiction would arise.

| a. | De productiedatum | staat | achter | op | het blik. | |

| the production.date | stands | behind | on | the can | ||

| 'The production date is on the back of the can.' | ||||||

| b. | De productiedatum | staat | boven | op | het blik. | |

| the production.date | stands | above | on | the can | ||

| 'The production date is on top of the can.' | ||||||

We will not discuss this problem here, but simply assume that the underlying hypothesis that the meanings of achter/boven op are compositionally determined is incorrect. Section 34.1.3 will show that formations like achterop and bovenop are compounds, and we therefore expect that the denotation of these formations consists of a subset of the denotation of the second member, the preposition op. Since the reference object het blik in (184) is not a point in space but a three-dimensional object, the preposition op can be assumed to denote a non-singleton set of null vectors which are located at different positions on the surface of the reference object. It is therefore correctly predicted that the compounds achterop and bovenop denote different subsets of the set of null vectors denoted by op.

Although the discussion of the examples in (184) clearly shows that, strictly speaking, this is not correct, we will often take the reference object to be a point in space instead of a physical object with three-dimensional extensions in order to simplify the following discussion. This is why we will usually refer to “the null vector” instead of “the set of null vectors”. The three-dimensional extensions of the reference object will be considered only when this is necessary for the discussion.

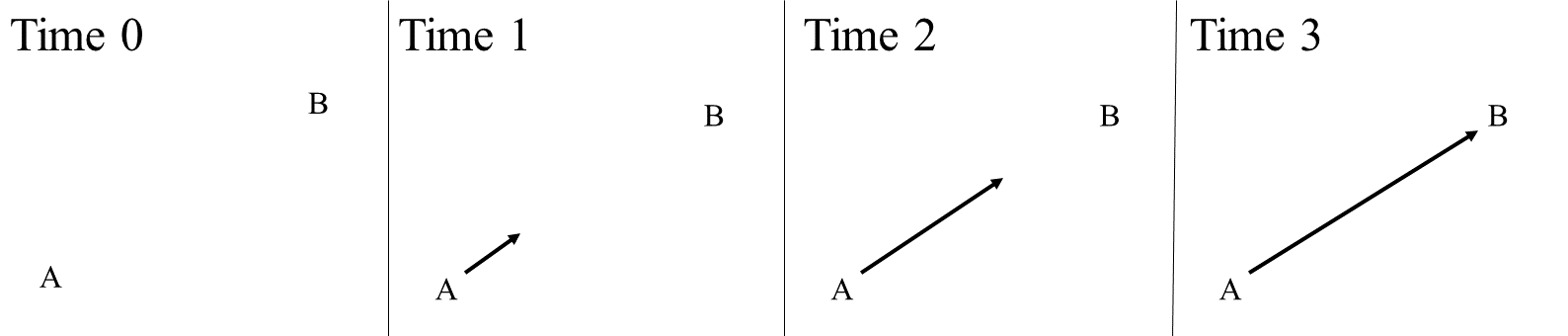

Directional adpositions differ from locational ones in that they do not situate the located object in a fixed position in space. As a result, the denotation of a directional preposition cannot simply be considered as a set of vectors. This does not mean, however, that the notion of vector is irrelevant in the case of directional PPs. Directional PPs express that the located object traverses a certain path. A path can be defined as an ordered set of vectors, each of which is associated with a particular position on the timeline. The path denoted by van A naar Bfrom A to B can then be represented as in Figure 8, which can be read as a cartoon. In our visual representations below, we will often indicate paths with a blocked or dotted arrow.

The situation depicted in Figure 8 is an appropriate characterization of the directional phrase in (185a), in which the PPs van Utrecht from Utrecht’ and naar Groningento Groningen act as complements of the verb of traversing rijdento drive. Besides this “core” directional reading, directional PPs can also have two slightly different readings. The PPs in (185b) do not denote a path that is traversed, but indicate the extent of the located object deze wegthe road; this example expresses that the road is situated on a path that goes from Utrecht to Groningen. We will refer to this use of the PP in (185b) as the extent reading (note that the verb lopen is also used as a verb of traversing meaning “to walk” when the subject is animate). Finally, the directional PP in (185c) is used with an orientation reading.

| a. | Jan rijdt | van Utrecht | naar Groningen. | directional reading | |

| Jan drives | from Utrecht | to Groningen |

| b. | Deze weg | loopt | van Utrecht | naar Groningen. | extent reading | |

| this road | goes | from Utrecht | to Groningen |

| c. | De richtingaanwijzer | wijst | naar Groningen. | orientation reading | |

| the direction.sign | points | to Groningen |

This subsection concludes our overview of the semantic concepts that will play a role in the semantic description of the various individual adpositions. The discussion is divided into four parts, corresponding to the syntactic classification based on the position of the nominal complement of the adposition.