- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section discusses the modification of absolute (i.e. non-scalar) adjectives. Subsection I begins with a brief discussion of some differences between scalar and absolute adjectives. Subsections II and III then discuss two different types of modifiers, which will be referred to as approximative and absolute modifiers.

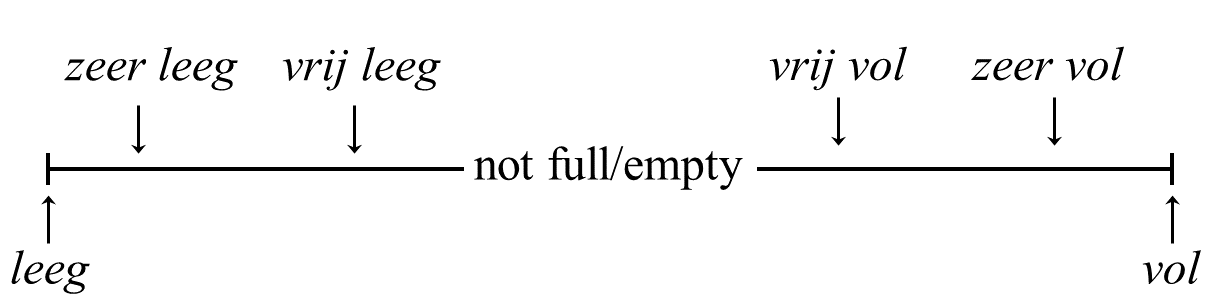

Section 25.1 has discussed the modification of scalar adjectives. The modifier is typically an amplifier such as zeervery or a downtoner such as vrijrather, which scale upward or downward from some tacitly assumed standard value or norm. To illustrate this, we repeat the graphical representation in (7) for the adjectives goedgood and slechtbad/evil as (264).

| Scale of goodness |

The representation in (264) makes it clear that the implications in (265) are valid; the adjective in (265a) is preceded by the amplifier zeer, and we can conclude from zeer A that A also holds; the adjective in (265b) is preceded by the downtoner vrij, and we can conclude from vrij A that A holds as well.

| a. | Dat boek is zeer goed/slecht. | ⇒ | |

| that book is very good/bad |

| a'. | Dat boek is goed/slecht. | |

| that book is good/bad |

| b. | Dat boek is vrij goed/slecht. | ⇒ | |

| that book is rather good/bad |

| b'. | Dat boek is goed/slecht. | |

| that book is good/bad |

The implication relations are quite different when the adjectives are absolute. Take the polar adjectives leegempty and volfull, which seem to refer to the boundaries of the scale in (266). The use of the modifiers vrij and zeer with these adjectives implies that we are referring to some point between the two boundaries.

| Scale of fullness |

|

The representation in (266) shows that in this case we cannot conclude from zeer/vrij A that A also holds; in fact, we must conclude that A does not hold.

| a. | De fles | is zeer | leeg/vol. | ⇒ | |

| the bottle | is very | empty/full |

| a'. | De fles | is niet | leeg/vol. | |

| the bottle | is not | empty/full |

| b. | De fles | is vrij | leeg/vol. | ⇒ | |

| the bottle | is rather | empty/full |

| b'. | De fles | is niet | leeg/vol. | |

| the bottle | is not | empty/full |

The sketch given above is an idealization of reality, since the adjective volfull can sometimes also be used as a scalar adjective. In everyday practice, vol is generally not used in the sense of “100% filled”; a cup of coffee would be called vol even if it were not filled to the brim (in fact, if it were, it would be considered too full). In this use of vol, we can conclude from the fact that zeer vol is applicable that vol is also applicable. For the sake of argument, however, we have assumed in our sketch that vol means “100% filled”.

The fact that the logical implications in (265) do not hold for absolute adjectives implies that semantic representations such as those in (8) from Section 25.1.2, repeated here as (268), cannot be used to express the semantic contribution of the modifiers of absolute adjectives.

| a. | Jan is zeer goed. | amplifier | |

| Jan is very good |

| a'. | ∃d [goed (Jan,d) & d > dn] |

| b. | Jan is vrij goed. | downtoner | |

| Jan is rather good |

| b'. | ∃d [goed (Jan,d) & d < dn] |

| c. | Jan is min of meer goed. | neutral | |

| Jan is more or less good |

| c'. | ∃d [goed (Jan,d) & d ≈ dn] |

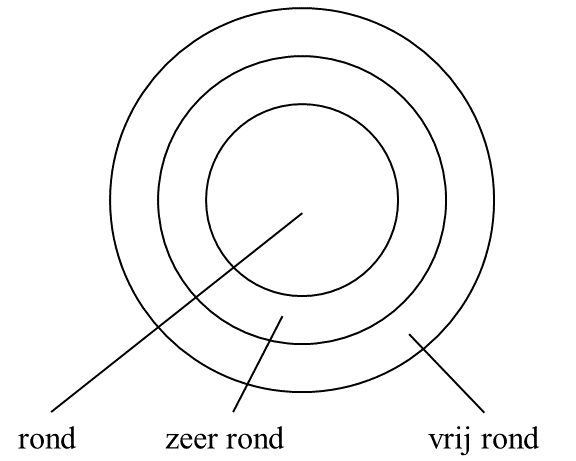

We conclude that modifiers of absolute adjectives do not refer to a degree on an implied scale; this is also supported by the fact that they can also be used with geometric adjectives, which do not involve scales at all. Just as vrij/zeer leeg in (267) implies that the bottle is not empty, vrij/zeer rondrather/very round in (269a) implies that the logical subject of the AP is not round; Jan’s face merely shows some resemblance to a round shape. This intuition can be represented as in (269b) by assuming that the modified APs denote certain mutually exclusive partitions of some larger set of entities. To avoid confusion, note that the circles in (269b) represent sets, not geometric shapes.

| a. | Jans gezicht | is vrij/zeer | rond. | ⇒ | |

| Jan’s face | is rather/very | round |

| a'. | Jans gezicht | is niet | rond. | |

| Jan’s face | is not | round |

| b. |  |

Something similar applies to color adjectives such as roodred. When the leaves of the trees change color in the fall, we can use the expressions in (270a) to indicate that some of the leaves have already changed color, or that the leaves are in the process of changing color. Similarly, we can use (270b) to indicate that Jan’s face is partly red.

| a. | De bladeren | zijn | al | vrij/zeer | rood. | |

| the leaves | are | already | rather/very | red |

| b. | Jans gezicht | is vrij/zeer | rood. | |

| Jan’s face | is rather/very | red |

What the examples in (267) to (270) have in common is that the modifiers indicate that the logical subject of the adjective A cannot be (fully) characterized as having the property denoted by A; it only has a property similar to it. However, the absolute adjectives can also be preceded by a modifier indicating that the property is applicable: examples with the modifier helemaalcompletely are given in (271).

| a. | De fles | is helemaal | leeg/vol. | ⇒ | |

| the bottle | is completely | empty/full |

| a'. | De fles | is leeg/vol. | |

| the bottle | is empty/full |

| b. | De tafel | is helemaal | rond. | ⇒ | |

| the table | is fully | round |

| b'. | De tafel | is rond. | |

| the table | is round |

| c. | De bladeren | zijn | helemaal rood | ⇒ | |

| the leaves | are | completely red |

| c'. | De bladeren | zijn | rood. | |

| the leaves | are | red |

From now on, we will call the modifiers with the properties of those in (267) through (270) approximative, and their counterparts in (271) absolute. These approximative and absolute modifiers will be discussed in Subsections II and III.

Many approximative modifiers indicate that the property denoted by the adjective is almost or nearly applicable. Some examples involving adverbs are given in (272).

| a. | een | bijna | perfect artikel | |

| an | almost | perfect article |

| b. | een | nagenoeg | onmogelijke | taak | |

| an | almost | impossible | task |

| c. | een | praktisch | dode | hond | |

| a | virtually | dead | dog |

| d. | een | vrijwel | dove | man | |

| a | nearly | deaf | man |

Occasionally more complex phrases are used, such as zo goed alsas good as in (273a); the expression op sterven na dood in (273b) is idiomatic.

| a. | Opa | is zo goed als | blind. | |

| grandpa | is as good as | blind | ||

| 'Grandpa is practically blind.' | ||||

| b. | De hond | is op | sterven | na | dood. | |

| the dog | is OP | die | NA | dead | ||

| 'The dog is on the verge of death.' | ||||||

The examples in (274) show that approximatives cannot usually be combined with scalar adjectives. The only exceptions are modifiers like vrijrather and zeervery, which can be used both as degree modifiers and as approximative modifiers; cf. Subsection I for examples.

| a. | * | een | bijna | interessant | artikel |

| an | almost | interesting | article |

| b. | * | een | nagenoeg | moeilijke | taak |

| an | almost | difficult | task |

| c. | * | een | praktisch | lieve | hond |

| a | virtually | friendly | dog |

| d. | * | een | vrijwel | slechthorende | man |

| a | nearly | hard-of-hearing | man |

Possible exceptions to this general rule are given in (275), where the approximative modifier bijnanearly indicates that the gradable adjective is more or less appropriate. However, these examples are difficult to judge because bijna can also be used as a clause adverbial, as can be seen from the fact that topicalization of the adjective alone (also) seems possible.

| a. | Dit gedrag | is | bijna | kinderlijk. | |

| this behavior | is | almost | childlike |

| a'. | <Bijna> kinderlijk is dit gedrag <?bijna>. |

| b. | Jan was bijna | boos. | |

| Jan was almost | angry |

| b'. | <??Bijna> boos was Jan <bijna>. |

Note that goedgood, which was given above as a scalar adjective, can also be used as an absolute adjective, in which case it means “correct” and stands in opposition to the adjective foutwrong. Example (276) is therefore not a counterexample to the claim that approximatives cannot be combined with scalar adjectives, because here goed can only be interpreted as “correct”.

| Je antwoord | is bijna | goed. | ||

| your answer | is almost | correct |

The approximatives in (272) indicate that the adjective is “close” to being appropriate. With the modifiers in (277), the implied “distance” seems greater, but remains relatively vague.

| a. | De fles | is zo’n beetje | leeg. | |

| the bottle | is more or less | empty |

| b. | De fles | is min of meer | leeg. | |

| the bottle | is more or less | empty |

This vagueness does not arise with the modifiers in (278), which indicate quite precisely what the “distance” is.

| a. | De fles | is half leeg. | |

| the bottle | is half empty |

| b. | De fles | is voor driekwart | leeg. | |

| the bottle | is for three.quarters | empty | ||

| 'The bottle is three-quarters empty.' | ||||

Occasionally, approximatives may themselves be modified by an adverb like alalready or nogstill. These adverbs indicate that the entity modified by the approximative is changing: al indicates that it is moving “closer” to the property denoted by the adjective, while nog indicates that it is moving in the opposite direction. When drinking wine, the speaker can use the primeless but not the primed version in (279) because he is in the process of emptying bottles; when bottling wine, on the other hand, only the primed examples would be appropriate.

| a. | Deze fles | is nog | vrijwel/half | vol. | |

| this bottle | is still | nearly/half | full |

| a'. | Deze fles | is al | vrijwel/half | vol. | |

| this bottle | is already | nearly/half | full |

| b. | Deze fles | is al | bijna/half | leeg. | |

| this bottle | is already | nearly/half | empty |

| b'. | Deze fles | is nog | bijna/half | leeg. | |

| this bottle | is still | nearly/half | empty |

As a rule, approximative modifiers do not occur in negative clauses: examples such as (280) are acceptable only if they are used to revoke an assumption held by or attributed to the addressee. In this respect, approximatives are very different from absolute modifiers; cf. example (285) in Subsection III.

| a. | Deze fles | is niet | vrijwel | vol/leeg. | |

| this bottle | is not | nearly | full/empty |

| b. | Deze fles | is niet | bijna | vol/leeg. | |

| this bottle | is not | nearly | full/empty |

| c. | Deze fles | is niet | half | vol/leeg. | |

| this bottle | is not | half | full/empty |

The examples in (281) deserve special mention. The approximative modifier vrijwel in (281a) modifies the negative adverb niet, which in turn modifies the scalar antonym versnedendiluted of the absolute adjective puur/onversnedenclean/undiluted. It is as if the combination niet versneden behaves like a complex absolute adjective on a par with puur/onversneden. In (281b), the modifier nauwelijkshardly is negative in itself and seems to act as a kind of approximative modifier: nauwelijks versneden is more or less synonymous with vrijwel puuralmost clean. Examples (281c&d) show that the modifier nauwelijks cannot usually be combined with absolute adjectives such as puurneat, nor with scalar adjectives without an absolute antonym such as lekkertasty.

| a. | De wijn | bleek | vrijwel | niet | versneden. | |

| the wine | turned.out | almost | not | diluted |

| b. | De wijn | bleek | nauwelijks | versneden. | |

| the wine | turned.out | hardly | diluted |

| c. | * | De wijn | bleek | nauwelijks | puur/onversneden. |

| the wine | turned.out | hardly | neat/undiluted |

| d. | * | De wijn | bleek | nauwelijks | lekker. |

| the wine | turned.out | hardly | tasty |

Finally, note that approximative modifiers cannot be combined with intrinsically amplified absolute adjectives, such as eivol/bomvolcrammed-full and kurkdroogbone-dry, in which the first morpheme emphasizes the fact that the property denoted by the adjective applies in full. This is illustrated in (282); we also refer the reader to the discussion of example (36) in Section 25.1.2, sub IE, and example (286) in Subsection III below.

| a. | *? | een | vrijwel | bomvolle | zaal |

| an | almost | crammed-full | hall |

| b. | *? | een | nagenoeg | kurkdroge | doek |

| a | virtually | bone.dry | cloth |

Absolute modifiers indicate that the property denoted by the adjective applies in full. Some examples are given in the primeless examples of (283). The primed examples show that absolute modifiers, like approximatives, cannot modify scalar adjectives.

| a. | een | geheel | volle | zaal | |

| a | completely | full | hall |

| a'. | * | een | geheel | grote | zaal |

| a | completely | beautiful | hall |

| b. | een | helemaal | lege | fles | |

| a | completely | empty | bottle |

| b'. | * | een | helemaal | mooie | fles |

| a | completely | beautiful | bottle |

| c. | een | totaal | overbodig | boek | |

| a | totally | superfluous | book |

| c'. | *? | een | totaal | saai | boek |

| a | totally | boring | book |

| d. | een | volkomen | ronde | tafel | |

| a | perfectly | round | table |

| d'. | *? | een | volkomen | gezellige | tafel |

| a | perfectly | cozy | table |

| e. | een | volledig | droge | doek | |

| a | totally | dry | cloth |

| e'. | *? | een | volledig | zachte | doek |

| a | totally | soft | cloth |

Like approximatives, absolute modifiers can be modified by adverbs like alalready and nogstill; al indicates that the logical subject of the modified AP has completed a process of change, as a result of which the adjective has become appropriate; nog indicates that a process of change is expected but has not yet begun, as a result of which the adjective is still appropriate. If the speaker is drinking wine, he can use the primeless but not the primed examples in (284) because he is in the process of emptying bottles; if the speaker is bottling wine, on the other hand, only the primed examples would be appropriate.

| a. | Deze fles | is nog | helemaal | vol. | |

| this bottle | is still | completely | full |

| a'. | Deze fles | is al | helemaal | vol. | |

| this bottle | is already | completely | full |

| b. | Deze fles | is al | helemaal | leeg. | |

| this bottle | is already | completely | empty |

| b'. | Deze fles | is nog | helemaal | leeg. | |

| this bottle | is still | completely | empty |

Unlike approximative modifiers, absolute modifiers are possible in negative clauses; cf. example (280). Note that when the element meer is added, as in (285b), it is implied that the property denoted by the adjective was applicable at some earlier time. In this respect, niet ... meer acts as the antonym of al in (284).

| a. | Deze fles | is niet | helemaal | vol/leeg. | |

| this bottle | is not | completely | full/empty |

| b. | Deze fles | is niet helemaal | vol | meer. | |

| this bottle | is not completely | full | anymore | ||

| 'This bottle is not full anymore.' | |||||

The examples in (286) show that absolute modifiers are like approximative modifiers in that they cannot be used with intrinsically amplified absolute adjectives like eivol/bomvolcrammed-full and kurkdroogbone-dry. This is because the first morpheme already indicates that the property denoted by the adjective applies in full.

| a. | *? | een | helemaal | bomvolle | zaal |

| a | completely | crammed-full | hall |

| b. | *? | een | volledig | kurkdroge | doek |

| a | fully | bone.dry | cloth |