- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Sections 2.1.2 and 2.1.3 have discussed the so-called unaccusative verbs, i.e. verbs that take an internal theme argument that appears as the subject of the clause. The derived subjects of these verbs have a thematic role similar to that of the direct object of a (di)transitive clause and behave in several respects like the subjects of passive constructions. This section will argue that there is also a class of undative main verbs which head constructions in which the derived subject corresponds to an indirect object in a ditransitive clause. Subsection I begins with a discussion of some properties of the verb krijgento get, which we take to be a prototypical instantiation of the class of undative verbs. Subsection II discusses the verbs hebbento have and houdento keep, which can be seen as the non-dynamic counterparts of the dynamic undative verb krijgen. Finally, Subsection III considers a number of other verbs that may belong to the class of undative verbs.

This subsection argues that the verb krijgento get can be seen as an instantiation of the class of undative verbs. Consider the examples in (142). The subject in (142b) has a thematic role similar to that of the indirect object of gevento give in (142a): in both cases we seem to be dealing with a recipient argument. This suggests (i) that the verb krijgento get has no external argument (although the agent/cause argument of the ditransitive verb can be expressed in a van-PP) and (ii) that the subject in (142b) is a derived one, which will be referred to as recipient-subject.

| a. | Jan gaf | Marie een boek. | |

| Jan gave | Marie a book |

| b. | Marie kreeg | een boek | (van Jan). | |

| Marie got | a book | of Jan | ||

| 'Marie received a book from Jan.' | ||||

The alternation in (142) is also found with particle verbs based on geven and krijgen like terug geven/krijgento give/get back and op geven/krijgen, as shown in (143).

| a. | Jan gaf | Marie het boek terug. | |

| Jan gave | Marie the book back | ||

| 'Jan returned the book to Marie.' | |||

| a'. | Marie kreeg | het boek | (van Jan) | terug. | |

| Marie got | the book | of Jan | back | ||

| 'Marie got the book back from Jan.' | |||||

| b. | De leraar | gaf | de leerlingen | te veel huiswerk | op. | |

| the teacher | gave | the pupils | too much homework | prt. | ||

| 'The teacher set his pupils too much homework.' | ||||||

| b'. | De leerlingen | kregen | te veel huiswerk | op. | |

| the pupils | got | too much homework | prt. | ||

| 'The pupils were given too much homework.' | |||||

The semantic support for the analysis of krijgen as an undative verb seems relatively weak. For example, an appeal to the meaning of the examples in (144) might also lead to the conclusion that ontvangento receive is an undative verb, since the subject of the verb ontvangento receive seems to be the counterpart of the indirect object of versturento send. However, we will see in Subsection A that there is morphosyntactic evidence for the conclusion that the subject of ontvangen is actually an agent, which means that we are dealing with a transitive verb.

| a. | Jan stuurde | Marie een boek. | |

| Jan sent | Marie a book |

| b. | Marie ontving | een boek | (van Jan). | |

| Marie received | a book | of Jan | ||

| 'Marie received a book from Jan.' | ||||

Subsection A will also show that krijgen is systematically different from ontvangen in this respect; therefore, the analysis of krijgen as an undative verb is still viable and will be further supported by the discussions in Subsection B. Finally, Subsection C will argue for the undative status of krijgen on the basis of its use as an auxiliary in so-called krijgen-passive constructions.

If the subject in (142b) is truly an internal recipient argument, we predict that er-nominalization of the presumed undative verb krijgen is excluded, since this process requires an external argument; cf. the generalization in (60a) in Section 2.1.2, sub IIG. Example (145a) shows that this prediction is correct. The verb krijgen differs in this respect from the verb ontvangento receive, which, although semantically close, has a subject that is more agent-like, in the sense that it is more actively involved in the event.

| a. | * | de krijger | van dit boek |

| the get-er | of this book |

| b. | de ontvanger | van dit boek | |

| the receiver | of this book |

We can therefore expect that the main verbs in (145) will also behave differently in imperatives, and the examples in (146) show that this expectation is borne out: only the more agent-like verb ontvangen can occur as an imperative.

| a. | We | krijgen/ontvangen | morgen | gasten. | |

| we | get/receive | tomorrow | guests | ||

| 'We will get/receive guests tomorrow.' | |||||

| b. | Ontvang/*krijg | ze | (gastvrij)! | |

| receive/get | them | hospitably | ||

| 'Receive them hospitably.' | ||||

According to generalization (60d) in Section 2.1.2, sub IIG, the presence of an external argument is a necessary condition for passivization; this would correctly predict that passivization of (142b) with the presumed undative verb krijgen is excluded. The examples in (147) show that krijgen is again different from the verb ontvangen, which allows passivization; this verb must therefore be analyzed a regular transitive verb.

| a. | * | Het boek | werd | (door Marie) | gekregen. |

| the book | was | by Marie | gotten |

| b. | Het boek | werd | (door Marie) | ontvangen. | |

| the book | was | by Marie | received |

Note that Haeseryn et al. (1997: §2.2.3, sub 3) claims that ontvangen does not allow passivization; this is clearly incorrect, as can be seen from the fact that a Google search (February 27, 2024) for the string [werd te laat gekregen/ontvangen] was received too late resulted in 46 hits for ontvangen, but none for gekregen. The claim that ontvangen must be classified as a regular transitive verb therefore stands. However, the examples in (145) and (147) are not conclusive for classifying krijgen as an undative verb, since we know that not all verbs with an external argument allow er-nominalization and that there are several additional restrictions on passivization; cf. Section 3.2.1. However, there is additional support for the hypothesis that the subject of krijgen is a derived recipient-subject.

The hypothesis that the subject of krijgen is a derived recipient-subject can explain the fact that the more or less idiomatic double object construction iemand de koude rillingen bezorgento give someone the creeps in (148a) has a counterpart in (148b) with krijgen. This would be entirely coincidental if Jan were an external argument of the verb krijgen, but it follows immediately if it originates in the same position as the indirect object in (148a); it also explains why the transitive verb ontvangen cannot be used in this context.

| a. | De heks | bezorgde | Jan de koude rillingen. | |

| the witch | gave | Jan the cold shivers | ||

| 'The witch gave Jan the creeps.' | ||||

| b. | Jan kreeg/*ontving | de koude rillingen | (van de heks). | |

| Jan got/received | the cold shivers | from the witch |

Another argument for the assumption that krijgen has an recipient-subject is that krijgen can be used in inalienable possession constructions with a locative PP such as op de vingers. The nominal part of the PP of such constructions, which typically refers to a body part, functions as a possessee and its possessor is usually expressed by a dative noun phrase. This means that (149a) expresses the same meaning as (149b), in which the possessive relation is made explicit by the possessive pronoun haarher (which makes the dative possessor optional). Cf. Section 3.3.1.4 for further discussion.

| a. | Jan | gaf | Marie | een tik | op de vingers. | |

| Jan | gave | Marie | a slap | on the fingers | ||

| 'Jan gave Marie a slap on her fingers.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan | gaf | (Marie) | een tik | op haar vingers. | |

| Jan | gave | Marie | a slap | on her fingers | ||

| 'Jan gave Marie a slap on her fingers.' | ||||||

Subjects of active constructions do not normally function as inalienable possessors of the nominal part of such locative PPs: an example such as (150a) cannot express an inalienable possession relation between the (underlying) subject Jan and the nominal part of the PP, which makes it pragmatically odd (at least when the context provides no information about the possessor of the body part). To express inalienable possession between the subject and the body part, the simplex reflexive object pronoun zich must be added, as in (150b).

| a. | ?? | Jan | sloeg | op de borst. |

| Jan | hit | on the chest |

| b. | Jan | sloeg | zich | op de borst. | |

| Jan | hit | refl | on the chest | ||

| 'Jan slapped his chest.' | |||||

Note that the reflexive pronoun in (150b) is most likely dative (rather than accusative). Of course, this cannot be seen by examining the form of the invariant weak reflexive in (150b), but it can be made plausible by examining the structurally parallel German examples in (151), in which the possessor appears as a dative pronoun; cf. Broekhuis et al. (1996) for a detailed discussion.

| a. | Ich | boxe | ihmdat | in den Magen. | |

| I | hit | him | in the stomach | ||

| 'I hit him in the stomach.' | |||||

| b. | Ich | klopfe | ihmdat | auf die Schulter. | |

| I | pat | him | on the shoulder | ||

| 'I pat his shoulder.' | |||||

The crucial observation for our present discussion is that the subject of the verb krijgen is an exception to the general rule that subjects of active constructions do not function as inalienable possessors of a body part embedded in a locative PP: it can be understood from the fact that the subject Marie is interpreted as the inalienable possessor of the noun phrase de vingers in example (152a). This follows immediately if (i) inalienable possessors must be internal recipient arguments, and (ii) the subject Marie (152a) is not an external argument but a derived recipient-subject. Example (152b) is added to show that, as in (149), the inalienable possession relation can be made explicit by the possessive pronoun haarher.

| a. | Marie | kreeg | een tik | op de vingers. | |

| Marie | got a | slap | on the fingers |

| b. | Marie | kreeg | een tik | op haar vingers. | |

| Marie | got | a slap | on her fingers |

Note that the inalienable possessive constructions in (149) and (152) all allow an idiomatic reading comparable to English to give someone/to get a rap on the knuckles, i.e. “to reprimand/be reprimanded”. This would be entirely coincidental if Marie were an external argument of the verb krijgen, but it follows immediately if it originates in the same position as the indirect object in (149); cf. the discussion of example (148).

For the sake of completeness, we performed a Google search (February 24, 2024) on the string [kreeg/ontving een tik op de vingers], which showed that the verb krijgen is once more different from the transitive verb ontvangen: the search returned 146 unique hits with kreeg, but none with ontving.

The hypothesis that krijgen is an undative verb is particularly interesting in view of the fact that it is also used as an auxiliary in the so-called krijgen-passive, in which not the direct but the indirect object is promoted to subject. This can be seen in the following examples: (153b) is the regular passive counterpart of (153a), in which the direct object is promoted to subject; example (153c) is the krijgen-passive counterpart of (153a), which involves the promotion of the indirect object to subject.

| a. | Jan bood | Marie het boek | aan. | |

| Jan offered | Marie the book | prt. |

| b. | Het boek | werd Marie | aangeboden. | |

| the book | was Marie | prt.-offered | ||

| 'The book was offered to Marie.' | ||||

| c. | Marie kreeg | het boek | aangeboden | |

| Marie got | the book | prt.-offered | ||

| 'Marie was offered the book.' | ||||

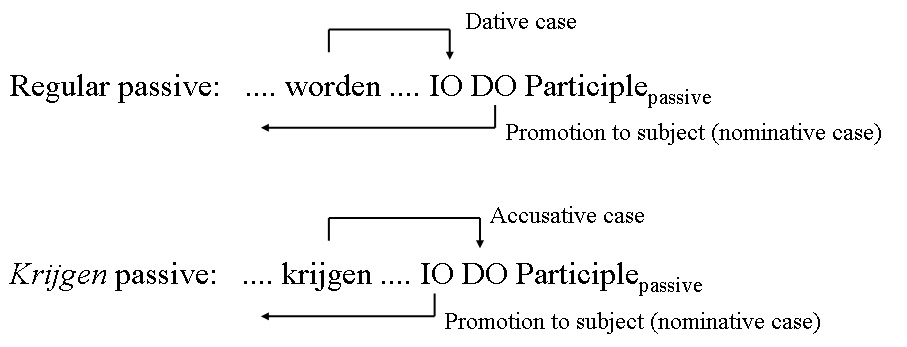

The obvious question raised by the passive constructions in (153b&c) is what determines which of the two internal arguments is promoted to subject. Since worden is clearly an unaccusative verb (e.g. it takes the auxiliary zijn in the perfect), the hypothesis that krijgen is an undative verb suggests that it is the auxiliary verb that is responsible: if the auxiliary is unaccusative, the direct object of the corresponding active sentence cannot be assigned accusative case and must therefore be promoted to subject; on the other hand, if the auxiliary is undative, the indirect object cannot be assigned dative case and must therefore be promoted to subject. Assuming that passive participles cannot assign case (cf. Section 3.2.1), the case assignment in the two types of passive construction is as shown in (154)

|

The discussion in the previous subsection has argued that the main verb krijgento get is a representative of a verb type that can be characterized as undative. This subsection will show that the verbs hebbento have and houdento keep display a very similar syntactic behavior to krijgen and therefore probably belong to the same verb class. Before doing so, however, we will discuss an important difference between krijgen on the one hand and hebben and houden on the other.

The contrast between (155a) and (155b-c) shows that krijgen, but not hebben and houden, can take a van-PP that seems to express an agent. The percentage sign in (155b) is added to express that some speakers accept this example with the van-PP, although this shifts the meaning of hebben towards that of krijgen; a more or less idiomatic example of this type is Marie heeft dat trekje van haar vaderMarie has/got that feature from her father.

| a. | Marie kreeg | het boek | (van JanAgent). | |

| Marie got | the book | from Jan |

| b. | Marie heeft | het boek | (%van JanAgent). | |

| Marie has | the book | from Jan |

| c. | Marie houdt | het boek | (*van JanAgent). | |

| Marie keeps | the book | from Jan |

The contrasts in (155) can be related to the meanings expressed by the three verbs: the construction with krijgen in (155a) expresses that the theme het boek has changed position, with the referent of the complement of the van-PP referring to its original and the subject of the clause referring to its new location. This suggests that the van-PPs express a source rather than an agent (as previously suggested). If this is the case, the fact that the van-PP in sentence (155b) is not possible with hebben is due to the fact that this verb does not denote transfer, but expresses possession. Something similar applies to sentence (155c) with houdento keep in (155c), which explicitly expresses that the transfer of the theme is not in order.

This subsection discusses data suggesting that hebben is an undative verb, on a par with krijgen. The first thing to note is that hebben does not allow er-nominalization, which distinguishes it from the verb bezittento possess, which is semantically very close to it. The contrast between (156a) and (156b) may again be related to the fact that the subject of the latter is more agent-like. This is supported by the fact that the verb hebben can be used with individual-level predicates such as grijs haar hebbento have gray hair or with non-control predicates such as de griep hebbento have the flu, whereas the verb bezitten cannot: Jan heeft/*bezit grijs haarJan has gray hair; Jan heeft/*bezit de griepJan has the flu.

| a. | * | een | hebber | van boeken |

| a | have-er | of books |

| b. | een | bezitter | van boeken | |

| an | owner | of books | ||

| 'an owner of books' | ||||

For completeness’ sake, note that there is a noun hebberd which is used to refer to a greedy person. This noun is probably lexicalized, as is clear not only from the specialization in meaning, but also from the fact that it is derived with the unproductive nominal suffix –erd, and that it does not inherit the theme argument of the input verb: een hebberd (*van boeken).

Second, hebben is like krijgen in that it cannot be passivized. Note that this is also true for the verb bezitten, which was shown to be a regular transitive verb in (156b). This again shows that passivization is not a necessary condition for a verb to be transitive.

| a. | * | Het boek | werd | (door Marie) | gehad. |

| the book | was | by Marie | had |

| b. | ?? | Het boek | werd | (door Marie) | bezeten. |

| the book | was | by Marie | owned |

For the sake of completeness, note that examples such as Marie werd bezeten door een kwade geestMarie was possessed by an evil spirit are quite common, but probably irrelevant, since such cases usually have no active counterpart; cf. Een kwade geest bezat MarieAn evil spirit possessed Marie. Probably bezetenpossessed functions here as an adjectival predicate, which is supported by the fact that it can also occur with the copula-like verb raken: cf. Marie raakte bezeten door een kwade geestMarie became possessed by an evil spirit.

Third, besides the idiomatic example in (148a), repeated as (158a), we find (158b) with a similar meaning. This would be entirely coincidental if the subject were an external argument of the verb hebben, but expected if it is an recipient-subject.

| a. | De heks | bezorgt | Jan de koude rillingen. | |

| the witch | gives | Jan the cold shivers | ||

| 'The witch gives Jan the creeps.' | ||||

| b. | Jan heeft | de koude rillingen | (??van de heks). | |

| Jan has | the cold shivers | from the witch | ||

| 'Jan has got the creeps.' | ||||

Finally, like the subject of krijgen, the subject of hebben can be used as an inalienable possessor of the nominal part of a locative PP. This would again follow if (i) inalienable possessors must be recipient arguments and (ii) the subject Peter in (159b) is not an external argument but an recipient-subject.

| a. | Jan stopt | Peter | een euro | in de hand. | |

| Jan puts | Peter | a euro | in the hand | ||

| 'Jan is putting a euro in Peter's hand.' | |||||

| b. | Peter heeft | een euro | in de hand. | |

| Peter has | a euro | in the hand | ||

| 'Peter has a euro in his hand.' | ||||

The verb houdento keep in (160a) seems to belong to the same semantic field as hebbento have and krijgento get, but expresses that there is no transfer of the theme argument. The claim that houden is an undative verb is supported by the examples in (160b-d), which show that er-nominalization and passivization are excluded, and that the subject of this verb can act as an inalienable possessor.

| a. | Marie houdt de boeken. | |

| Marie keeps the books |

| b. | * | een houder | van boeken | er-nominalization |

| a keeper | of books |

| c. | * | De boeken | worden | gehouden. | passivization |

| the books | are | kept |

| d. | Mao | hield | een rood boekje | in de hand. | inalienable possession | |

| Mao | kept | a red bookdiminutive | in the hand | |||

| 'Mao held a little red book in his hand.' | ||||||

However, several possible problems with the assumption that houden is an undative verb raise their head. First, there are cases of er-nominalization such as (161b). However, these cases are special, because the corresponding verbal construction does not occur with the intended meaning, and we can therefore conclude that we are dealing with an idiomatic noun (constructed for marketing purposes) .

| a. | * | Jan houdt | een OV-jaarkaart. |

| Jan holds | an annual.transport.card | ||

| Intended meaning: 'Jan has an annual public transport pass.' | |||

| b. | houders | van | een | OV-jaarkaart | |

| keepers | of | a | annual.transport.card | ||

| 'holders of an annual public transport pass' | |||||

Second, the (a)-examples in (162) show that there are constructions with houden that do allow passivization; the deviant behavior of these examples may be due to the fact that we are dealing with an idiomatic expression with more or less the same meaning as the transitive verb bespiedento spy on, which also allows passivization. Somewhat surprisingly, the corresponding construction with krijgen behaves as expected in that it does not allow passivization; this is illustrated in the (b)-examples.

| a. | De politie | hield | de man | in de gaten. | gaten probably refers to eyes | |

| the police | kept | the man | in the gaten | |||

| 'The police were keeping an eye on the man.' | ||||||

| a'. | De man | werd | door de politie | in de gaten | gehouden. | |

| the man | was | by the police | in the gaten | kept | ||

| 'The man was being watched by the police.' | ||||||

| b. | De politie | kreeg | de man | in de gaten. | |

| the police | got | the man | in the gaten | ||

| 'The police noticed the man.' | |||||

| b'. | * | De man werd | door de politie | in de gaten | gekregen. |

| the man was | by the police | in the gaten | got |

Third, er-nominalization and passivization are possible with the verb houden if this verb is used in reference to livestock, as in (163). However, the fact that the object in (163a) can be a bare plural (or a bare mass noun) suggests that we are dealing with a semantic (i.e. syntactically separable) compound verb, comparable to a particle verb (although it should be noted that the bare noun can be replaced by a quantified indefinite noun phrase such as veel schapenmany sheep).

| a. | Jan houdt schapen/*een schaap. | |

| Jan keeps sheep/a sheep | ||

| 'Jan is keeping sheep' |

| b. | schapenhouder ‘sheep farmer’ |

| c. | Er | worden | schapen | gehouden. | |

| there | are | sheep | kept |

We will leave the special cases in (161) to (163) for future research and rely on the more general findings in (160), which suggest that houden is an undative verb.

The class of undative verbs has not been studied extensively, so it is difficult to say anything with certainty about the size of this class; since the number of ditransitive verbs is relatively small, the same might be expected for undative verbs, which also take two internal arguments. Although this is more of a topic for future research, we will look at some other possible cases that might be included in this verb class.

Verbs of cognition like wetento know and kennento know in (164a), in which the subject of the clause does not act as an agent but as an experiencer, may belong to the class of undative verbs, in view of the fact that the thematic role of experiencer is usually assigned to internal arguments; cf. the discussion of the nom-dat verbs in Section 2.1.3. Another argument is that such verbs usually do not allow passivization, as shown in (164b); however, such passives do occur in more or less formal contexts, in which case the subject is most likely a human being: Jezus kan uitsluitend echt gekend worden door iemand die de juiste geesteshouding heeftJesus can only be known by someone who has the right spiritual attitude; they also occur in collocations like gekend worden alsto be known as and gekend worden into be consulted in.

| a. | Jan weet/kent | het antwoord. | |

| Jan knows | the answer | ||

| 'Jan knows the answer.' | |||

| b. | * | Het antwoord | wordt | (door Jan) | geweten/gekend. |

| the answer | is | by Jan | known |

Er-nominalization also suggests that cognitive verbs are undative. Although the noun kenner in (165a) exists, it does not have the characteristic property of productively formed er-nouns of inheriting the internal argument of the input verb. Moreover, kenner has the highly specialized meaning of “expert” or “connoisseur”. The noun weter in (165b) does not exist at all, although it occurs as the second member in the compounds allesweterknow-it-all and betweterpedant.

| a. | de | kenner | (*van het antwoord) | |

| the | know-er | of the answer | ||

| 'the expert' | ||||

| b. | * | de | weter | (van het antwoord) |

| the | know-er | of the answer |

The fact that these verbs do not normally occur in the imperative also suggests that the input verbs do not have an agentive argument and therefore point in the same direction; cf. Section 1.2.3, sub IIIB, for a discussion of counterexamples such as Ken uw rechten!Know your rights!.

| a. | * | Ken | het antwoord! |

| know | the answer |

| b. | * | Weet | het antwoord! |

| know | the answer |

Finally, the examples in (167) show that the subjects of these verbs can enter into an inalienable possession relation with the nominal part of a locative PP: if inalienable possessors must be recipient arguments, the subject Jan cannot be an external argument but must be a derived recipient-subject.

| a. | Jan kent | het gedicht | uit het/zijn hoofd. | |

| Jan knows | the poem | from the/his head | ||

| 'Jan knows the poem by heart.' | ||||

| b. | Jan weet | het | uit het/zijn hoofd. | |

| Jan knows | it | from the/his head | ||

| 'Jan knows this by heart.' | ||||

Other possible examples of undative verbs are behelzento contain/include, bevattento contain, inhoudento imply, and omvattento comprise. These verbs may belong to the same semantic field as hebbento have; Haeseryn et al. (1997:54) notes that these verbs are similar to hebben in rejecting passivization. However, it is not clear whether the impossibility of passivization is very informative in these cases, since many of these verbs take inanimate subjects, which may also be why they resist the formation of person nouns by er-nominalization. We therefore leave this question for future research.