- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Dutch is an official language in the Netherlands, Belgium-Flanders, Surinam, Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles. With at least 22 million native speakers (Wikipedia.org 2024), it is one of the world's major languages. It is taught and studied in more than 135 universities in 40 countries (taalunie.org/dossiers/68: January 9, 2021). Dutch is also one of the best-researched living languages; research on it has had a major and continuing impact on the development of formal linguistic theory, and it plays an important role in various other types of linguistic research. However, much information remains hidden in scientific publications: some is embedded in theoretical discussions of interest or accessible only to certain groups of formal linguists, some is more or less outdated in the light of more recent findings and theoretical developments, some is buried in publications with limited distribution, and some is simply inaccessible to large groups of readers because it is written in Dutch. This calls for a comprehensive, scientifically based description of the grammar of Dutch that is accessible to a wider international audience: the Syntax of Dutch (SoD) aims to fill this gap in the field of syntax. The Language Portal (https:\\taalportaal.org), of which the SoD is a part, provides an even more comprehensive description of the grammar of Dutch by including similar descriptions of its phonology and morphology; cf. Van der Wouden et al. (2016).

The main objective of SoD is to present a synthesis of the currently available syntactic knowledge of Dutch. It provides a comprehensive overview of relevant research on Dutch, presenting not only the results of earlier approaches to the language, but also the results of formal linguistic research over the last seven decades, since the advent of generative grammar, which are often not found in other reference works. It should be emphasized, however, that SoD is primarily concerned with language description and not with linguistic theory; the reader will generally look in vain for critical evaluations of theoretical proposals made to explain particular problems. Although SoD addresses many of the central issues in current syntactic theory, it does not provide an introduction to it. Readers interested in such an introduction are referred to one of the many existing introductory textbooks, or to handbooks like The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Syntax, edited by Martin Everaert & Henk van Riemsdijk, or The Cambridge Handbook of Generative Syntax, edited by Marcel den Dikken. A commendable publication that aims to provide a description of Dutch in a more theoretical setting is The Syntax of Dutch by Jan-Wouter Zwart in the Cambridge Syntax Guides series.

SoD is not aimed at a specific group of linguists, but at a more general readership. The intention is to produce a reference work that will be accessible to a wide audience with some training in linguistics and/or related disciplines, and that will assist all researchers interested in questions of Dutch syntax. Although we did not originally target this audience, the descriptions we provide have been proven to be accessible to advanced students of language and linguistics. Specifying our audience in this way means that we have tried to avoid the jargon of specific theoretical frameworks by using, as much as possible, the lingua franca commonly used by linguists. When we use a term that we believe is not part of the lingua franca, we provide a brief clarification of that term in the glossary. When we occasionally discuss theoretical matters, we try to do so in places where it does not interrupt the discussion of the data, although such digressions may include new data if necessary to make our point.

The object of description is aptly described by the title of this work, Syntax of Dutch. This title suggests a number of ways in which the empirical domain is limited; this will be elaborated here by briefly discussing the two terms syntax and Dutch.

Syntax is the branch of linguistics that studies how words are combined into larger phrases and, ultimately, sentences. This means that we do not systematically discuss the internal structure of words (which is the domain of morphology) or the way sentences are used in discourse (which is the domain of discourse studies and pragmatics): we digress into such matters only if it is useful for describing the syntactic properties of the language. For example, Chapter N14 contains an extensive discussion of deverbal nominalization, but only because this morphological process is relevant to the discussion of the complementation of nouns in Chapter N15. And Section N21.1.3 shows that the difference in word order between the two examples in (1) is related to the preceding discourse: when the sentence is pronounced in a neutral way (i.e. without a contrastive accent), the object Marie can only precede clausal adverbs such as waarschijnlijkprobably if it refers to a person already mentioned in (or implied by) the preceding discourse.

| a. | Jan | heeft | waarschijnlijk | Marie | gezien. | Marie = discourse new | |

| Jan | has | probably | Marie | seen | |||

| 'Jan has probably seen Marie.' | |||||||

| b. | Jan heeft | Marie | waarschijnlijk | gezien. | Marie = discourse old | |

| Jan has | Marie | probably | seen | |||

| 'Jan has probably seen Marie.' | ||||||

Our goal of describing the internal structure of phrases and sentences implies that we focus on competence (the internalized grammar of native speakers) rather than performance (the actual use of language). SoD will pay considerable attention to certain aspects of meaning and will also discuss phonological aspects such as stress and intonation where these are relevant (e.g. in the context of word order phenomena such as those in (1)). The reason for this is that current formal grammar assumes that the output of the syntactic module of the grammar consists of objects (sentences) that relate form and meaning. Furthermore, formal syntax has been quite successful in establishing and describing a large number of constraints on this relationship. A prime example of this is the formulation of the so-called binding theory, which (among other things) accounts for the fact that referential pronouns such as hemhim and anaphoric pronouns such as zichzelfhimself differ in the domain within which they can (or must) find an antecedent. For instance, the examples in (2), where the intended antecedents of the pronouns are italicized, show that referential object pronouns such as hemhim cannot have an antecedent within their minimal clause, whereas anaphoric pronouns such as zichzelfhimself must have an antecedent within their minimal clause; cf. Section N22 for a detailed discussion.

| a. | Jan denkt [Clause | dat | Peter hem/*zichzelf | bewondert]. | |

| Jan thinks | that | Peter him/himself | admires | ||

| 'Jan thinks that Peter admires him [= Jan].' | |||||

| b. | Jan denkt [Clause | dat | Peter | zichzelf/*hem | bewondert]. | |

| Jan thinks | that | Peter | himself/him | admires | ||

| 'Jan thinks that Peter admires himself [= Peter].' | ||||||

SoD provides a syntactic description of what we will loosely refer to as Standard Dutch, although we are aware that there are many problems with this term; cf. Milroy (2001). First, the term Standard Dutch is often used to refer to the written language and the more formal registers, which are widely perceived as more prestigious than the colloquial uses of the language. Second, the term suggests that there is an invariant language system shared by a large group of speakers. Third, the term bears the connotation that some, often unnamed, authority is able to determine what should or should not be considered part of the language, or what should or should not be considered proper language use.

SoD does not provide a description of this prestigious, invariant, externally determined language system. The reason for this is that knowledge of this system is not related to the competence (i.e. internalized grammar) of individual language users, but “is the product of a series of educational and social factors which have overtly impinged on the linguistic experiences of individuals, prescribing the correctness/incorrectness of certain constructions” (Adger & Trousdale 2007). Instead, the notion of standard language in SoD should be understood more neutrally as an idealization referring to certain properties of linguistic competence that can be assumed to be shared by individual speakers of the language. Our notion of standard Dutch, which will henceforth be written with a single capital letter, differs from the traditional notion of Standard Dutch, written with two capitals, in that it may include properties that would be rejected by language teachers, and it may exclude certain properties that are explicitly taught as part of the standard language. To put the latter in more technical terms, our notion of standard Dutch refers to the core grammar of Dutch (i.e. those aspects of the language system that arise spontaneously in the language-learning child through exposure to utterances in the standard language) and excludes the periphery (those properties of the standard language that are explicitly taught at a later age). This does not mean that we ignore the more peripheral aspects completely, but it should be kept in mind that they have a special status and may have properties alien to the core system.

A distinguishing feature of standard Dutch is that it can be used by speakers of different dialects; speakers of such dialects sometimes have to acquire it as a second language at a later age, i.e. in a way similar to a foreign language (although this may be rare in the context of Dutch). This implies that there is no contradiction in distinguishing different varieties of standard Dutch. A largely similar view is taken in Haeseryn et al. (1997: Section 0.6.2), where the fourfold distinction in (3) is made when it comes to geographically determined variation.

| a. | Standard Dutch |

| b. | regional variety of standard Dutch |

| c. | regional variety of Dutch |

| d. | dialect of Dutch |

The types in (3b&c) are characterized by certain properties that are found only in certain larger but geographically limited regions. The distinction between the two types of regional varieties is defined by Haeseryn at al. (1997) by appealing to the perception of the properties in question by other speakers of the standard language: if the majority of these speakers do not consider the property in question to be characteristic of a particular geographical region, the property belongs to a regional variety of standard Dutch; if the property in question is unknown to some speakers of the standard language or is considered to be characteristic of a particular geographical region, it belongs to a regional variety of Dutch. We will not adopt the distinction between the types in (3b) and (3c), since we are not aware of any large-scale perception studies that could help us distinguish between the two varieties in question. We will therefore simply merge the two categories into one, as in (4).

| a. | standard Dutch |

| b. | regional variety of standard Dutch |

| c. | dialect of Dutch |

We think it is helpful to think of the types of language variety in (4) in terms of grammatical properties that are common to the competence of groups of speakers. This means that we can see standard Dutch as a set of properties that are part of the competence of all speakers of the language. Examples of such properties in the nominal domain are that non-pronominal noun phrases are not morphologically case-marked and that the word order within noun phrases is such that nouns normally follow attributively used adjectives but precede PP-modifiers and that articles precede attributive adjectives (if present); cf. (5a). Relevant properties within the clausal domain are that finite verbs occupy the co-called second position in main clauses, while non-finite verbs cluster on the right side of the clause, as in (5b), and that finite verbs join the clause-final non-finite verbs in embedded clauses, as in (5c).

| a. | de | oude | man | in de stoel | word order within noun phrases | |

| the | old | man | in the chair |

| b. | Jan | heeft | de man | een lied | horen | zingen. | verb second/clustering | |

| Jan | has | the man | a song | hear | sing | |||

| 'Jan has heard the man sing a song.' | ||||||||

| c. | dat | Jan | de man | een lied | heeft | horen | zingen. | verb clustering | |

| that | Jan | the man | a song | has | hear | sing | |||

| 'that Jan has heard the man sing a song.' | |||||||||

Regional varieties of Dutch are then defined as having a set of additional properties that are part of the competence of larger subgroups of speakers. Such properties define certain special characteristics of the variety in question, but do not normally give rise to linguistic outputs that are inaccessible to speakers of other varieties; see the discussion of (6) below for a typical example. Dialects can be thought of as having a set of additional properties that are part of the competence of a smaller group of speakers in a restricted geographical area. Such properties may be alien to speakers of standard Dutch and may give rise to linguistic outputs that are not immediately accessible to other speakers of Dutch; see example (8) below for a possible case. This way of thinking about the typology in (4) allows us to use language types in a more gradual way, which may do more justice to the situation we actually find. It also makes it possible to define varieties of Dutch along different (e.g. geographical and social) dimensions.

The examples in (6) provide an example of a property that belongs to regional varieties of Dutch: speakers of northern varieties of Dutch require that the indefinite direct object boekenbooks precede all verbs in clause-final position, while many speakers of southern varieties of Dutch (especially those spoken in the Flemish part of Belgium) will also allow the object to permeate the verb sequence, provided that it precedes the main verb.

| a. | dat | Jan <boeken> | wil <*boeken> | kopen. | Northern Dutch | |

| that | Jan books | wants | buy | |||

| 'that Jan wants to buy books.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan <boeken> | wil <boeken> | kopen. | Southern Dutch | |

| that | Jan books | wants | buy | |||

| 'that Jan wants to buy books.' | ||||||

Dialects of Dutch can differ from standard Dutch in many ways. For example, several dialects have morphological agreement between the subject and the complementizer, as illustrated in (7) by examples taken from Van Haeringen (1939); see Haegeman (1992), Hoekstra & Smit (1997), Zwart (1997), Barbiers et al. (2005) and the references cited there for more examples and detailed discussion. Complementizer agreement is a typical dialect feature: it does not occur in (the regional varieties of) standard Dutch.

| a. | Assg | Wim | kompsg, | mot | jə | zorgə | dat | je | tuis | ben. | |

| when | Wim | comes | must | you | make.sure | that | you | at.home | are | ||

| 'When Wim comes, you must make sure to be home.' | |||||||||||

| b. | Azzəpl | Kees en Wim | komməpl, mot | jə | zorgə | dat | je | tuis | ben. | |

| when | Kees and Wim | come | must | you make.sure | that | you | home | are | ||

| 'When Kees and Wim come, you must make sure to be home.' | ||||||||||

The examples in (8) illustrate another feature that belongs to a certain set of dialects. Speakers of most varieties of Dutch would agree that the use of possessive datives is possible only in a limited set of constructions: whereas possessive datives are possible in constructions such as (8a), in which the possessee is embedded in a °complementive PP, they are excluded in constructions such as (8b), in which the possessee is a direct object. Constructions such as (8b), if understood at all, are perceived as belonging to certain eastern and southern dialects, which is indicated here by a percentage sign.

| a. | Marie zet | Peter/hempossessor | het kind | op de kniepossessee. | |

| Marie puts | Peter/him | the child | onto the knee | ||

| 'Marie puts the child on Peterʼs/his knee.' | |||||

| b. | % | Marie wast | Peter/hempossessor | de handenpossessee. |

| Marie washes | Peter/him | the hands | ||

| 'Marie is washing Peterʼs/his hands.' | ||||

Note that the typology in (4) should allow for certain dialectal features to become part of certain regional varieties of Dutch, as indeed seems to be the case for possessive datives of the type in (8b); cf. Cornips (1994). This again shows that it is not possible to draw sharp dividing lines between regional varieties and dialects, which emphasizes that we are dealing with dynamic systems; cf. the discussion of (4) above. For our limited purpose, however, the proposed distinctions seem sufficient.

The reader should bear in mind that the description of the types of Dutch in (4) in terms of properties of the competence of groups of speakers implies that standard Dutch does not refer to a language in the traditional sense; it refers only to a subset of properties common to all non-dialectal varieties of Dutch. The selection of one of these varieties as Standard Dutch in the more traditional sense is a political rather than a linguistic enterprise and therefore need not concern us here. For practical reasons, however, we will focus on the (prestigious) regional variety of Dutch spoken in the northwestern part of the Netherlands. One reason is that the authors who have contributed to SoD are all native speakers of this variety; this focus allows them to simply appeal to their own intuitions to determine whether or not this variety exhibits a particular property. A second reason is that this variety seems to be close to the varieties that have been discussed in the linguistic literature on Standard Dutch (in the traditional sense). This does not mean that we will not discuss other varieties of Dutch, but we will only do so if we have reason to believe that they behave differently. Unfortunately, however, not much is known about the syntactic differences between the various varieties of Dutch. Since this not part of our present goal to solve this problem, we would like to ask the reader to limit the judgments made in SoD to speakers of the Northwestern variety, unless noted otherwise. In the vast majority of cases, the other varieties of Dutch will show identical or similar behavior, since the behavior in question reflects properties that are part of standard Dutch (in the technical sense). However, this cannot be taken for granted, as it cannot be ruled out with certainty at this stage that they may occasionally reflect properties of the regional variety spoken by the author(s).

Section IV has stated that the main goal of SoD is to provide an up-to-date syntactic description of standard Dutch, i.e. a description of the way in which words are combined into larger phrases and sentences in core syntax. This means that we aim to describe (in a more or less informal way) the competence of native speakers rather than their performance. In order to do this, we will make extensive use of acceptability judgments on constructed examples ready made for the syntactic problems at hand. For practical reasons, these judgments will be based on the existing literature, the intuition of the researcher, or linguistically trained informant(s).

Not so long ago, it seemed unnecessary to motivate the use of acceptability judgments, now sometimes referred to as the intuitionist approach to the study of syntax. The first edition of SoD was criticized for using this method of data collection, however. The various reviews which appeared in Nederlandse Taalkunde/Dutch Linguistics (issues 19/1-2 and 21/2) left no doubt that some reviewers consider the intuitionist approach inadequate: a reference grammar such as Syntax of Dutch should preferably be based on corpus data. The assumption underlying this claim seems to be that introspection data are not (reliable) empirical data and are therefore inherently inferior to corpus data based on actual performance, or “real language” in the words of De Hoop (2016). The rejoinder to these reviews in Broekhuis (2016) aimed at showing that these reviewers were too optimistic about the potential of corpus linguistics: at least some of their suggested improvements and corrections of the proposed descriptions in SoD turned out to be problematic themselves on two counts: they were either based on “raw” corpus data or there were shortcomings in the linguistic annotation of the corpora used.

The rejection of the intuitionist approach is not universal and is probably related to the fact that the research interests of some reviewers are better served by corpus research. This can be seen from the fact that other reviewers explicitly praised the use of the intuitionist approach in SoD (cf. Smessaert 2014), and some corpus linguists consider acceptability judgments to be of similar value as corpus data; cf. the discussion between Schoenmakers & Van Hout (2024) and Weerman (2024). For example, Odijk (2020: 12) emphasizes that data from corpora and data collected in artificial experimental settings (including introspection) should all be considered empirical data: “all relevant evidence should be considered, and no form or source of evidence has a privileged status” (our translation). Although we agree with Odijk’s statement in principle, there are reasons to think that the intuitionist approach is in fact better suited for collecting synchronic syntactic data than corpus research (evidently not for linguistic research in e.g. diachronic syntax, language variation, and language acquisition; here, corpus research is indispensable). This seems to justify a more general comparison of the two methods of data collection. The following discussion is largely based on earlier discussions by Newmeyer (1983) and Kübler and Zinsmeister (2015), and has previously been published in a slightly different form as Broekhuis (2020).

The suitability of the two methods of data collection under discussion (i.e. the use of acceptability judgments on constructed examples or the mining of corpora) for SoD is closely related to the type of data needed to study synchronic syntax. Studying the internal organization of phrases/sentences is not an easy task, and progress has been slow but steady since the introduction of generative grammar in the mid-1950s. The complexity of syntactic structures is not immediately apparent from actual utterances but must be brought to light in an indirect way by applying a series of sophisticated and sometimes controversial syntactic tests. This is used in generative grammar as evidence for postulating a certain amount of tacit knowledge in the mind/brain of the language user, needed for the production and processing of such structures. Although relatively little is known about the form of syntactic knowledge in the mind/brain, a great deal is known about the presumably universal principles that determine what are (un)grammatical, i.e. (im)possible, syntactic structures. The set of universal principles determining syntactic structure is thought to be the innate part of the adult language user’s internal language or competence that determines the properties of his language and is also thought to be instrumental in language acquisition. If this is true, then the study of the syntax of a particular language L is not only of interest in itself, but also crucial for the study of the universal mechanisms underlying the human ability to produce, process, and acquire language.

Some linguists deny the existence of competence in the generative sense: a relatively stable knowledge state that emerges in the language-learning child at a relatively early age (say, before adolescence). For example, the usage-based theory:

“[…] incorporates the basic insight that usage has an effect on linguistic structure. It thus contrasts with the generative paradigm’s focus on competence to the exclusion of performance and rather looks to evidence from usage for the understanding of the cognitive organization of the grammar” (Bybee & Beckner, 2010).

However, even if the “basic insight that usage has an effect on linguistic structure” were beyond doubt, it would not mean that the universal principles determining syntactic structure discovered by generative research should be abandoned. The reason is that these principles are claimed to hold for any adult syntactic knowledge system about a language, regardless of whether such a system should be considered a stable or a more flexible knowledge state: if such systems were flexible, the universal principles would simply hold for all successive stages.

Given the empirical and explanatory success attributed to universal principles by generative linguists, it is clearly insufficient to dismiss these principles simply by pointing to the supposedly flexible nature of the grammatical system, as is done in Van de Velde (2014:89); one would at least expect an attempt at refuting these principles on empirical grounds. While there are many generative studies attempting this as part of the normal scientific practice of theory evaluation, we are not aware of any usage-based study that specifically aims to do so.

We want to argue that the postulation of such universal principles as an innate part of the knowledge state of language users is empirically grounded. This implies that the distinction between competence and performance is also meaningful for individual speakers: competence refers to the mechanisms within the individual that are necessary for the production and processing of the abstract linguistic objects that generative grammar refers to as phrases/sentences; performance refers to everything related to the use of utterances built on these abstract objects. Since it is not important for the present discussion what the substance of competence is, the reader can simply think of it in a fairly theory-neutral way as a set of hypotheses about the internal structure of phrases (including sentences), as such relevant to all linguists interested in syntax. For this reason, we present SoD as a tool for all linguists, regardless of their theoretical background.

Competence enables the individual speaker to produce and process structured linguistic objects. Syntactic research aims at modelling the knowledge state of the adult speaker and by comparing the knowledge states of larger groups of native speakers of the same or different languages at uncovering the universal principles that enable the child to acquire natural language. Achieving these goals is a step-by-step process: based on the analysis of a necessarily limited number of syntactic phenomena in a limited number of languages, hypotheses are proposed about the universal principles to which linguistic objects are subject. These universal principles can exert an influence on the analysis of the original data set by making a selection among the competing analyses which can, in principle, explain it. They can also make predictions about other, unrelated syntactic phenomena as well as the syntactic behavior of languages not previously considered. This leads to a gradual expansion of empirical coverage, which may lead to revised or new hypotheses about the universal principles. By going through this process again and again, we hope to increase our insight into the universal properties of the competence of speakers of different languages.

The data considered in competence research can be selected rather arbitrarily: any set that the researcher considers suitable for fruitful investigation will do. However, there are two concepts that may help narrow down the data set for further research, namely acceptability and grammaticality; cf. Newmeyer (1983:§2.2). Grammaticality is the easier concept to define, since it is a theoretical term: a syntactic object is grammatical if the language user is predicted to be able to produce it, and ungrammatical if the language user is predicted not to be able to produce it. However, the term is still problematic because competence theory is constantly being updated, which implies that certain objects may be characterized as grammatical at one stage of the theory and as ungrammatical at another (and vice versa). The term acceptability is not a theoretical term, but refers to the feelings/intuitions that language users have about utterances. Of course, these feelings/intuitions depend on the speaker’s competence, but they can also be affected by many other factors, like the interpretability of the utterance, the usability of the utterance in the intended context, and language norms. Moreover, acceptability has little to do with actual use, since speakers may produce utterances that they find unacceptable upon closer inspection; this is a first reason why “raw” data collected by corpus research are less suitable for syntactic research.

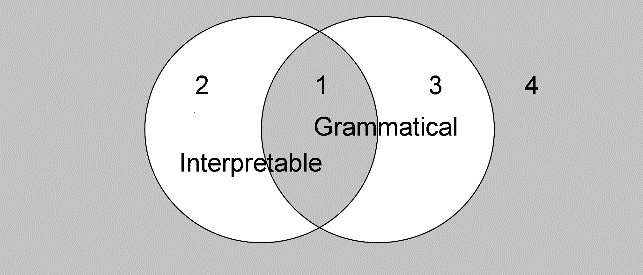

The reason why the notions of acceptability and grammaticality are helpful in restricting the data set is that there appears to be a consensus that at least those utterances frequently produced in colloquial speech and judged acceptable by native speakers should be included in the set of grammatical sentences; likewise, that utterances that occur infrequently (or never) in colloquial speech and are judged unacceptable by native speakers should be included in the set of ungrammatical sentences. We will illustrate this by considering two factors that affect the acceptability of linguistic forms, grammaticality and interpretability. Figure 1 shows that these factors divide any data set into four, possibly empty, subsets (conveniently ignoring the many other factors that may affect acceptability judgments):

Figure 1: Two important factors affecting acceptability

The nature of subset 1 (grammatical and interpretable) will be unproblematic for most readers, as these are the forms that all native speakers will characterize as acceptable, i.e. as belonging to their language; we can therefore expect these forms to occur in the speech produced by native speakers. The same will hold for subset 4 (ungrammatical and uninterpretable), as these are the forms that all native speakers will characterize as unacceptable; we can expect these forms not to occur in the speech of native speakers (although they may occur in the speech of non-native speakers). Subset 2 (interpretable but ungrammatical) is a mixed bag that may include incomplete utterances, anacoluthon, speech errors of many kinds, and so on. Subset 3 (grammatical but uninterpretable) is more problematic, since the decision to place a particular form in this subset depends on the grammar adopted. For example, whether Chomsky’s famous example Colorless green ideas sleep furiously belongs to this subset depends on whether the grammar contains selection restrictions such as “the verb sleep takes an animate subject”: if it does, the sentence belongs to subset 4; if it does not, the sentence belongs to subset 3. There are many forms for which it can be difficult to decide where they belong. For example, native speakers of Dutch occasionally place pseudo-participles (adjectives with the appearance of a participle) such as geliefdpopular after the verbs in clause-final position, as in (9b).

| a. | Marie zegt | dat | zijn boeken | geliefd | zijn. | |

| Marie says | that | his books | popular | are | ||

| 'Marie says that his books are popular.' | ||||||

| b. | ? | Marie zegt dat zijn boeken zijn geliefd. |

Some researchers may place (9b) in subset 2, while others may think that it belongs to subset 1, or that it illustrates an ongoing language change. The fact that the choice depends on the syntactic theory one supports has led to the methodological guideline that such examples should not be used to evaluate theories: the prevailing theory at the time should decide whether the example should be considered grammatical or not. Thus, the theory should preferably be based only on clear (i.e. undisputedly grammatical/ungrammatical) cases. This would avoid ad hoc additions to the theory or the elimination of otherwise well-motivated mechanisms from the theory on shaky grounds; however, we should note that there are incidental examples where the study of unclear cases has yielded important theoretical insights, such as the study of parasitic gaps). This means that competence research should use the clear cases from subset 1 and 4 for theory evaluation and exclude the cases from subset 2 and 3 for this purpose. So far, the set of clear cases (much of which remains to be explored) has provided sufficient material for new and challenging research; we think that there is reason to believe that it will continue to do so for a long time to come. We may hope that by the time the set of clear cases is exhausted, we will have enough information to be able to say something meaningful about the less clear cases. Unfortunately, corpus research is not going to help solve the problem of unclear cases either, since showing that a particular construction is attested in a corpus says little or nothing about its place in Figure 1. Therefore, the best we can do in our syntactic description is to distinguish between unquestionably grammatical and ungrammatical examples (i.e. the cases that should be accounted for by any syntactic theory) and the unclear cases (whose grammaticality should be determined by the prevailing theory of the time).

Critics of Syntax of Dutch disapprove of the use of introspection data because they are thought to be subjective and unreliable in the sense that acceptability judgments can be theoretically biased. There seems to be little ground for distrusting introspection data, as the few available studies suggest that the reliability of data sets based on introspection is not significantly lower than that of those based on corpora: where the two can be compared, convergence seems to be the rule rather than the exception; cf. Sprouse & Almeida 2010. One reason for this is that there are various checks and balances on the introspection data found in the literature, to the extent that they are not truly subjective but intersubjective: a researcher who is not entirely sure of his judgments will usually consult others for their judgments in order to sharpen his own. Moreover, data are usually peer-reviewed before publication and may be subject to post-publication scrutiny in subsequent work on the same topic. When in doubt, there is always the option of investigating the forms in question through more controlled research (such as large-scale intuition research). Faulty introspection data will usually be corrected before the research is published, or have little chance of surviving because they are simply forgotten over time as no one cites them.

It is important to keep in mind that the judgments in SoD are not about the grammaticality, but about the acceptability of the examples in question. Examples without diacritics are considered perfectly acceptable by native speakers, and one would probably (but not necessarily) want to mark them as grammatical in any theoretical account of the language, i.e. to place them in subset 1 in Figure 1. Examples preceded by an asterisk are considered unacceptable by native speakers, and one would probably (but again not necessarily) want to mark them as ungrammatical in any theoretical account of the language, i.e. to place them in subset 4 in Figure 1. The unclear cases in subsets 2 and 3 are usually preceded by a question mark, but since not all examples in these subsets are the same in that some are felt to be more deviant than others, we will occasionally make finer distinctions.

*Fully unacceptable form

*?Probably an unacceptable form

??May be an unacceptable or a disfavored form

?Disfavored form

(?)Slightly marked but probably acceptable form

no markingPerfectly acceptable form

The diacritics above thus express graded judgments within a given set of examples: examples without marking are clearly acceptable and those with an asterisk are clearly unacceptable, with various cases in between. Recall that the deviation of a given example does not necessarily mean that we should consider it ungrammatical; if there is good reason for assuming that the example is deviant for e.g. semantic or pragmatic reasons, or that it belongs not to the core but to the periphery of the grammar, the example is marked with a dollar sign $. If we are dealing with an example that is unacceptable in one reading, but acceptable in another, unintended reading, the number sign # is used. The percentage sign % is used when we know that there is speaker variation in judgments among speakers of standard Dutch. What does not seem very useful is to argue about the relative judgments of examples in different sets of examples. For example, the diacritical mark ?? does not refer to a degree of unacceptability that can be objectively assigned to examples of a certain kind: it is just a warning flag, signaling “this example is pretty bad and one should seriously consider that it might be ungrammatical”. The same goes for the diacritical mark (?), which means something like “this example is pretty good and should probably be considered grammatical”. Ultimately, it is the syntactic analysis that decides on grammaticality.

This subsection will show that compiling a data set using the intuitionist approach is usually a fairly organized process. This will be illustrated using the data set compiled in Broekhuis and Den Dikken (2018). Their investigation starts with the simple observation that the PP tot aan1 het einde aan2 toe up to the end can be reduced by omitting aan1, aan2, and/or toe. By systematically going through all possible combinations, we are able to construct the data set in (10).

| a. | tot | het einde | |

| to | the end |

| a'. | tot | aan1 | het einde | |

| to | on | the end |

| b. | tot | het einde | toe | |

| to | the end | to |

| b'. | tot | aan1 | het einde | toe | |

| to | on | the end | to |

| c. | tot | het einde | aan2 | toe | |

| to | the end | on | to |

| cʹ. | tot | aan1 | het einde | aan2 | toe | ||

| to | on | the end | on | to |

| d. | * | tot | het einde | aan2 |

| to | the end | on |

| d'. | * | tot | aan1 | het einde | aan2 |

| to | on | the end | on |

The primeless examples show that aan2 and toe are both optional, but that toe must be present if aan2 is overtly realized. The contrast between the primeless and primed examples shows that aan1 is optional in all acceptable primeless cases. Applying the standard use of parentheses to indicate optionality, we can refer collectively to all and only the acceptable forms in (10) using the string tot (aan) het einde ((aan) toe).

The fact that there are subtle meaning differences between the acceptable forms in (10) is taken as evidence for the claim that the syntactic structures of these forms are different. However, they all have the same distribution; they can all be used only as adverbial phrases of time and place, as in the primeless examples in (11). This is arguably related to the fact that the preposition tot cannot be omitted in these examples; with toe present, the omission of tot leads to unacceptability, as indicated by the asterisk in the singly primed examples; with toe absent, the result is unacceptable or leads to the loss of the intended “up to” interpretation, as indicated by the hash sign in the doubly primed examples.

| a. | Jan | heeft | tot | (aan) | het einde | ((aan) | toe) | geslapen. | time | |

| Jan | has | to | on | the end | on | to | slept | |||

| 'Jan has slept up to the end (of e.g. the meeting).' | ||||||||||

| a'. | * | Jan heeft (aan) het einde (aan) toe geslapen. |

| a''. | Jan heeft *(#aan) het einde geslapen. |

| b. | Jan | heeft | het gras | tot | (aan) | het einde | ((aan) | toe) | verwijderd. | spatial | |

| Jan | has | the grass | to | on | the end | on | to | removed | |||

| 'Jan has removed the grass up to the end (e.g. from the garden path)' | |||||||||||

| b'. | * | Jan heeft het gras (aan) het einde (aan) toe verwijderd. |

| b''. | Jan heeft het gras *(#aan) het einde verwijderd. |

Given the independently established fact that the lexical heads of phrases must be overtly realized in non-ellipsis contexts (due to the principle of recoverability), the examples in (11) can be taken as evidence for the claim that tot is the head in all PP-constructions, which takes the remainder of the PPs as its complement, as in (12).

| [PP tot [(aan) het einde ((aan) toe)]] |

Another crucial observation for the syntactic analysis is given in (13): the string aan het einde in the acceptable primed examples in (10) can be replaced by the adverbial proforms daarthere and danthen.

| a. | tot aan het einde |

| a'. | tot daar/dan |

| b. | tot aan het einde toe |

| b'. | tot daar/dan toe |

| c. | tot aan het einde aan toe |

| c'. | tot daar/dan aan toe |

Given the independently established fact that such a substitution is only possible with phrases, the examples in (13) show that aan het einde is a PP embedded in the complement of tot. On the assumption that toe is a postposition, this leads to the syntactic structures in the primeless examples in (14), where the PPs are numbered according to their depth of embedding. The structures in the primed examples follow from the plausible assumption that the NP het einde is in a similar position as the PP aan het einde.

| a. | [PP1 tot [PP2 aan het einde]] |

| a'. | [PP tot [NP het einde]] |

| b. | [PP1 tot [PP2 [PP3 aan het einde] toe]] |

| b'. | [PP1 tot [PP2 [NP het einde] toe]] |

| c. | [PP3 tot [PP2 [PP3 aan het einde] aan toe]] |

| c'. | [PP3 tot [PP2 [NP3 het einde] aan toe]] |

To arrive at a full analysis of the paradigm, we still need to explain the occurrence of aan2 in the (c)-examples and the unacceptability of the (d)-examples in (10), but we refer the reader to the article for the full analysis, as the above is sufficient for our limited purpose of showing how the intuitionist researcher assembles the data set. The main finding is that the research question in a sense dictates how the data set should be expanded to find a proper answer; it is not easy to see how corpus research could be helpful in assembling the paradigms needed to answer (let alone formulate) the relevant question.

Since the rejection of introspection data is not based on actual research, the suggestion that linguistic research should be based on corpus research simply reflects a prejudice of some researchers in favor of corpus data. An important question is whether this prejudice is justified in terms of the suitability of the data found in corpora for synchronic syntactic research. The answer is clearly negative, as can be seen from the following three quotes from the careful discussion in Kübler and Zinsmeister’s (2015:17) handbook on corpus linguistics of “three shortcomings of corpus data that users need to be aware of”.

1. The competence-performance dichotomy: “[...] corpus data are always performance data in the sense that they are potentially distorted by external factors such as incomplete sentences, repetitions, and corrections in conceptionally spoken language, or text-genre related properties in conceptionally written language such as nominalizations in law-related texts.”

The competence researcher who relies on corpus data is thus forced to weed out the unclear data in order to meet the methodological requirement that competence theory be based on clear cases (cf. Subsection VB), which can only be done by appealing to ... intuition.

2. The completeness of the data set: “[...] corpora are always limited; even web-based mega corpora comprise only a limited number of sentences. This means that there is a certain chance that the web pages with the linguistically interesting variant might just have been omitted by chance when the corpus was created.”

The situation is even more serious, as Kübler and Zinsmeister (2015:166) add that linguistically annotated corpora cannot be used to search for rare examples. The competence researcher relying on corpus data is thus forced to supplement the data set with the missing cases, which can only be done by appealing to ... intuition.

3. The third quote concerns negative evidence: “[...] corpus data will never provide negative evidence in contrast to acceptability judgements – even if there are ungrammatical examples in corpora. This means that corpus data do not allow us to test the limits of what belongs to the language and what does not.”

Given that establishing “the limits of what belongs to the language and what does not” is the core business of the competence researcher, this quote suggests that the competence researcher who relies on corpus data can only do his job if he supplements the data set with the negative evidence, which can only be done by appealing to ... intuition.

The conclusion to be drawn from the quotes from Kübler and Zinsmeister (2015:17) can only be that without an appeal to introspection data, there can be no competence research. Corpus data is inherently unsatisfactory for this kind of research: it can at best be used for adjusting intuitionist claims about clear data by showing that an allegedly unacceptable example occurs with a high frequency, or that an allegedly acceptable example does not occur at all, but even then, introspection is needed. On the other hand, it is clear that intuitionist research has had a major impact on corpus research in the guise of the tag sets used: “the most common type of linguistic annotation is part-of-speech annotation which can be applied automatically with high accuracy, and which is already very helpful for linguistic analysis despite its shallow character” (Kübler and Zinsmeister (2015:17). After all, part-of-speech annotation is based on the results of centuries of intuitionist linguistic research and thus transfers all the presumed subjectivity and unreliability of the intuitive approach to corpus research. An additional problem is that the shallow nature of the (partly outdated) annotation means that it requires a lot of creative thinking on the part of the corpus researcher to select the data relevant to specific research questions, and even then, the results are questionable when it comes to evaluating competence research; cf. Broekhuis’ (2016) remarks on the corpus study in Van Bergen and De Swart (2010). These problems can only be solved by developing more sophisticated annotation systems, which can only be provided by ... intuitionist research.

SoD is divided into four main parts that focus on the four lexical categories: verbs, nouns, adjectives, and adpositions. Lexical categories have denotations and usually take arguments: nouns denote sets of entities, verbs denote states of affairs (activities, processes, etc.) in which these entities may be involved, adjectives denote properties of entities, and adpositions denote (temporal or spatial) relations between entities.

Of course, the four lexical categories do not exhaust the set of word classes; there are also functional categories like complementizers, articles, numerals, and quantifiers. Such elements normally play a role in phrases headed by the lexical categories: articles, numerals, and quantifiers are normally part of noun phrases, and complementizers are part of clauses (i.e. verbal phrases). For this reason, these functional elements will be discussed in relation to the lexical categories.

The first four main parts of SoD are entitled Xs and X phrases, where X stands for one of the lexical categories; each part discusses one lexical category and the ways in which it combines with other elements (e.g. arguments and functional categories) to form constituents. Furthermore, these four parts of SoD all have more or less the same overall organization, in the sense that they contain (one or more) chapters on the topics discussed in the subsections below.

Each main part begins with an introductory chapter that provides a general characterization of the lexical category under discussion by describing some of its most salient properties. The reader will find here not only a brief overview of the syntactic properties of these lexical categories, but also relevant discussions of morphology (e.g. the inflection of verbs and adjectives) and semantics (e.g. the aspectual and tense properties of verbs). The introductory chapter will also discuss ways in which the lexical categories can be divided into smaller natural subclasses.

Most of the work deals with the internal structure of the projections of lexical categories/heads. These projections can be divided into two subdomains, the lexical domain and the functional domain. Taken together, the two domains are sometimes referred to as the extended projection of the lexical head in question; cf. Grimshaw (1991). We will see that there is good reason to assume that the lexical domain is embedded in the functional domain, as in (15), where LEX stands for the lexical heads V, N, A or P, and F stands for one or more functional heads like the article dethe or the complementizer datthat.

| [functional ... f ... [lexical .... lex .....]] |

The lexical domain of a lexical head is the part of its projection that affects its denotation. The denotation of a lexical head can be affected by its complements and its modifiers, as can be easily seen in the examples in (16).

| a. | Jan leest. | |

| Jan reads |

| b. | Jan leest | een krant. | |

| Jan reads | a newspaper |

| c. | Jan leest | nauwkeurig. | |

| Jan reads | carefully |

The phrase een krant lezento read a newspaper in (16b) denotes a smaller set of states of affairs than the phrase lezento read in (16a), and so does the phrase nauwkeurig lezento read carefully in (16c). The elements in the functional domain do not affect the denotation of the lexical head, but provide different kinds of additional information.

Lexical heads function as predicates, which means that they normally take arguments, i.e. they enter into so-called thematic relations with entities that they semantically imply. For example, intransitive verbs normally take an agent as their subject; transitive verbs normally take an agent and a theme, which are syntactically realized as their subject and their object, respectively; and verbs like wachtento wait normally take an agent, which is realized as their subject, and a theme, which is realized as a prepositional complement.

| a. | JanAgent | lacht. | intransitive verb | |

| Jan | laughs |

| b. | JanAgent | weet | een oplossingTheme. | transitive verb | |

| Jan | knows | a solution |

| c. | JanAgent | wacht | op de postbodeTheme. | verb with PP-complement | |

| Jan | waits | for the postman |

Although this is often less obvious with nouns, adjectives, and prepositions, it is possible to describe examples like those in (18) in the same terms. The bracketed phrases can be seen as predicates which are predicated of the noun phrase Jan, which we can therefore call their logical subject (we use small caps to distinguish this term from the term nominative subject of the clause). Furthermore, the examples in (18) show (i) that the noun vriend can be combined with a PP-complement that provides further information needed to identify the person with whom the subject Jan is in a relationship of friendship, (ii) that the adjective trotsproud can optionally take a PP-complement that identifies the subject matter of which the subject Jan is proud, and (iii) that the preposition onderunder can take a nominal complement that refers to the location of its subject Jan.

| a. | Jan is [een vriend | van Peter]. | |

| Jan is a friend | of Peter |

| b. | Jan is [trots | op zijn dochter]. | |

| Jan is proud | of his daughter |

| c. | Marie stopt | Jan [onder | de dekens]. | |

| Marie puts | Jan under | the blankets |

The fact that the italicized phrases are complements is somewhat obscured by the fact that there are certain contexts in which they can easily be omitted (e.g. when they express information that the addressee can infer from the linguistic or non-linguistic context). However, the fact that they are always semantically implied shows that they are semantically selected by the lexical head.

The projection consisting of a lexical head and its arguments can be modified in various ways. For instance, the examples in (19) show that the projection of the verb wachtento wait can be modified by different adverbial phrases: they indicate when and where the state of affairs of Jan waiting for his father took place.

| a. | Jan wachtte | gisteren | op zijn vader. | time | |

| Jan waited | yesterday | for his father | |||

| 'Jan waited for his father yesterday.' | |||||

| b. | Jan wacht | op zijn vader | bij het station. | place | |

| Jan waits | for his father | at the station | |||

| 'Jan is waiting for his father at the station.' | |||||

The examples in (20) show that the lexical projections of nouns, adjectives and prepositions can also be modified; the modifiers are italicized.

| a. | Jan is een vroegere vriend | van Peter. | |

| Jan is a former friend | of Peter |

| b. | Jan is erg trots | op zijn dochter. | |

| Jan is very proud | of his daughter |

| c. | Marie stopt | Jan diep | onder de dekens. | |

| Marie puts | Jan deep | under the blankets |

Projections of the lexical heads may contain various elements that are not arguments or modifiers and thus do not affect the denotation of the head noun. Such elements simply provide additional information about the denotation. Examples of such functional categories are articles, numerals, and quantifiers, which we find in the nominal phrases in (21).

| a. | Jan is de/een | vroegere | vriend | van Peter. | article | |

| Jan is the/a | former | friend | of Peter |

| b. | Peter heeft | twee/veel | goede vrienden. | numeral/quantifier | |

| Jan has | two/many | good friends |

That functional categories provide additional information about the denotation of the lexical domain can be easily demonstrated by these examples. For example, the use of the definite article de in (21a) expresses that the (contextually determined) set denoted by the phrase vroegere vriend van Peter has a single member; the use of the indefinite article een, on the other hand, is compatible with there being more members in this set. Similarly, the use of the numeral tweetwo in (21b) expresses that there are exactly two members in the set, and the quantifier veelmany expresses that the set is large.

The functional elements found in verbal projections are tense (generally expressed as inflection on the finite verb) and complementizers. The semantic contribution of tense is that it provides information about the temporal location of the eventuality expressed by the lexical projection. The contribution of the complementizers in (22) concerns the illocutionary type of the expression: while dat in (22a) introduces embedded declarative clauses, ofwhether introduces embedded interrogative clauses.

| a. | Jan zegt [dat Marie ziek | is]. | declarative | |

| Jan says that Marie ill | is | |||

| 'Jan says that Marie is ill.' | ||||

| b. | Jan vroeg [of | Marie ziek | is]. | interrogative | |

| Jan asked whether | Marie ill | is | |||

| 'Jan asked whether Marie is ill.' | |||||

Since functional categories provide information about the lexical domain, they are often assumed to be part of a functional domain dominating (i.e. built on top of) the lexical domain; cf. (15) above. This functional domain is generally assumed to have a complex structure and to be highly relevant to word order: functional heads are assumed to project, just like lexical heads, thereby creating so-called specifier positions that can be used as landing sites for movement. A familiar case is wh-movement, which is assumed to target the specifier position in the projection of the complementizer; this explains why, in colloquial Dutch, wh-movement can result in the interrogative phrase being placed to the immediate left of the complementizer ofwhether. This is shown in (23b), where the trace t indicates the original position of the moved wh-element and the index i is just a convenient way to indicate that the two positions are related (i.e. to indicate that the wh-phrase is the direct object of the embedded clause). The discussion of word-order phenomena will therefore play a prominent role in the chapters devoted to the functional domain.

| a. | Jan zegt | [dat | Marie een boek van Louis Couperus | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| Jan says | that | Marie a book by Louis Couperus | read | has | ||

| 'Jan said that Marie has read a book by Louis Couperus.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan vroeg | [wati | (of) | Marie ti | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| Jan asked | what | whether | Marie | read | has | ||

| 'Jan asked what Marie has read.' | |||||||

While (relatively) much is known about the functional domain of verbal and nominal projections, research on the functional domain of adjectival and prepositional phrases is still in its infancy. For this reason, the reader will find separate chapters on this topic only in the parts on verbs and nouns.

The discussions of the four lexical categories will be concluded with a look at the external syntax of their projections, i.e. an examination of how such projections can be used in larger structures. For example, adjectives can be used as complementives (predicative complements of verbs), as attributive modifiers of noun phrases, and also as adverbial modifiers of verb phrases.

| a. | Die auto | is snel. | complementive use | |

| that car | is fast |

| b. | een | snelle | auto | attributive use | |

| a | fast | car |

| c. | De auto reed | snel | weg. | adverbial use | |

| the car drove | quickly | away | |||

| 'The car drove away quickly.' | |||||

Since the external syntax of the adjectival phrases in (24) can in principle also be described as the internal syntax of the verbal/nominal projections containing these phrases, this may lead to some redundancy. For example, complementives are discussed in Section V2.2 as part of the internal syntax of the verbal projection, but also in Sections N21.2, A28, and P35.2 as part of the external syntax of nominal, adjectival, and adpositional phrases. We have allowed this redundancy because it makes it possible to simplify the discussion of the internal syntax of verb phrases in V2.2: nominal, adjectival, and adpositional complementives behave differently in a number of ways, and discussing them all in Section V2.2 would have obscured the discussion of the properties of complementives in general. Of course, cross-references will inform the reader when a particular topic is discussed from the perspective of both internal and external syntax.

The idea for the SoD project was initiated by Henk van Riemsdijk in 1992. A pilot study was carried out at Tilburg University in 1993, and a steering committee was set up after a meeting with interested parties from Dutch and Flemish institutions. However, it took another five years before a substantial grant was received from the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (NWO) in 1998. In 2010, the SoD project became part of a larger project initiated by Hans Bennis and Geert Booij, called the Language Portal, which provides information on all aspects of the grammar (i.e. phonology, morphology and syntax) of three languages (Dutch, Frisian and Afrikaans). The first edition of SoD was published in 8 volumes by Amsterdam University Press in 2012-2019 as part of the linguistic series Comprehensive Grammar Resources, both in hardcover and as epubs in open access; SoD is also accessible via the Language Portal (https://taalportaal.org) on the internet.

1. H. Broekhuis, N. Corver and R. Vos: Verbs and verb phrases, Vol I-III

2. H. Broekhuis, E. Keizer and M. den Dikken: Noun and noun phrases, volume I-II

3. H. Broekhuis: Adjectives and adjective phrases

4. H. Broekhuis: Adpositions and adpositional phrases

5. H. Broekhuis and N. Corver: Coordination and ellipsis

The present, thoroughly revised, expanded and updated second edition of SoD was prepared by Hans Broekhuis during 2022-2025, under the supervision of Norbert Corver. To emphasize the unity of the work, it is now published under their general editorship to emphasize the unity of the work. It is again available in hardcover, as a free epub, and as part of the Language Portal (https://taalportaal.org).

Over the years, many Dutch linguists have commented on parts of the work presented here, and because we do not want to tire the reader with long lists of names, we simply thank the entire Dutch linguistic community, which also saves us the embarrassment of forgetting certain names. Nevertheless, we would like to make special mention of a number of people and institutions. The pilot study for the project, conducted from November 1993 to September 1994, was made possible by a grant from the Center for Language Studies and the University of Tilburg. This pilot study resulted in a project proposal, which was approved by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) in 1998 and enabled us to produce the main body of parts 2-4 mentioned in the previous subsection between May 1998 and May 2001. We would like to thank the members of the steering committee (chaired by Henk van Riemsdijk), which consisted of Hans Bennis, Martin Everaert, Liliane Haegeman, Anneke Neijt and Georges de Schutter, who all provided us with comments on substantial parts of the resulting manuscripts. The works in 2-4 could be prepared for publication between April 2008 and October 2010 thanks to a grant from the Truus und Gerrit van Riemsdijk-Stiftung: we are grateful to Carole Boster for copy-editing these works. Since November 2010, work on the SoD has continued at the Meertens Institute (KNAW) in Amsterdam as part of the Language Portal Dutch/Frisian project, again funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), which has enabled us to write the missing part on verbs and verb phrases. The Language Portal project was successfully completed with the presentation of the Language Portal in 2016. Since then, the Meertens Institute and Utrecht University have enabled Hans Broekhuis and Norbert Corver to continue their work on the SoD; this resulted in the additional volume on coordination and ellipsis, published in 2019, and now also in the publication of the second, completely revised edition of SoD. We are grateful for the financial and moral support of these institutions and thank them for the opportunity they have given us to develop the SoD. Special mention should be made of Frits Beukema, who meticulously proofread and edited the entire second edition and also provided us with valuable comments on the content of SoD; the remaining stylistic, grammatical, typographical, and formatting errors are due to changes made in the final stages of the revision process.

December 2025

Hans Broekhuis

Norbert Corver

Co-authors and editors of the Syntax of Dutch

References