- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section deals with adpositions like voorin front of and achterbehind, which denote sets of vectors. It will be shown that the denoted sets can be limited by using modifiers that restrict the orientation or the magnitude of the vectors.

Modifiers indicating the orientation of the located object with respect to the reference object are limited in number; we illustrate this here for the adposition achterbehind, but the results would be the same for the adposition voorin front of. The modifier rechtstraight in (6a) and the modifiers schuindiagonally and links/rechtsto the left/right in the (b)-examples are complementary in a sense: while the former restricts the set of vectors to those where x = 0, the latter exclude them. Note that we have topicalized the modified PPs in (6) to show unambiguously that the modifier and the PP form a constituent; cf. the constituency test.

| a. | Recht | achter Jan | zit | Marie. | |

| straight | behind Jan | sits | Marie | ||

| 'Marie is seated right behind Jan.' | |||||

| b. | Schuin | achter Jan | zit | Marie. | |

| diagonally | behind Jan | sits | Marie | ||

| 'Marie is seated diagonally behind Jan.' | |||||

| b'. | Links/Rechts | achter Jan | zit | Marie. | |

| left/right | behind Jan | sits | Marie | ||

| 'Marie is seated to the left/right behind Jan.' | |||||

The orientation modifiers in (7) could be called approximative, because they all express that the x-value of the vectors lies in between specific contextually determined norms. In other words, the vectors in the denotation set stay close to the y-axis; precies/exact emphasize that there is no deviation (x = 0), while the modifiers ongeveerabout and zowat ‘virtually; express that the deviation is negligible or at least small (x ≈ 0).

| a. | Precies/Exact | achter | Jan zit | Marie. | |

| precisely/exactly | behind | Jan sits | Marie | ||

| 'Marie is seated precisely behind Jan.' | |||||

| b. | Ongeveer/Zowat | achter | Jan zit | Marie. | |

| approximately/just.about | behind | Jan sits | Marie | ||

| 'Marie is seated more or less/just about behind Jan.' | |||||

The examples in (8) show that modifiers of orientation cannot be extracted from the adpositional phrase by wh-movement; we will see in Subsection II that they differ from modifiers of distance in this respect. The number signs are used to indicate that the examples are possible if recht and schuin are used to characterize Marie’s posture (i.e. whether she is sitting upright or not), which is not relevant here.

| a. | # | Hoe recht | zit | Marie voor/achter | Jan? |

| how straight | sits | Marie in.front.of/behind | Jan |

| b. | # | Hoe schuin | zit | Marie voor/achter | Jan? |

| how diagonally | sits | Marie in.front.of/behind | Jan |

It seems likely that the impossibility of extracting the modifier of orientation hoe recht/schuin is related to the fact that orientation modifiers, unlike distance modifiers, are not gradable; cf. the primeless examples in (9). Thus, it is the modification by hoehow and not the wh-extraction of the phrase hoe A that is excluded; this is supported by the primed examples in (9), which show that wh-movement of hoe recht/schuin is also excluded when it pied-pipes the whole PP.

| a. | # | Marie | zit | erg recht | voor/achter | Jan. |

| Marie | sits | very straight | in.front.of/behind | Jan |

| a'. | # | Hoe recht voor/achter Jan zit Marie? |

| b'. | # | Marie | zit | erg schuin | voor/achter | Jan. |

| Marie | sits | very diagonally | in.front.of/behind | Jan |

| b. | # | Hoe schuin zit Marie voor/achter Jan? |

The number signs in (9) again indicate that the examples are possible if recht and schuin describe Marie’s posture, in which case they function as supplementives modifying Marie; cf. also the examples in (14) and (15) below. This suggests that it is no coincidence that the adjectives recht and schuin can be used as modifiers of orientation, since they also denote orientations in their attributive and predicative uses. Consider the examples in (10a&b): in the case of rechtupright, the orientation of the tower is parallel to the vertical axis in the three-dimensional space diagram in Figure 4 below, whereas in the case of schuinleaning, the orientation deviates from this axis. Something similar applies to the adjectives links and rechts in (10c), although in these cases a reference object or reference point is always implied, which can be made explicit by adding a modifying van-PP.

| a. | De toren | staat | straight/scheef. | |

| the tower | stands | upright/leaning | ||

| 'The tower is straight/tilted.' | ||||

| b. | een | rechte/scheve | toren | |

| an | straight/leaning | tower | ||

| 'a straight/leaning tower' | ||||

| c. | Jan staat | links/rechts | (van de auto/in de foto). | |

| Jan stands | left/right | of the car/in the photo | ||

| 'Jan stands on the left/right side of the car/picture.' | ||||

Not all locational PPs denoting a set of vectors can be combined with the three types of modifiers in the examples in (6) and (7). Table 1 lists the relevant prepositions and indicates whether modification by orientation modifiers is possible or not. The percentage sign indicates that modification is blocked by pragmatic factors, and the number sign indicates that modification is possible but does not yield the intended reading; this will be discussed in the following discussion.

| preposition | translation | recht ‘straight’ | precies/ongeveer ‘exactly/approximately’ | schuin ‘diagonally’ |

| achter voor | behind in front of | + | + | + |

| boven onder | above under | + | + | + |

| naast links/rechts van | next to left/right of | % | % | % |

| buiten bij | outside near | — | — | — |

| om rond | around around | — | — | — |

| tegenover | opposite | + | + | + |

| langs | along | — | + | — |

| tussen | between | — | # | — |

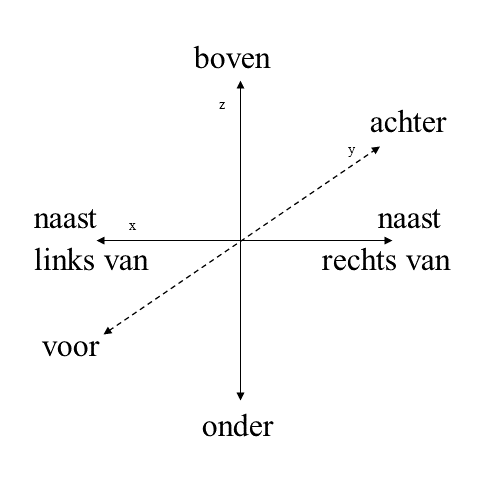

If we assume the Cartesian-style coordinate system in Figure 4 (cf. Section 32.3.1.2, sub II), we can conclude from Table 1 that at least the modifiers of orientation recht and schuin can only modify prepositions that refer to a single axis, i.e. to a single dimension in space. We will discuss this in more detail below.

The proposed constraint on the use of modifiers of orientation immediately accounts for the fact that voor/achter and onder/boven are amenable to modification because they refer to only a single axis (the z-axis and the y-axis, respectively). We would also expect modification of naast to be possible, but judgments on such examples are less clear. The primed examples in (11) have been given as grammatical in the literature, but for us they are certainly not as felicitous as the primeless examples with voor/achter and onder/boven: the primed examples seem to be unacceptable (11a') or severely marked (11b'&c'); note in passing that the intended meaning of (11c') can be expressed by (onmiddellijk) links/rechts van (immediately) to the left/right of.

| a. | Jan zit | recht | voor/achter | Marie. | |

| Jan sits | straight | in.front.of/behind | Marie |

| a'. | # | Jan zit | recht | naast | Marie. |

| Jan sits | straight | next.to | Marie |

| b. | Jan zit | schuin | voor/achter | Marie. | |

| Jan sits | diagonally | in.front.of/behind | Marie |

| b'. | # | Jan zit | schuin | naast | Marie. |

| Jan zits | diagonally | next.to | Marie |

| c. | Jan zit | links/rechts | voor/achter | Marie. | |

| Jan sits | left/right | in.front.of/behind | Marie |

| c'. | # | Jan zit | links/rechts | naast | Marie. |

| Jan sits | left/right | next.to | Marie |

We assign a number sign to the primed examples because their unacceptability may be due to pragmatic rather than to syntactic factors. This is especially true for the examples (11b'&c'); the intended meaning of these examples can in principle also be expressed by the corresponding primeless examples. Since the latter are more precise in the sense that they denote a smaller set of vectors, we may be dealing with a pragmatic blocking effect; according to Griceʼs maxim of quantity, the more precise and therefore more informative assertion is preferred to the less informative one.

The proposed constraint on the distribution of modifiers of orientation easily accounts for the fact indicated in Table 1 that modification of buiten and bij is excluded because they involve two axes (dimensions), viz. the x-axis and the y-axis; cf. Figure 21 in Section 32.3. Similarly, modification of om and rond is excluded because these also involve at least two axes; cf. the discussion of Figure 13C&D in Section 32.3.1.2, sub IIA. Modification of tegenover is possible because it refers to a subset of situations in which voor is applicable, and thus involves only a single axis; cf. the discussion of Figure 19 in Section 32.3.

| Het café | staat | recht/schuin | tegenover de kerk. | ||

| the bar | stands | straight/diagonally | opposite the church | ||

| 'The café is located directly/diagonally across from the church.' | |||||

The preposition langsalong is special in that the vectors it denotes do not have the same starting point (which actually also holds for the prepositions buiten and bij but in a less conspicuous way). Instead, the vectors are more or less parallel; cf. the discussion of Figure 20 in Section 32.3. Therefore, langs also involves more than one dimension, and modification by recht and schuin is correctly predicted to be excluded in (13a). Nevertheless, the use of the modifiers precies and ongeveer is possible in (13b); the two modifiers differ in that the former expresses that the garbage cans are placed in a neat line along the edge of the sidewalk, whereas the latter expresses that their arrangement is somewhat sloppier.

| a. | * | De vuilnisbakken | staan recht/schuin | langs de rand van de stoep. |

| the garbage.cans | stand straight/diagonally | along the edge of the sidewalk |

| b. | De vuilnisbakken | staan precies/?ongeveer | langs de rand van de stoep. | |

| the garbage.cans | stand exactly/approximately | along the edge of the sidewalk |

The preposition tussen deserves special treatment. The PP tussen de twee agentenbetween the two cops in (14a) can be preceded by the adjective recht. However, the meaning of recht differs from the intended meaning in that it does not modify the position of the located object Jan with respect to the reference objects de twee agenten, but refers to Jan’s posture: Jan is said to stand between the two agents and his posture is straight. In other words, recht is predicated of Jan and does not modify the PP; it is equivalent to the supplementive rechtopupright, which is not used as a modifier. That we are dealing with a supplementive and not a modifier is also clear from the fact that the AP can be used when the PP is not present, and from the fact that the AP can be topicalized in isolation, as shown in (14b).

| a. | Jan staat | recht/rechtop | (tussen de twee agenten). | |

| Jan stands | upright | between the two cops |

| b. | Recht/Rechtop | staat | Jan tussen de twee agenten. | |

| upright | stands | Jan between the two cops |

Since the same arguments can be repeated for the adjective schuin in (15), which has a similar function as the supplementive gebogenstooped, we can conclude that the modifiers recht and schuin cannot be used to modify a PP headed by tussen.

| a. | Jan staat | schuin/gebogen | (tussen de agenten). | |

| Jan stands | diagonally/stooped | between the cops |

| b. | Schuin/Gebogen staat Jan tussen de agenten. |

Modifying the PP with preciesexactly is possible, but then the modifier expresses that the distances from the located object and the relevant reference objects are all equal. Example (16a) expresses that the distance between the painting and candlestick 1 is equal to the distance between the painting and candlestick 2. Note that it is not necessary for the painting to be on the straight line between the two candlesticks; the painting can hang in the area above the candlesticks. The same is true for ongeveerapproximately; example (16b) only expresses that the distance between the painting and candlestick 1 is approximately the same as the distance between the painting and candlestick 2. We therefore conclude that PPs headed by tussen cannot be modified by modifiers of orientation; this means that the modifiers preciesexactly and ongeveerapproximately must have some other function, which is indicated by the use of the number sign in Table 1.

| a. | Het schilderij | hing | precies | tussen de twee kandelaars. | |

| the painting | hung | exactly | between the two candlesticks |

| b. | Het schilderij | hing | ongeveer | tussen de twee kandelaars. | |

| the painting | hung | approximately | between the two candlesticks |

We will conclude with two brief general remarks. First, example (17b) shows that the modifiers discussed in this subsection do not modify the preposition itself, but the whole PP. This is clear from the fact that, in the case of R-pronominalization, the R-word er can intervene between the modifier and the preposition. Note that the R-word can also precede the modifier, but this is not relevant here; it only shows that the R-word can undergo R-extraction to a PP-external position, as is usually the case with locational complementive PPs.

| a. | Het beeld staat | recht/schuin/precies | achter die zuil. | |

| the statue stands | straight/diagonally/exactly | behind that pillar | ||

| 'The statue is located straight/diagonally/exactly behind that pillar.' | ||||

| b. | Het beeld staat | <er> | [recht/schuin/precies [PP <er|> | achter]]. | |

| the statue stands | there | straight/diagonally/exactly | behind | ||

| 'The statue is located straight/diagonally/exactly behind it.' | |||||

Second, it can be observed that the degree of appropriateness of the use of two prepositions can be compared; example (18a) expresses that, as far as the orientation of the vector is concerned, both bovenabove and naastnext to seem to be applicable, but that boven is the more accurate term. Note that the set of vectors denoted by the adpositions must partially overlap: (18b) shows that antonymous adpositions, which by definition do not satisfy this condition, cannot be used in this construction. The number sign indicates that (18b) is acceptable if meer is interpreted as a frequency adverb with the same meaning as vakermore often; this is not relevant here.

| a. | De kogel | zit | meer | boven | dan | naast het hart. | |

| the bullet | sits | more | above | than | next.to the heart | ||

| 'The bullet is more above than beside the heart.' | |||||||

| b. | # | Jan zit | meer voor | dan achter | Marie. |

| Jan sits | more in.front.of | than behind | Marie |

While modifiers of orientation are always adjectival in nature, modifiers of distance (i.e. the modifiers of the magnitude of the vectors in the denoted set) can be either adjectival or nominal. This is shown in (19), where we have topicalized the modified PP in order to show unambiguously that the modifier and the PP form a constituent; cf. the constituency test. We will discuss the adjectival and nominal modifiers in separate subsections.

| a. | Hoog | boven de deur | hangt | een schilderij. | adjectival distance phrase | |

| high | above the door | hangs | a painting |

| b. | Twee meter | boven de deur | hangt | een schilderij. | nominal measure phrase | |

| two meter | above the door | hangs | a painting |

Adjectival modifiers are sensitive to the meaning of the modified PP. The adjectival modifier hooghigh in (19a), for example, can only modify PPs headed by bovenabove. Since the modification possibilities of locational PPs have not been investigated thoroughly in the literature so far, we restrict ourselves to the discussion of a limited set of modifiers: the pair diepdeep and hooghigh, which may amplify the antonymous adpositions boven and onder, the more or less antonymous pair dichtclose and verfar, which may amplify the adpositions bijnear and buitenoutside, and the adverbial modifiers vlak/palclose. Table 2 gives an overview of the modification possibilities, which will be discussed in more detail below.

| preposition | diep ‘deep’ | hoog ‘high’ | dicht ‘close’ | ver ‘far’ | vlak ‘close’ | pal ‘close’ | |

| achter voor | behind in front of | — | ? | — | + | + | + |

| boven onder | above under | — + | + — | — | % | + | + |

| naast links van rechts van | next to to the left of to the right of | — | — | — — — | % — — | + — | + — |

| buiten bij | outside near | — | — | — + | + — | % + | + % |

| om/rond | around | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| tegenover | opposite | — | — | — | — | % | — |

| langs | along | — | — | — | — | + | + |

| tussen | between | — | — | — | — | — | — |

We already mentioned above that the adjectival modifiers are sensitive to the meaning of the modified PP. Examples of this are given in (20): the modifier hooghigh is typically used with PPs headed by the preposition bovenabove, while the modifier diepdeep is typically used with the proposition onderunder. This more or less exhausts the possibilities of adjectival modification; although the adjectival modifier verfar is relatively common with these prepositions, it often seems to be the less preferred option; we have indicated this here with a question mark between brackets. Note that metaphorical examples of this sort are fully acceptable: cf. Hij scoorde ver boven het gemiddeldeHe scored well above average.

| a. | De ballon | hing | hoog/*diep/(?)ver | boven het huis. | |

| the balloon | hung | high/deep/far | above the house |

| b. | Amsterdam | ligt | diep/*hoog/(?)ver | onder de zeespiegel. | |

| Amsterdam | lies | deep/high/far | under the sea level |

However, the modifier ver can easily be used, and is often preferred, in metaphorically used locational constructions such as Dat gaat ver/??hoog boven mijn macht That is far beyond my power. Example (21a) illustrates the same point; the contrast with the syntactically parallel example in (21b) shows that the use of hoog is restricted to contexts of physical space.

| a. | Haar prestatie | steekt | ver/??hoog | boven | die van Jan | uit. | |

| her performance | sticks | far/high | above | that of Jan | out | ||

| 'Her performance is much better than Jan's.' | |||||||

| b. | De wolkenkrabber | steekt hoog/?ver | boven de andere huizen | uit. | |

| the skyscraper | sticks high/far | above the other houses | out | ||

| 'The skyscraper towers over the other houses.' | |||||

While the adjectival modifier verfar seems to be the lesser choice in case of a vertical (high-low) orientation, it is common in the horizontal (surface) orientation, where it forms an antonym pair with the adjective dichtclose. This is illustrated by the examples in (22). The two (b)-examples show that also in this case the choice of the adjectival modifier can be sensitive to the preposition heading the locational PP.

| a. | Jan zat | ver | voor/achter | de anderen. | |

| Jan sat | far | in.front.of./behind | the others |

| b. | Jan woont | ver/*dicht | buiten de stad. | |

| Jan lives | far/close | outside the city |

| b'. | Jan woont | dicht/*ver | bij de stad. | |

| Jan lives | close/far | near the city |

The acceptability of (22a) might lead us to expect that the adjectival modifier verfar can also be used with the preposition naastnext to, since this preposition also has a horizontal orientation, but example (23a) shows that this is not borne out. Again, there are a number of more or less idiomatic constructions, such as (23b), in which we are dealing with the discontinuous pronominal PP er ... naastnext to it. Note in passing that the primed (b)-example with the discontinuous pronominal PP er ... bijnear it is ambiguous between a literal reading “Jan came close to it (e.g. some physical goal)” and a metaphorical reading “Jan was nearly right (i.e. he came close to the right solution)”. Observe that the complementary distribution between ver and dicht found in the (b)-examples in (22) can also be observed in the (b)-examples in (23). Note further that the modifer dicht is perfectly acceptable when the adjective is modified with tetoo or genoegenough: cf. Jan zat er te dicht/dicht genoeg bij (om het goed te kunnen zien)Jan was too close/close enough (to see it clearly).

| a. | * | Jan zat | ver | naast | de anderen. |

| Jan sat | far | next.to | the others |

| b. | Jan zat er | ver/*dicht | naast. | |

| Jan sat there | far/close | next.to | ||

| 'Jan was completely wrong.' | ||||

| b'. | Jan kwam | er | dicht | bij. | |

| Jan came | there | close | near | ||

| 'Jan came close to it/Jan was nearly right.' | |||||

Another common case is the change-of-location construction in (24a) from sports jargon, where naast can also be used as an intransitive adposition; note that the antonym dicht cannot replace the modifier ver in this construction. Example (24b) shows that ver cannot be used as a modifier of locational PPs headed by the phrasal adpositions links/rechts van.

| a. | Jan schoot | de bal | ver/*dicht | naast (het doel). | |

| Jan shot | the ball | far/close | next.to the goal |

| b. | * | Jan schoot | de bal | ver/dicht | links/rechts | van het doel. |

| Jan shot | the ball | far/close | left/right | of the goal |

Ver can also modify naast-PPs when it is preceded by niet, as in (25a). Example (25b) shows that locational PPs headed by the phrasal adpositions links/rechts van do not have this modification possibility.

| a. | Niet ver/*dicht | naast de deur | zat de brievenbus. | |

| not far/close | next.to the door | sat the mailbox | ||

| 'The mailbox was close to the door.' | ||||

| b. | * | Niet ver/dicht | links/rechts | van de deur | zat de brievenbus. |

| not far/close | left/right | of the door | sat the mailbox |

Finally, the examples in (26) show that niet ver is also used in examples like (22b) and (23b), where the modifier dicht is expected but excluded.

| a. | Jan woont | niet ver/*dicht | buiten de stad. | |

| Jan lives | not far/close | outside the city | ||

| 'Jan lives not far outside the town.' | ||||

| b. | Jan zat er | niet ver/*dicht | naast. | |

| Jan sat there | not far/close | next.to | ||

| 'Jan was nearly right.' | ||||

The adjectival modifiers discussed in this subsection are used as degree amplifiers. This is consistent with the fact that adjectival downtoners are rare; cf. Section A25.1.2, sub IIB. The only seeming exception is the modifier dichtclose in (22b'), but this is because bijnear itself already indicates that the distance is short, and it is the shortness of the distance that is emphasized by the modifier dicht. In the remaining cases, the modifiers indicate that the distance between the located object and the reference object is great; there are no antonyms indicating that the distances are short, although the examples in (25) and (26) show that negation can be used to achieve a downtoning effect.

The fact that all the adjectival modifiers in (22) can be seen as amplifiers does not mean that downtoning is not possible. There is a small set of adverbs that can perform this function. Some examples are given in (27).

| a. | vlak/pal | achter | de deur | |

| close | behind | the door |

| b. | net | buiten | de stad | |

| just | outside | the city |

| c. | direct | boven | de deur | |

| directly | above | the door |

In the following, we will focus our discussion on the adverbs vlak and pal. As is shown in (28), these adverbial modifiers can be used with a wide range of locational prepositions; cf. also the last two columns of Table 2.

| a. | Jan zat | vlak/pal | voor/achter/naast de anderen. | |

| Jan sat | close | in.front.of/behind/next.to the others |

| b. | De ballon | hing | vlak/pal | boven het huis. | |

| the balloon | hung | close | above the house |

| b'. | Leiden ligt | vlak/pal | onder de zeespiegel. | |

| Leiden lies | close | under the surface of the sea |

| c. | Jan woont | pal/%vlak | buiten de stad. | |

| Jan lives | close | outside the city |

| c'. | Jan woont | vlak/%pal | bij de stad. | |

| Jan lives | close | near the city |

The percentage signs in the (c)-examples indicate that for some (but not all) speakers lexical restrictions may play a role: buiten in (28c) can only be modified by pal, while bij can only be modified by vlak. The markedness of vlak buiten de stad could also be due to a blocking effect, since the intended meaning of vlak buiten can also be expressed by vlak bijnear; the markedness of pal bij de stad in (28c') could then be due to the availability of dicht bijnear, which may be less obvious. It is not clear how widespread the indicated contrasts are, since all four combinations are common on the internet.

Table 2 shows that the adverbs vlak and pal can also modify locational PPs headed by langs, which cannot be modified by adjectival amplifiers. An example is given in (29a). If we want to express that the distance between the waterside and the houses is great, we have to use to the adjectival construction in (29b).

| a. | De huizen | staan | vlak/pal | langs de waterkant. | |

| the houses | stand | close | along the waterside |

| b. | De huizen | staan | ver | van de waterkant. | |

| the houses | stand | far | from the waterside |

It is not immediately clear whether tegenoveropposite can be modified for distance by the adverb pal: in this context, pal in (30a) seems to be more or less equivalent to the modifier of orientation rechtstraight in (12), an interpretation that is also possible in the case of voor in (30b). Examples with the adverb vlak in the intended distance reading are fairly common on the internet but marked for some speakers. We conclude that PPs headed by tegenover are somewhat restricted with respect to modification for distance.

| a. | Het café | staat | #pal/%vlak | tegenover | de kerk. | |

| the bar | stands | frontally/close | opposite | the church |

| b. | Het café | staat | pal/recht | voor | de kerk. | |

| the bar | stands | frontally/straight | in.front.of | the church |

The remaining prepositions om/rond and tussen do not seem to allow modification by pal and vlak, with the notable exception of vlak/pal om de hoekjust around the corner.

A difference between the adjectival modifiers like diepdeep, hooghigh, dichtclose and verfar and the adverbs vlakclose and palclose is that the first are gradable (i.e. they can be modified and undergo comparative/superlative formation), whereas the latter are not. This is shown for dicht bij and vlak bij in (31).

| a. | Jan woont | heel | dicht/*vlak | bij de stad. | |

| Jan lives | very | close near | the city |

| b. | Jan woont | dichter/*vlakker | bij de stad | (dan Marie). | |

| Jan lives | closer | near the city | than Marie |

| c. | Jan woont | het | dichtst/*vlakst | bij de stad. | |

| Jan lives | the | closest | near the city |

Like all gradable adjectives, dicht can also be questioned. As shown in (32a), the modifier can then be extracted from the PP and be moved into the sentence-initial position. Since the adverbs vlak and pal are not gradable, they cannot be questioned; this is shown in (32b) for vlak.

| a. | Hoe dichti | woont | Jan ti | bij de stad? | |

| how close | lives | Jan | near the city |

| b. | * | Hoe vlaki | woont | Jan ti | bij de stad? |

| how close | lives | Jan | near the city |

Finally, it should be noted that the modifiers in (31a) do not modify the preposition itself, but the whole PP. This is clear from the fact, illustrated in in (33b), that in the case of R-pronominalization, the R-word er can intervene between the modifier and the preposition.

| a. | De boom | stond | dicht/vlak | bij het huis. | |

| the tree | stood | close | near the house | ||

| 'The tree stood close to the house.' | |||||

| b. | De boom | stond [dicht/vlak [PP | er | bij]]. | |

| the tree | stood close | there | near | ||

| 'The tree stood close to it.' | |||||

Example (33b) also shows that dicht bij and vlak bij cannot be considered compounds. The same may be true for cases where dicht and vlak combine with an intransitive adposition, contrary to what the orthographic convention of writing dichtbij and vlakbij in such cases suggests, but we leave this open for future discussion; cf. taaladvies.net/vlakbij-of-vlak-bij-de-school/.

Any nominal phrase that can be used to measure distance can be used as a modifier to express the exact magnitude of the vectors involved. Some examples with the nominal measure phrase twee (kilo)metertwo (kilo)meters are given in Table 3, which shows that the locational prepositions can be divided into two groups based on whether or not they can be modified by such phrases.

| preposition | example | translation |

| achter voor | twee meter achter het doel twee meter voor het doel | two meters behind the goal two meters in front of the goal |

| boven onder | twee meter boven de deur twee meter onder de grond | two meters above the door two meters under the ground |

| naast links van rechts van | twee meter naast de paal ?twee meter links van de deur ?twee meter rechts van de deur | two meters beside (next to) the pole two meters to the left of the door two meters to the right of the door |

| buiten bij | twee kilometer buiten de stad *twee kilometer bij de stad | two kilometers outside the town *two kilometers near the town |

| om rond | — | |

| tegenover | — | |

| langs | — | |

| tussen | — |

Note that the primeless examples in (34) are acceptable, but in such examples the nominal phrase does not modify the magnitude of the vectors involved, which is clear from the fact that the locational PP can be omitted without changing the core meaning of the sentence. Instead, the noun phrase functions as a complement to the motion verb and refers to the distance that has been traveled by the subject of the clause. That the noun phrase does not modify the PP but is selected by the motion verb is also clear from the fact that the primed examples with a location verb are not acceptable.

| a. | Jan liep | twee kilometer | (rond de stad). | |

| Jan walked | two kilometer | around the city |

| a'. | De huizen | stonden | *(twee kilometer) | rond de stad. | |

| the houses | stood | two kilometers | around the city |

| b. | Jan liep | twee kilometer | (langs het kanaal). | |

| Jan walked | two kilometers | along waterway |

| b'. | Het huis | stond | *(twee kilometer) | langs het kanaal. | |

| the house | stood | two kilometer | along the waterway |

Nominal measure phrases are like the adjectival modifiers in that they can be extracted from the PP and be placed in the sentence-initial position in interrogative clauses, as illustrated in (35); cf. Corver (1990).

| a. | Hoeveel kilometeri | ligt | jouw huis [PP ti | buiten de stad]? | |

| how.many kilometers | lies | your house | outside the city |

| b. | Hoeveel meteri | ligt | Amsterdam [PP ti | onder de zeespiegel]? | |

| how.many meters | lies | Amsterdam | under the surface of the sea |

The examples in (36) show that the measure phrases do not modify the preposition itself but the full PP: in case of R-pronominalization, the R-word er can intervene between the modifier and the preposition.

| a. | Jan viel | drie meter | voor de eindstreep | op de grond. | |

| Jan fell | three meters | in.front.of the finish line | on the ground | ||

| 'Three meters from the finish line, Jan fell to the ground.' | |||||

| b. | Jan viel | [drie meter [PP | er | voor]] | op de grond. | |

| Jan fell | three meters | there | in.front.of | on the ground | ||

| 'Three meters in front of it, Jan fell to the ground.' | ||||||

The previous subsections have discussed the modification possibilities of locational PPs headed by prepositions denoting vector sets; they have shown that such PPs can be divided into three groups. The first group consists of PPs headed by prepositions that relate to a single axis of the coordinate system in Figure 4; the PPs in this group can be easily modified by modifiers of orientation and modifiers of distance. The second group consists of PPs headed by the prepositions buiten and bij, which can be modified by modifiers of distance (with a possible lexical restriction on the choice between the adverbs vlak and pal; cf. (28c&c')), but not by modifiers of orientation. The remaining locational PPs make up a third group, which can be modified neither for orientation nor for distance; exceptions are PPs headed by tegenover, which can be modified by modifiers of orientation like rechtstraight and schuindiagonally, and PPs headed by langs, which can be modified by adverbial modifiers of distance like vlak and pal. These results are summarized in Table 4.

| preposition | translation | orientation | distance | ||

| adjectival modification | adjectival modification | vlak/pal ‘close’ | nominal modification | ||

| achter voor | behind in front of | + | + | + | + |

| boven onder | above under | + | + | + | + |

| naast links van rechts van | next to to the left of to the right of | % | — | + — — | + |

| buiten/bij | outside/near | — | + | + | + |

| om/rond | around | — | — | — | — |

| tegenover | opposite | + | — | — | — |

| langs | along | — | — | + | — |

| tussen | between | — | — | — | — |