- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Section 9.2 has shown that finite verbs occupy the second position in main clauses; they can be preceded by at most one constituent, which is usually the subject of the clause. However, in declarative clauses it can also be a topicalized phrase, and in wh-questions it is an interrogative phrase. Note that the traces ti in (31) are used to indicate the (presumed) base position of the clause-initial constituents

| a. | Mijn zusteri | heeft | ti dit boek | gelezen. | subject-initial | |

| my sister | has | this book | read | |||

| 'My sister has read this book.' | ||||||

| b. | Dit boeki | heeft | mijn zuster ti | gelezen. | topicalization | |

| this book | has | my sister | read | |||

| 'This book, my sister has read.' | ||||||

| c. | Welk boeki | heeft | mijn zuster ti | gelezen? | wh-question | |

| which book | has | my sister | read | |||

| 'Which book has my sister read?' | ||||||

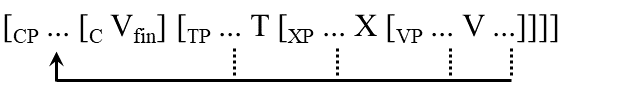

The highly simplified representations in (31) reflect the more traditional generative analysis, according to which they all involve the movement of some constituent from a clause-internal position into the specifier of CP, i.e. the left-peripheral position preceding the finite verb in the C-position in the structure in (32). Assuming that the specifier positions of all projections (here the positions immediately to the left of the heads C, T, X, and V) can contain at most one constituent, we derive the verb-second effect.

|

The following subsections briefly discuss the three construction types in (31), both in main clauses and in embedded clauses. This discussion will lead to a revised version of the proposal in (32).

There are two types of questions: so-called yes/no questions, such as (33a), which require the addressee to provide the speaker with information about the truth of the proposition expressed by the clause, and wh-questions, such as (33b), which require the addressee to provide the speaker with some missing piece of information related to the proposition. The clause-initial position of yes/no questions remains phonetically empty (although we will see in the discussion of the examples in (35) below that it is presumably lexically filled by a phonetically empty question operator). In wh-questions, the wh-phrase is usually moved into the clause-initial position.

| a. | Heeft | mijn zuster | dit boek | gelezen? | yes/no question | |

| has | my sister | this book | read | |||

| 'Has my sister read this book?' | ||||||

| b. | Wanneer | heeft | mijn zuster | dit boek | gelezen? | wh-question | |

| when | has | my sister | this book | read | |||

| 'When did my sister read this book?' | |||||||

The hypothesis in (32) that the wh-phrase is moved into the specifier of the CP leads to the prediction that wh-phrases also precede the C-position in embedded questions. Although in the more formal registers complementizers are not normally realized phonetically in embedded wh-questions, this is easily possible in colloquial speech. Example (34a) first shows that embedded yes/no questions differ from embedded declarative clauses in that the complementizer does not have the form datthat but the form ofwhether. The (b)-examples in (34) show that this complementizer can also be realized optionally in embedded wh-questions and then, as predicted, must follow the wh-phrase in the clause-initial position. Note that in some regional varieties of Dutch the complementizer of finds an alternative realization as of dat or dat; cf. Barbiers (2008: §1.3.1.5). For the question whether of dat should be analyzed as a compound or as two separate words, see Hoekstra & Zwart (1994), Sturm (1996) and Zwart & Hoekstra (1997).

| a. | Jan vroeg [CP | of [TP | mijn zuster | dit boek | gelezen | heeft]]. | yes/no question | |

| Jan asked | comp | my sister | this book | read | has | |||

| 'Jan asked whether my sister has read this book.' | ||||||||

| b. | Jan vroeg [CP | wiei | (of) [TP ti | dit boek | gelezen | heeft]]. | wh-question | |

| Jan asked | who | comp | this book | read | has | |||

| 'Jan asked who has read this book.' | ||||||||

| b'. | Jan vroeg [CP | wati | (of) [TP | mijn zuster ti | gelezen | heeft]]. | wh-question | |

| Jan asked | what | comp | my sister | read | has | |||

| 'Jan asked what my sister has read.' | ||||||||

Now consider example (35a), but ignore the additional trace t'i, which we will return to shortly. This example shows that wh-movement does not necessarily target the clause-initial position of the embedded clause, but that it is also possible to move a wh-phrase from the embedded clause into the initial position of some higher clause, here the main clause. This form of so-called long wh-movement is excluded, however, if the embedded clause is itself an embedded question: examples (35b&c) show that both yes/no and wh-questions constitute so-called islands for wh-extraction from the embedded clause. Note that some speakers report a slight contrast in acceptability between the two examples, with (35b) being slightly less degraded than (35c), but both cases are quite bad for most speakers.

| a. | Wati | denk | je [t'i | dat | mijn zuster ti | gelezen | heeft]? | |

| what | think | you | comp | my sister | read | has | ||

| 'What do you think that my sister has read?' | ||||||||

| b. | * | Wati | vroeg Jan | [of | mijn zuster ti | gelezen | heeft]]? |

| what | asked Jan | comp | my sister | read | has |

| c. | * | Watj | vroeg Jan [CP | wiei | (of) [TP ti tj | gelezen | heeft]]? |

| what | asked Jan | who | comp | read | has |

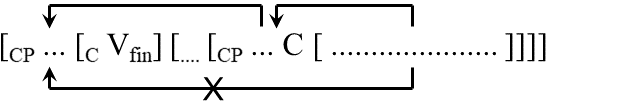

The examples in (35) are usually taken to show that wh-phrases originating from embedded clauses cannot be moved into the sentence-initial position in one fell swoop; they can only be extracted from their clause via the specifier position of its CP, which thus functions as an “escape hatch”. This means that long wh-movement should be reinterpreted as a series of clause-bound movements; cf. the schematic representation in (36), and Chomsky (1977) for detailed discussion. The claim is that this escape hatch is only available when the embedded clause is declarative, as in (35a), where the intermediate trace t'i is left by the movement through the escape hatch. The reason why the specifier of CP cannot be used as an escape hatch in the case of embedded questions like (35b&c) is that the specifier of CP is syntactically filled by a phonetically empty question operator in yes/no questions, and by another interrogative phrase in wh-questions; this makes it impossible for the wh-object watwhat to use the specifier of CP as an escape hatch from its clause.

|

Since this will become relevant in the following subsections, we conclude here by noting that Dutch shows a marked difference from English in that wh-subjects can be extracted from embedded clauses introduced by a complementizer, as illustrated in (37); cf. Bennis (1986: §3). Consider the examples in (37).

| a. | Wiei | denk | je [t'i | dat | *(er) ti | komt]? | |

| who | think | you | that | there | comes | ||

| 'Who do you think (*that) is coming?' | |||||||

| b. | Wiei | denk | je [t'i | dat | (er) ti | dit boek | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| who | think | you | that | there | this book | read | has | ||

| 'Who do you think (*that) has read this book?' | |||||||||

| c. | Wiei | denk | je [t'i | dat | (*er) ti | het | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| who | think | you | that | there | it | read | has | ||

| 'Who do you think (*that) has read this book?' | |||||||||

The acceptability of extraction of wh-subjects seems to depend on (interrelated issues regarding) the distribution of the expletive er and information structure. The obligatory presence of expletive er in (37a) indicates that the embedded clause expresses only discourse-new information, and subject extraction is possible. However, when the embedded clause contains presuppositional material, such as the object pronoun hetit in (37c), the expletive er cannot be used and subject extraction is impossible. This contrast may be related to the complementizer-trace filter proposed in Chomsky & Lasnik (1977), which states that overt complementizers cannot be immediately followed by a subject trace: this filter is satisfied in (37a), because the expletive is arguably located between the complementizer and the trace, but not in (37c), where the expletive cannot be used. A problem with this filtering approach is that (37b) is acceptable regardless of the presence of the expletive. However, since the definite object dit boekthis book can be interpreted as discourse-new information, again regardless of the presence of the expletive, we can conclude that the acceptability of wh-subject extraction is completely determined by the information structure of the embedded clause. Since Section 13.2, sub IC, will argue that the information structure determines whether a non-presuppositional subject must be moved into the canonical subject position of the clause or can remain in its base position in the lexical domain, this means that we can ultimately appeal to the syntactic position from which the subject is wh-moved; wh-movement across the complementizer is possible from its base position within the lexical domain, but not from the canonical subject position (i.e. the specifier of TP).

Topicalization is typically restricted to main clauses in standard Dutch. The examples in (38) show that it is excluded in embedded clauses, regardless of whether the complementizer is phonetically realized or whether the topicalized phrase precedes or follows the declarative complementizer.

| a. | * | Jan zei [CP | dit boeki | (dat) | [mijn zuster ti | gelezen | had]]. |

| Jan said | this book | comp | my sister | read | has |

| b. | * | Jan zei [CP | (dat) | dit boeki | mijn zuster ti | gelezen | had]]. |

| Jan said | comp | this book | my sister | read | had |

The fact that topicalization is not possible in embedded clauses in standard Dutch is clearly related to the fact that it also does not allow verb-second in embedded clauses: German, as well as a large subset of the Dutch varieties that do allow embedded verb-second, also allow embedded topicalization: cf. Haider (1985/2010) for German and Barbiers (2008: §1.3.1.8) for the relevant non-standard Dutch varieties. Note also that Dutch topicalization seems to be quite different from English topicalization, which can lead to English examples of the type in (38b): cf. I believe that this book, you should read, taken from Lasnik & Saito (1992:76).

The cases in (39) show that although topicalization is not possible within embedded clauses, it is possible to topicalize constituents from embedded clauses by placing them into the main-clause initial position. The fact that example (39a) is possible (though perhaps somewhat marked) shows again that subjects can be extracted from embedded declarative clauses introduced by a complementizer.

| a. | Mijn zusteri | zei | Jan [t'i | dat ti | dit boek | gelezen | had]. | |

| my sister | said | Jan | comp | this book | read | had |

| b. | Dit boeki | zei | Jan [t'i | dat | mijn zuster ti | gelezen | had]. | |

| this book | said | Jan | that | my sister | read | has |

The examples in (40) show that topicalization is impossible when the embedded clause is interrogative; this suggests that, as in the case of question formation, topicalization of an element from the embedded clause into the main-clause initial position must proceed via the specifier position of the embedded CP; cf. the schematic representation in (36).

| a. | * | Mijn zusteri | vroeg | Jan zich | af | [welk boekj (of) ti tj | gelezen | had]. |

| my sister | wondered | Jan refl | prt. | which book comp | read | had |

| b. | * | Dit boekj | vroeg | Jan zich | af | [wiei (of) ti tj | gelezen | had]. |

| this book | wondered | Jan refl | prt. | who comp | read | has |

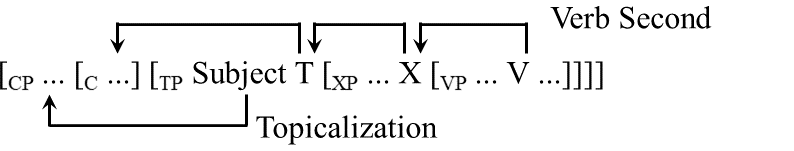

The representation in (41b) sketches the standard generative analysis of subject-initial declarative main clauses such as (41a). First, it is assumed that the specifier position of TP is the canonical subject position; it is the position in which the subject is traditionally taken to be assigned nominative case by the feature [+finite] of T. Second, since verb-second places the finite verb in C and C precedes the regular subject position, the subject must be topicalized into the specifier of CP in order to precede the finite verb.

| a. | Mijn zuster/Zij/Ze | had dit boek | gelezen. | |

| my sister/she/she | had this book | read | ||

| 'My sister/she had read this book.' | ||||

| b. |  |

Note in passing that we accept the widely supported claim (from Travis 1984:131) that the verb moves to C via all intermediate head positions, for which reason we will henceforth speak of V-to-C, V-to-T, V-to-X, etc. Verb movement via the intermediate T-position is generally motivated by saying that this movement can be triggered by the tense and/or agreement features in this position. The movement of the verb via the (as yet undetermined) X-position depicted in (41b) is provided for theory-internal reasons, but need not concern us now; for this reason, we will not include this movement in the representations in Subsection IV; the availability of V-to-C, however, will become crucial in the discussion given there.

If the derivation in (41b) were correct, we would expect the placement of subjects to be subject to similar restrictions as regular topicalization. At first sight, this expectation seems to be borne out, since Subsection II has already shown that embedded subjects such as mijn zustermy sister can be placed in main-clause initial position; cf. (42a). However, this is not always possible, as weak pronominal subjects show a conspicuously different behavior; the examples in (42b&c) show that although topicalization of embedded subject pronouns seems possible when they are strong (i.e. phonetically non-reduced) and contrastively stressed, it is clearly excluded when they are weak (phonetically reduced).

| a. | Mijn zusteri | zei | Jan [t'i | dat ti | dit boek | gelezen | had]. | |

| my sister | said | Jan | comp | this book | read | had |

| b. | (?) | Ziji | zei | Jan [t'i | dat ti | dit boek | gelezen | had]. |

| she | said | Jan | comp | this book | read | had |

| c. | * | Zei | zei | Jan [t'i | dat ti | dit boek | gelezen | had]. |

| she | said | Jan | comp | this book | read | had |

Thus, the topicalization behavior of subject pronouns seems to be very similar to that of object pronouns: whereas strong object pronouns allow topicalization when they are contrastively stressed, weak object pronouns do not; cf. Huybregts (1991). However, it may be that the contrast found in (42) is not due to a restriction on topicalization as such, but rather to restrictions on subject extraction of a similar kind as briefly discussed in Subsection I. Moreover, we still have to deal with the fact, illustrated again in (43), that weak subject pronouns of main clauses are perfectly acceptable in sentence-initial position, unlike weak object pronouns.

| a. | Marie/Ze | heeft | Peter/hem/ʼm | gekust. | |

| Marie/she | has | Peter/him/him | kissed |

| b. | Peteri/Hemi/*ʼmi | heeft | Marie/ze ti | gekust. | |

| him/him/him | has | Marie/she | kissed |

This acceptability contrast suggests that the topicalization approach to subject-initial clauses may not be entirely correct; therefore, we will consider an alternative approach in the following subsection.

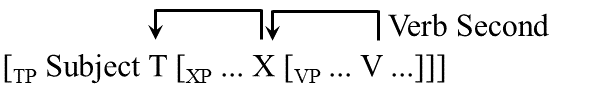

The contrast between weak subject and object pronouns in example (43) suggests that the standard assumption that subject-initial sentences are derived by topicalization of the subject is not correct, because weak pronouns cannot be topicalized. However, if we adopt the structure in (10), repeated in a slightly revised form in (44), we can easily account for this contrast by assuming that subject-initial main clauses are not CPs but TPs (which is the traditional assumption for English); the CP-layer is added only when needed to accommodate wh-moved elements; cf. Grimshaw (1997).

| [CP ... C [TP Subject T [XP ... X [VP ... V ...]]]] |

The verb-second property of Dutch can then be derived by assuming the analyses in (45); cf. Travis (1984) and Zwart (1997). The V-to-T movement (via X) in the subject-initial sentence in (45a) can be motivated by appealing to the earlier assumption that T contains the tense and/or agreement features of the verb. The subsequent T-to-C movement of the verb to the C-position in (45b) can be motivated by the standard assumption that C contains certain (e.g. illocutionary) features. By assuming that declarative force is assigned as a default value, the absence of the CP-layer in subject-initial clauses such as (45a) can also be explained.

| a. | Subject-initial sentence |

|

| b. | Topicalization and question formation |

|

Obviously, the analysis in (45) raises the question why the verb does not move to T in embedded clauses, resulting in a word order (found in English) in which the subject is sandwiched between the complementizer and the finite verb: *dat mijn broer heeft dit boek gelezen. The assumption that verb movement is forced by the language-specific surface condition that the highest functional head in an extended projection must be lexically filled would solve this. It predicts that when the C-position is filled by the complementizer, the verb can remain in its original position within the lexical domain. If this assumption is acceptable, verb movement can be functionally motivated by saying that every clause must be marked as such by a complementizer or a finite verb in second position. Since further discussion would lead us too deep into theoretical argumentation, we will not elaborate here, but refer the reader to Zwart (2001) and Broekhuis (2008: §4.1) for further discussion.

Accepting the two structures in (45) would make it possible to account for the contrast in verbal inflection in the examples in (46) by making the form of the finite verb sensitive to the position it occupies; if the verb is in T, as in (46a), the second-person singular agreement is realized by a -t ending, but if it is in C, as in (46b&c), it is realized by a null morpheme.

| a. | Jij/Je | loop-t | niet | erg snel. | |

| you/you | walk-2sg | not | very fast | ||

| 'You do not walk very fast.' | |||||

| b. | Erg snel | loop-Ø | jij/je | niet. | |

| very fast | walk-2sg | you/you | not | ||

| 'You do not walk very fast.' | |||||

| c. | Hoe snel loop-Ø | jij/je? | |

| how fast walk-2sg | you/you | ||

| 'How fast do you walk?' | |||

Given that Dutch has such morphological alternations only with second-person singular subjects, we will not digress on this point here, but refer the reader to Zwart (1997), Postma (2011), and Barbiers (2013) for a discussion of language varieties that more generally exhibit similar inflectional contrasts.

This section has discussed the clause-initial position, which can be filled by wh-movement in questions and topicalization constructions. However, the two cases differ in that wh-movement always targets the sentence-initial position in the case of topicalization, while it can also target the clause-initial position of embedded questions. Traditionally, subject-initial main clauses have also been analyzed as topicalization constructions; the verb is moved to the C-position of the clause and the subject must therefore subsequently be moved into the specifier of the CP. However, the fact that topicalization of weak (phonetically reduced) pronouns is normally not possible casts doubt on this view, since weak subject pronouns can easily occur sentence-initially, leading to the claim that subject-initial main clauses are TPs, not CPs (as usually assumed for English).