- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This chapter takes as its starting point the discussion in Section 9.2, which has shown that finite verbs can be found in basically two positions: the clause-final verb position in embedded clauses and the verb-first/second position in main clauses; the latter position is usually occupied by a complementizer in embedded clauses.

| a. | Marie zegt | [dat | Jan | het boek | leest]. | clause-final position | |

| Marie says | that | Jan | the book | reads | |||

| 'Marie says that Jan is reading the book.' | |||||||

| b. | Op dit moment | leest | Jan het boek. | verb-second position | |

| at this moment | reads | Jan the book | |||

| 'Right now, Jan is reading the book.' | |||||

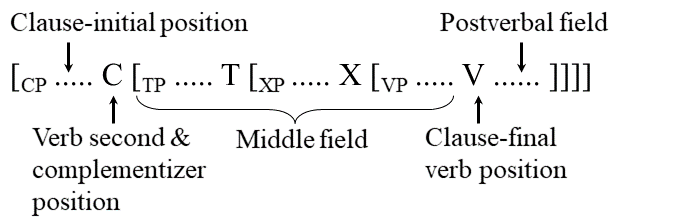

On the basis of these two positions, the clause is traditionally divided into three topological fields: the clause-initial position, the middle field, and the postverbal field. This is illustrated in Figure (2), repeated from Section 9.2.

|

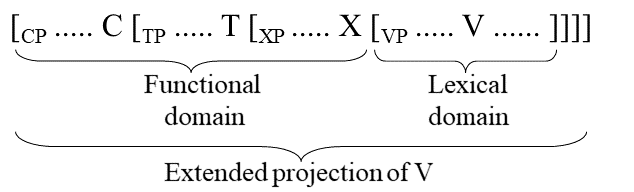

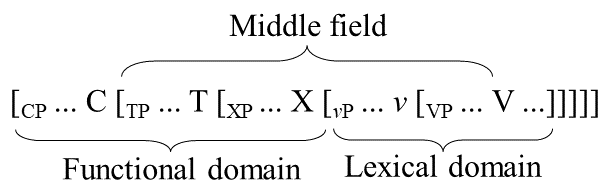

This chapter will focus on the middle field of the clause. Section 9.1 has shown, however, that this notion has no independent theoretical status, as it cuts across the more fundamental division between the lexical and the functional domain of the clause.

|

The lexical domain of the clause consists of the main verb and its arguments and VP modifiers, which together form a proposition. For example, the verb kopento buy in (4a) takes the noun phrase het boekthe book as complement and is then modified by the manner adverb snelquickly, and the resulting complex predicate is finally predicated of the noun phrase Jan. The complex phrase thus formed expresses the proposition that can be represented by the logical formula in (4b).

| a. | [Jan | [snel | [het boek | kopen]]] | |

| Jan | quickly | the book | buy |

| b. | buy quickly (Jan, the book) |

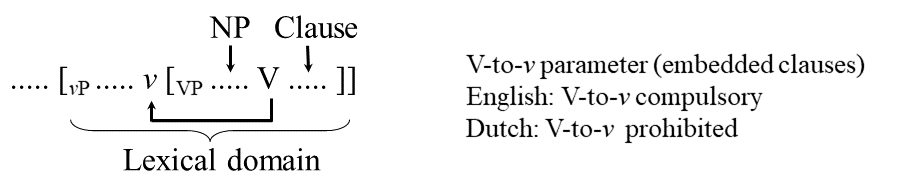

If the proposition in (4b) is to correspond to the syntactic structure in (4a), we should conclude that the VP in (3) must be replaced by a more finely articulated syntactic structure. Current generative research generally assumes that this structure is as given in (5). Since the linking of semantic and syntactic structure is unlikely to vary across languages, it is often assumed that the structure in (5) is more or less invariant across languages, and that surface differences between languages are due to movement. For example, the difference in word order between Dutch and English with respect to the relative placement of the verb and the nominal direct object can be explained by assuming that English, but not Dutch, has obligatory V-to-v movement; cf. Section 9.4 for a more detailed discussion.

|

The structure in (4a) can now be made more explicit as in (6): internal arguments such as the theme het boekthe book are generated within the VP, VP adverbials such as the manner adverb snelquickly are adjoined to the VP, and external arguments such as the agent Jan are generated as the specifier of the light verb v (where the term light is used to indicate that v has syntactic features but little or no meaning).

| [vP | Jan v [VP | snel [VP | het boek | kopen]]] | ||

| [vP | Jan | quickly | the book | buy |

In the following we will assume that the lexical domain of the clause has a more finely articulated structure, and we will therefore replace the global representation of the clause in structure (3) with the one in (7). Note that the lexical domain may be even more complex than indicated here, since we have ignored issues raised by structures with e.g. indirect objects or complementives.

|

The semantic information encoded in the lexical domain can be equated with the information expressed by traditional predicate calculus; the functional domain provides additional information. For example, the functional head T in (7) adds the tense feature [±past], and the functional head C indicates illocutionary force, as can be seen from the fact that the complementizers datthat and ofif/whether introduce embedded declarative and interrogative clauses, respectively. Section 13.3 will show that there may be other functional heads besides T and C, indicated by X in (7); these introduce other semantically (and also syntactically) relevant features, such as negation. For now, it is important to recall that Section 10.1 has shown that in main clauses finite verbs are moved from the lexical domain into the functional head C (or T), which explains the verb-first/second effect in Dutch.

Although arguments, complementives and VP adverbials generally appear in the lexical domain of the clause, they can also be moved into the functional domain. Usually this has a semantic motivation; Section 11.3.1 has shown, for example, that wh-phrases are moved into the clause-initial position in order to create structures such as (8a), which can be translated more or less directly into the logical formula in (8b): the interrogative pronoun wat in the clause-initial position corresponds to the question operator ?x, while the trace of the wh-phrase corresponds to the variable x.

| a. | Wati | leest | Peter ti? | |

| what | reads | Peter | ||

| 'What is Peter reading?' | ||||

| b. | ?x (Peter is reading x) |

In main clauses, the effect of wh-movement is immediately obvious from the fact that the wh-phrase appears in the position preceding the finite verb. Movements that target a clause-internal position are often less easy to observe. For example, in passive constructions it is usually assumed that the internal theme argument moves from its original VP-internal position into the regular subject position, the specifier position of TP in (7), but this can only be observed if there is other material between the two positions. This is illustrated by the passive example in (9b), which shows that the postulated movement is indeed possible in Dutch, but optional if the derived subject is definite. Of course, it is less easy to determine whether or not the movement applies when the indirect object is left implicit; in this case, the effect of movement cannot be observed directly from the word order of the clause.

| a. | dat | de gemeente | (de koning) | het concert | aanbood. | active | |

| that | the municipality | the king | the concert | prt-offered | |||

| 'that the municipality offered the king the concert.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | <het concert> | (de koning) <het concert> | aangeboden | werd. | passive | |

| that | the concert | the king | prt-offered | was | |||

| 'that the concert was offered to the king.' | |||||||

In order to be able to test whether movement from the lexical to the functional domain has taken place, we need a demarcation of the boundary between the two domains, called pivot location in Haeseryn et al. (1997:1328) and comment modifier in Verhagen (1986: §4). clause adverbials such as the modal waarschijnlijkprobably can perform this function because they take scope over the proposition expressed by the vP in (7); in terms of logic, the modal adverbial waarschijnlijk functions as a logical operator taking scope over proposition p: ◊p. This fact underlies the standard adverbial test according to which clause adverbials can be paraphrased by the construction Het is adverb zo dat ... it is adverb so that ..., in which the adverb also has scope over the proposition expressed by the embedded clause; cf. Section 8.1.

| a. | Jan werkt | waarschijnlijk. | |

| Jan works | probably | ||

| 'Jan is probably working.' | |||

| b. | Het | is waarschijnlijk | zo | dat | Jan werkt. | |

| it | is probably | the.case | that | Jan works | ||

| 'It is probably the case that Jan is working.' | ||||||

Another argument in favor of the assumption that modal adverbials (including certain particles such as modal toch) mark the boundary between the lexical and the functional domain is the fact, illustrated in (11), that they can precede an external argument, which is located at the left edge of the lexical domain of the clause, namely in the specifier of the light verb v in (5)/(7).

| dat [TP | <de klant> | waarschijnlijk [vP <de klant> v [VP | het boek | koopt]]]. | ||

| that | the customer | probably | the book | buys | ||

| 'that the customer will probably buy the book.' | ||||||

Example (11) shows that the movement of the subject into the regular subject position is not only optional in passive constructions such as (9b), but also in active constructions. We will return to this fact in Section 13.2, where it will be shown that the movements indicated in (12), called subject shift because they affect a noun phrase appearing as the nominative subject, are restricted by the information structure of the clause; they apply only when the subject provides discourse-old information.

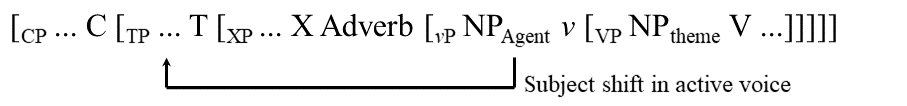

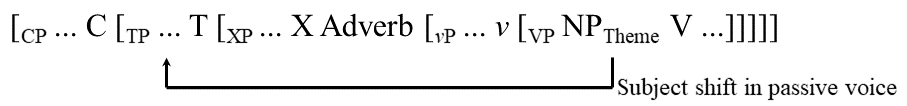

| a. |  |

| b. |  |

That subjects move into the regular subject position has long been a standard claim in generative grammar (especially for passive constructions). This chapter discusses a number of other movement operations that also move elements from the lexical to the functional domain, insofar as this results in a reordering of the constituents in the middle field of the clause: this means that the various forms of wh-movement, which move elements into the clause-initial position, will not be discussed here, but in Section 11.3. Following Ross (1967), the reordering of the middle field is often called scrambling, but there are reasons not to follow this practice, as it incorrectly suggests that we are dealing with a single, uniform phenomenon. We will show that scrambling is actually a pre-theoretical umbrella term for a larger set of movement phenomena with divergent properties. Section 13.2 will discuss nominal argument shift, called NP-preposing in earlier generative literature like Van den Berg (1978) and De Haan (1979); this type of movement affects only nominal arguments and plays an important role in distinguishing between the presupposition and the focus of the clause, i.e. between discourse-old and discourse-new information; cf. the discussion of (9) and (11) above. Section 13.3 will show that negative and contrastive phrases can also be moved to the left; this movement is not restricted to nominal arguments, but can also be applied to constituents of other categories. Section 13.4 concludes by showing that phonologically weak forms like the referential personal pronoun ʼmhim and the locational proform erthere are obligatorily moved to a position close to the regular subject position of the clause. Section 13.1, however, begins by introducing the notion of unmarked word order.