- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section discusses the use of the negative adverb nietnot and the affirmative adverb wel with adjectives. Subsection I first examines what these adverbs modify in predicative constructions such as Jan is niet/wel aardigJan is not/aff nice: do they modify the adjectival complementive or the clause? Subsection II then considers a number of special uses of the negative/affirmative adverb, and Subsection III looks at cases of “quasi”-negation, i.e. cases where negation is implicitly expressed by modifiers like weiniglittle/not very in APs such as weinig behulpzaamnot very helpful. Finally, Subsection IV discusses modifiers that occur only in negative contexts, i.e. modifiers that behave as negative polarity items.

When negation is present in a predicative construction, it is often not clear a priori whether it modifies the complementive or the clause. Consider the near-synonymous sentences in the primeless and primed examples of (287).

| a. | Jan is niet | aardig. | ||

| Jan is not | kind | |||

| 'Jan is not kind.' | ||||

| a'. | Jan is onaardig. | |

| Jan is unkind |

| b. | Ik | vind | Jan niet | aardig. | |||

| I | consider | Jan not | kind | ||||

| 'I do not consider Jan kind.' | |||||||

| b'. | Ik vind | Jan onaardig. | |

| I consider | Jan unkind |

Since the copular verb zijnto be does not express a meaning that can be negated (its presence is mainly motivated by the need to express the tense and agreement features of the clause), semantic considerations do not seem at first glance to help determine whether niet modifies the whole clause or just the AP. This subsection will show that there are reasons to assume that niet modifies the whole clause.

A syntactic reason is that the constituency test shows that the negative adverb and the clause are separate constituents: the (a) and (b)-examples of (288) show that while topicalization of the adjective alone is fully acceptable, pied piping of the negative adverb leads to unacceptability. The (c)-examples show that the negation behaves in this respect like the clause adverbial zekercertainly in examples like Dit boek is zeker leukThis book is certainly amusing. We conclude that the negative adverb expresses sentence negation.

| a. | Aardig | is Jan niet. | |

| kind | is Jan not |

| a'. | * | Niet aardig is Jan. |

| b. | Aardig | vind | ik | Jan niet. | |

| kind | consider | I | Jan not |

| b'. | * | Niet aardig vind ik Jan. |

| c. | Leuk | is dit boek | zeker. | |

| amusing | is this book | certainly |

| c'. | * | Zeker leuk is dit boek. |

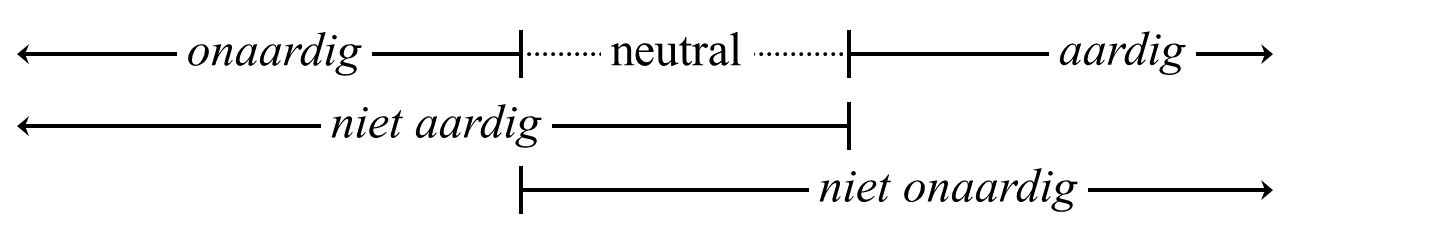

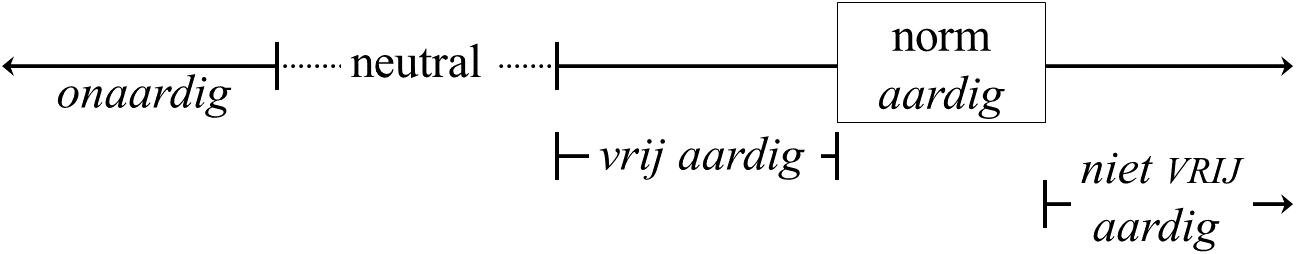

A semantic reason for accepting the conclusion that the negative adverb niet acts as a sentence negation is that this would also account for the fact that the two (a)-examples in (287) are not equivalent: example (289a) is not a contradiction. The felicity of this example is due to the fact that Jan is niet aardig applies to a larger range of the implied scale of kindness than Jan is onaardig: it also includes the neutral zone. The result is that example (289a) locates Jan’s degree of kindness in the neutral zone, i.e. in the overlapping part of niet aardig and niet onaardig. This is illustrated in the graphical semantic representation in (289a).

| a. | Jan is niet aardig, | maar | ook | niet | onaardig. | |

| Jan is not kind, | but | also | not | unkind | ||

| 'Jan is not kind, but he is not unkind either.' | ||||||

| b. | Scale of kindness |

|

The semantic difference between the two (a)-examples in (287) can also be expressed in the logical formulas in (290): in the former, the negation expressed by niet has sentential scope, while the scope of the negation expressed by the prefix -on is restricted to the adjective.

| a. | ¬∃d [aardig (Jan,d)] |

| b. | ∃d [onaardig (Jan,d)] |

Note, however, that the inclusion of the neutral zone is lost if the negative element niet is modified by an absolute modifier like absoluutabsolutely or helemaaltotally. Example (291a) expresses that Jan is quite unfriendly, and example (291b) that Jan is quite friendly.

| a. | Jan is helemaal | niet aardig. | |

| Jan is totally | not kind | ||

| 'Jan is quite unfriendly.' | |||

| b. | Jan is absoluut | niet | onaardig. | |

| Jan is absolutely | not | unkind | ||

| 'Jan is quite friendly.' | ||||

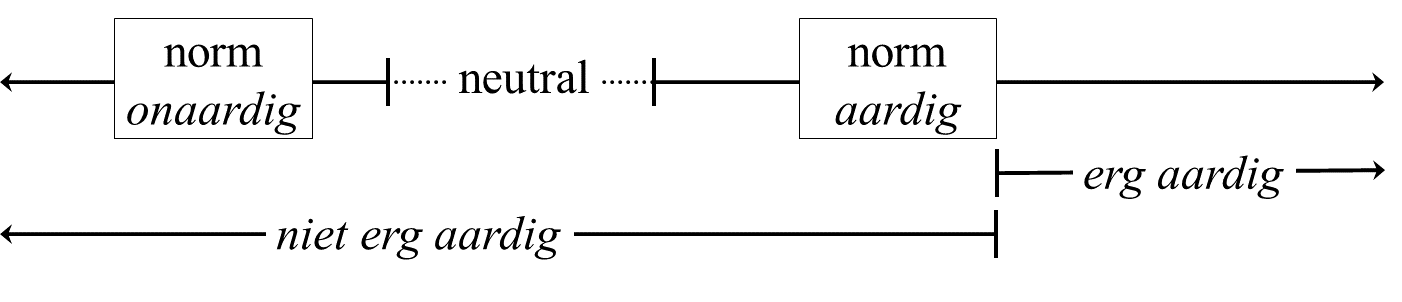

Negation can also be used when an amplifier such as ergvery is present, as in (292a). In (292b) we show the range of the scale implied by niet erg aardig in a graphical representation. Example (292c) provides the semantic representation of niet erg aardig. If the amplifier expresses an extremely high degree, such as afgrijselijkterribly, the result is less felicitous: the amplifiers given in (21) above then yield marked results.

| a. | Jan is niet | erg/?afgrijselijk | aardig. | |

| Jan is not | very/terribly | kind |

| b. | Scale of kindness |

|

| c. | ¬∃d [aardig (Jan, d) & (d > dn)] |

Despite the fact that Jan is niet erg aardig has the meaning in (292c), the intended range of the scale can be further restricted by using accent. If the amplifier is accented, as in (293a), the most salient interpretation is that Jan is kind, but only to a lesser extent; in other words, the degree to which Jan is kind is located somewhere between the neutral zone and the point where the range denoted by erg aardig begins. If the adjective has an accent, as in (293b), the most salient interpretation is that Jan is unkind, i.e. we are dealing with a form of litotes; cf. Subsection IIB.

| a. | Jan is niet | erg aardig. | |

| Jan is not | very kind |

| b. | Jan is niet | erg aardig. | |

| Jan is not | very kind |

This difference in interpretation between (293a) and (293b) is partly semantic in nature, and can be technically explained by assuming that they differ in the scope of negation. In (293a) we are dealing with constituent negation; the scope of negation is limited to the degree modifier ergvery. This means that only the clause d > dn is negated, so that the sentence is assigned the semantic representation ∃d [aardig (Jan, d) & ¬(d > dn)], which is equivalent to ∃d [aardig (Jan, d) & (d ≤ dn)]; this correctly picks out the range between the neutral zone and the range denoted by erg aardig. When we are dealing with sentence negation in (293b), the sentence is assigned the interpretation in (292c). That the most salient interpretation of (293b) is that Jan is unfriendly does not follow from the scope assignment to the negation, but could be explained by appealing to Grice’s (1975) maxim of manner: if the speaker wants to express that Jan is friendly, but not very friendly, he can do so more precisely by using (293a), so that (293b) can be seen as a pragmatically infelicitous means of referring to this range of the scale.

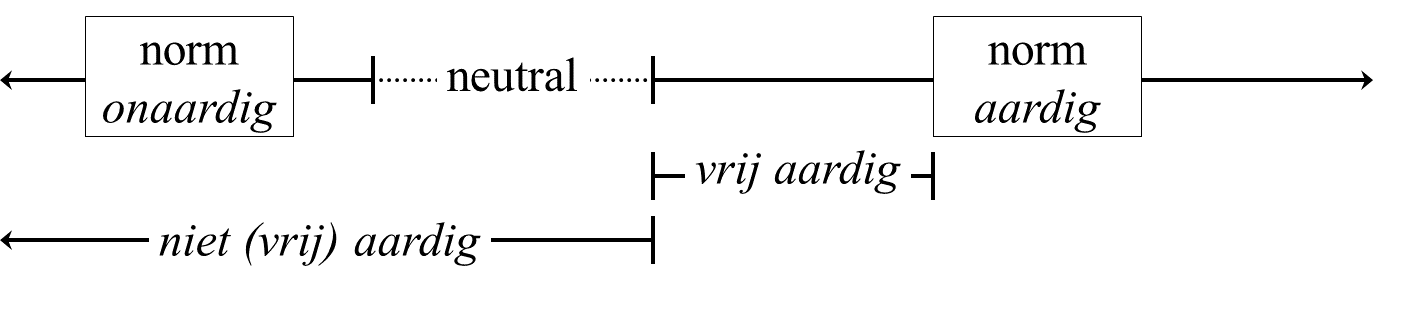

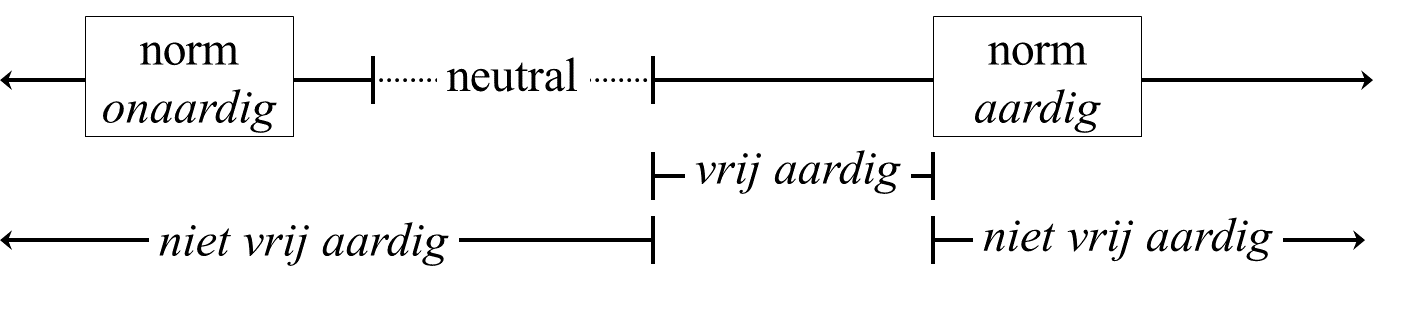

The presence of a downtoner in the scope of sentence negation usually leads to an unacceptable result. One possible explanation for this is that the intended range on the implied scale can be indicated more economically by niet aardignot kind; cf. (294b). However, it seems unlikely that (294b) is the correct graphical representation of the meaning of (294a); the meaning we would expect is given in (294d), which corresponds to the graphical representation in (294c). If (294c) is indeed the correct representation, then sentence (294a) can be excluded by appealing to Grice’s (1975) maxim of quantity, because it produces an uninformative message in the sense that niet vrij aardig refers to two opposite sides of the scale.

| a. | % | Jan is niet | vrij | aardig. |

| Jan is not | rather | kind |

| b. | Incorrect representation of (294a): |

|

| c. | Correct representation of (294a): |

|

| d. | ¬∃d [aardig (Jan,d) & (d < dn)] |

This account of the infelicity of (294a) is consistent with the fact that (294a) becomes more or less acceptable when it is used to deny a presupposition or statement made earlier in the discourse, as in (295), in which case the speaker can propose an alternative on either the left or the right side of the scale.

| Jan is vrij | aardig. | ||

| Jan is rather | kind |

| a. | Nee, | hij | is niet | vrij aardig, | maar | een klootzak. | denial; option 1 | |

| no | he | is not | rather kind | but | a bastard | |||

| 'No, he is not rather nice; he is a bastard.' | ||||||||

| b. | ? | Nee, | hij | is niet | vrij aardig, | maar | ontzettend aardig. | denial; option 2 |

| no | he | is not | rather kind | but | terribly kind | |||

| 'No, he is not rather kind but extremely nice.' | ||||||||

Example (295b) sounds a bit marked, but becomes fully acceptable when an accent is assigned to the degree modifier vrij. In this case, niet expresses constituent negation; the first conjunct of example (296a) is then assigned the semantic representation in (296b), which is semantically equivalent to the representation in (296b'); this option may be preferred to (295b) for pragmatic reasons because it unambiguously places Jan’s kindness at the right end of the scale, as shown in the graphical representation in (295c).

| a. | Nee, | hij is niet | vrij | aardig, | maar | ontzettend | aardig. | |

| no | he is not | rather | kind, | but | terribly | kind |

| b. | ∃d [aardig (Jan,d) & ¬(d < dn)] |

| b'. | ∃d [aardig (Jan,d) & (d ≥ dn)] |

| c. |  |

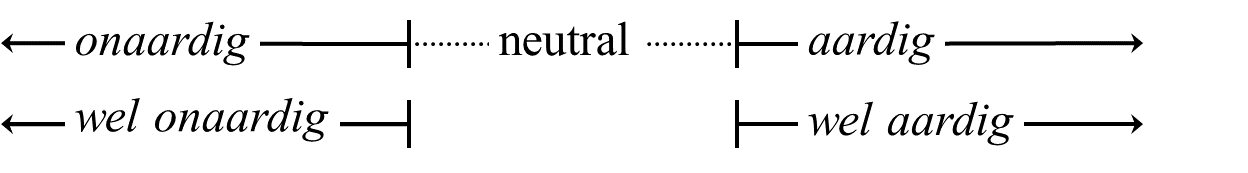

The use of constituent negation in (296) is similar to the use of the (stressed) marker wel, which can thus be seen as the positive counterpart of niet. As shown in (297b), the presence of wel does not affect the part of the scale to which the adjectives onaardigunkind and aardigkind refer. Its main function is to contradict a presupposition or statement made earlier in the discourse; for example, (297a) is only acceptable if the presupposition is that Jan is not kind.

| a. | Jan is wel | aardig. | |

| Jan is aff | kind |

| b. | Scale of kindness |

|

Finally, let us look briefly at the absolute adjectives. In these cases, the negative adverb niet simply indicates that the property denoted by the adjective does not apply. Like approximative and absolute modifiers, the negative adverb itself can be modified. However, while the examples in (279) and (284) have shown that the first two can be modified by both alalready and nogstill, the examples in (298) show that the negation can only be modified by nog. Example (298a) can only be used felicitously if we are emptying bottles, and (298b) if we are filling them. Note in passing that al can be used here as a clause adverbial, meaning “it is already the case that the bottle is not empty”; this is irrelevant in the present context.

| a. | De fles | is nog/*al | niet | leeg. | |

| the bottle | is still/already | not | empty |

| b. | De fles | is nog/*al | niet | vol. | |

| the bottle | is still/already | not | full |

If the adjective is modified by an absolute modifier such as helemaalcompletely, the combination of negation and modifier is more or less equivalent to an approximative: example (299a) is more or less synonymous with De tafel is vrijwel rondThe table is almost round. Approximative modifiers lead to a strange result in the presence of negation, as shown in (299b).

| a. | De tafel | is niet | helemaal | rond. | |

| the table | is not | totally | round |

| b. | % | De tafel | is niet | vrijwel | rond. |

| the table | is not | almost | round |

Example (299b) is marked with a percentage sign because it is acceptable when used to deny a presupposition or statement made earlier in the discourse; cf. (300). This use of negation is similar to its use in the examples in (295) and (296) with a scalar adjective modified by a downtoner.

| a. | De tafel | is vrijwel | rond. | |

| the table | is almost | round |

| b. | De tafel | is niet | vrijwel | rond, | maar | vierkant. | |

| the table | is not | almost | round, | but | square |

| b'. | ? | De tafel | is niet | vrijwel | rond, | maar | helemaal rond. |

| the table | is not | almost | round, | but | totally round |

| b''. | De tafel | is niet | vrijwel | rond, | maar | helemaal rond. | |

| the table | is not | almost | round, | but | totally round |

Subsection I has shown that the scope of the negative adverb niet and the affirmative marker wel can be limited to the degree modifier of an adjective, in which case they are used to deny a presupposition or statement made earlier in the discourse. This subsection discusses other uses of niet and wel with restricted scope.

The affirmative marker wel in “denial” contexts should not be confused with the use of wel as a downtoner. The two cases are easily distinguished because the affirmative marker (but not the downtoner) must be accented and requires a second accent on the following adjective; for clarity, we will orthographically represent the unaccented downtoner wel as wĕl. The downtoner wĕl is special in that it can only be combined with adjectives denoting positively valued properties; cf. van Riemsdijk (2005). This becomes clear by comparing the sentences with the downtoner wĕl and the downtoner vrijrather in the examples in (301). Note that the use of wĕl in the glosses indicates that it cannot be translated into English; the small caps do not indicate accent.

| a. | Hij | is wĕl | aardig/*?onaardig. | |||

| he | is wĕl | kind/unkind | ||||

| 'He is rather kind.' | ||||||

| a'. | Hij | is vrij aardig/onaardig. | ||||

| he | is rather kind/unkind | |||||

| 'He is rather kind/unkind.' | ||||||

| b. | Dit boek | is wĕl | boeiend/*?saai. | |||

| this book | is wĕl | fascinating/boring | ||||

| 'This book is rather fascinating.' | ||||||

| b'. | Dit boek | is vrij boeiend/saai. | ||||

| this book | is rather fascinating/boring | |||||

| 'This book is rather fascinating. | ||||||

| c. | Jan is wĕl | lief/*?stout. | ||

| Jan is wĕl | sweet/naughty | |||

| 'Jan is rather sweet.' | ||||

| c'. | Jan is vrij lief/stout. | |||

| Jan is rather sweet/naughty | ||||

| 'Jan is rather sweet/naughty.' | ||||

Note that negatively valued adjectives are not the same as negative adjectives; ongedwongenrelaxed in (302) is prefixed with the negative affix on-, but it denotes a positively valued property, and modification by wĕl leads to an acceptable result.

| Het sollicitatiegesprek | was wĕl | ongedwongen. | ||

| the interview | was wĕl | casual | ||

| 'The interview took place in a rather relaxed atmosphere.' | ||||

Observe that wĕl can be combined with a negatively valued adjective if it is followed by a degree modifier, which must be given heavy accent. The examples in (303) also show that the degree modifier must be an amplifier and cannot be a downtoner. This would be consistent with the earlier observations, provided that (i) wel is a modifier of the degree modifier, and (ii) amplifiers and downtoners differ in that the former are positively valued and the latter are negatively valued.

| a. | Hij | is wĕl | zeer/*vrij | onaardig. | |

| he | is wĕl | very/rather | unkind |

| b. | Dit boek | is wĕl | erg/*vrij | saai. | |

| this book | is wĕl | very/rather | boring |

| c. | Jan is wĕl | ontzettend/*nogal | stout. | |

| Jan is wĕl | terribly/rather | naughty |

The (a)-examples in (304) show that the sequence wĕl + adjective can be placed in clause-initial position. We conclude that it is a constituent, in contrast to the sequence of stressed affirmative wel + adjective in the (b)-examples; cf. the constituency test.

| a. | Wĕl | aardig | vond | ik | die jongen. | |

| wĕl | kind | consider | I | that boy |

| a'. | * | Aardig vond ik die jongen wĕl. |

| b. | * | Wel | aardig | vond | ik | die jongen. |

| aff | kind | consider | I | that boy |

| b'. | Aardig vond ik die jongen wel. |

Another difference between the downtoner wĕl and the affirmative marker wel is that only the former can be modified by the element best; this is illustrated in (305).

| a. | Hij is best wĕl/*wel aardig. |

| b. | Dit boek is best wĕl/*wel boeiend. |

| c. | Jan is best wĕl/*wel lief. |

Examples like (306a&b) are often referred to as litotes. This trope expresses a property by negating its antonym, and requires the adjective to denote a property that is negatively valued. The examples in (306) are more or less semantically equivalent to those with wĕl in (301), but there is no one-to-one correspondence; niet stout in (306c), for example, sounds decidedly odd in the intended reading, while wĕl lief would be perfectly acceptable. Of course, all of the examples in (306) are acceptable when niet is used to express sentence negation, hence the use of the number sign.

| a. | Hij | is niet | onaardig/#aardig. | |

| he | is not | unfriendly/friendly | ||

| 'He is rather friendly.' | ||||

| b. | Dat boek | is | niet saai/#boeiend. | |

| that book | is | not boring/fascinating | ||

| 'That book is rather fascinating.' | ||||

| c. | # | Jan is niet stout/lief. |

| Jan is not naughty/sweet |

It is often said that in the literary and formal registers litotes is used to obtain a strong amplifying effect; niet onaardig would be used to express something like “extremely friendly”. In colloquial speech, however, such an amplifying effect is only obtained when niet is modified by an absolute modifier like helemaalcompletely or absoluutabsolutely: helemaal/absoluut niet onaardigvery friendly.

Since litotes requires the adjective to denote a negatively valued property, example (307a) can have only one reading, namely the one involving sentence negation. Example (307b), on the other hand, is ambiguous: in the first reading, niet expresses sentence negation, just as in (307a), but in the second reading it modifies the adjective.

| a. | Dat boek | is niet | goed. | |

| that book | is not | good | ||

| 'It is not the case that that book is good.' | ||||

| b. | Dat boek | is niet | slecht. | |

| that book | is not | bad | ||

| 'It is not the case that that book is bad.' | ||||

| 'That book is rather good.' | ||||

The litotes reading is sometimes even strongly preferred. To see this, we should first briefly discuss the adjective aardigkind in its more special meaning “nice”, which we find only with non-human entities. The examples in (308) show that this special reading is possible when the adjective is preceded by wĕl, but excluded when it is preceded by niet, or when sentence negation is expressed by some other element in the clause, such as nietsnothing.

| a. | Dat boek | is | wĕl/*niet | aardig. | cf. Jan is wel/niet aardig ‘Jan is (not) kind.’ | |

| that book | is | wĕl/not | nice | |||

| 'That book is rather nice.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Niets | is | aardig. | cf. Niemand is aardig ‘Nobody is kind’ |

| nothing | is | nice |

The adjective onaardig can also have the special meaning of “not nice” when it is used in a litotes context: thus niet in (309a) cannot be interpreted as sentence negation. That niet must be interpreted as constituent negation is also clear from the fact that negation cannot be realized on any other clausal constituent, because this would imply that we are dealing with sentence negation, so that onaardig should be interpreted with the regular meaning of “unkind”; this can also be seen from the fact that (309b) is only acceptable with a human subject.

| a. | Dat boek | is niet/*wĕl | onaardig. | |

| that book | is not/wĕl | not.nice | ||

| 'That book is rather nice.' | ||||

| b. | Niemand/*Niets | is onaardig. | |

| nobody/nothing | is unkind |

The fact that the downtoners wĕl and niet can also trigger litotes readings in attributive constructions such as (310) also shows that these elements have a restricted scope; the examples in (311) show that the affirmative/negative adverbs wel/niet cannot easily be used internally to the noun phrase.

| a. | een | wĕl | aardig/*onaardig | boek | |

| a | wĕl | nice/not.nice | book |

| a'. | een | niet | onaardig/*aardig | boek | |

| a | not | not.nice/nice | book |

| b. | een | wĕl | interessant/*oninteressant | boek | |

| a | wĕl | interesting/uninteresting | book |

| b'. | een | niet | oninteressant/*?interessant | boek | |

| a | not | uninteresting/interesting | book |

| a. | De radio is niet/wel | kapot. | |

| the radio is not/wel | broken |

| b. | *? | een | niet/wel | kapotte | radio |

| a | not/wel | broken | radio |

Finally, note that there are some isolated cases of “anti-litotes”: the positively valued adjective verkwikkelijkexhilarating in (312), which is used in a metaphorical sense, requires the presence of an element expressing (quasi-)negation or the negative affix -on.

| a. | Die zaak | is *(niet/weinig) | verkwikkelijk. | |

| that affair | is not/little | exhilarating | ||

| 'That is a nasty matter.' | ||||

| b. | een | *(on‑)verkwikkelijke | zaak | |

| a | nasty | busines | ||

| 'an unsavory matter' | ||||

Negation can also be expressed by quasi-negative phrases, in which the negation is in some sense hidden in the meaning of the phrase: weiniglittle in (313a), for example, can be paraphrased with an overt negative as niet veelnot much. Other quasi-negative modifiers are given in (313b&c); in all these cases, the use of the modifier suggests that the property denoted by the adjective does not apply. The dollar sign assigned to (313c), in which niets alternates with the more colloquial form niks, indicates that such examples are old-fashioned and not accepted by all speakers; some other examples are Zij/Dat is niets aardigShe is not at all kind /That is not at all nice, Zij is niets lui; ze werkt hardShe is not lazy, but works hard and Zij is niets bang; ze durft allesShe is not afraid, but dares everything.

| a. | Marie is weinig | behulpzaam. | |

| Marie is little | helpful | ||

| 'Marie is not very helpful.' | |||

| b. | Marie is allesbehalve/allerminst/verre van | behulpzaam. | |

| Marie is all.but/not.the.least.bit/far from | helpful | ||

| 'Marie is anything but/by no means/far from helpful.' | |||

| c. | $ | Marie is niets | behulpzaam. |

| Marie is nothing | helpful | ||

| 'Marie is not helpful at all.' | |||

The modifier weiniglittle is also compatible with a downtoning interpretation. Example (314a) shows that in this interpretation weinig can also be negated, and that the resulting meaning is more or less equivalent to that of the amplifier zeervery. The modifiers in (313b&c) do not allow a downtoning interpretation, and the examples in (314b&c) show that negation of these modifiers is excluded.

| a. | Marie is niet | weinig | behulpzaam. | |

| Marie is not | little | helpful | ||

| 'Marie is quite helpful.' | ||||

| b. | * | Marie is niet allesbehalve/allerminst/verre van behulpzaam. |

| c. | * | Marie is niet niets behulpzaam. |

The modifier weinig can only be used with scalar adjectives that have an absolute antonym; example (315a) is unacceptable, since the antonym of aardig is also gradable; cf. erg onaardigvery unkind. The modifiers in (313b&c) can be used in these contexts.

| a. | ?? | Marie is weinig | aardig. |

| Marie is little | kind |

| b. | Marie is allesbehalve/allerminst/verre van | aardig. | |

| Marie is anything but/very least/far from | kind |

| c. | $ | Marie is niets | aardig. |

| Marie is nothing | kind |

The examples in (316) show that the modifier weinig also differs from the modifiers in (313b) in that it cannot be combined with an absolute adjective; the modifier niets cannot be used in this context either.

| a. | * | De fles is | weinig | leeg. |

| the bottle | little | empty |

| b. | De fles | is allesbehalve/allerminst/verre van | leeg. | |

| the bottle is | anything but/very least/far from | empty |

| c. | * | De fles | is niets | leeg. |

| the bottle | is nothing | empty |

We have little to say about the distribution pattern described above because, to our knowledge, it has not been considered in the literature.

A special case are the negative polarity elements al te and bijster. In colloquial speech, these elements usually occur in the scope of negation; cf. Klein (1997). The construction as a whole is downtoning in nature; some examples are given in (317).

| a. | Dit boek | is *(niet) | bijster | spannend. | |

| this book | is not | bijster | exciting | ||

| 'This book is not very exciting.' | |||||

| b. | Die auto | is *(niet) | al | te groot. | |

| that car | is not | al | too big | ||

| 'That car is moderate in size.' | |||||

The combination al te also occurs without negation, often in more or less fixed expressions like Dit gaat me al te ver\`1Dit is me al te veelThats too much for me’, Hij maakt het al te gortigHe goes too far, and the proverb Al te goed is buurmans gek (lit.: all too good is neighbor’s fool, which may be close to the American saying If you make yourself an ass, don't complain if people ride you). These cases can be considered relics of the older use of al te as a regular amplifier; in more formal registers, al te can still be used without negation. In older stages of Dutch, bijster could also be used as an amplifier in positive contexts, but this use seems to have died out in colloquial speech.

The negative adverb niet and the adjective do not form a constituent, which is clear from the fact that topicalization of the AP strongly favors stranding of the negative adverb niet; cf. (318).

| a. | Bijster spannend is dit boek niet. |

| a'. | ?? | Niet bijster spannend is dit boek. |

| b. | Al te groot is die auto niet. |

| b'. | ?? | Niet al te groot is die auto. |

That niet and the adjective do not form a constituent can also be seen from the fact that the negation can be external to the clause containing bijster/al te, as in the (a)-examples of (319), or expressed on another constituent in the clause, such as nooitnever in the (b)-examples.

| a. | Ik | denk | niet | [dat | dit boek | bijster | spannend | is]. | |

| I | think | not | that | this book | bijster | exciting | is |

| a'. | Ik | geloof | niet | [dat | zijn auto | al | te groot | is]. | |

| I | believe | not | that | his car | al | too big | is |

| b. | Dat soort boeken | zijn | nooit | bijster | spannend. | |

| that sort of books | are | never | bijster | exciting |

| b'. | Dat soort auto’s | zijn | nooit | al | te groot. | |

| that sort of cars | are | never | al | too big |

Furthermore, when the AP is used in attributive position, the negation can be located external to the noun phrase, as in the (a)-examples in (320), expressed by the article, as in the (b)-examples, or placed within the noun phrase, as in the (c)-examples. The noun phrase containing the modifier is enclosed in square brackets.

| a. | Ik denk niet dat dit | [een | bijster | spannend boek] | is. | NP-external negation | |

| I think not that this | a | bijster | exciting book | is | |||

| 'I donʼt think that this book is very exciting.' | |||||||

| a'. | Ik | geloof | niet | dat | hij | een | al | te | grote | auto | heeft. | |

| I | believe | not | that | he | a | al | too | big | car | has | ||

| 'I donʼt think that his car is very big.' | ||||||||||||

| b. | Dit | is | [geen | bijster | spannend | boek]. | negation on article | |

| this | is | no | bijster | exciting | book |

| b'. | Dit | is | [geen | al | te | grote | auto]. | |

| this | is | no | al | too | big | car |

| c. | Dit | is | [een | niet | bijster | spannend | boek]. | NP-internal negation | |

| this | is | a | not | bijster | exciting | book |

| c'. | Dit | is | [een | niet | al | te | grote | auto]. | |

| this | is | a | not | al | too | big | car |

Subsection I has shown that there are also modifiers that cannot occur in the scope of negation. This is especially true for downtoners, as shown in the (a)-examples of (321). However, Subsection I has also shown that the use of negation becomes fully acceptable when the downtoner is used contrastively, as in the (b)-examples, in which case we are dealing with constituent negation. The (c)-examples show that downtoners can also occur in the scope of negation in yes/no questions.

| a. | Dat boek | is (??niet) | vrij saai. | |

| that book | is not | rather boring |

| a'. | Jan is (??niet) | een beetje gek. | |

| Jan is not | a little mad |

| b. | Dat boek | is niet | vrij saai, | maar | verschrikkelijk | saai. | |

| that book | is not | rather boring | but | terribly | boring |

| b'. | Jan is niet | een beetje gek, | maar | volledig | waanzinnig. | |

| Jan is not | a little mad | but | completely | insane |

| c. | Is dat boek | niet | vrij saai? | |

| is that book | not | rather boring | ||

| 'Isnʼt that book rather boring?' | ||||

| c'. | Is Jan niet | een beetje gek? | |

| is Jan not | a little crazy | ||

| 'Isnʼt Jan a little crazy?' | |||

The acceptability of the (b) and (c)-examples suggests that the impossibility of a downtoner in the scope of negation in the declarative (a)-examples is not due to some inherent semantic property of downtoners, but has a pragmatic reason; this was already suggested in our discussion of (294) and (295) in Subsection I.