- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

This section discusses alternations between PPs with various functions and the subject of the clause. Subsection I considers cases in which the PP functions as a complementive; it shows that the possibilities are limited compared to similar cases discussed in Subsection 3.3.2, in which the predicative PP alternates with an accusative phrase. Subsection II continues with alternations involving locational PPs that seem to function as logical subjects of the verb. Subsection III concludes with alternations involving different types of adverbial PPs.

Section 3.3.2, sub IIA, has discussed the alternation between the examples in (508a&b) and suggested that the prefix be- performs a similar function as the adjective volfull in (508c); be- and vol both function as complementives: the only difference is that the prefix must incorporate into the verb to satisfy the requirement that it be supported by another morpheme.

| a. | Jan plakt | de posters | op de muur. | |

| Jan pastes | the posters | on the wall |

| b. | Jan be-plakt | de muur | (met de posters). | |

| Jan be-pastes | the wall | with the posters |

| c. | Jan plakt | de muur | vol (met posters). | |

| Jan pastes | the wall | full with posters |

In (508a) the located object is realized as an accusative object, but the examples in (509) show that the located object can also be realized as the subject of the clause with positional verbs like zittento sit, liggento lie, staanto stand and hangento hang. Since these verbs are unaccusative, we can assume that the subject of the clause functions as the logical subject of the complementive PP, and therefore originates in the same position as the accusative noun phrase in (508a).

| a. | Er | zitten | fouten | in de tekst. | |

| there | sit | errors | in the text | ||

| 'There are errors in the text.' | |||||

| b. | Er | liggen | kleren | op de bank. | |

| there | lie | clothes | on the couch | ||

| 'Clothes are lying on the couch.' | |||||

| c. | Er | staan | veel supporters | op de tribune. | |

| there | stand | many fans | on the stand | ||

| 'Many fans are on the stand.' | |||||

| d. | Er | hangen | slingers | in de kamer. | |

| there | hang | garlands | in the room | ||

| 'There are garlands hanging in the room.' | |||||

This in turn leads to the expectation that the examples in (509) will exhibit similar alternations to example (508a). Given that the positional verbs are unaccusative, we expect that the nominal part of the complementive PP can be realized as a nominative noun phrase, with the concomitant effect that the subject of the clause (i.e. the logical subject of this complementive PP) appears as the nominal part of a met-PP. The examples in (510) show that this expectation is not fulfilled.

| a. | * | De tekst | zit | met fouten. |

| the text | sits | with errors |

| b. | * | De bank | ligt | met kleren. |

| the couch | lies | with clothes |

| c. | * | De tribune | staat | met veel supporters. |

| the stand | stands | with many fans |

| d. | * | De kamer | hangt | met slingers. |

| the room | hangs | with festoons |

However, the expected alternation with the adjectival complementive vol does occur, as shown by (511). The adjective vol adds the semantic aspect that the reference object (location) is affected by the located object; cf. Section 3.3.2, sub IIA1. The extent of the effect can be specified by adding an attributive modifier like heel to the locational noun phrase or a degree modifier such as helemaal to the adjective vol.

| a. | De (hele) tekst | zit | vol | met fouten. | |

| the whole text | sits | full | with errors | ||

| 'The text is full of errors.' | |||||

| b. | De (hele) bank | ligt | vol | met kleren. | |

| the whole couch | lies | full | with clothes | ||

| 'The couch is covered by clothes.' | |||||

| c. | De tribune | staat | (helemaal) | vol | met supporters. | |

| the stand | stands | completely | full | with fans | ||

| 'The stand is full of fans.' | ||||||

| d. | De kamer | hangt (helemaal) | vol | met slingers. | |

| the room | hangs completely | full | with festoons | ||

| 'The room is full of festoons.' | |||||

For completeness’ sake, note that the examples in (511) in turn alternate with the examples in (512). This shows that the location-denoting subjects in (511) can be replaced (at least marginally) by a locative PP, while the subject position is filled by the non-referential pronoun hetit. Alternations of this kind will be discussed in Subsection II.

| a. | ? | Het | zit | vol met fouten | in de tekst. |

| it | sits | full with errors | in the text |

| b. | ?? | Het | ligt | vol met kleren | op de bank. |

| it | lies | full with clothes | on the couch |

| c. | ? | Het | staat | vol | met supporters | op de tribune. |

| it | stands | full | with fans | on the stand |

| d. | ?? | Het | hangt | vol | met slingers in de kamer. |

| it | hangs | full | with festoons in the room |

This subsection discusses the alternation illustrated in (513) and (514), in which the nominal part of a non-predicative locational PP in one clause alternates with the subject of another clause. The starting point of our discussion will be the hypothesis that the subject pronoun het in the primeless examples is an anticipatory pronoun introducing the locational PP, which therefore functions as the logical subject of the construction; cf. Bennis & Wehrmann (1987).

| a. | Het | is | erg warm/gezellig | in de kamer. | |

| it | is | very warm/cozy | in the room |

| a'. | De kamer | is erg warm/gezellig. | |

| the room | is very warm/cozy |

| b. | Het stinkt | in de kamer. | |

| it stinks | in the room |

| b'. | De kamer | stinkt. | |

| the room | stinks |

The subsections below will not cover the copular examples in (513) extensively, since they are discussed in more detail in Section A28.6; instead, we will focus more specifically on the constituent parts of the two alternants in (514), which have a number of peculiar semantic and syntactic properties in addition to those found in (513).

| a. | Het | krioelt | in de tuin | van de mieren. | |

| it | crawls | in the garden | of the ants | ||

| 'The garden is swarming with ants.' | |||||

| b. | De tuin | krioelt | van de mieren. | |

| the garden | swarms | of the ants | ||

| 'The garden is swarming with ants.' | ||||

An important property of the constructions in (513a&b) and (514a) is that they are impersonal, in the sense that the subject pronoun hetit is non-referential. That this is the case can be gathered from the fact that this pronoun cannot be replaced by any referential element (while retaining the intended meaning). This is illustrated in (515) for the demonstrative pronouns ditthis and datthat. The number sign indicates that (515a) is possible if the adjective gezelligcozy is predicated of “having/doing this in the room is cozy”, but cannot be used to say anything about the coziness of the room.

| a. | Dit/Dat | is erg | *warm/#gezellig | in de kamer. | |

| this/that | is very | warm/cozy | in the room |

| b. | * | Dit/Dat stinkt | in de kamer. |

| this/that stinks | in the room |

| c. | * | Dit/Dat | krioelt | in de tuin | van de mieren. |

| this/that | crawls | in the garden | of the ants |

At first glance, the claim that the subject pronoun het is non-referential is problematic for the copular constructions in (513a), because the adjectival complementives warmwarm and gezelligcozy must be predicated of some entity. This problem could perhaps be solved for the adjective warm, in that it takes a quasi-referential subject by positing that it resembles weather verbs such as vriezento freeze, but this seems less likely for adjectives such as gezelligcozy. To solve this problem, it has been proposed that the pronoun het actually functions as an anticipatory pronoun, coindexed with the locational PP, which acts as the logical subject of the adjective. If we extend this proposal to impersonal constructions like (513b) and (514), we arrive at the representations in (516).

| a. | Heti | is [SC ti | erg warm/gezellig] | [in de kamer]i. | |

| it | is | very warm/cozy | in the room |

| b. | Heti | stinkt | [in de kamer]i. | |

| it | stinks | in the room |

| c. | Heti | krioelt | [in de tuin]i | van de mieren. | |

| it | crawls | in the garden | of the ants |

These representations not only resolve the question as to what the adjective/verbs in (513a&b) and (514a) are predicated of, but may also make intuitive sense in light of the fact that the nominal parts of the locational PPs appear as the subject of the alternate constructions in the primed examples in (513) and in (514b). However, let us not jump to conclusions, because the two alternants are not semantically equivalent. This is clear from the examples in (517), taken from Janssen (1976:69): while (517a) unambiguously refers to the space inside the car, (517a') can also be used to refer to the car itself (its engine may need fine-tuning, for example); similarly, while the PP in (517b) can refer to a get-together organized by the Janssen family, the subject in (517b') must refer to the people themselves.

| a. | Het | stinkt | in de auto. | |

| it | stinks | in the car |

| a'. | De auto | stinkt. | |

| the car | stinks |

| b. | Het | was | leuk | bij de Janssens. | |

| it | was | fun | with the Janssens |

| b'. | De Janssens | waren | leuk. | |

| the Janssens | were | fun |

The claim that the locational PPs in (516) function as logical subjects of the clauses not only provides an answer to the question pertaining to the semantic properties discussed in the previous subsection, but is also supported by their syntactic behavior. Let us first rule out two possible alternative analyses. First, the locational PP in de tuin in (514a) cannot be analyzed as a complementive, because (518a) shows that it can be placed after the clause-final verb, and (518b) shows that it need not be left-adjacent to the clause-final verbs but can easily be separated from them by other phrases (here vaak) in the middle field of the clause.

| a. | dat | het | <in de tuin> | krioelt | van de mieren <in de tuin>. | |

| that | it | in the garden | crawls | of the ants |

| b. | dat | het | <in de tuin> | vaak <in de tuin> | krioelt | van de mieren. | |

| that | it | in the garden | often | crawls | of the ants |

The examples in (519) further show that the locational PP differs from unsuspected PP-complementives in that it does not allow R-pronominalization; the PP can only be pronominalized using locational proforms like hierhere and daarthere.

| a. | * | dat | het | eri | vaak [PP ti | in] | krioelt | van de mieren. |

| that | it | there | often | in | crawls | of the ants |

| b. | dat | het | hier/daar | vaak | krioelt | van de mieren. | |

| that | it | here/there | often | crawls | of the ants |

A second possibility would be that the locational PP functions as an adverbial phrase. However, this seems to contradict the fact that it cannot be omitted; example (520a) cannot be interpreted as an impersonal construction, but is only acceptable if the neuter pronoun het is referential, i.e. functions as the pronominalized counterpart of an example such as (520b).

| a. | # | Het | krioelt | van de mieren. |

| it | crawls | of the ants |

| b. | Dat deel van de tuin | krioelt | van de mieren. | |

| that part of the garden | crawls | of the ants |

The conjecture in (516) that the locational PP functions semantically as the logical subject of the clause is compatible with these facts. A possible problem for this conjecture is that the (a)-examples in (521) show that the PP cannot be placed in the regular subject position of the clause; it can only be placed in the clause-initial position if it is topicalized, in which case the non-referential pronoun het must appear in the subject position right-adjacent to the finite verb in second position. However, this is compatible with the proposed analysis if we assume that the regular subject position can only be occupied by a noun phrase and that this is precisely the reason why the anticipatory pronoun is used in this construction.

| a. | * | In de tuin | krioelt | van de mieren. |

| in the garden | crawls | of the ants |

| b. | In de tuin | krioelt | het | van de mieren. | |

| in the garden | crawls | it | of the ants |

In fact, this also explains why het is not needed in the alternants of (521) in (522); since the reference objects in these constructions are syntactically realized as noun phrases, they can of course be placed in regular subject position, so that the insertion of the anticipatory pronoun het is unnecessary (hence blocked).

| a. | De tuin | krioelt | van de mieren. | |

| the garden | crawls | of the ants |

| b. | * | De tuin | krioelt | het van de mieren. |

| the garden | crawls | it of the ants |

The syntactic status of the van-PP is not immediately clear. A first observation is that this PP seems to prefer a position after the clause-final verb, which immediately rules out an analysis according to which the PP functions as a complementive.

| a. | dat | het | in de tuin | <?van de mieren> | krioelt <van de mieren>. | |

| that | it | in the garden | of the ants | crawls |

| b. | dat | de tuin | <?van de mieren> | krioelt <van de mieren>. | |

| that | the garden | of the ants | crawls |

The examples in (524) show that R-pronominalization of the van-PP is possible; this favors an analysis according to which the PP functions as a complement of the verb; however, it is not conclusive because certain adverbial phrases also allow R-pronominalization.

| a. | dat | het | eri | in de tuin [PP ti | van] | krioelt. | |

| that | it | there | in the garden | of | crawls | ||

| 'that it is crawling with them in the garden.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | de tuin | eri | vaak [PP ti | van] | krioelt. | |

| that | the garden | there | often | of | crawls | ||

| 'that the garden is often crawling with them.' | |||||||

Another argument for assuming that the van-PP is a PP-complement and not an adverbial phrase is that omitting this PP leads to a severely degraded result: such an effect is expected for PP-complements, but not for adverbial phrases.

| a. | * | dat | het | in de tuin | krioelt. |

| that | it | in the garden | crawls |

| b. | * | dat | de tuin | krioelt. |

| that | the garden | crawls |

Note that the examples in (525) are semantically incoherent; the verb is taken in its literal sense as a verb denoting undirected motion, while the (logical) subject does not seem to be able to satisfy the selection restrictions imposed by this verb. Adding the van-PP apparently lifts the selection restriction imposed by the verb on its subject. This is consistent with the proposal in Vandeweghe (2020: §3.1.3) that the nominal complement is a kind of demoted subject of the verb comparable with the nominal complement of agentive door-PPs in passives: cf. Mieren krioelen in de tuin ‘Ants are swarming in the garden’. This may even be clearer in the examples in (526).

| a. | dat | de bijen | gonzen | in de tuin. | |

| that | the bees | buzz | in the garden |

| b. | dat | het | gonst | van de bijen | in de tuin. | |

| that | it | buzzes | of the bees | in the garden | ||

| 'that the garden is buzzing with bees.' | ||||||

| c. | dat | de tuin | gonst | van de bijen. | |

| that | the garden | buzzes | of the bees. | ||

| 'that the garden is buzzing with bees.' | |||||

Although plausible at first glance, there are serious problems with proposals of this kind, which will be discussed in the next subjection.

The fact that the (logical) subject need not satisfy the selection restriction that a verb like krioelento crawl imposes on its agentive argument may suggest that the meaning of the constructions in (514) is non-compositional. One way to avoid this conclusion is to assume that the predicative relations in the clause are expressed in a non-canonical way. We will consider one option here, which we will show to be untenable in the light of a wider set of data.

First, consider the examples in (527), which show that the verb krioelen requires its agentive subject to be plural or to be headed by a noun denoting a collection of entities; using a singular noun phrase such as de mierthe ant leads to an unacceptable result.

| a. | De mieren | krioelen | in de tuin. | |

| the ants | crawl | in the garden | ||

| 'The ants are teeming in the garden.' | ||||

| b. | Het ongedierte/*De mier | krioelt | in de tuin. | |

| the vermin/the ant | crawls | in the garden | ||

| 'The vermin are teeming in the garden.' | ||||

The examples in (528) show that the verb krioelen imposes similar restrictions on the nominal part of the van-PP similar to those on the subject in (527); the nominal part of the PP must be plural or refer to a collection of entities. Note in passing that, despite the definiteness of the noun phrase, it does not refer to a contextually determined set of entities, but has a high-degree reading in the sense that it expresses that there are many ants/a lot of vermin; cf. Hoeksema (2009) and Vandeweghe (2020).

| a. | Het | krioelt | in de tuin | van | de mieren/het ongedierte/*de mier. | |

| it | crawls | in the garden | of | the ants/the vermin/the ant |

| b. | De tuin | krioelt | van | de mieren/het ongedierte/*de mier. | |

| the garden | crawls | of | the ants/the vermin/ant |

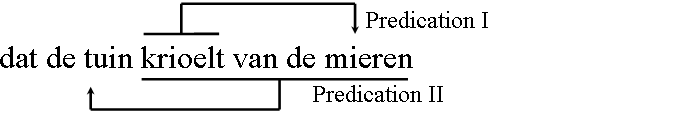

This may suggest that the van-PP functions semantically as the logical subject of the verb. If so, this means that we are dealing with a rather complex set of predication relations, which are schematized in the figures in (529). The two constructions are identical in that the verb is predicated of the nominal part of the van-PP. The complex verbal phrase krioelen van de mieren functions as a predicate which is subsequently predicated of the reference object de tuinthe garden, directly if the latter is realized as the subject of the clause, or via the anticipatory pronoun het if it is realized as a locational PP.

| a. |  | to be rejected |

| b. |  | to be rejected |

There are several possible problems with such analyses. The first is that the predication relation I between the verb and its internal argument is usually not syntactically encoded by the preposition vanof in standard Dutch (although this has been different in earlier stages of the language, as pointed out in Vandeweghe 2020). This does not a priori mean that such an analysis would be untenable, since it is argued in Section N17.4.2.1 that this preposition can establish such a relation in metaphorical N-van-een-N constructions such as een schat van een kata treasure of a cat, in which the noun schat is predicated of the second noun; cf. Die kat is een schatthat cat is a treasure. A second semantic problem is that establishing predication relation I in the structures in (529) should produce a proposition; since propositions are saturated predicates, they cannot normally be predicated of another argument, and this means that we have to make additional stipulations in order to make predication relation II possible. The third and probably most problematic aspect of the analyses in (529) is that it predicts that in constructions of this type the verb is always predicated of the nominal part of the van-PP. However, the examples in (530) show that this need not be the case.

| a. | Het | barst/stikt/sterft | *(van de toeristen) | in de stad. | |

| it | barst/stikt/sterft | of the tourists | in the town | ||

| 'It is swarming with tourists in town.' | |||||

| b. | De stad | barst/stikt/sterft | *(van de toeristen). | |

| the town | barst/stikt/sterft | of the tourists | ||

| 'The town is swarming with tourists.' | ||||

The verbs barstento burst, stikkento suffocate and stervento die are clearly not predicated of the noun phrase de toeristen. Instead, the original meaning of the verbs has bleached and the construction as a whole simply takes on a quantitative aspect of meaning; there is an extremely high number of tourists in town. It may further be noted that the syntactic properties of the verbs barsten, stikken and sterven in the constructions in (530) also differ considerably from their properties in their more regular use. This is shown in (531) and (532) for the verb stikken. Example (531) shows that this verb, being a telic unaccusative verb, forms its perfect tense with the auxiliary zijnto be and cannot be combined with durative adverbial phrases like een uur langfor an hour.

| a. | De jongen | is/*heeft | gestikt. | |

| the boy | is/has | suffocated |

| b. | De jongen | stikte | binnen een minuut/*een uur lang. | |

| the boy | suffocated | within a minute/one hour long |

The constructions in (532), on the other hand, exhibit properties of atelic predicates:

they form their perfect tense with the auxiliary hebbento have and can be combined with durative adverbial phrases such as de hele zomerall summer.

| a. | Het | heeft/*is | in Amsterdam | de hele zomer | gestikt | van de toeristen. | |

| it | has/is | in Amsterdam | the whole summer | gestikt | of the tourists | ||

| 'It has swarmed with tourists in Amsterdam all summer.' | |||||||

| b. | Amsterdam heeft/*is | de hele zomer | gestikt | van de toeristen. | |

| Amsterdam has/is | the whole summer | gestikt | of the tourists | ||

| 'Amsterdam has swarmed with tourists in Amsterdam all summer.' | |||||

To summarize the discussion, we can conclude that the meaning of the constructions under discussion cannot be determined in a compositional way. The verbs in this construction also have the property that their meaning has bleached; they do not denote the same state of affairs as in their more regular use, a semantic change that is also reflected in their syntactic behavior.

An essential aspect of the meaning of the two constructions under discussion seems to be that there is a high concentration of entities at a particular location. It has further been claimed that the two alternants differ in the spread of these entities. Constructions with a nominative subject like (514b) and (530b) are given a holistic interpretation: e.g. (530b) expresses that wherever you go in town, there will be many tourists. Impersonal constructions like (514a) and (530a), on the other hand, have been claimed to be consistent with a partial interpretation: for instance, (530b) may be true if there is a high concentration of tourists in certain limited areas of town.

The nominative/PP alternation under discussion seems to be very productive, and many verb types can enter the construction. Example (513) has already shown that the alternation can occur in copular constructions. The examples in (511) and (512) in Subsection I have further shown that positional verbs with the complementive adjective volfull also enter this alternation; one example is repeated here as (533).

| a. | De tekst | zit | vol | met fouten. | |

| the text | sits | full | with errors |

| b. | Het | zit | vol met fouten | in de tekst. | |

| it | sits | full with errors | in the text | ||

| 'The text has errors everywhere.' | |||||

The examples in (534) provide a number of other possible cases with an adjectival complementive, although these are somewhat harder to judge because they have a more or less idiomatic flavor. The examples in (534) are similar to those in (514) with the verb krioelen and (530) with the verbs barstento burst, stikkento suffocate and stervento die: they contain an obligatory van-PP and express that there is a high concentration of entities denoted by the nominal part of the van-PP at the location denoted by the reference object die krantthat newspaper/de stadthe city.

| a. | ? | Het | staat | bol | van de fouten | in die krant. |

| it | stands | full | of the errors | in that newspaper |

| a'. | Die krant | staat | bol | van de fouten. | |

| that newspaper | stands | full | of the errors | ||

| 'That newspaper bulges with errors.' | |||||

| b. | Het | zag | zwart | van de toeristen | in de stad. | |

| it | saw | black | of the tourists | in the city |

| b'. | De stadnom | zag | zwart | van de toeristen. | |

| the city | saw | black | of the tourists | ||

| 'The city was swarming with tourists.' | |||||

Another set that allows the alternation consists of verbs denoting light and sound emission. Note that the van-PP in (535a') is optional, but this may be due to the fact that schitterento glitter can also be used as a monadic verb: De diamant schitterdeThe diamond sparkled. These constructions again express that there is a high concentration of entities denoted by the nominal part of the van-PP at the location denoted by the reference object de luchtthe sky/de tuinthe garden.

| a. | Het | schitterde | van de sterren | in de lucht. | |

| it | glittered | of the stars | in the sky |

| a'. | De lucht | schitterde | (van de sterren). | |

| the sky | glittered | of the stars | ||

| 'The sky was glittering with stars.' | ||||

| b. | Het gonst | van de bijen | in de tuin. | |

| it buzzes | of the bees | in the garden |

| b'. | De tuin | gonst | van de bijen. | |

| the garden | buzzes | of the bees | ||

| 'The garden is humming with bees.' | ||||

Finally, the examples in (536) provide a number of examples of bodily sensation/function that seem to particularly favor the construction in which the reference object is realized as the subject of the clause.

| a. | Het | kriebelde | op mijn rug | van de vlooien. | |

| it | tickled | on my back | of the fleas |

| a'. | Mijn rug | kriebelde | van de vlooien. | |

| my back | itched | of the fleas |

| b. | ? | Het | duizelde | door zijn hoofd | van de nieuwe ideeën. |

| it | reeled | through his head | of the new ideas |

| b'. | Zijn hoofd | duizelde | van de nieuwe ideeën. | |

| his head | reeled | of the new ideas |

| c. | ?? | Het | droop | langs zijn gezicht | van het zweet. |

| it | dripped | along his face | of the sweat |

| c'. | Zijn gezicht | droop | van het zweet. | |

| his face | dripped | of the sweat |

The discussion of subject-PP alternations discussed in the previous subsections probably only scratches the surface of a much wider range of facts. PPs that alternate with nominative phrases may not only be predicative or function as the logical subject of the clause, but may also function as adverbial phrases of various kinds. The subjects of the adjunct middle constructions in the primed examples in (537) all have a function similar to that of the adverbial phrases in the regular primeless examples; cf. Section 3.2.2.3 for further discussion. Interestingly, the doubly-primed examples show that adjunct middles also have impersonal counterparts.

| a. | Els snijdt | altijd | met dat mes. | instrument | |

| Els cuts | always | with that knife |

| a'. | Dat mes | snijdt | lekker/prettig. | |

| that knife | cuts | nicely/pleasantly | ||

| 'That knife cuts nicely.' | ||||

| a''. | Het | snijdt | lekker/prettig | met dat mes. | |

| it | cuts | nicely/pleasantly | with that knife | ||

| 'That knife cuts nicely.' | |||||

| b. | Peter rijdt | graag | op deze stille wegen. | location | |

| Peter drives | readily | on these quiet roads | |||

| 'Peter likes to drive on these quiet roads.' | |||||

| b'. | Deze stille wegen | rijden | lekker/prettig. | |

| these quiet roads | drive | nicely/pleasantly | ||

| 'It is nice/pleasant to drive on these quiet roads.' | ||||

| b''. | Het | rijdt | lekker/prettig | op deze stille wegen. | |

| it | drives | nicely/pleasantly | on these quiet roads | ||

| 'It is nice/pleasant to drive on these quiet roads.' | |||||

| c. | Jan werkt | het liefst | op rustige middagen. | time | |

| Jan works | preferably | on quiet afternoons | |||

| 'Jan prefers workingon quiet afternoons.' | |||||

| c'. | Rustige middagen | werken | het prettigst. | |

| quiet afternoons | work | the most pleasant | ||

| 'Working on quiet afternoons is pleasantest.' | ||||

| c''. | Het werkt | het prettigst | op rustige middagen. | |

| it works | most.pleasantly | on quiet afternoons | ||

| 'Working on quiet afternoons is pleasantest.' | ||||

But it is not only in adjunct middle constructions that we find adverbial PPs alternating with subjects. For ex 2ample, Section 2.5.1.3 has shown that object-experiencer psych-verbs allow the expression of the cause either by a met-PP or by a nominative noun phrase; this is illustrated again by the examples in (538).

| a. | De clownCauser | amuseerde | de kinderenExp | met zijn grapjesCause. | |

| the clown | amused | the children | with his jokes |

| a'. | Zijn grapjesCause | amuseerden | de kinderenExp. | |

| his jokes | amused | the children |

| b. | JanCauser | overtuigde | de rechterExp | met dat nieuwe bewijsCause. | |

| Jan | convinced | the judge | with that new evidence |

| b'. | Dat nieuwe bewijsCause | overtuigde | de rechterExp. | |

| that new evidence | convinced | the judge |

Adverbial met-PPs exhibit the alternation more generally, as shown in the cases in (539). We will not attempt to characterize the semantic function of the adverbial phrases and their corresponding subjects; cf. Levin (1993: §3) for an attempt to do so for similar English examples.

| a. | Jan bevestigde | de hypothese | met een nieuw experiment. | |

| Jan confirmed | the hypothesis | with a new experiment |

| a'. | Het nieuwe experiment | bevestigde | de hypothese. | |

| the new experiment | confirmed | the hypothesis |

| b. | Het leger | bluste | de bosbrand | met een helikopter. | |

| the army | extinguished | the forest.fire | with a helicopter |

| b'. | De helikopter bluste | de bosbrand. | |

| the helicopter extinguished | the forest.fire |

| c. | Jan vult het tochtgat | met kranten. | |

| Jan fills the draft.hole | with newspapers |

| c'. | De | kranten | vullen | het tochtgat. | |

| the | newspapers | fill | the draft.hole |

| d. | Marie versierde de kamer | met de nieuwe slingers. | |

| Marie decorated the room | with the new festoons |

| d'. | De nieuwe slingers | versierden | de kamer. | |

| the new festoons | decorated | the room |

| e. | Jan bedekte | de inktvlek | met zijn hand. | |

| Jan covered | the inkblot | with his hand |

| e'. | Zijn hand | bedekte | de inktvlek. | |

| his hand | covered | the inkblot |

Levin (1993: §3) provides a number of other cases with adverbial phrases headed by prepositions other than metwith, which are possible in English but lead to unacceptable or at least very unnatural results in Dutch. We will limit ourselves here to a few typical examples. The alternation exemplified in (540), where the adverbial phrase/subject refers to natural forces, is often acceptable.

| a. | Jan droogde | zijn haar | in de wind/zon. | |

| Jan dried | his hair | in the wind/sun |

| b. | De wind/zon | droogde | zijn haar. | |

| the wind/sun | dried | his hair |

Alternations involving adverbial phrases denoting time, containers, prices, raw materials and sources, similar to those given by Levin, yield much worse results. However, we should not jump to conclusions; to our knowledge these kinds of alternations have not yet been thoroughly investigated for Dutch.

| a. | De wereld | zag | het begin van een nieuw tijdperk | in het jaar 1492. | |

| the world | saw | the begin of a new era | in the year 1492 |

| a'. | * | Het jaar 1492 | zag | een nieuw tijdperk. |

| the year 1492 | saw | a new era |

| b. | Jan incorporeert | de kritiek | in de nieuwe versie van zijn proefschrift. | |

| Jan incorporates | the criticism | in the new version of his thesis |

| b'. | * | De nieuwe versie van zijn proefschrift | incorporeert | de kritiek. |

| the new version of his thesis | incorporates | the criticism |

| c. | Jan kocht | een kaartje | voor vijf euro. | |

| Jan bought | a ticket | for five euros |

| c'. | * | Vijf euro | koopt | (je) | een kaartje. |

| five euros | buys | you | a ticket |

| d. | Hij | bakt | heerlijke pannenkoeken | van dat biologische boekweitmeel. | |

| he | bakes | lovely pancakes | from that organic buckwheat.flour |

| d'. | * | Dat biologische boekweitmeel | bakt | heerlijk pannenkoeken. |

| that organic buckwheat.flour | bakes | lovely pancakes |

| e. | De middeninkomens | profiteren | van de belastingverlaging. | |

| the middle.income.earners | profit | from the tax.reduction |

| e'. | * | De belastingverlaging | profiteert | de middeninkomens. |

| the tax.reduction | profits | the middle.income.earners |