- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Example (5a) shows that in embedded clauses verbs are located in what is usually called the clause-final position. Since the use of this term can lead to various misunderstandings, Subsection I first briefly discusses some possible problems with this term. Subsection II then continues with a discussion of verb-first/second (often simply referred to as verb-second), the movement operation that places the finite verb in the first or second position of main clauses. Verb-second is generally found in declarative clauses, in which the finite verb is preceded by the subject or some other phrase; wh-questions such as (5b) are prototypical instantiations of the latter case. Verb-first is found when the first position of the sentence is (phonetically) empty; yes/no questions such as (5c) are prototypical cases of this.

| a. | dat | Jan dat boek | wilfinite | lezeninfinitive. | verb-final | |

| that | Jan that book | wants | read | |||

| 'that Jan wants to read that book.' | ||||||

| b. | Wat | wilfinite | Jan lezeninfinitive? | verb-second | |

| what | wants | Jan read | |||

| 'What does Jan want to read?' | |||||

| c. | Wilfinite | Jan dat boek | lezeninfinitive? | verb-first | |

| wants | Jan that book | read | |||

| 'Does Jan want to read that book?' | |||||

Subsection III concludes the discussion of the placement of the finite verb by considering the verb-first/second rule from a cross-linguistic perspective.

Verbs are usually in clause-final position; Subsection II will show that the only exception is the finite verb, which is moved into first/second position in main clauses. The use of the term clause-final position is inadequate in several ways. First, it suggests that clause-final verbs mark the right boundary of the clause, whereas examples like (6a&b) show that they can in fact be followed by various other constituents, such as PP-complements and embedded clauses; cf. Chapter 12 for more discussion. The term clause-final should therefore be understood more loosely as “in the right periphery of the clause”.

| a. | dat | Jan | al | de hele dag | wacht | op antwoord. | |

| that | Jan | already | the whole day | waits | for answer | ||

| 'that Jan has been waiting for an answer all day.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | Jan aan Peter | vertelt | dat hij naar Groningen gaat. | |

| that | Jan to Peter | tells | that he to Groningen goes | ||

| 'that Jan tells Peter that he is going to Groningen.' | |||||

Second, the use of the term clause-final position may suggest that the clause-final verbs are base-generated as part of a verbal complex in a specific position in the clause. An example of such a verbal complex is given in (7); the finite verb moetmust is in clause-final position in the embedded clause in (7a), but is moved to verb-second position in the main clause in (7b).

| a. | dat | hij | dat boek | morgen | moet hebben | gelezen. | |

| that | he | that book | tomorrow | must have | read | ||

| 'that he must have read that book by tomorrow.' | |||||||

| b. | Hij | moet | dat boek | morgen tmoet | hebben | gelezen. | |

| he | must | that book | tomorrow | have | read | ||

| 'He must have read that book by tomorrow.' | |||||||

However, the insertion of a base-generated verbal complex is not what is generally assumed in generative grammar: there are reasons to assume that the verbs that enter the verbal complex are all base-generated as heads of independent verbal projections in a hierarchical structure. This structure is insightfully shown in the English translation of (7a) in (8). The structural representation in (8) formally expresses the intuition that the perfect auxiliary have selects a phrase headed by a participle and that the modal verb must selects a phrase headed by an infinitive; cf. Section 5.2 and Chapter 6 for detailed discussions.

| that he must [have [read that book tomorrow]]. |

The fact that the verbs in the Dutch examples in (7) tend to cluster in clause-final position must therefore be epiphenomenal (which is clearly the case for the adjacent sequence of verbs in English examples such as (8), which can easily be interrupted by adverbs), or the result of some movement operation. The latter is the option traditionally chosen for Germanic OV languages like Dutch and German, and this has motivated operations such as Evers’ (1975) verb-raising transformation. We confine ourselves to noting this issue here, and refer the reader to Chapter 7 for a detailed discussion of verb clustering.

It should be emphasized that the term clause-final position is a technical term referring to a more deeply embedded position in the phrase structure, i.e. a position at least internal to XP in Figure (2). Despite the fact that the finite verbs in the two primeless examples in (9) are clause-final in a pre-theoretical sense, we will maintain that the finite verb is in clause-final position in the technical sense only in (9a); in (9b) the finite verb is in second position (T or C). The difference between the two positions becomes immediately apparent when we add additional constituents, like the adverbial phrases graaggladly and in het parkin the park in the primed examples.

| a. | dat | Jan wandelde. | |||||

| that | Jan walked | ||||||

| 'that Jan was walking.' | |||||||

| a'. | dat | Jan graag | in het park | wandelde. | |||

| that | Jan gladly | in the park | walked | ||||

| 'that Jan liked to walk in the park.' | |||||||

| b. | Jan wandelde. | ||||

| Jan walked | |||||

| 'Jan was walking.' | |||||

| b'. | Jan wandelde | graag | in het park. | ||

| Jan walked | gladly | in the park | |||

| 'Jan liked to walk in the park.' | |||||

For the primed examples in (9) we will maintain that the adverbial phrases occupy the middle field not only in (9a') but also in (9b'). However, this is difficult to prove in the latter case, since the clause-final verb position is empty. In some cases, however, the presence of the clause-final position can be established indirectly with the help of some other element in the clause. This can be illustrated in a simple way by separable particle verbs such as doorgevento pass on in (10). The primeless examples clearly show that nominal and clausal direct objects differ in that the former occupy a position in the middle field, whereas the latter occupy a position in the postverbal field of the clause. But the same can be inferred indirectly from the position of the particle door in the corresponding main clauses in the primed examples, since verbal particles are normally placed left-adjacent to the clause-final verbs (if present).

| a. | dat | Jan | <het zout> | doorgaf <*het zout>. | |

| that | Jan | the salt | prt.-gave | ||

| 'that Jan passed the salt.' | |||||

| a'. | Jan gaf | <het zout> | door <*het zout> | |

| Jan gave | the salt | prt. | ||

| 'Jan passed the salt.' | ||||

| b. | dat | Jan | <*dat Peter ziek was> | doorgaf <dat Peter ziek was>. | |

| that | Jan | that Peter ill was | prt.-gave | ||

| 'that Jan passed the message on that Peter was ill.' | |||||

| b'. | Jan gaf | <*dat Peter ziek was> | door <dat Peter ziek was>. | |

| Jan gave | that Peter ill was | prt. | ||

| 'Jan passed the message on that Peter was ill.' | ||||

There are a number of elements that are usually left-adjacent to the clause-final verbs, including complementives and stranded prepositions; cf. Chapter 13 for discussion and examples.

In main clauses, finite verbs are usually in the first or second position. We will adopt the generally accepted assumption from generative grammar that all verbs are base-generated in some lower position in the clause (because they are all the head of a projection of their own), and that finite verbs are special in that they are moved into the verb-first/second (C or T) position in main clauses. The special status of finite verbs is usually explained by assuming that the verb-first/second position contains temporal (T) and/or illocutionary (C) features associated with the finite verb.

The contrast between embedded and main clauses with respect to the position of finite verbs is illustrated again in (11), in which the verbs are italicized; note that in (11a) the declarative complementizer datthat is obligatory, and that in (11b) gisterenyesterday is in the clause-initial position as a result of topicalization.

| a. | Marie zegt | [dat | Jan gisteren | dat boek | heeft | gekocht]. | declarative | |

| Marie says | that | Jan yesterday | that book | has | bought | |||

| 'Marie says that Jan bought that book yesterday.' | ||||||||

| b. | Gistereni | heeft | Jan ti | dat boek | gekocht. | |

| yesterday | has | Jan | that book | bought | ||

| 'Jan bought that book yesterday.' | ||||||

In the wh-questions in (12) we find essentially the same difference in verb placement. Note, however, that the initial position of the embedded question is filled by a wh-phrase, whereas this position must remain empty in the declarative clause in (11a), and that the interrogative complementizer ofif is optional and usually not present in writing/formal speech.

| a. | Marie vroeg | [wati (of) | Jan gisteren ti | heeft | gekocht]. | wh-question | |

| Marie asked | what if | Jan yesterday | has | bought | |||

| 'Marie asked what Jan bought yesterday.' | |||||||

| b. | Wati | heeft | Jan gisteren ti | gekocht? | |

| what | has | Jan yesterday | bought | ||

| 'What did Jan buy yesterday?' | |||||

In the polar yes/no questions in (13) the clause-initial position of the interrogative clauses remains phonetically empty, although we have seen in Section 9.3, sub I, that there is reason to assume that it is syntactically filled by a question operator. As a result, the complementizer of must be overtly expressed to mark the embedded clause as interrogative, and the finite verb ends up in the first position of the main clause.

| a. | Marie vraagt | [of | Jan gisteren | dat boek | heeft | gekocht]. | yes/no question | |

| Marie asks | if | Jan yesterday | that book | has | bought | |||

| 'Marie asks whether Jan bought that book yesterday.' | ||||||||

| b. | Heeft | Jan gisteren | dat boek | gekocht? | |

| has | Jan yesterday | that book | bought | ||

| 'Did Jan buy that book yesterday?' | |||||

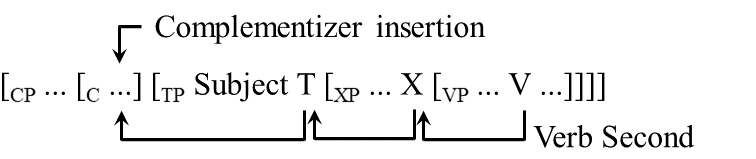

It is traditionally assumed that the verbs in first and second position are actually in the same position, so that verb-first and verb-second can be considered to follow from the same rule. The restriction of verb-first/second to main clauses suggests that complementizer insertion and verb-second are in complementary distribution; cf. Paardekooper’s (1961). Den Besten (1983) concluded from this that complementizers in embedded clauses and finite verbs in main clauses both occur in the C-position, as indicated in (14a). The representation in (14b) shows that verb-second constructions like (11b) and (12b) are derived by an additional movement of some phrase into the specifier of CP, i.e. the position immediately preceding the C-position. In yes/no questions such as (13b) the finite verb ends up in the first position because there is no phonetically realized material in the main-clause initial position (although it may be filled by a phonetically empty question operator).

| a. |  |

| b. |  |

The traditional analysis of verb-second in (14) holds that in main clauses the finite verb always targets the C-position, and that any phrase preceding the verb in second position must have been placed there by wh-movement. However, Section 9.3 has shown that subject-initial sentences and other verb-second sentences differ in whether the finite verb can be preceded by an unstressed element: example (15a) is acceptable regardless of whether the subject pronoun is stressed or not, while the (b) and (c)-examples in (15) show that other clause-initial (topicalized) phrases must be stressed.

| a. | Zij/Ze | moeten | mij | helpen. | subject pronoun in initial position | |

| they/they | must | me | help | |||

| 'They must help me.' | ||||||

| b. | Hen/*Ze | moet | ik | helpen. | object pronoun in initial position | |

| them/them | must | I | help | |||

| 'I must help her.' | ||||||

| c. | Op hen/*ze | wil | ik | niet | wachten. | PP-complement in initial position | |

| for them/them | want | I | not | wait | |||

| 'I do not want to wait for her.' | |||||||

| c'. | Daarop/*Erop | wil | ik | niet | wachten. | pronominal PP in initial position | |

| for that/for it | want | I | not | wait | |||

| 'I do not want to wait for that.' | |||||||

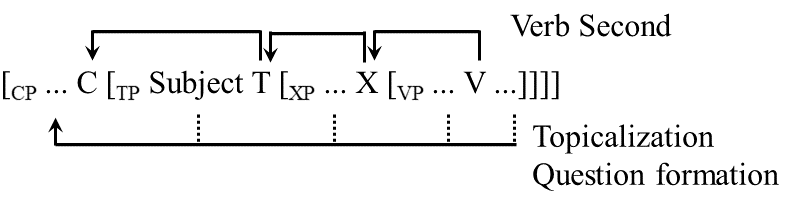

The (b) and (c)-examples in (15) strongly suggest that topicalization of unaccented or phonetically reduced phrases is not possible, which in turn suggests that at least the weak subject pronoun zethey in (15a) cannot be in the specifier position of the CP, but must be in the regular subject position, i.e. the specifier of the TP. Since there is no a priori reason to assume that strong subject pronouns such as henthey or non-pronominal subjects must be treated differently, the null hypothesis seems to be that what we postulate for phonetically reduced subject pronouns holds for all subjects. Thus we arrive at the hypothesis that subject-initial sentences normally have the structure in (16); cf. Travis (1984) and Zwart (1993/1997).

|

The Travis/Zwart hypothesis, which assigns different structures to subject-initial sentences (TPs) and other verb-second constructions (CPs), may also explain another fact. The subject pronoun jeyou triggers different types of agreement depending on its position relative to the finite verb, as shown in (17). This would follow if we assume that the morphological realization of subject-verb agreement depends on the position of the finite verb in the clause, T or C; cf. Zwart (1997) and Postma (2011). In (17a) the finite verb occupies the T-position and second-person singular agreement is morphologically expressed by -t, whereas in (17b) it occupies the C-position and second-person singular agreement is expressed by -Ø.

| a. | [TP | Je | krijgt [XP | morgen | een cadeautje tV]]. | |

| [TP | you | get2p.sg | tomorrow | a present | ||

| 'You will get a present tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | [CP | Morgen | krijg-Ø [TP | je tV [XP tmorgen | een cadeautje tV]]]. | |

| [CP | tomorrow | get2p.sg | you | a present | ||

| 'You will get a present tomorrow.' | ||||||

If we accept the proposals in (14b) and (16), the term verb-second no longer uniquely refers to movement of the verb into the C-position, and in the more recent formal-linguistic literature this term is therefore often replaced by the more precise terms V-to-T and V-to-C. Here, we will retain the term verb-second as a convenient descriptive term.

Since the Travis/Zwart hypothesis is highly theory-internal, we will not discuss it in detail, but we would like to point out that it has given rise to several hotly debated issues. First, the Travis/Zwart hypothesis crucially assumes that the T-position in Dutch is to the left of the lexical projections of the verbs, as shown in (16), and thus deviates from the more traditional claim, motivated by the OV-nature of Dutch, that the T-position is to the right of these projections, as in [CP .. C [TP .. [VP ..V] T]]. Second, the Travis/Zwart hypothesis is incompatible with the traditional claim that the clause-final placement of the finite verb in embedded clauses follows from the fact that verb-second targets the C-position, since the finite verb could now in principle also be moved into the T-position of embedded clauses, as in (18b).

| a. | [C | dat] | Jan [T — ] | dat boek | gisteren | heeft | gekocht. | |

| [C | that | Jan | that book | yesterday | has | bought | ||

| 'that Jan bought that book yesterday.' | ||||||||

| b. | * | [C dat] Jan [T heeft ] dat boek gisteren theeft gekocht. |

Third, the Travis/Zwart hypothesis makes it impossible to account for the obligatory nature of verb-second in main clauses by simply stating that the C-position must be lexically filled; instead, we must assume that the highest head position in the extended projection of the verb is lexically filled: T in subject-initial main clauses, and C in other verb-second constructions as well as embedded clauses. This proposal may also partly answer the question why the T-position cannot be filled in embedded clauses, i.e. why examples such as (18b) are unacceptable in Dutch. A functional explanation could be that in Dutch a complementizer or a finite verb is placed in the first/second position to signal the beginning of a new clause; cf. Zwart (2001) and Broekhuis (2008) for a formalization of this intuition, and Zwart (2011) for a more detailed review of theoretical approaches to verb-second.

The rules that determine the placement of finite verbs in Dutch are relatively simple: finite verbs occur in the verb-second position in main clauses, but occupy the so-called clause-final position in embedded clauses (where they cluster with the non-finite verbs, if present). The examples in (19) illustrate this again.

| a. | Jan leest | dit boek niet. | |||||

| Jan reads | this book not | ||||||

| 'Jan does not read this book.' | |||||||

| a'. | dat | Jan dit boek | niet | leest. | |||

| that | Jan this book | not | reads | ||||

| 'that Jan does not read this book.' | |||||||

| b. | Jan heeft | dit boek | niet | gelezen. | ||||||

| Jan has | this book | not | read | |||||||

| 'Jan has not read this book.' | ||||||||||

| b'. | dat | Jan dit boek | niet | gelezen | heeft. | |||||

| that | Jan this book | not | read | has | ||||||

| 'that Jan has not read this book.' | ||||||||||

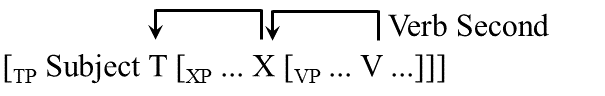

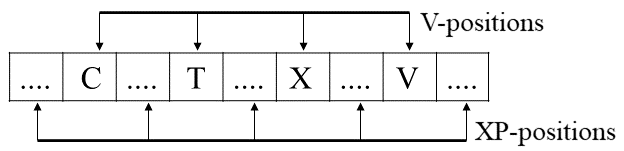

This can be described by claiming that the finite verb is base-generated in the clause-final V-position in the universal template in (20), repeated from Section 9.1, but is moved into the second position by verb-second in main clauses. Subsection II further suggested that the categorial status of the verb-second position depends on the sentence-initial phrase: it can be identified as T in subject-initial sentences and as C in all other cases.

|

The universal template in (20) can be taken to imply that the situation might very well have been different, in the sense that the Dutch rules are simply a more or less random selection from a wider range of verb-movement possibilities. This is supported by cross-linguistic evidence. Consider the Icelandic examples in (21), taken from Jónsson (1996:9-10). If we compare the primeless and primed examples, we see that at first glance the finite verbs seem to occupy the same position in main and embedded clauses, and since the finite verb is adjacent to the subject we can assume that the position in question is T. The fact that the main verbs in the (a) and (b)-examples occupy different positions with respect to the adverb ekkinot shows that non-finite verbs occupy a lower position in the structure than finite verbs (X or V depending on the position of the direct object). This suggests that in Icelandic finite verbs are moved from the V-position into the T-position (or into the C-position in constructions with verb-subject inversion, not discussed here).

| a. | Jón las | ekki | þessa bók. | |||||

| Jón read | not | this book | ||||||

| 'Jón did not read this book.' | ||||||||

| a'. | að | Jón las | ekki | þessa bók. | ||||

| that | Jón read | not | this book | |||||

| 'that Jón did not read this book.' | ||||||||

| b. | Jón hefur | ekki | lesið | þessa bók. | ||||||

| Jón has | not | read | this book | |||||||

| 'Jón has not read this book.' | ||||||||||

| b'. | að | Jón hefur | ekki | lesið | þessa bók. | |||||

| that | Jón has | not | read | this book | ||||||

| 'that Jón has not read this book.' | ||||||||||

The difference between Dutch and Icelandic shows that these languages differ in whether there is an asymmetry in verb movement to T between root and embedded clauses; the examples in (19) and (21) show that this asymmetry is present in Dutch, which is therefore classified as an asymmetric verb movement language, but not in Icelandic, which is classified as a symmetric verb movement language. The examples in (22) show that English is also a symmetric verb movement language, but exhibits an asymmetry between main and non-main verbs; the symmetric verb movement behavior in root and embedded clauses is evident from the similarity in word order between the primeless and primed examples; the asymmetry between main and non-main verbs is evident from the fact that finite non-main verbs must precede the frequency adverb often, whereas finite main verbs must follow it.

| a. | John often read this book. |

| a'. | that John often read this book. |

| b. | John has often read the book. |

| b'. | that John has often read this book. |

There are also symmetric verb-movement languages that have no verb-second at all: for example, Japanese always has the finite verb in clause-final position, as shown in the examples in (23), taken from Tallerman (2015).

| a. | Hanakoga | susi-o | tukurimasita. | |

| Hanako-nom | sushi-acc | made | ||

| 'Hanako made sushi.' | ||||

| b. | Taroo-ga | [Hanako-ga | oisii | susi-o | tukutta | to] | itta. | |

| Taroo-nom | Hanako-nom | delicious | sushi-acc | made | comp | said | ||

| 'Taro said that Hanako made delicious sushi.' | ||||||||

From a cross-linguistic perspective on verb movement, Dutch has at least the following distinctive properties: (i) it has V-to-T/C, (ii) V-to-T/C holds for finite main and non-main verbs alike, and (iii) V-to-T/C applies only in root clauses. Table (24) summarizes the differences with the other languages mentioned.

| V-to-T/C | main/non-main verb | root/non-root clause | |

| Icelandic | + | symmetric | symmetric |

| Dutch | + | symmetric | asymmetric |

| English | + | asymmetric | symmetric |

| Japanese | — | symmetric | symmetric |

The properties in Table (24) place Dutch in the same class as German. However, Dutch and German differ in one important respect: while German sometimes allows verb-second in embedded object clauses without complementizers, Dutch does not; cf. Haider (2010:46-8). The examples in (25) show that German has two forms of embedded declarative clauses: one with the complementizer dassthat and a clause-final finite verb, and one without a complementizer and a verb in second position. Embedded verb-second occurs especially when the finite verb is a subjunctive; note that in (25b) the adverbial phrase nie zuvornever before is placed in clause-initial position and that the verb precedes the subject, so we can conclude that the finite verb occupies the C-position.

| a. | Peter sagte | [dass | er | nie | zuvor | so einen guten Artikel | gelesen | hätte]. | |

| Peter said | that | he | never | before | such a good article | read | had | ||

| 'Peter said that he had never read such a good article before.' | |||||||||

| b. | Peter sagte | [nie zuvor | hätte | er | so einen guten Artikel | gelesen]. | |

| Peter said | never before | had | he | such a good article | read |

The Dutch counterparts of (25) in (26) show that Dutch does not allow verb-second in embedded clauses. The number sign in (26b) indicates that this example is acceptable if the bracketed clause within square brackets is construed as a direct quote (which requires a clear intonation break before the quotation), but this is not the intended reading here. For completeness, note that embedded verb-second constructions are possible in some non-standard varieties of Dutch; cf. Barbiers et al. (2008: §1.3.1.8).

| a. | Peter zei | [dat | hij | nooit eerder | zo’n goed artikel | gelezen | had]. | |

| Peter said | that | he | never before | such a good article | read | had | ||

| 'Peter said that he had never read such a good article before.' | ||||||||

| b. | # | Peter zei | [nooit eerder | had | hij | zo’n goed artikel | gelezen]. |

| Peter said | never before | had | he | such a good article | read |

This section has shown that certain placements of finite verbs that are theoretically possible and actually occur in other languages are excluded in Dutch. The universal template in (20) can be used to provide a descriptively adequate account of the variation in verb placement in the languages discussed in this section by setting the parameters in Table (24). The actual setting is, of course, a language-specific matter; cf. Broekhuis (2011/2023) for further discussion.