- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Dutch allows for a wide variety of word orders in the middle field of the clause. This subsection discusses the relative order of nominal arguments and modal clause adverbials such as waarschijnlijkprobably. All nominal arguments of the main verb can either precede or follow such adverbials, which is illustrated in (33) with a direct object and a subject. We will see that the word-order variation in (33) is not free, but restricted by information-structural considerations, namely the division between presupposition (discourse-old information) and focus (discourse-new information); cf. Van den Berg (1978), De Haan (1979) and Verhagen (1979/1986).

| a. | Marie | wil | <het boek> | waarschijnlijk <het boek> | kopen. | |

| Marie | wants | the book | probably | buy | ||

| 'Marie probably wants to buy the book.' | ||||||

| b. | Morgen | zal | <die vrouw> | waarschijnlijk <die vrouw > | het boek kopen. | |

| tomorrow | will | that woman | probably | the book buy | ||

| 'Tomorrow that woman will probably buy the book.' | ||||||

There are various analyses of the word-order variations in (33); cf. the reviews in the introduction to Corver & Van Riemsdijk (1994) and (2007/2008: §2.1). For example, it has been claimed that the orders in (33a) are not related to movement of the object. One version of this claim can be found in Neeleman (1994a/1994b), where it is claimed that both structures in (33) can be base-generated, as shown by the structures in (34). We will call this the flexible base-generation approach.

| a. | Marie wil [V' waarschijnlijk [V' dat boek kopen]] |

| b. | Marie wil [V' dat boek [V' waarschijnlijk kopen]] |

A slightly more complex version of this claim is found in Vanden Wyngaerd (1988/1989), where it is claimed that the object obligatorily moves into a designated accusative case position, which is indicated in (35) as the specifier of XP. The word-order variation is accounted for by assuming that the clause adverbial can be generated in different base positions: it can be adjoined either to VP or to XP. We will call this the flexible modification approach; cf. Booij (1974) for an earlier proposal with similar properties.

| a. | Marie wil [XP waarschijnlijk [XP het boeki X [VP ti kopen]]] |

| b. | Marie wil [XP het boeki X [VP waarschijnlijk [VP ti kopen]]] |

This section will opt for a flexible movement analysis: we assume that the nominal arguments are base-generated to the right of the clause adverbial within the lexical domain of the clause, but that under certain conditions, which will be specified later, they shift to a position in the functional domain to the left of the modal clause adverbial, as illustrated for the object in the simplified structure in (36).

| a. | Marie wil [VP waarschijnlijk [VP dat boek kopen]] |

| b. | Marie wil [XP dat boeki X [VP waarschijnlijk [VP ti kopen]]] |

The details of the flexible movement approach are developed in Subsection I, which will also show that there are empirical reasons for preferring the flexible movement approach to the two alternative approaches. Subsection II discusses a concomitant effect of nominal argument shift on the intonation pattern of the clause: while non-shifted arguments can be assigned sentence accent, shifted arguments cannot. We will argue that this can also be used as an argument in favor of the flexible movement approach. Having thus firmly established that nominal argument shift is derived by movement, Subsection III will argue that this movement is of the same type as that found in e.g. passive constructions: we are dealing with A-movement.

- I. A flexible movement approach to nominal argument shift

- II. Nominal argument shift and the location of sentence accent

- III. Nominal argument shift is A-movement

This subsection provides a number of empirical arguments for a flexible movement approach to nominal argument shift. Subsection A begins by arguing that object shift involves leftward movement: objects move to a landing site located higher than (i.e. to the left of) the base position of the subject; subjects move to the regular subject position right-adjacent to the complementizer/finite verb in the second position of the clause (i.e. the specifier of TP). Subsection B goes on to show that the movement is sensitive to the information structure of the clause: nominal argument shift can usually apply only when the argument is part of the presupposition (discourse-old information) of the clause. Finally, Subsection C discusses a word-order constraint on the output structures of nominal argument shift. Some of the issues addressed in the following subsections are discussed in more detail in Sections N21.1.2 and N21.1.4, but are briefly repeated here for convenience.

This subsection reviews two classic empirical arguments for a movement analysis to nominal argument shift: wat-voor split and VP-topicalization.

The standard argument for a movement analysis of nominal argument shift is that placement of the nominal argument in front of the modal clause adverbial leads to a freezing effect. We illustrate this in (37) with the so-called wat-voor split. Example (37a) first shows that the string wat voor een boek can be fronted as a whole and should therefore be considered a phrase; the full string functions as a direct object. This in turn strongly suggests that the split in (37b) is derived by wh-extraction of wat from the wat-voor phrase. The acceptability contrast between the two (b)-examples shows that the wat-voor split requires the remnant of the direct object to follow the modal adverb waarschijnlijkprobably; cf. Den Besten (1985). If the word-order difference between the (b)-examples is indeed due to leftward movement of the direct object across the clause adverbial, the unacceptability of (37b') can be accounted for by appealing to freezing: the wh-element wat has been extracted from a moved phrase.

| a. | [NP Wat voor een boek]i | zal | Marie waarschijnlijk ti | kopen? | |

| what for a book | will | Marie probably | buy | ||

| 'What kind of book will Marie probably buy?' | |||||

| b. | Wati | zal | Marie waarschijnlijk [NP ti | voor een boek] | kopen? | |

| what | will | Marie probably | for a book | buy |

| b'. | * | Watj | zal | Marie [NP tj | voor een boek]i | waarschijnlijk ti | kopen? |

| what | will | Marie | for a book | probably | buy |

Den Besten (1985) also claims that the wat-voor split is categorically excluded for subjects of transitive verbs, but Reuland (1985), Broekhuis (1987/1992), De Hoop (1992), Neeleman (1994a), and De Hoop & Kosmeijer (1995) have shown that the split is possible when the subject is not in the regular subject position, but occupies a position further to the right; this can be seen from the fact that the split is possible when the regular subject position in (38b) is occupied by the expletive er, but not when the expletive is absent.

| a. | [NP | Wat voor vogels]i | zullen | (er) ti | je voedertafel | bezoeken? | |

| [NP | what for birds | will | there | your bird.table | visit | ||

| 'What kind of birds will visit your bird table?' | |||||||

| b. | Wati | zullen | ??(er) [NP ti | voor vogels] | je voedertafel | bezoeken? | |

| what | will | there | for birds | your bird.table | visit | ||

| 'What kind of birds will visit your bird table?' | |||||||

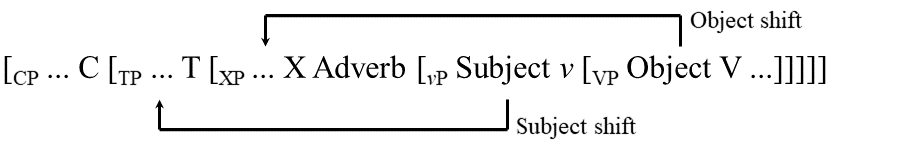

This suggests that the subject is moved into the regular subject position from a more deeply embedded (more rightward) base position in the clause. This is consistent with the fact that in current generative grammar it is generally assumed that this base position is the specifier of the light verb v, as indicated in (39); cf. the introduction to this chapter.

| [CP ... C [TP ... T [XP ... X [vP Subject v [VP ... V ... ]]]]] |

Example (33b) has already shown that subject shift can cross the modal clause adverbial waarschijnlijkprobably, which was an important reason to assume that such adverbials demarcate the left boundary of the lexical domain of the clause (which is now taken to be the vP). If so, the movement of the object, as in (33a), also targets a position in the functional domain of the clause. A currently more or less standard assumption is that both types of nominal argument shift are motivated by case assignment. This means that the subject and the object (optionally) move into the specifier of some functional head responsible for structural case assignment: T for nominative case and some lower functional head X for accusative case. The many different proposals concerning the nature of X need not concern us here; we will therefore not elaborate on what X is, and refer the reader to Broekhuis (2008: §3.1) for an overview (including proposals that dispense with the category X altogether).

|

For completeness, we conclude this discussion of the wat-voor split by noting that there may be reason to doubt that freezing should really be held responsible for the unacceptability of example (37b') and example (38b) without the expletive er. A viable alternative account might appeal to the fact that interrogative wat-voor phrases are non-D-linked, and that this may simply block object/subject shift; that nominal argument shift of wat-voor phrases may indeed be impossible is strongly suggested by the sharp contrast in acceptability between the two multiple wh-questions in (41).

| a. | Wie zal | waarschijnlijk | wat voor boek | kopen? | |

| who will | probably | what for book | buy | ||

| 'Who will probably buy what kind of book?' | |||||

| b. | * | Wie zal | wat voor boek | waarschijnlijk | kopen? |

| who will | what for book | probably | buy |

Nevertheless, the absence of a freezing effect in (37b) and (38b) with the expletive er still supports the claim that remnants of wat-voor phrases should be located within the lexical domain of the clause, and thus also the claim that the subject and object are base-generated within vP.

Another classic argument for a movement analysis of nominal argument shift concerns VP-topicalization; cf. De Haan (1979) and Webelhuth & Den Besten (1987/1990). Since nominal argument shift is optional, the analysis in (40) correctly predicts that VP-topicalization can either pied-pipe or strand the direct object.

| a. | Marie wil | <het boek> | waarschijnlijk [VP <het boek> | kopen]. | |

| Marie wants | the book | probably | buy | ||

| 'Marie probably wants to buy the book.' | |||||

| b. | [VP | Het boek | kopen] | wil | Marie waarschijnlijk tVP. | |

| [VP | the book | buy | wants | Marie probably |

| b'. | [VP ti | Kopen] | wil | Marie het boeki | waarschijnlijk tVP. | |

| [VP ti | buy | wants | Marie the book | probably |

The analysis in (40) also accounts for the fact, illustrated in (43), that VP-topicalization cannot strand the object in a position following the clause adverbial, because there is simply no landing site for the object there; note that Section 13.3.2 will return to the fact that (43) is acceptable if the object is contrastively accented.

| * | [VP ti | Kopen] | wil | Marie waarschijnlijk | het boeki tVP. | |

| * | [VP ti | buy | wants | Marie probably | the book |

Note that the acceptability contrast between of (42b') and (43) is a problem for the flexible modification approach in (35), repeated here as (44), according to which the object is obligatorily moved into its case position. This analysis overgenerates by allowing us to derive both (42b') and (43) by VP-topicalization: the former can be derived from (44b) and the latter from (44a).

| a. | Marie wil [XP waarschijnlijk [XP het boeki X [VP ti kopen]]] |

| b. | Marie wil [XP het boeki X [VP waarschijnlijk [VP ti kopen]]] |

The contrast in acceptability between (42b') and (43) also poses a serious problem for the flexible base-generation approach in (45) because it is usually claimed that topicalization is only possible with maximal projections; if so, (42b') and (43) are both predicted to be ungrammatical, because they can only be derived by moving the verbal head in isolation. If we were to allow topicalization of the verbal head, there would still be a problem, because this would incorrectly predict both (42b') and (43) to be acceptable, since there would then be no obvious reason to assume that (43) cannot be derived from (45a) by V-topicalization.

| a. | Marie wil [V' waarschijnlijk [V' het boek kopen]] |

| b. | Marie wil [V' het boek [V' waarschijnlijk kopen]] |

The flexible movement approach in (40) can also easily account for the fact that it is not possible to pied-pipe clause adverbials by pointing to the fact that these are not included in the lexical projection of the verb (i.e. vP); cf. Section 8.4.

| a. | * | [Waarschijnlijk het boek kopen] wil Marie. |

| b. | * | [Het boek waarschijnlijk kopen] wil Marie. |

| c. | * | [Waarschijnlijk kopen] wil Marie het boek. |

The flexible modification approach cannot account for the unacceptability of the examples in (46). The reason is that this approach can only account for the acceptability of the examples in (42b&b') by assuming that VP-topicalization moves XP in (44a) and VP in (44v). Consequently, it should be possible to derive example (46a) from (44a) by topicalizing the higher segment of XP, example (46b) from (44b) by topicalizing XP, and (46c) from (44b) by topicalizing the higher segment of VP. Even if we assume that only the lower segments of XP and VP can be topicalized, the unacceptability of example (46b) would still remain a problem, since it can be derived by topicalizing the XP in (44b). Similar problems arise for the flexible base-generation approach, since it should be possible to derive examples (46a) and (46b) from (45a) and (45b), respectively, by topicalizing the higher segments of V', and (46c) from (45b) by topicalizing the lower segment of V'. Even if we assume that only the lower segments of V' can be topicalized, an option that should be allowed in order to derive example (42b) from (45a), the unacceptability of (46c) would remain a problem. We conclude that the flexible modification and flexible base-generation approaches can account for the unacceptability of the examples in (46) only by appealing to ad hoc restrictions on what can and cannot be topicalized; the VP-topicalization data thus favors the flexible movement approach.

Example (33a), repeated here as (47a), shows that the direct object het boekthe book can either precede or follow the modal clause adverbial waarschijnlijkprobably. Although this suggests that object shift is optional, the examples in (47b&c) show that this is not always true: indefinite direct objects must follow, while definite object pronouns must precede the clause adverbial.

| a. | dat | Marie | <het boek> | waarschijnlijk <het boek> | koopt. | |

| that | Marie | the book | probably | buys | ||

| 'that Marie will probably buy the book.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Marie | <*een boek> | waarschijnlijk <een boek> | koopt. | |

| that | Marie | a book | probably | buys | ||

| 'that Marie will probably buy a book.' | ||||||

| c. | dat | Marie | <het> | waarschijnlijk <*het > | koopt. | |

| that | Marie | it | probably | buys | ||

| 'that Marie will probably buy it.' | ||||||

In fact, the two orders in (47a) are not always equally felicitous. The order in which the direct object precedes the clause adverbial is normally used when the referent of the noun phrase is already part of the discourse domain; cf. Verhagen (1986). This is illustrated by the question-answer pair in (48): because the direct object is already introduced as a discourse topic in question (48a), it precedes the adverb in answer (48b). Note that we are abstracting from the fact that there is an even better way of answering question (48a), viz. by substituting the pronoun hetit for the noun phrase het boekthe book.

| a. | Wat | doet | Marie | met het boek? | question | |

| what | does | Marie | with the book | |||

| 'What is Marie doing with the book?' | ||||||

| b. | Ik denk | dat | ze | <het boek> | waarschijnlijk <#het boek> | koopt. | answer | |

| I think | that | she | the book | probably | buys | |||

| 'I think that she will probably buy the book.' | ||||||||

When asked out of the blue, a question such as (49a) requires an answer in which the direct object provides new information and follows the clause adverbial; the order in which the object precedes the adverb is only possible if the referent of the direct object is already part of the domain of discourse, e.g. when the speaker and the addressee discuss Jan’s wish list, which includes a specific book title.

| a. | Wat | koopt | Marie voor Jan? | question | |

| what | buys | Marie for Jan | |||

| 'What will Marie buy for Jan?' | |||||

| b. | Ik denk | dat | ze | <#het boek> | waarschijnlijk <het boek> | koopt. | answer | |

| I think | that | she | the book | probably | buys | |||

| 'I think that she will probably buy the book.' | ||||||||

The above discussion shows that direct objects preceding a modal clause adverbial refer to discourse-old information, whereas direct objects following the clause adverbial refer to discourse-new information. Since definite pronouns and indefinite noun phrases typically refer to discourse-old and discourse-new information, respectively, their placement relative to the clause adverbial in the examples in (47) follows naturally. Another fact that follows naturally from this information-structural restriction on argument placement is that epithets always precede clause adverbials; they always refer to an active discourse topic.

| dat | Jan <de etter> | waarschijnlijk <*de etter> | haat. | ||

| that | Jan the son.of.a.bitch | probably | hates | ||

| 'that Jan probably hates the son of a bitch.' | |||||

Note, however, that the notion of discourse-new information should be taken quite broadly, in that it is not confined to the referential properties of the noun phrase. An example illustrating this, inspired by Verhagen (1986:106ff), is given in (51). Although the referent of the noun phrase de verkeerdethe wrong person is clearly identifiable for both participants, the neutral continuation of the discourse is as given in (51b), with the noun phrase following the clause adverbial: this is due to the fact that Peter is now introduced in the new guise of “the wrong person to give the relevant information to”. Note in passing that example (51b') is possible with a contrastive accent on the noun phrase, in which case this utterance is likely to be followed by another one revealing the identity of the person who should have been informed.

| a. | Ik | heb | het | aan Peter | verteld. | speaker A | |

| I | have | it | to Peter | told | |||

| 'I have told it to Peter.' | |||||||

| b. | Dan | heb | je | waarschijnlijk | de verkeerde | ingelicht. | speaker B | |

| then | have | you | probably | the wrong.one | prt.-informed | |||

| 'Then you have probably informed the wrong person.' | ||||||||

| b'. | * | Dan | heb | je | de verkeerde | waarschijnlijk | ingelicht. | speaker B |

| then | have | you | the wrong.one | probably | prt.-informed |

The examples in (52) show that subjects behave in essentially the same way as the objects in (47); cf. Van den Berg (1978). However, this is somewhat obscured by a complicating factor, viz. that indefinite subjects may precede the clause adverbial if they are interpreted as specific (i.e. known to the speaker but not to the addressee) or if they are part of a generic sentence. We will ignore this here, but return to the distinction between specific and non-specific indefinite subjects in Subsection C.

| a. | dat | <die vrouw> | waarschijnlijk <die vrouw> | het boek koopt. | |

| that | that woman | probably | the book buys | ||

| 'that that woman will probably buy the book.' | |||||

| b. | dat | <#een vrouw> | waarschijnlijk <een vrouw> | het boek koopt. | |

| that | a woman | probably | the book buys | ||

| 'that a woman will probably buy the book.' | |||||

| c. | dat | <ze> | waarschijnlijk <*ze> | het boek koopt. | |

| that | she | probably | the book buys | ||

| 'that she will probably buy the book.' | |||||

The discussion above has shown that the relative order of the object/subject and modal clause adverbials is sensitive to the information-structural function of the object/subject. This seems to favor an approach in which the restriction on word order is formulated in terms of properties of the subject/object, and thereby again disfavors the flexible modification approach in (35), according to which the word-order variation is due to alternative placements of the clause adverb. The flexible modification approach also runs into a contradiction concerning the placement of clause adverbials relative to the regular subject position, the specifier of TP. Consider the expletive constructions in (53). If we adopt the standard assumption that the expletive er occupies the regular subject position, which is corroborated by the fact that it is right-adjacent to the complementizer dat, the acceptability contrast in (53) shows that clause adverbials must follow the subject position.

| a. | dat | er | waarschijnlijk | een man | op straat | loopt. | |

| that | there | probably | a man | in.the.street | walks | ||

| 'that there is probably a man walking in the street.' | |||||||

| b. | * | dat waarschijnlijk er een man op straat loopt |

The conclusion that clause adverbials cannot be placed in front of the regular subject position makes it very unlikely that the order variation in (52a) can be explained by assuming variable base positions for the modal adverb, as suggested by the line of reasoning found in Vanden Wyngaerd (1989): if (in the absence of the expletive er) the subject is obligatorily moved to the regular subject position in order to obtain nominative case, the order in an example such as dat waarschijnlijk die man op straat looptthat that man is probably walking in the street would imply that the clause adverbial can precede the regular subject position, contrary to what is shown by (53b). The resulting contradiction does not arise if we assume subject shift; cf. Broekhuis (2009b) for further discussion.

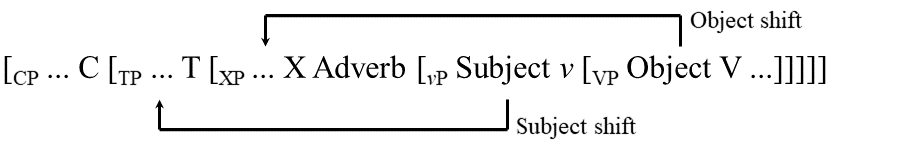

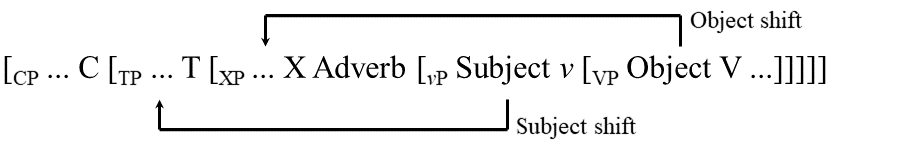

If we adopt the claim that nominal argument shift targets a position in the functional domain of the clause where the subject/object can be assigned case or agreement features, we can summarize the results of Subsection B as in (54); cf. Broekhuis (2008: §3), De Hoop (1992: §3), and Delfitto & Corver (1998) for different implementations of the same idea.

| Information-structural constraints on nominal argument shift: | ||

| a. | Nominal arguments expressing discourse-new information stay within the lexical domain of the clause. |

| b. | Nominal arguments expressing discourse-old information move into their case position in the functional domain of the clause. |

Now consider again the derivation proposed in (40), repeated here as (55). This derivation, together with the two constraints in (54), predicts that an object expressing discourse-old information will cross a subject expressing discourse-new information.

|

Although this prediction is more or less correct for languages such as German, it is clearly wrong for standard Dutch, since in the middle field of the clause the subject usually precedes the direct object, as stated in the word-order preservation constraint in (56): cf. De Haan (1979: §4), Haegeman (1993a/1995), Williams (2003) and Müller (2000/2001) for extensive discussions of this constraint.

| Word-order preservation constraint on nominal argument shift in standard Dutch: nominal argument shift constraint does not affect the unmarked order of nominal arguments (agent > goal/experiencer > theme). |

The word-order preservation constraint can only operate in full force if the constraints in (54) can sometimes be violated. The following subsections will show that this is indeed what we find; cf. Broekhuis (2008/2009a) for a more detailed analysis.

Example (57a) again shows that definite subjects and objects can be placed to the right of modal clause adverbials such as waarschijnlijk if they are part of the focus of the clause, i.e. the discourse-new information. The examples in (57b&c) show that both the subject and the object can move to the left of the clause adverbial if they are part of the presupposition of the clause. The effect of the word-order preservation constraint on nominal argument shift in (56) is illustrated by (57d); a presuppositional object cannot shift across the subject if the latter belongs to the focus of the clause and thus has to follow the modal adverb. This means that example (57a) is information-structurally ambiguous in that the direct object can either be part of the focus or part of the presupposition of the clause; in the second case, the discourse-old object would occupy a position within the lexical domain of the clause, in violation of constraint (54b).

| a. | dat | waarschijnlijk | de jongens | dit boek | gelezen | hebben. | |

| that | probably | the boys | this book | read | have | ||

| 'that the boys have probably read this book.' | |||||||

| b. | dat de jongens waarschijnlijk dit boek gelezen hebben. |

| c. | dat de jongens dit boek waarschijnlijk gelezen hebben. |

| d. | * | dat dit boek waarschijnlijk de jongens gelezen hebben. |

The results are different if we replace the direct object dit boekthis book with the pronoun hetit. Example (58a) first shows that the object pronoun differs from non-pronominal objects in that it cannot remain within the lexical domain of the clause if the subject is part of the focus of the clause. Example (58b) shows that it behaves like non-pronominal objects in that it cannot cross the subject, but (58c) shows that it differs from non-pronominal objects in that it can push the subject up into the regular subject position of the clause. This means that the subject in (58c) can be interpreted not only as part of the presupposition of the clause, but also as referring to discourse-new information, in violation of constraint (54a); the latter is clear from the fact that this example can be used as an answer to the question Wie hebben het boek gelezen?Who have read the book?.

| a. | * | dat | waarschijnlijk | de jongens | het | gelezen | hebben. |

| that | probably | the boys | it | read | have |

| b. | * | dat | het | waarschijnlijk | de jongens | gelezen | hebben. |

| that | it | probably | the boys | read | have |

| c. | dat | de jongens | het | waarschijnlijk | gelezen | hebben. | |

| that | the boys | it | probably | read | have | ||

| 'that the boys probably have read it.' | |||||||

Note in passing that examples such as (58a) become perfectly acceptable when the subject is given contrastive stress; this shows that in such cases the subject can block object shift of the pronominal object in violation of the information-structural constraint (54b); we refer the reader to Section 13.3 for a discussion of the placement of contrastively focused phrases.

| dat | waarschijnlijk | de jongens | het | gelezen | hebben. | ||

| that | probably | the boys | it | read | have | ||

| 'that the boys have probably read it.' | |||||||

We find a similar pattern with indefinite subjects. However, the situation is complicated by the fact that the subject can receive a non-specific interpretation (i.e. unknown to the speaker and the hearer) or a specific interpretation (i.e. known to the speaker but unknown to the hearer). For example, the actual interpretation of the indefinite subject twee jongens in (60) depends on its placement relative to the modal clause adverbial: if it follows waarschijnlijkprobably, it is preferably interpreted as non-specific, whereas it must be interpreted as specific if it precedes it (cf. also Section N21.1.2, sub I).

| a. | dat | waarschijnlijk | twee jongens | dit boek | gelezen | hebben. | |

| that | probably | two boys | this book | read | have | ||

| Ambiguous: 'that two (of the) boys have probably read this book.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | twee jongens | waarschijnlijk | dit boek | gelezen | hebben. | |

| that | two of the boys | probably | this book | read | have | ||

| Specific only: 'that two of the boys have probably read this book.' | |||||||

The result changes again if we replace the direct object het boekthe book with the pronoun hetit. Placing the indefinite subject after the clause adverbial, as in (61a), again requires that the subject be assigned a contrastive accent; in the case of a neutral intonation pattern, the pronoun pushes the subject up into the regular subject position right-adjacent to the complementizer, as in (61b). This is again in violation of the information-structural constraints in (54): that the subject in (61b) can provide discourse-new information violates (54a), and that the contrastively accented subject in (61a) blocks object shift of the pronoun violates (54b).

| a. | dat | waarschijnlijk | twee jongens/*jongens | het | gelezen | hebben. | |

| that | probably | two boys | it | read | have | ||

| 'that two boys (not girls) have probably read it.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | twee jongens | het | waarschijnlijk | gelezen | hebben. | |

| that | two boys | it | probably | read | have | ||

| Ambiguous: 'that two (of the) boys have probably read it.' | |||||||

The data above shows that referential object pronouns such as hetit can force subjects expressing discourse-new information into the regular subject position adjacent to the complementizer, in violation of the information-structural constraint (54a). Object shift of the referential pronoun can also be blocked, in violation of the information-structural constraint (54b), if the subject is assigned contrastive focus accent. This shows that the constraints in (54) are not absolute, but can be overridden to satisfy the “stronger” word-order preservation constraint on nominal argument shift in (56). This suffices to show that there is a complex set of factors that interact (in the technical sense of optimality theory developed in Prince & Smolensky 2004) in determining the surface position of the nominal arguments of the clause.

The discussion of the interaction of object and subject shift in Subsection 1 has shown that the information-structural constraints in (54) can be overridden by the word-order preservation constraint on nominal argument shift in (56). The same can be demonstrated by the interaction of indirect object and direct object shift. Since this is also discussed in detail in Section N21.1.4, sub IE, we will confine ourselves here to a brief review of the relevant data. The examples in (62) show more or less the same as the examples in (57); although both the direct and the indirect object can shift across the modal adverb, the direct object cannot cross the indirect object in its base position.

| a. | dat | hij waarschijnlijk | zijn moeder | het boek | heeft | gegeven. | |

| that | he probably | his mother | the book | has | given | ||

| 'that he has probably given his mother the book.' | |||||||

| b. | dat hij zijn moeder waarschijnlijk het boek heeft gegeven. |

| c. | dat hij zijn moeder het boek waarschijnlijk heeft gegeven. |

| d. | * | dat hij het boek waarschijnlijk zijn moeder heeft gegeven. |

The examples in (63) show more or less the same as the examples in (58). Example (63a) first shows that the object pronoun differs from non-pronominal direct objects in that it cannot remain within the lexical domain of the clause when the indirect object is part of the focus of the clause. Example (63b) shows that the object pronoun behaves like non-pronominal direct objects in that it cannot cross the indirect object, while (63c) shows that it differs from them in that it is able to push the indirect object up into the functional domain of the clause. Note that, as in the cases discussed in Subsection 1, the judgments only hold under a non-contrastive intonation pattern; the orders in (63a&b) improve if the indirect object is assigned a contrastive focus accent.

| a. | * | dat hij waarschijnlijk zijn moeder het heeft gegeven. |

| b. | * | dat hij het waarschijnlijk zijn moeder heeft gegeven. |

| c. | ? | dat | hij zijn moeder | het | waarschijnlijk | heeft | gegeven. |

| that | he his mother | it | probably | has | given | ||

| 'that he probably has given it to his mother.' | |||||||

The fact that example (63c) is still somewhat marked may be somewhat surprising at first sight; this may be related to the fact that the pronoun can precede the indirect object in (63c), dat hij het zijn moeder waarschijnlijk heeft gegeven, but we postpone discussion of this issue to Section 13.4. The markedness of (63c) may also be related to the fact that it competes with the periphrastic construction dat hij het waarschijnlijk aan zijn moeder heeft gegeventhat he has probably given it to his mother, which does not run afoul of the information-structural constraint (54a). The markedness of (64a) with a contrastively stressed indirect object blocking object shift of the pronoun hetit may have a similar reason: the periphrastic construction in (64b) does not induce a violation of the information-structural constraint (54b) that we see in (64a).

| a. | ? | dat | hij | waarschijnlijk | zijn moeder | het | heeft | gegeven. |

| that | he | probably | his mother | it | has | given |

| b. | dat | hij | het | waarschijnlijk | aan zijn moeder | heeft | gegeven. | |

| that | he | it | probably | to his mother | has | given | ||

| 'that he probably has given it to his mother.' | ||||||||

For completeness’ sake, note that Dutch is quite different from German, which allows the direct object to cross the indirect object. This is illustrated in (65) by examples taken from Vikner (1994).

| a. | dass | Peter wirklich | Maria | das Buch | gezeigt | hat. | German | |

| that | Peter really | Maria | the book | shown | has |

| b. | dass Peter Maria wirklich tIO das Buch gezeigt hat. |

| c. | dass Peter Maria das Buch wirklich tIO tDO gezeigt hat. |

| d. | dass Peter das Buch wirklich Maria tDO gezeigt hat. |

The previous two subsections have argued that the word-order preservation constraint on nominal argument shift in (56) cannot be violated in Dutch, unlike in German. This subsection discusses a putative counterexample to this claim. The problem is illustrated by example (66), which shows that passive ditransitive and dyadic unaccusative constructions do not obey the word-order preservation constraint. Assuming that the orders in the primeless examples (goal/experiencer > theme) are unmarked, we would expect the primed examples to be unacceptable under a neutral, non-contrastive intonation pattern, but both orders seem perfectly acceptable, although some speakers may prefer a periphrastic indirect object to the nominal indirect object in (66a'), an option not available for nom-dat verbs.

| a. | dat | Elsdat | de boekennom | worden | aangeboden. | passive | |

| that | Els | the books | are | prt.-offered | |||

| 'that the books will be offered to Els.' | |||||||

| a'. | dat de boekennom Elsdat worden aangeboden. |

| b. | dat | de meisjesdat | de tochtnom | bevallen | is. | nom-dat verb | |

| that | the girls | the trip | pleased | is | |||

| 'that the trip has pleased the girls.' | |||||||

| b'. | dat de tochtnom de meisjesdat bevallen is. |

| c. | dat | de gastendat | de soepnom | gesmaakt | heeft. | nom-dat verb | |

| that | the guests | the soup | tasted | has | |||

| 'that the soup has pleased the guests.' | |||||||

| c'. | dat de soepnom de gastendat gesmaakt heeft. |

However, the primed examples seem to impose specific constraints on the placement of modal clause adverbials such as waarschijnlijkprobably under a neutral intonation pattern: the number signs are used to indicate that the indirect objects may follow the adverbial only if they are assigned a contrastive accent. Since Section 13.3 will show that contrastively accented phrases are at least sometimes external to the lexical domain of the clause, it seems reasonable to conclude that the word-order preservation constraint is valid only insofar as it prohibits nominal argument shift across another nominal argument that remains within the lexical domain of the clause; for independent evidence in support of this claim, see the discussion of the interaction between nominal argument shift and wh-movement in Section N21.1.4, sub V.

| a. | dat | de boeken | <Els> | waarschijnlijk <#Els> | worden | aangeboden. | |

| that | the books | Els | probably | are | prt.-offered | ||

| 'that the books will probably be offered to Els.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | de tocht | <de meisjes> | waarschijnlijk <#de meisjes> | bevallen | is. | |

| that | the trip | the girls | probably | pleased | is | ||

| 'that the trip has probably pleased the girls.' | |||||||

| c. | dat | de soep | <de gasten> | waarschijnlijk <#de gasten> | gesmaakt | heeft. | |

| that | the soup | the guests | probably | tasted | has | ||

| 'that the soup has probably pleased the guests.' | |||||||

If we can indeed draw the conclusion that the word-order preservation constraint in (56) should be reinterpreted as a prohibition of nominal argument shift across another nominal argument that remains within the lexical domain of the clause, the “reversed” orders can be derived as shown for examples (67b) in the derivation sketched in (68). First, (68a) gives the base order, which can actually be found when both arguments are part of the new-information focus of the clause. Second, (68b) is the order derived by shifting both nominal arguments to the left, and again this order can actually be found when the nominal arguments are both part of the presupposition of the clause; note that this structure satisfies the word-order preservation constraint because the order between the experiencer and the theme is the same as in (68a). Finally, the “reversed” order of (67b) is derived as in in (68c) by moving the theme argument de tocht into the regular subject position; this shift crosses the indirect experiencer object de meisjes, but this is allowed since it is no longer in the lexical domain.

| a. | dat [waarschijnlijk [VP de meisjes de tocht bevallen is]]. |

| b. | dat [XP de meisjesi de tochtj X [waarschijnlijk [VP ti tj bevallen is]]]. |

| c. | dat [TP de tochtj T [XP de meisjesi het t'j X [waarschijnlijk [VP ti tj bevallen is]]]]. |

The discussion in this subsection has shown that nominal argument shift is regulated by the information-structural constraints in (54) in interaction with the word-order preservation constraint on nominal argument shift in (56). According to (54), nominal arguments move into their case/agreement position in the functional domain of the clause when they express discourse-old information, but remain in the lexical domain of the clause when they express discourse-new information, provided that this does not violate the word-order preservation constraint. We have also seen that constraint (56) is only valid insofar as it prohibits nominal argument shift across another nominal argument that remains within the lexical domain; the theme argument of a passive ditransitive or a dyadic unaccusative construction may cross the goal argument on its way to the regular subject position, provided that the latter has undergone object shift.

Some of the issues discussed in this subsection are also discussed in Chapter N21. Section N21.1.4 focuses on object shift and addresses issues more specifically related to special types of nominal objects: noun phrases with a generic or partitive reading, indefinite noun phrases with a specific or non-specific reading, quantified noun phrases, etc. This section also discusses the placement of nominal objects relative to a wider range of adverbial phrases, including manner adverbials, negation, and temporal/locational adverbials preceding the modal adverbials. Section N21.1.2 deals more specifically with issues related to subject shift in expletive erthere constructions.

The introduction to this section has mentioned that there are three approaches to nominal argument shift. We have adopted the flexible movement approach, according to which the nominal argument is can be moved from the lexical domain of the clause to a particular case or agreement position in the functional domain of the clause if certain information-structural conditions are met; and we have shown that there are empirical reasons for preferring this approach to the flexible base-generation and flexible modification approaches. This subsection provides additional reasons for preferring the flexible movement approach.

Consider the (a)-examples in (69), which show that object shift goes hand in hand with a change in intonation pattern: while the sentence accent (indicated by small caps) is assigned to the direct object when it is part of the focus of the clause, it cannot be assigned to the direct object when it is part of the presupposition of the clause. The (b)-examples show that the two intonation patterns also occur with the same interpretive effect when the adverbial is absent. The symbols ⊂ and ⊄ are used to indicate “is (not) part of”.

| a. | dat | Peter | waarschijnlijk | het boek | koopt. | object ⊂ focus | |

| that | Peter | probably | the book | buys |

| a'. | dat | Peter | het boek | waarschijnlijk | koopt. | object ⊄ focus | |

| that | Peter | the book | probably | buys |

| b. | dat | Peter | het boek | koopt. | object ⊂ focus | |

| that | Peter | the book | buys |

| b'. | dat | Peter | het boek | koopt. | object ⊄ focus | |

| that | Peter | the book | buys |

The examples in (70), taken from Verhagen (1986), show more or less the same thing. These examples confirm the claim in Section N21.1.4, sub IC, that object shift of indefinite objects with a non-specific interpretation is normally impossible, while object shift of indefinite objects with a generic (or partitive) interpretation is obligatory; (70a) expresses that renting some bigger computer is probably necessary, while (70a') expresses that any computer bigger than the contextually defined standard should probably be rented (not bought). The (b)-examples illustrate again that these interpretations do not depend crucially on the presence of a clause adverbial, but on the intonation pattern of the clause.

| a. | Daarom | moet | hij | waarschijnlijk | een grotere computer | huren. | |

| therefore | must | he | probably | a bigger computer | rent |

| a'. | Daarom | moet | hij | een grotere computer | waarschijnlijk | huren. | |

| therefore | must | he | a bigger computer | probably | rent |

| b. | Daarom | moet | hij | een grotere computer | huren. | |

| therefore | must | he | a bigger computer | rent |

| b'. | Daarom | moet | hij | een grotere computer | huren. | |

| therefore | must | he | a bigger computer | rent |

The flexible movement approach can easily account for the correlation between the intonation pattern of the clause and the interpretation of the object in (69) and (70) by adopting the claim from Section 13.1, sub III, that the sentence accent must be assigned to some element within the lexical domain of the clause (unless it is phonetically empty). Because the shifted objects in the primed examples are not within the lexical domain, the sentence accent must be assigned to the clause-final verb; cf. Van den Berg (1978) for the same conclusion in different theoretical terms. It is not clear whether the two alternative approaches can account for this correlation. The flexible modification approach seems to leave us empty-handed, as within this approach there is no obvious link between adverb placement and the relevant correlation between intonation and interpretation. The same holds for the flexible base-generation approach as far as the (b)-examples in (69) and (70) are concerned: because the primeless and primed examples are assigned identical syntactic structures, there is no clear syntactic property that could account for the correlation between intonation and interpretation; cf. Verhagen (1986: §3.2.3) for a similar argument against Hoekstra’s (1984a: §2.7.3) hypothesis that object shift involves adjunction to VP, which we have not discussed here.

Subsection IA suggested that nominal argument shift is related to case marking or subject/object-verb agreement in that the subject and object optionally move into the specifier of certain functional heads responsible for the assignment of structural case agreement features: T for nominative case and subject-verb agreement features, and some functional head X for accusative case and object-verb agreement features (morphologically expressed in e.g. Italian and French, but invisible in Dutch). If true, this implies that nominal argument shift involves A-movement. This is consistent with the fact that this kind of movement seems to be restricted to nominal arguments; this was already noted in Kerstens (1975), Van den Berg (1978), and especially De Haan (1979), where a transformational rule of NP-preposing was proposed to account for these phenomena.

|

Nevertheless, it has been claimed that prepositional objects can undergo the same process; cf. Neeleman (1994a/1994b). An important reason for thinking that the leftward movement of such PPs should be distinguished from nominal argument shift has to do with the distribution of PPs containing a definite pronoun. First, recall from Subsection IB that definite subject/object pronouns normally undergo nominal argument shift because they refer to discourse-old entities. This is illustrated again in (72a), where the object pronoun haar can only follow the clause adverbial if it is assigned a contrastive accent: cf. Jan nodigt waarschijnlijk haar uit (niet hem) Jan will probably invite her (not him). Second, example (72b) shows that the leftward movement of a PP-complement is optional when its nominal part is a definite pronoun; this clearly shows that the division between discourse-old and discourse-new information has no bearing on the positioning of PP-complements. Finally, the leftward movement of the naar-PP produces a marked result when we replace nauwelijkshardly with the prototypical clause adverbial waarschijnlijkprobably, as in (72b'). This all shows that leftward movement of prepositional objects should be distinguished from nominal argument shift.

| a. | Jan nodigt | <haar> | waarschijnlijk <*haar> | uit. | |

| Jan invites | her | probably | prt | ||

| 'Jan will probably invite her.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Jan | <naar haar> | nauwelijks <naar haar> | kijkt. | |

| that | Jan | at her | hardly | looks | ||

| 'that Jan is hardly looking at her.' | ||||||

| b'. | dat | Jan | <??naar haar> | waarschijnlijk <naar haar> | kijkt. | |

| that | Jan | at her | probably | looks | ||

| 'that Jan is probably looking at her.' | ||||||

The examples in (73) further show that while shifted pronouns can be phonologically weak, the pronominal part of a shifted PP must be strong; cf. Ruys (2005: §2/2008: §1.2). The fact that the pronominal part can be weak if the PP follows the adverbial again shows that leftward movement of prepositional objects should be distinguished from nominal argument shift; cf. Section 9.5, sub IIIA, for a more detailed discussion.

| a. | Jan nodigt <ʼr> | waarschijnlijk <*ʼr> | uit. | ||

| Jan invites | her | probably | prt | ||

| 'Jan will probably invite her.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Jan | <*naar ʼr> | nauwelijks <naar ʼr> | kijkt. | |

| that | Jan | at her | hardly | looks | ||

| 'that Jan is hardly looking at her.' | ||||||

An important argument for an A-movement analysis of nominal argument shift can be based on anaphor binding and bound-variable readings of pronouns. The English subject-raising examples in (74) first show that A-movement is capable of feeding these binding relations; the crucial point is that in the primeless examples the noun phrase is clearly located within the infinitival clause and thus does not c-command the nominal complement of the to-PP, whereas in the primed examples the noun phrase has been A-moved into the subject position of the matrix clause, and consequently c-commands the reciprocal/possessive pronoun from this position; cf. Section 11.3.8, sub IIIA, for a more detailed discussion.

| a. | * | Therei seem to each other [ti to be some applicantsi eligible for the job]. |

| a'. | Some applicantsi seem to each other [t'i to be ti eligible for the job]. |

| b. | * | Therei seems to his mother [ti to be someone eligible for the job]. |

| b'. | Someonei seems to his mother [t'i to be ti eligible for the job]. |

For Dutch we can show the same by using constructions with dyadic unaccusative (nom-dat) verbs such as bevallento please in (75). Section 2.1.3 has shown that (as in the case of passive ditransitive constructions) the nominative-dative order in (75a) is the neutral one. The fact that subject shift feeds anaphor binding thus supports our claim that we are dealing with A-movement, i.e. that subject shift targets the regular subject position; cf. Vanden Wyngaerd (1989).

| a. | dat | <de jongen> | zichzelf <*de jongen> | goed | bevalt. | |

| that | the boy | himself | well | pleases | ||

| 'that the boy is quite pleased with himself.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | <de jongens> | elkaar <*de jongens> | goed | bevallen. | |

| that | the boys | each.other | well | please | ||

| 'that the boys are quite pleased with each other.' | ||||||

Consequently, the fact illustrated in (76) that object shift also feeds anaphor binding and bound-variable readings also strongly supports an A-movement analysis; cf. Vanden Wyngaerd (1988/1989).

| a. | * | Zij | heeft | namens elkaar | de jongens | gefeliciteerd. |

| she | has | on.behalf.of each other | the boys | congratulated |

| a'. | Zij | heeft | de jongensi | namens | elkaar ti | gefeliciteerd. | |

| she | has | the boys | on.behalf.of | each.other | congratulated | ||

| 'She congratulated the boys on behalf of each other.' | |||||||

| b. | * | Zij | heeft | namens | zijn begeleider | elke jongen | gefeliciteerd. |

| she | has | on.behalf.of | his supervisor | each boy | congratulated |

| b'. | Zij | heeft | elke jongeni | namens | zijn begeleider ti | gefeliciteerd. | |

| she | has | each boy | on.behalf.of | his supervisor | congratulated | ||

| 'She congratulated each boys on behalf of his supervisor.' | |||||||

Let us adopt the standard assumption that the direct object is base-generated within the VP, while VP adverbials are adjoined to the VP, as in (77a). Because the object is more deeply embedded than the adverbial phrase, the former does not c-command the latter, and this explains the fact, illustrated in the primeless examples in (76), that the direct object cannot bind the italicized pronominal elements within the adverbial phrase. If the vP-external landing site of object shift is an A-position, the contrast between the primeless and primed examples in (76) follows; in the resulting structure in (77b), the direct object c-commands the VP adverbial and is consequently able to bind the italicized pronominal elements within it. For a more detailed discussion of such cases, see Section N22.2, sub I/III.

| a. | ... [vP ... v [VP Adverb [VP DO V]]] |

| b. | ... [XP DO X [vP ... v [VP Adverb [VP tDO V]]]] |

There are also possible problems for an A-movement analysis. The fact, illustrated in (78), that leftward movement of the direct object licenses a parasitic gap is often considered an A'-movement property; cf. Bennis & Hoekstra (1984).

| a. | * | Zij | heeft | [zonder PRO pg | aan | te kijken] | de jongens | gefeliciteerd. |

| she | has | without | prt. | to look.at | the boys | congratulated |

| b. | Zij | heeft | de jongensi | [zonder PRO pg | aan | te kijken] ti | gefeliciteerd. | |

| she | has | the boys | without | prt. | to look.at | congratulated | ||

| 'She congratulated the boys without looking at them.' | ||||||||

Example (79) shows that things turn out to be even more complicated: leftward movement of the direct object can simultaneously feed binding and license a parasitic gap. Webelhuth (1989/1992) concluded from this that the dichotomy between A and A'-positions is too coarse, and that we need to assume a third, Janus-faced position that has properties of both A and A'-positions.

| a. | Zij | heeft | de jongensi | [zonder pg | aan te kijken] | namens elkaar | gefeliciteerd. | ||

| she | has | the boys | without | prt. to look.at | on.behalf.of each.other | congratulated | |||

| 'She congratulated the boys on behalf of each other without looking at them.' | |||||||||

| b. | Zij | heeft | elke jongeni | [zonder pg | aan te kijken] | namens zijn begeleider | gefeliciteerd. | ||

| she | has | each boy | without | prt. to look.at | on.behalf.of his supervisor | congratulated | |||

| 'She congratulated each boy on behalf of his supervisor without looking at him.' | |||||||||

Examples of this kind have led to heated debates about the nature of nominal argument shift and the licensing condition for parasitic gaps, but the main issues have not yet been settled. For example, the fact that infinitival clauses containing a parasitic gap usually precede PP-adjuncts containing an anaphor opens up the possibility that nominal argument shift is A-movement, which feeds anaphor binding, but that it may be followed by an additional A'-movement step that licenses the parasitic gap; cf. Mahajan (1990/1994). We will not digress on this issue here, but refer the reader to Section 11.3.8, sub III, for a detailed review of the debate.