- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Table 13 presents the subset of simple prepositions from Table 5 in Section 32.2.2 that can be used to express a spatial meaning. We have not included beneden because of the limited use of this preposition; cf. the remark below Table 5.

| aan | on | naar | towards | tot (en met) | until |

| achter | behind | naast | next to | tussen | between |

| bij | near | om | around | uit | out |

| binnen | inside | onder | under | van | from |

| boven | above | op | on(to)/at | vanaf | from |

| buiten | outside | over | across | vanuit | from out of |

| door | through | rond(om) | around | via | via |

| in | in(to) | tegen | against | voor | in front of |

| langs | along | tegenover | across | voorbij | past |

Spatial prepositions that are mainly used in official and written language are cases such as benoordento the north of (the more common counterparts are the phrasal prepositions ten noorden van), and the related formations bezijden, which only occurs in the fixed expression bezijden de waarheidfar from the truth, and benevensbesides, which bears an additional -s ending.

This section provides a semantic classification of the spatial prepositions in Table 13. Subsections I to III will show that these prepositions can be divided into three main groups: (i) deictic, (ii) absolute, and (iii) inherent prepositions. An even finer subdivision will be proposed on the basis of vector theory outlined in Section 32.3.1.1. An overview of the resulting classification is given in Subsection IV.

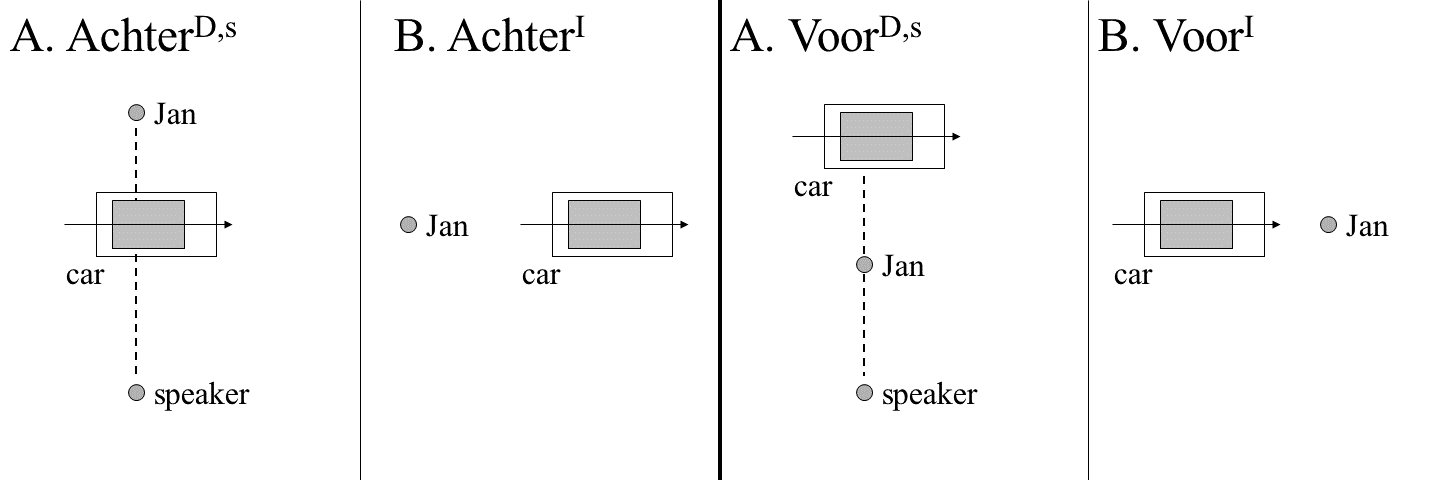

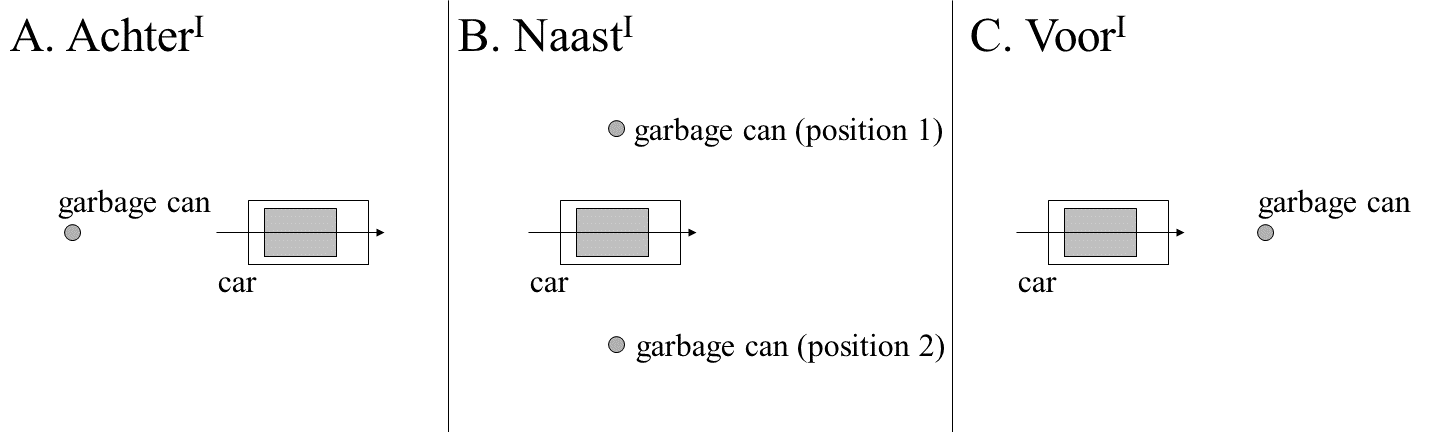

There are only three simple deictic prepositions: achterbehind, naastnext to, and voorin front of. In addition to these simple prepositions, there are two phrasal prepositions: links vanto the left of and rechts vanto the right of. These prepositions denote vectors with a magnitude greater than 0; they imply that there is no physical contact between the reference object and the located object.

| preposition | deictic | inherent | absolute | null vector |

| achter ‘behind’ | + | + | — | — |

| naast ‘next to’ | + | + | — | — |

| voor ‘in front of’ | + | + | — | — |

| links van ‘to the left of’ | + | + | — | — |

| rechts van ‘to the right of’ | + | + | — | — |

The prepositions in Table 14 can all be used inherently as well, so that their use can lead to ambiguity between the deictic and the inherent reading. This is illustrated in Figure 9 for the prepositions achter and voor in (186): the A-figures represent the deictic use with the speaker as the anchoring point, and the B-figures represent the inherent interpretations.

| Jan staat | achter/voor | de auto. | ||

| Jan stands | behind/in.front.of | the car | ||

| 'Jan stands behind/in front of the car.' | ||||

Note that the term “reading” is used here to express that there is nothing intrinsic in the prepositions achter and voor themselves or the construction in which they are used, that determines whether we are dealing with a deictic or an inherent reading; the intended interpretation depends on the perspective and intentions of the speaker, cf. Grabowski & Weiß (1995), Levelt (1996) and Beliën (2014). The same applies to the preposition naastnext to in (187a), which is ambiguous in the same way as achter and voor, but in addition denotes two separate areas that are opposite to each other. Because of the ambiguity between the deictic and the inherent reading, (187a) is consistent with Jan being in each of the four positions shown in Figure 10A&B.

| a. | Jan staat | naast | de auto. | |

| Jan stands | next.to | the car | ||

| 'Jan is standing next to the car.' | ||||

| b. | Jan staat | links/rechts | van | de auto. | |

| Jan stands | left/right | of | the car | ||

| 'Jan is standing to the left/right of the car.' | |||||

Figure 11 shows that the phrasal prepositions links van and rechts van in (187b) each refer to only two of these four positions.

The deictic interpretation of the prepositions achterbehind and voorin front of is excluded as soon as they are combined with prepositions such as aanon, inin, or opon, which can only be used inherently; cf. Section 32.3.1.2, sub III. This is illustrated in (188) for achter and voor, which can only be used to refer to the A-representations in Figure 12.

| Jan zit achter/voor | op de auto. | ||

| Jan sits behind/in.front.of | on the car | ||

| 'Jan is sitting on the back/front of the car.' | |||

Section 34.1.3 will argue that achterop and voorop are compounds. For completeness, it should be noted that aan/op/in cannot be combined with naastnext to: cf. *naastaan, *naastop, *naastin.

The examples in (189), finally, show that the PPs headed by the deictic prepositions in Table 14 can be used both to indicate a location, as in (189a), and a change of location, as in (189b).

| a. | De vuilnisbak | staat | achter/naast/voor | de auto. | |

| the garbage.can | stands | behind/next.to/in.front.of | the car | ||

| 'The trash can is behind/next to/in front of the car.' | |||||

| b. | Jan zet | de vuilnisbak | achter/naast/voor | de auto. | |

| Jan puts | the garbage.can | behind/next.to/in.front.of | the car | ||

| 'Jan puts the trash can behind/next to/before the car.' | |||||

Unlike the deictic and the inherent interpretations, the absolute interpretation does not require information about the reference object and/or an external anchoring point; minimal information about the natural environment (such as what the position of the earth or magnetic north is) is sufficient to interpret these prepositions correctly. The absolute prepositions can be divided into two groups, which differ in that the first refers to a (change of) location, whereas the second is directional.

The group of absolute prepositions denoting a (change of) location is given in Table 15. These prepositions denote vectors with a magnitude greater than 0; they usually imply that there is no physical contact between the reference object and the located object (but see below). We will see that in some contexts, these prepositions also allow (at least marginally) a directional reading.

| preposition | deictic | inherent | absolute | null vector | locational | directional |

| boven | — | — | + | — | + | — |

| om | — | — | + | — | + | ? |

| onder | — | — | + | — | + | ? |

| rond | — | — | + | — | + | ? |

| tussen | — | — | + | — | + | ? |

Some examples of PPs headed by these prepositions are given in (190).

| a. | De lamp | hangt | boven | de kast. | |

| the lamp | hangs | above | the cupboard |

| b. | De bal | ligt | onder | de kast. | |

| the ball | lies | under | the cupboard |

| c. | De lamp | staat | tussen | twee vazen. | |

| the lamp | stands | between | two vases |

| d. | De mannen | zitten | om | de tafel. | |

| the men | sit | around | the table |

| e. | De kaarsen | staan | rond | de kerststal. | |

| the candles | stand | around | the crib |

Before we discuss the absolute meaning of the prepositions in Table 15 in more detail, we turn to a number of special uses of them. First, the idiomatic expressions with boven in (191) seem to have a directional flavor.

| a. | Dat | gaat | mij | boven de pet. | |

| that | goes | me | above the cap | ||

| 'That is over my head /I donʼt understand that.' | |||||

| b. | Hij | groeit | mij | boven het hoofd. | |

| he | grows | me | above the head | ||

| 'Heʼs outgrowing me/Heʼs leaving me standing.' | |||||

The same thing seems to hold for the idiomatic constructions in (192a), in which the adposition boven is preceded by the preposition te. Similar idiomatic constructions are possible with the non-directional inherent prepositions binneninside and buitenoutside, as shown in (192b&c); this will be discussed in Subsection III.

| a. | Dit | gaat | mijn verstand | te boven. | |

| this | goes | my understanding | te above | ||

| 'This is beyond my power of reasoning.' | |||||

| b. | Dat | schoot | me | net | te binnen. | |

| that | rushed | me | just | te inside | ||

| 'This just came to me/I just remembered this.' | ||||||

| c. | Dit | gaat | alle perken | te buiten. | |

| this | goes | all boundaries | te outside | ||

| 'This oversteps all bounds.' | |||||

The preposition onder seems to denote the null vector in the idiomatic construction zitten + [PP onder ...] in (193a), which expresses that the bird is covered with oil. That this is an idiom is clear from the fact that the preposition onder has no paradigm; it cannot be replaced by any other spatial preposition. Other constructions in which physical contact seems to be implied are given in the (b)-examples in (193); the (c)-examples show that in these examples onder functions as the antonym of the inherent preposition op, not of boven. This shows that onder can be used both as an absolute preposition and as an inherent preposition (with a different paradigm); here we only discuss the former use.

| a. | De vogel | zit | onder de olie. | |

| the bird | sits | under the oil | ||

| Idiomatic: 'The bird is covered in oil.' | ||||

| b. | Jan ligt | onder de dekens. | |||

| Jan lies | under the blankets | ||||

| 'Jan is lying under the blankets. | |||||

| b'. | Jan ligt | onder me. | |||

| Jan lies | under me | ||||

| 'Jan is lying under me.' | |||||

| c. | Jan ligt op/?boven de dekens. | ||

| Jan lies on/above the blankets | |||

| 'Jan is lying on the blankets.' | |||

| c'. | Jan ligt op/*boven me. | ||

| Jan lies on/above me | |||

| 'Jan is lying on top of me.' | |||

The preposition om can also occasionally involve physical contact; this is especially true in the case of jewelry and pieces of clothing, as illustrated in (194a). The possessive dative construction in (194b) seems idiomatic again. Since we have little to say about such cases, we will ignore them in the following discussion, while leaving open the question of whether or not om can denote the null vector.

| a. | De ketting | zit | om | zijn enkel. | |

| the chain | sits | around | his ankle | ||

| 'The chain is around his ankle.' | |||||

| b. | Hij | vloog | haar | om de nek. | |

| he | flew | her | around the neck | ||

| 'He ran towards her and flung his arms around her neck.' | |||||

Finally, the examples in (195) show that, like the deictic prepositions achterbehind and voorin front of, the absolute prepositions boven and onder can be combined with the inherent prepositions opon and inin. The resulting sequences must be interpreted inherently and denote the null vector.

| a. | bovenop | ‘on top of’ |

| a'. | bovenin | ‘at the top of’ |

| b. | onderop | ‘at the bottom of’ |

| b'. | onderin | ‘at the bottom of’ |

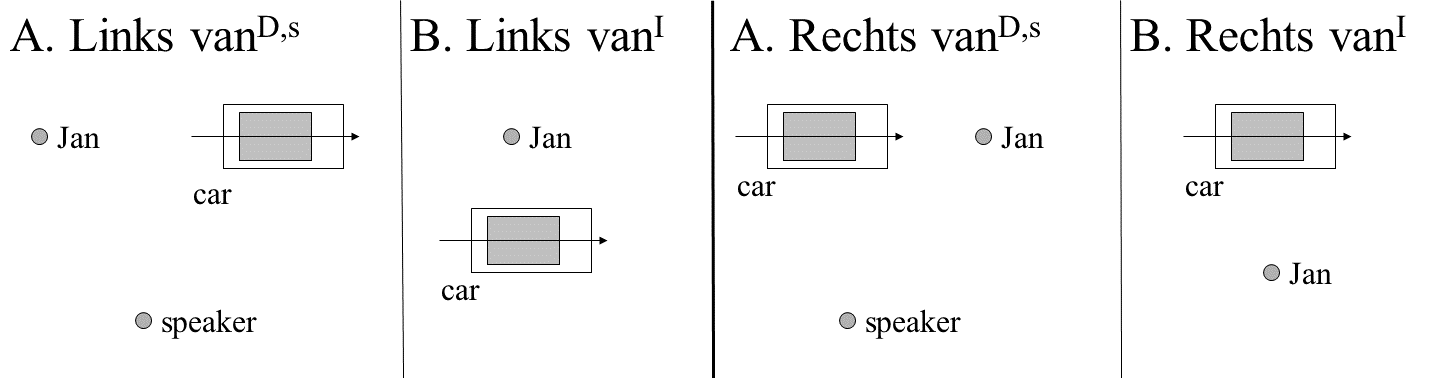

Let us now turn to the more common absolute interpretations of the prepositions bovenabove, omaround, onderbeneath, rondaround and tussenbetween in Table 15. PPs headed by these prepositions can usually be interpreted without the presence of an external anchoring point and without the need to appeal to the dimensional properties of the reference object (which we therefore represent as a point in Figure 13 below). However, to interpret the PPs headed by boven and onder, we do need some information about the natural environment; as is shown in Figure 13A, we need to know where the earth’s surface is located. Figure 13B&C shows that such minimal information is not even required to interpret the prepositions omaround, rondaround and tussenbetween.

Note that the preposition tussenbetween is special in that it usually requires a plural complement; the position of the located object is calculated on the basis of at least two reference objects. This property is also found with the preposition halverwege in (196a), although this preposition differs in that it can also refer to a certain position of the reference object; in example (196b), the position of the located object is computed on the basis of the boundaries (in this case, the bottom and the top of the ladder) of the reference object.

| a. | Jan woont | halverwege/tussen | Groningen en Zuid-Laren. | |

| Jan lives | halfway/between | Groningen and Zuid-Laren |

| b. | Jan staat | halverwege/*tussen | de ladder. | |

| Jan stands | halfway/between | the ladder |

There are some exceptions to the general rule that the complement of tussenbetween is plural. In (197), for example, tussen takes the singular noun phrase de deurthe door as its complement. However, what is actually claimed is that Janʼs finger got jammed between the door and the doorpost.

| Jan kreeg | zijn vinger | tussen de deur. | ||

| Jan got | his finger | between the door |

In many cases, PPs headed by om refer to areas in only two dimensions, as in the lefthand figure in Figure 13C, while PPs headed by rond refer to areas in three dimensions, as in the righthand figure. In other cases, however, the difference between the two cases is not so clear, and both om and rond seem to be equally well applicable to both situations in Figure 13C (and the same seems to hold for the complex preposition rondom); the examples in (198), for instance, seem almost equivalent.

| a. | De padvinders | zitten | om het vuur. | |

| the scouts | sit | around the fire |

| b. | De padvinders | zitten | rond het vuur. | |

| the scouts | sit | around the fire |

However, it is not the case that om and rond are always interchangeable. In examples such as (199a), om is possible while rond gives rise to a degraded result; note that Zwarts (2006), which proposes a number of semantic restrictions on the use of om and rond, assigns a mere question mark to the example with rond.

| Jan woont | om/*rond de hoek. | ||

| Jan lives | around the corner |

The examples in (190) have already shown that PPs headed by the prepositions in Table 15 can be used to indicate a location. Their causative counterparts in (200) show that these PPs can also be used to indicate a change of location.

| a. | Jan hangt | de lamp | boven | de kast. | |

| Jan hangs | the lamp | above | the cupboard |

| b. | Jan legt | de bal | onder | de kast. | |

| Jan puts | the ball | under | the cupboard |

| c. | Jan zet | de lamp | tussen | twee vazen. | |

| Jan puts | the lamp | between | two vases |

| d. | Jan wikkelt | de ketting | om | zijn enkel. | |

| Jan winds | the chain | around | his ankle |

| e. | Jan zet | kaarsen | rond | de kerststal. | |

| Jan puts | candles | around | the crib |

Intuitions are not very sharp, but it seems that, with the exception of boven, the prepositions under discussion can also be used directionally. One indication of this is that they can, at least marginally, occur as the complement of a verb of traversing, such as rijdento drive in (201).

| a. | Jan is ??onder/*boven | de brug | gereden. | |

| Jan is under/above | the bridge | driven |

| b. | ?? | Jan is tussen | de bomen | gereden. |

| Jan is between | the trees | driven |

| c. | Jan is om/?rond | het meer | gereden. | |

| Jan is around | the lake | driven |

Note in passing that the marginal examples become fully acceptable when rijden takes the auxiliary hebben in the perfect tense, but then rijden is just an activity verb and the PP functions as an adverbial phrase of place. The same is true for boven, as the following example shows: Het zweefvliegtuig heeft/*is boven de hei gevlogenThe glider has flown over the heath. We should therefore ignore such cases.

A clearer indication that these prepositions can be interpreted directionally is that most of them can head PPs with an extent reading. For examples (202a&b), it could be argued that the preposition is an abbreviation of the circumposition P ... door, but this is certainly not possible for om and rond in (202c).

| a. | De weg | loopt | onder | de brug | ?(door). | |

| the road | goes | under | the bridge | door |

| b. | De weg | loopt | tussen | de bomen | ?(door). | |

| the road | goes | between | the trees | door |

| c. | De weg | loopt | om/rond | het meer | (*door). | |

| the road | goes | around | the lake | door |

The more or less formal preposition tein/at probably also belongs to the group of absolute prepositions. A PP headed by te appears to be interpreted preferably as denoting a location, as in (203a), but the examples in (203b&c) show that such PPs can sometimes also refer to a change of location. Given the formal nature of te, it is not surprising that there are several fixed expressions involving a change of location; an example with the archaic case form ter is given in (203d). The archaic examples in (192) above even suggest that PPs headed by te can also be directional in nature.

| a. | Jan woont | te Amsterdam. | location | |

| Jan lives | in Amsterdam |

| b. | Jan raakte | te water. | change of location | |

| Jan got | in water | |||

| 'Jan got into the water.' | ||||

| c. | Jan vestigt | zich | te Amsterdam. | (change of) location | |

| Jan settles | refl | in Amsterdam |

| d. | We | hebben | hem | gisteren | ter aarde | besteld. | |

| we | have | him | yesterday | into.the earth | delivered | ||

| 'We buried him yesterday.' | |||||||

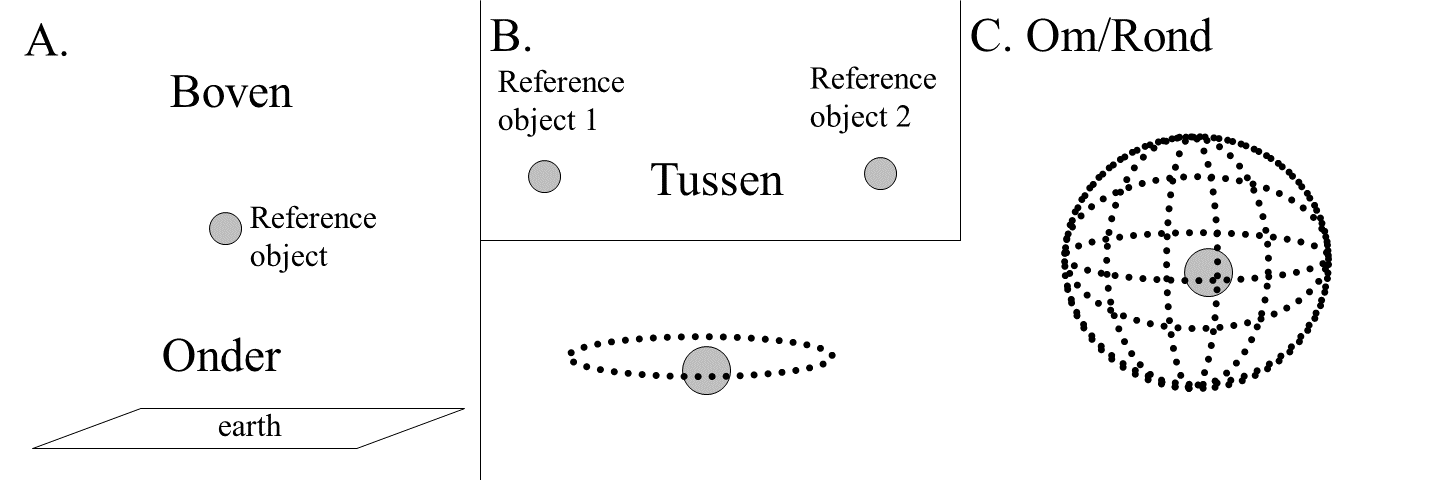

The above discussion of the absolute locational prepositions has shown that the absolute prepositions boven and onder, together with the deictic prepositions discussed in Subsection I, provide an exhaustive (but not necessarily complementary) division of space; cf. the Cartesian-style coordinate system in Figure 14.

If we take the intersection of the three axes to represent the position of the reference object, six areas can be distinguished. The areas called voorin front of and achterbehind, bovenabove and onderabove and links vanto the left of and rechts vanto the right of do not overlap; they are true antonyms. The others, on the other hand, can overlap, as can be seen from the fact that combinations like rechts bovenright above, links achterleft behind and ?voor onderin front under can be found. Adpositions of the kind in Figure 14, including tussenbetween, are called projective prepositions in Zwarts (1997b).

We conclude this subsection with three brief remarks about Figure 14. First, this figure also shows that naastnext to is used when the left/right distinction is not relevant; similar “neutral” prepositions do not exist for voor/achter and boven/onder. Second, in addition to the areas denoted by these six “basic” prepositions in Figure 14, other areas can be denoted by prepositions like tussenbetween and om/rondomaround; cf. Figure 13B&C above. Finally, it should be noted that there are alternative ways to divide space, e.g. by using absolute phrasal prepositions like ten noorden/oosten/zuiden/westen vanto the north/east/south/west of.

The absolute directional prepositions in Table 16 usually do not denote a (change of) location, but a direction (a movement along a path). Because the located object is not at a fixed location but on a path (an ordered sequence of vectors), they do not involve the null vector by definition.

| preposition | deictic | inherent | absolute | null vector | locational | directional |

| naar | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| tot (en met) | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| van | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| vanaf | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| vanuit | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| over (I) | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| via | — | — | + | — | — | + |

| voorbij | — | — | + | — | — | + |

PPs headed by the prepositions in Table 16 usually do not refer to a location, as is clear from the fact that they cannot be the complements of location verbs such as liggento lie or change-of-location verbs such as leggento put. This is illustrated in (204) for PPs headed by naarto, vanfrom and viavia.

| a. | * | Het boek | ligt | naar | de boekenkast. |

| the book | lies | to | the bookshelves |

| a'. | * | Jan legt | het boek | naar | de boekenkast. |

| Jan puts | the lamp | to | the bookshelves |

| b. | * | Het boek | ligt | van | de boekenkast. |

| the book | lies | from | the bookshelves |

| b'. | ? | Jan legt | het boek | van | de boekenkast. |

| Jan puts | the book | from | the bookshelves |

| c. | * | Het boek | ligt | voorbij | de boekenkast. |

| the book | lies | past | the bookshelves |

| c'. | * | Jan legt | het boek | voorbij | de boekenkast. |

| Jan puts | the book | past | the bookshelves |

The fact that example (204b') is relatively good may be due to the fact that van can sometimes be used in as an abbreviation of the circumposition van ... af. Note also that the preposition voorbij can be used in geographical localizations of a building or a geographical entity (city, village mountain, etc.); the speaker has in mind a path that extends from his current position to the located object, which is then located with respect to the reference object that is also on that path. An example is given in (205a). Another possible counterexample to the claim that the prepositions in Table 16 are not locational is the possessive dative construction in (205b), which is usually interpreted metaphorically. That we are dealing with a more or less fixed expression is shown by the fact that it does not alternate with the construction in (205b'), in which the possessive relation is expressed by a possessive pronoun; cf. the discussion in Section V3.3.1.4.

| a. | Goirle ligt | even | voorbij | Tilburg. | |

| Goirle lies | just | past | Tilburg |

| b. | Het water | staat | hem | aan | de lippen. | |

| the water | stands | him | to | the lips | ||

| 'Heʼs in great difficulties.' | ||||||

| b'. | * | Het water | staat | aan | zijn lippen. |

| the water | stands | to | his lips |

Whereas PPs headed by the prepositions in Table 16 normally do not occur as complements of (change of) location verbs, they do occur as the complement of verbs of traversing like rijdento drive, fietsencycling, and lopento walk.

| a. | Jan | reed | naar Groningen. | |

| Jan | drove | to Groningen |

| a'. | Jan | is | naar Groningen | gereden. | |

| Jan | has | to Groningen | driven |

| b. | Jan | fietst | van Utrecht ?(naar Groningen). | |

| Jan | cycles | from Utrecht to Groningen |

| b'. | Jan | is | van Utrecht ?(naar Groningen) | gefietst. | |

| Jan | has | from Utrecht to Groningen | cycled |

| c. | Jan | reed | voorbij Groningen. | |

| Jan | drove | past Groningen |

| c'. | Jan | is | voorbij Groningen | gereden. | |

| Jan | has | past Groningen | driven |

The examples in (207) show that these prepositions also occur with unaccusative verbs like vertrekkento leave, komento come, and gaanto go. This need not surprise us, as the verbs of traversing in (206) also behave like unaccusatives: for example, they must take the auxiliary zijnto be in the perfect tense.

| a. | Jan vertrok/ging | naar Groningen. | |

| Jan left/went | to Groningen |

| b. | Jan vertrekt/komt | van Utrecht. | |

| Jan leaves/comes | from Utrecht |

| c. | Jan kwam | voorbij Groningen | |

| Jan came | past Groningen |

Note that when the verbs in (206) take the perfect auxiliary hebben, they no longer behave like verbs of traversing but like activity verbs; the concomitant result, shown in (208), is that the PPs headed by the prepositions in Table 16 are degraded. Note that (208b) is acceptable if the phrase van Utrecht naar Groningen is interpreted restrictively in the sense that it implies that Jan did something else (e.g. cycling) during the rest of the journey: Jan heeft van Utrecht naar Groningen gereden maar van Groningen naar Lauwersoog gewandeldJan drove from Utrecht to Groningen, but he walked from Groningen to Lauwersoog; this reading is not relevant here.

| a. | Jan | heeft | (*naar Groningen) | gereden. | |

| Jan | has | to Groningen | driven |

| b. | Jan | heeft | (#van Utrecht naar Groningen) | gereden. | |

| Jan | has | from Utrecht to Groningen | driven |

| c. | Jan | heeft | (*voorbij Groningen) | gereden. | |

| Jan | has | past Groningen | driven |

The directional prepositions can be divided into three groups. The first group takes the reference object as the endpoint of the implied path. The second group, on the other hand, takes the reference object as the starting point of the path. Finally, the prepositions of the third group denote a path that includes the reference object. This can be represented by the two features [±from] and [±to].

| a. | [-from] [‑to]: locational adpositions |

| b. | [‑from] [+to]: naar ‘to’; tot ‘until’; in de richting van ‘in the direction of’ |

| c. | [+from] [‑to]: van ‘from’; vanuit ‘from out of’; vanaf ‘from’ |

| d. | [+from] [+to]: via ‘via’; over ‘over’; voorbij ‘past’ |

The feature combination in (209a) denotes the set of prepositions that are not directional, i.e. the locational adpositions. The three others divide the directional adpositions into three subclasses depending on the location of the reference object. The last three subclasses will be discussed in the following subsections.

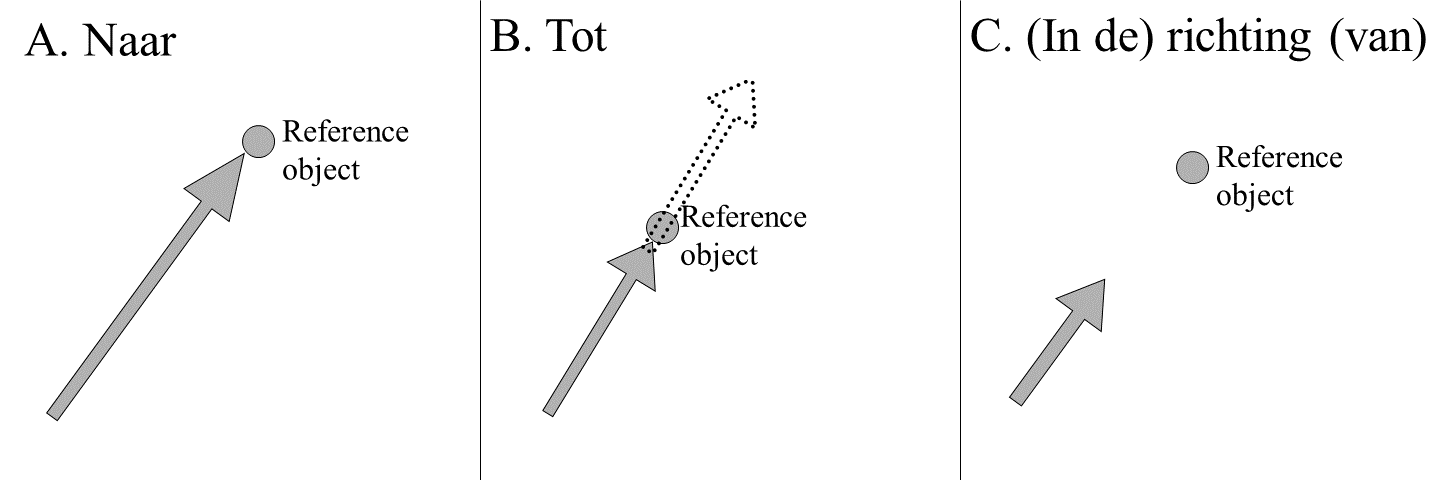

The complement of the preposition naarto refers to the endpoint of a complete path, with the implication that it will be reached sooner or later. The complement of the preposition tot (en met)until denotes an arbitrary point on an implied path, with the implication that this point is the endpoint of a distinct subpart of the complete path. In other words, while example (210a) suggests that both Jan and Peter will go to Groningen (see Figure 15A), example (210b) suggests that at least one of the two participants will continue his journey beyond Groningen (in Figure 15B the dotted arrow indicates the remainder of the path that either Jan or Peter will take). The difference between tot and tot en met is that in the latter case the relevant part of the path includes the position referred to by the reference object, whereas in the former case it can be excluded. Note that the (reduced version of the) phrasal preposition in de richting van only indicates the direction of the path, without implying that the reference object will ever be reached (see Figure 15C).

| a. | Jan rijdt | met Peter | mee | naar Groningen. | |

| Jan drives | with Peter | with | to Groningen | ||

| 'Peter takes Jan with him to Groningen.' | |||||

| b. | Jan | rijdt | met Peter | mee | tot Groningen. | |

| Jan | drives | with Peter | with | until Groningen | ||

| 'Peter will drive Jan as far as Groningen.' | ||||||

| c. | Jan rijdt | (in de) | richting | (van) | Groningen. | |

| Jan drives | in the | direction | of | Groningen |

PPs headed by the prepositions naarto and in de richting vantowards are special in that they also allow an orientation reading. This is illustrated in (211). The two examples differ in that only in (211a) is the reference object actually pointed at.

| a. | Jan wijst | naar de kerk. | |

| Jan points | to the church |

| b. | Jan wijst | in de richting van de kerk. | |

| Jan points | in the direction of the church |

The PPs can be used as attributive modifiers with a similar distinction: according to (212a) the road will lead up to the church, while this need not be the case in (212b). Note that PPs headed by tot cannot usually be used as attributive modifiers; we will return to this in our discussion of example (217).

| a. | de weg | naar de kerk | |

| the road | to the church |

| b. | de weg | in de richting van de kerk | |

| the road | in the direction of the church |

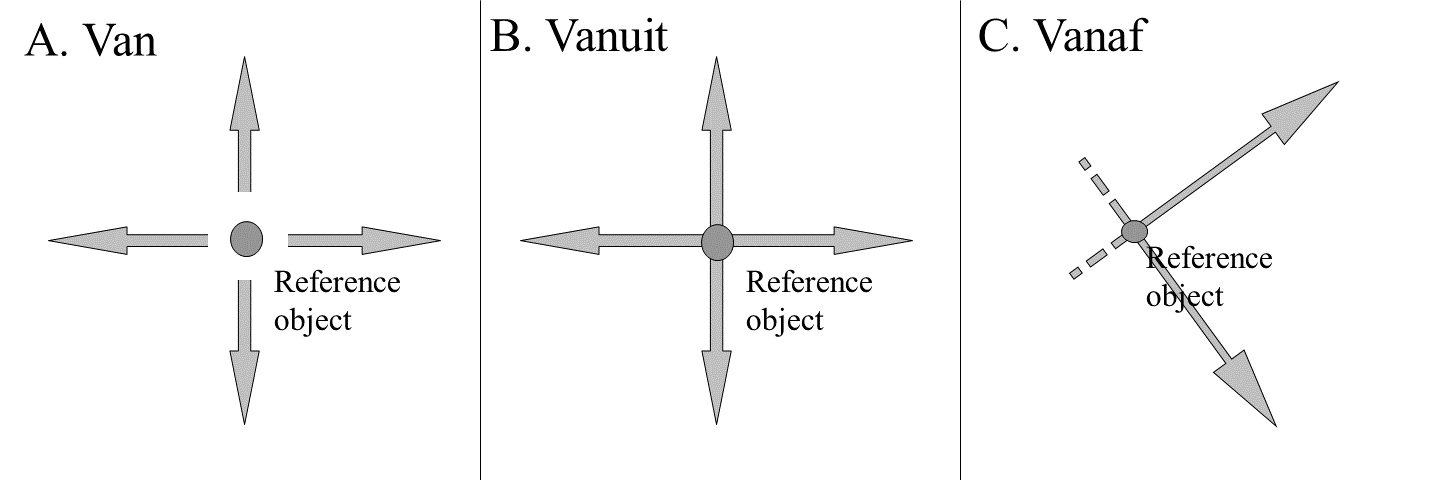

The prepositions van, vanaf, and vanuit take a nominal complement that refers to the starting point of (a subpart of) the implied path; in Figure 16 we indicate this by drawing several arrows from the reference object.

Van is the most neutral of these three prepositions; it simply expresses that there is a path starting from the reference object without necessarily implying that the reference object is included in the path; vanuit, on the other hand, expresses that (a area within) the reference object is included in the path; vanaf indicates that the path may have started at another location, but that only the part from the reference object onward is considered relevant; in this respect, this preposition is similar to tot (en met).

| a. | dat | Jan morgen | van Utrecht | ?(naar Groningen) | rijdt. | |

| that | Jan tomorrow | from Utrecht | to Groningen | drives | ||

| 'that Jan will drive from Utrecht to Groningen tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan morgen | vanuit Utrecht | (naar Groningen) | vertrekt. | |

| that | Jan tomorrow | from.out.of Utrecht | to Groningen | departs | ||

| 'that Jan will head for Groningen from Utrecht tomorrow.' | ||||||

| c. | dat | Jan morgen | vanaf Utrecht | met de trein | (naar Groningen) | gaat. | |

| that | Jan tomorrow | from Utrecht | with the train | to Groningen | goes | ||

| 'From Utrecht (on) Jan will go to Groningen by train tomorrow.' | |||||||

The prepositions van, vanaf, and vanuit leave the endpoint of the path, and thus also the direction of the path, unspecified; to specify the direction, we have to add a PP that refers to the endpoint of (the relevant part of) the path. A comparison of the examples in (213) and (214) shows that the two PPs are strictly ordered: PPs denoting the starting point must precede PPs denoting the endpoint of the path.

| a. | * | dat | Jan morgen | naar Groningen | van Utrecht | rijdt. |

| that | Jan tomorrow | to Groningen | from Utrecht | drives |

| b. | * | dat | Jan morgen | naar Groningen | vanuit Utrecht | vertrekt. |

| that | Jan tomorrow | to Groningen | from.out.of Utrecht | departs |

| c. | * | dat | Jan morgen | naar Groningen | vanaf Utrecht | met de trein | gaat. |

| that | Jan tomorrow | to Groningen | from Utrecht | with the train | goes |

The examples in (215) show that this holds not only for their relative position in the middle field of the clause, but also for their relative orderings under topicalization (although contrastive focus on the topicalized part may improve the orderings in the primed examples, especially in generic contexts).

| a. | Van Utrecht rijdt Jan morgen naar Groningen. |

| a'. | * | Naar Groningen rijdt Jan morgen van Utrecht. |

| b. | Vanuit Utrecht vertrekt Jan morgen naar Groningen. |

| b'. | * | Naar Groningen vertrekt Jan morgen vanuit Utrecht. |

| c. | Vanaf Utrecht gaat Jan morgen met de trein naar Groningen. |

| c'. | * | Naar Groningen gaat Jan morgen vanaf Utrecht met de trein. |

In the examples discussed above, the located object actually traverses the path denoted by the spatial PPs. This need not always be the case, as can be seen from the primeless examples in (216), which involve extent readings of the directional PPs. The same extent readings are found in the primed examples in which the PPs function as modifiers of a noun phrase.

| a. | De weg | loopt | van Utrecht | ?(naar Groningen). | |

| the road | walks | from Utrecht | to Groningen | ||

| 'The road runs from Utrecht to Groningen.' | |||||

| a'. | de weg | van Utrecht | ??(naar Groningen) | |

| the road | from Utrecht | to Groningen |

| b. | De weg | loopt | vanuit | Utrecht | (naar Groningen). | |

| the road | walks | from.out.of | Utrecht | to Groningen | ||

| 'The road starts in Utrecht and runs to Groningen.' | ||||||

| b'. | de weg | vanuit | Utrecht | (naar Groningen) | |

| the road | from.out.of | Utrecht | to Groningen |

Example (217a) shows that PPs headed by the directional preposition vanaf cannot easily be used as modifiers of the noun phrase. In Subsection 1, we noted the same thing for the preposition tot; this is illustrated again in (217b). This strongly suggests that PPs referring to a subpart of some larger implied path cannot be used as modifiers in the noun phrase, although it should immediately be noted that noun phrases modified by tot-PPs are common when the reference object is abstract, as in (217b').

| a. | *? | de weg | vanaf Utrecht | (naar Groningen) |

| the road | from Utrecht | to Groningen |

| b. | *? | de weg | tot Groningen |

| the road | until Groningen |

| b'. | de weg | tot inzicht/de waarheid/God | |

| the road | to understanding/the truth/God |

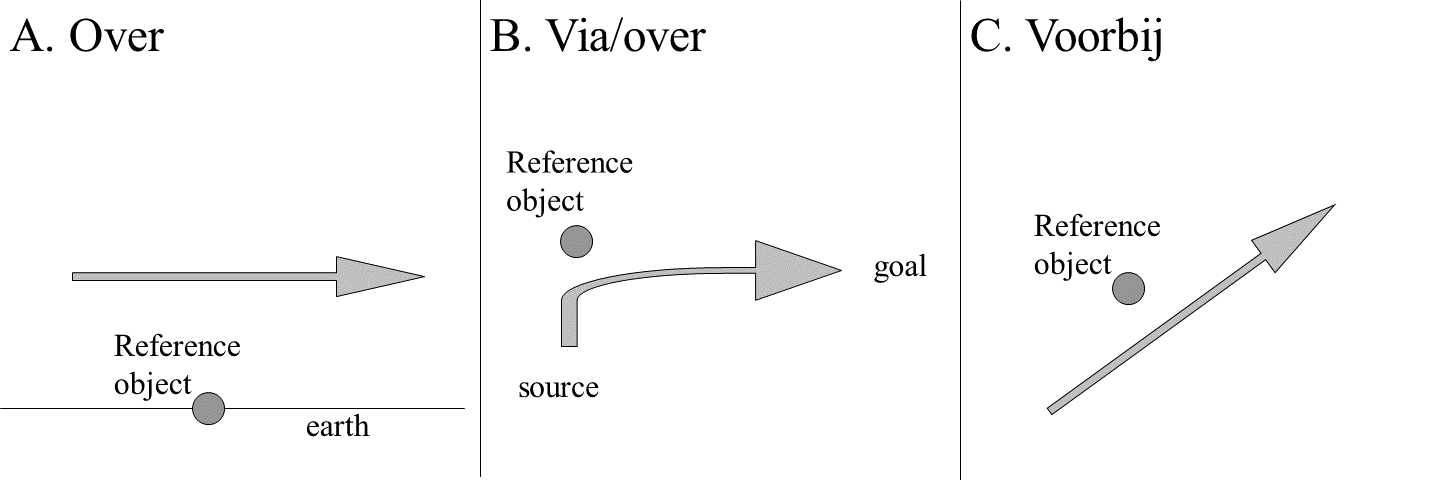

The nominal objects of the prepositions over, via, and voorbij do not refer to the beginning or the end of the path, but just simply to an arbitrary point on the path. In a sense, these prepositions locate the path with respect to the reference object. This could be described by dividing the relevant path into two subparts, with the reference object being the endpoint of the first subpart and the starting part of the second subpart. This is shown in Figure 17 for the examples in (218).

| a. | dat | het vliegtuig | over | de Alpen | vliegt. | |

| that | the airplane | over | the Alps | flies |

| b. | dat | Jan (van Amsterdam) | via/over Utrecht | (naar Groningen) | rijdt. | |

| that | Jan from Amsterdam | via/over Utrecht | to Groningen | drives | ||

| 'that Jan drives from Amsterdam to Groningen via Utrecht.' | ||||||

| c. | dat | Jan voorbij die boom | liep. | |

| that | Jan past that tree | walked | ||

| 'that Jan walked past that tree.' | ||||

Example (218b) contains three PPs: a van-PP referring to the starting point of the path, which is followed by the via/over-PP referring to a specific intermediate point, and a naar-PP referring to the endpoint. The examples in (219) show that, with a non-contrastive intonation pattern, these PPs must be placed in this order, i.e. the orders in the primed examples are severely degraded; cf. also the discussion of (214).

| a. | dat | Jan van Amsterdam via/over Utrecht naar Groningen rijdt. |

| b. | ?? | dat Jan van Amsterdam naar Groningen via/over Utrecht rijdt. |

| c. | ?? | dat Jan via/over Utrecht van Amsterdam naar Groningen rijdt. |

Finally, the examples in (220) show that the located object need not actually traverse the path denoted by the spatial PPs; these PPs can also receive an extent reading.

| a. | De weg | loopt via/over Utrecht | naar Groningen. | |

| the road | walks via/over Utrecht | to Groningen | ||

| 'The road goes via Utrecht to Groningen.' | ||||

| b. | de weg | via Utrecht | naar Groningen | |

| the road | via Utrecht | to Groningen |

Inherent prepositions are interpreted in relation to the dimensional properties of the reference object itself (i.e. the complement of the preposition). The four subsets in (221) can be distinguished; these will be discussed in the following subsections.

| a. | Prepositions denoting a set of vectors that situate the located object relative to: |

| (i) | the dimensions mentally attributed to the reference object: achter ‘behind’, naast ‘next to’, voor ‘in front of’ and tegenover ‘opposite’ |

| (ii) | the physical dimensions of the reference object: langs ‘along’, binnen ‘within/inside’, buiten ‘outside’, bij ‘near’ |

| b. | Prepositions denoting the null vector: |

| (i) | the located object is (partly) inside the reference object: in ‘in’, uit ‘out of’, door ‘through’ |

| (ii) | the located object is in contact with the reference object: aan ‘on’, op ‘on’, over (II) ‘over’, tegen ‘against’ |

We start by considering prepositions that denote a set of vectors. The two sets of prepositions belonging to this group situate the located object with respect to the reference object, without implying that there is physical contact between the two. Two groups can be distinguished: prepositions situating the located object according to the dimensions mentally attributed to the reference object, and prepositions situating the located object according to the physical dimensions of the reference object.

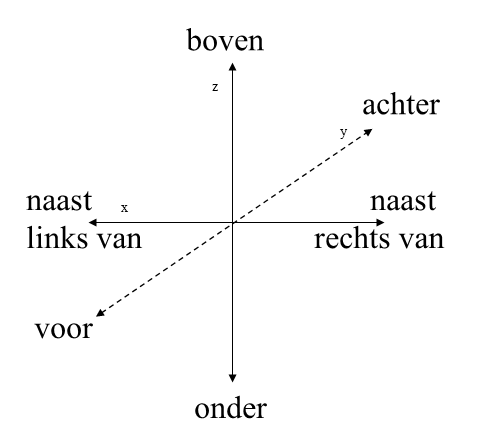

Subsection I has shown that the prepositions achterbehind, naastnext to and voorin front of can be used both deictically and inherently. The inherent uses of these prepositions in the examples in (222) indicate that the object is (put) in the positions indicated in Figure 18.

| a. | De vuilnisbak | staat | achter/naast/voor | de auto. | |

| the garbage.can | stands | behind/next.to/in.front.of | the car | ||

| 'The trash can is behind/next to/in front of the car.' | |||||

| b. | Jan zet | de vuilnisbak | achter/naast/voor | de auto. | |

| Jan puts | the garbage.can | behind/next.to/in.front.of | the car | ||

| 'Jan puts the trash can behind/next to/in front of the car.' | |||||

The computation of the position of the located object depends on what is considered to be the back or the front of the reference object. This is largely a matter of convention, in the sense that the dimensional properties of the reference object do not matter. Some examples: the front of a car is determined by the direction in which the car normally drives, the front of a building is usually determined by its main entrance, and the front of a television is determined by the placement of the screen. Other factors may also be involved, as can be seen by comparing the examples in (223).

| a. | Jan zit | voor | de televisie. | |

| Jan sits | in.front.of | the television | ||

| 'Jan is watching television.' | ||||

| b. | Jan zit | achter | zijn computer. | |

| Jan sits | behind | his computer | ||

| 'Jan is working on his computer.' | ||||

Although the examples in (223) imply that Jan is in similar positions with respect to the two screens, antonymous prepositions are used. This is because achter is often used to in contexts where one is operating the reference object, as in the following examples.

| a. | Jan zit | achter | het stuur. | |

| Jan sits | behind | the steering wheel | ||

| 'Jan is driving the car.' | ||||

| b. | Jan zit | achter | de piano. | |

| Jan sits | behind | the piano | ||

| 'Jan is playing the piano.' | ||||

| c. | Jan zit | achter de knoppen. | |

| Jan sits | behind the buttons | ||

| 'Jan controls everything.' | |||

Another preposition that belongs to this group of inherent prepositions is the compound tegenoveropposite. It differs from prepositions like achter, naast, and voor in that it refers not only to the orientation of the reference object, but also to that of the located object; the reference and the located object must be facing each other. This is illustrated in example (225a), which refers to the situation in Figure 19A, where Jan and Peter are facing each other. Note that this situation can also be described by example (225b), but the difference between the two cases is that the orientation of the located object is not relevant in the case of voor; Figure 19B shows that (225b) can be applied to a wider range of situations than (225a).

| a. | Peter staat | tegenover | Jan. | |

| Peter stands | opposite | Jan | ||

| 'Peter is standing opposite Jan.' | ||||

| b. | Peter staat | voor | Jan. | |

| Peter stands | in.front.of | Jan | ||

| 'Peter is standing in front of Jan.' | ||||

Related to this difference between tegenover and voor is that the relation expressed by tegenover is one of equivalence, in that we can conclude from (226a) that (226a') also holds, and vice versa. The difference between the two cases is mainly one of topichood: the subject is taken to be the topic of the discourse. Equivalence does not apply to the relation expressed by voor: we cannot infer from (226b) that (226b') holds (and vice versa).

| a. | Peter staat | tegenover Jan. ⇔ | |

| Peter stands | oppositie Jan |

| a'. | Jan staat tegenover Peter. |

| b. | Peter staat | voor | Jan. ⇎ | |

| Peter stands | in.front.of | Jan |

| b'. | Jan staat voor Peter. |

Note, however, that there are cases in which the usage conditions of tegenover seem less stringent than in (225a). For instance, example (227a) seems acceptable even though a tree is not usually thought of as an object with a front and a back. One could even use (227b) in a situation where the front of the car is not facing the church.

| a. | De oude kersenboom | staat | tegenover de kerk. | |

| the old cherry tree | stands | opposite the church |

| b. | Mijn auto | staat | tegenover de kerk. | |

| my car | stands | opposite the church |

Perhaps we should conclude from these examples that it is only the orientation of the reference object that ultimately matters, and consider (225a) to be the special case. We leave this open for future research.

As shown in the previous subsection, the interpretation of achter, naast and voor is independent of the dimensional properties of the reference object. This is not true for all prepositions. For example, the preposition langsalong is generally interpreted in terms of the length dimension of the reference object (which is obviously related to the fact that langs is diachronically related to the adjective langlong; cf. etymologiebank.nl/trefwoord/langs). In terms of vectors, we could say that langs denotes a set of vectors that are more or less parallel, i.e. that are all perpendicular to the exterior of the reference object. The examples in (228) show that like achter, naast and voor, the preposition langs can be used to denote either a location or a change of location.

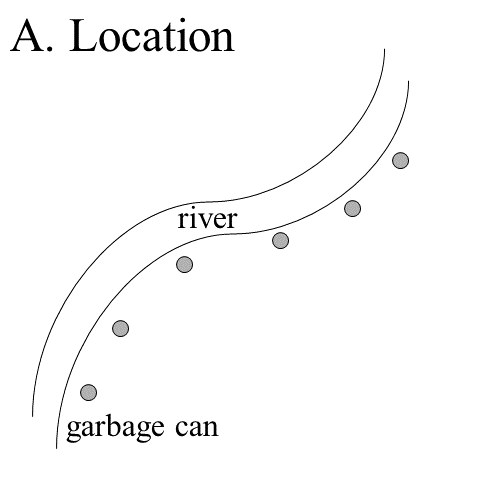

| a. | De vuilnisbakken | staan | langs de rivier. | |

| the garbage.cans | stand | along the river |

| b. | De bewoners | zetten | hun vuilnisbakken | langs de rivier. | |

| the residents | put | their garbage.cans | along the river |

Note, however, that there are also cases in which the importance of the length dimension is reduced, or in which there may be actual contact between the located and reference object (i.e. where the length of the vector is zero); cf. Cuyckens (1995) for a discussion of these different readings of langs. The first case is illustrated by the examples in (229).

| a. | Hij | liep | langs de lantaarnpaal. | |

| he | walked | along the lamppost | ||

| 'He walked past the lamppost.' | ||||

| b. | Jan liep | even | langs | de slager. | |

| Jan walked | prt | along | the butcherʼs | ||

| 'John dropped in at the butcher's.' | |||||

| b. | Jan ging | even | langs oma. | |

| Jan went | prt | along grandma | ||

| 'Jan paid grandma a visit.' | ||||

According to Cuyckens, there are also cases where langs refers to a path that is located on the reference object. One of his examples is given in (230a). It is not clear whether this is a generally accepted structure: we prefer the alternative with over in (230b). That this preference is more general is shown by a Google search (July 11, 2023) for the strings [vervoerd langs de rivieren/het spoor] and [vervoerd over de rivieren/het spoor]: while the first returned no matching results, the second returned 10 hits for de rivieren and 95 hits for het spoor. This contrast is expressed by the percentage sign.

| a. | % | De goederen worden vervoerd langs de rivieren/het spoor. |

| the goods are transported along the rivers/the railroad |

| b. | De goederen worden vervoerd over de rivieren/het spoor. | |

| the goods are transported along the rivers/the railroad | ||

| 'The goods are transported by ship/by rail.' |

Cuyckens’ examples in (231) seem more common, but they do not really involve a path located on the reference object, but seem to express that the located object “closely follows the [reference object] along (one of) its significantly extended dimension(s)” (p.200). This formulation suggests that there is a minimal distance between the path followed by the located object and the reference object, which may not be really different from the core use of langs illustrated in (228).

| a. | De ballonnen zweefden langs het plafond van de kerk. | |

| 'The balloons floated along the ceiling of the church.' |

| b. | De witte wolken dreven langs de hemel/het uitspansel. | |

| 'The white clouds drifted along the sky.' |

| c. | De tranen rolden langs haar wangen. | |

| 'The tears rolled down her cheeks.' |

Fore completeness, note that langs can also be used directionally; this will be discussed in Section 32.3.1.3, sub II, example (271)

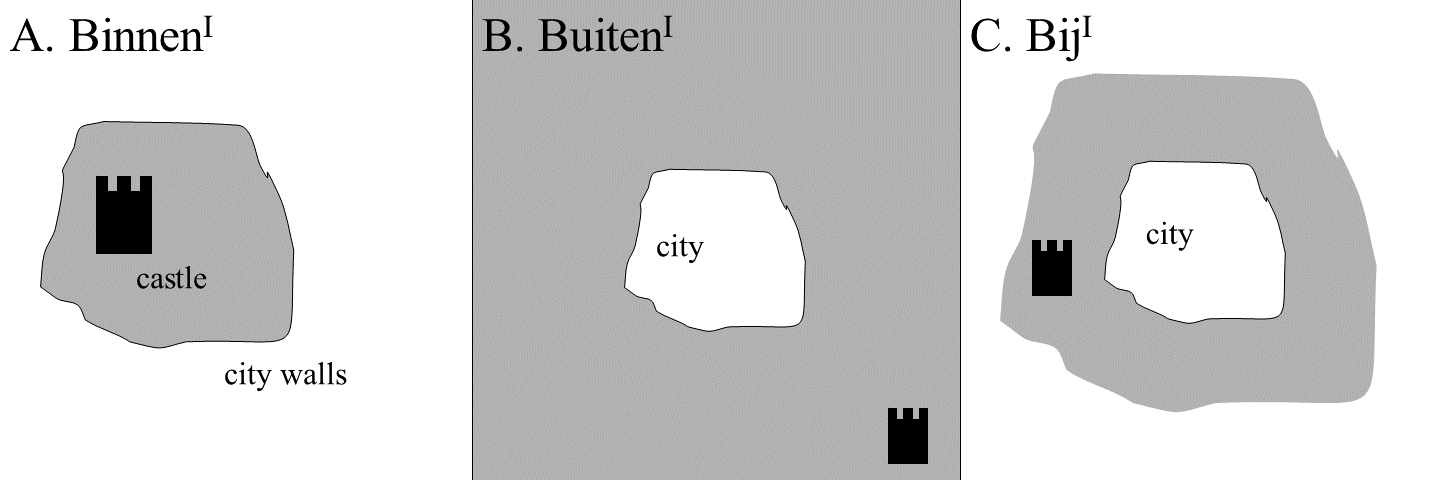

Other prepositions, with an interpretation depending on the physical properties of their reference object, are binneninside/within, buitenoutside and bijnear, which Zwarts (1997b) calls topological prepositions. They require that the reference object divides space into an inner and an outer area. A PP headed by binnen indicates that the located object has a position in the inner area of the reference object, whereas a PP headed by buiten locates it in the outer area. In this respect, bij is the same as buiten, but it has the additional requirement that the position is in the vicinity of the reference object (where the meaning of “in the vicinity” is contextually determined). In Figure 21, the PPs in (232) denote a position within the gray area.

| a. | Het kasteel | staat | binnen | de stadswallen. | |

| the castle | stands | inside | the city walls | ||

| 'The castle is within the city walls.' | |||||

| b. | Het kasteel | staat | buiten | de stadswallen. | |

| the castle | stands | outside | the city walls |

| c. | Het kasteel | staat | bij | de stadswallen. | |

| the castle | stands | near | the city walls |

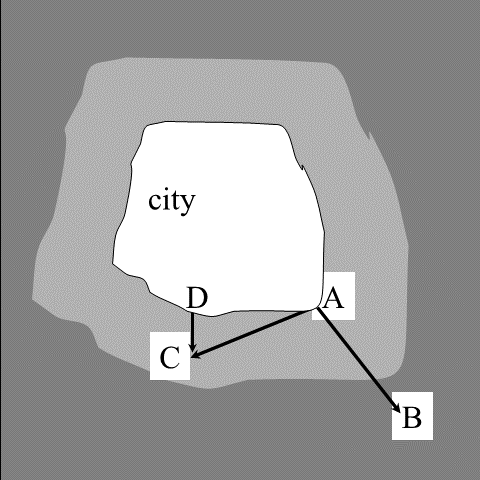

To conclude the discussion of this group of prepositions, it should be noted that it is not easy to fill in the idea that these prepositions denote a set of vectors. First of all, it is not clear what the starting point of the vectors is. Of course, we could make the idealization that the reference object is a point in space, which the vectors take as their starting point, but this would not help us in the case of binnen. Another possibility would be to assume that the positions in the relevant area are defined in terms of the shortest vectors from the outside of the reference object to the positions in question; cf. Figure 22. This would solve the problem that, despite the fact that the magnitudes of the vectors  and

and  are identical, the location of position B but not position C can be properly described by (233a), and (233b) can be used to describe position C but not position B. This is due to the fact that there is a shorter vector

are identical, the location of position B but not position C can be properly described by (233a), and (233b) can be used to describe position C but not position B. This is due to the fact that there is a shorter vector  from the outside of the reference object, which is part of the denotation of vlak bij, so that position C but not position B can be properly described by (233b).

from the outside of the reference object, which is part of the denotation of vlak bij, so that position C but not position B can be properly described by (233b).

| a. | B/#C | ligt | ver | buiten | de stad. | |

| B/C | lies | far | outside | the city | ||

| 'B/C is far from the city.' | ||||||

| b. | C | ligt | vlak | bij | de stad. | |

| C | lies | close | near | the city | ||

| 'C is close to the city.' | ||||||

However, this solution to the problem does not solve the problem that neither the direction nor the magnitude of the vectors denoted by binneninside can be modified. For this reason, it has been assumed that binnen actually involves the null vector as well. We refer the reader to Subsection B for a discussion of the difference between in/uit and binnen/buiten.

Prepositions denoting the null vector can be divided into two groups: prepositions expressing that (part of) the located object is in the reference object and prepositions that simply imply physical contact between the located and reference objects.

The preposition inin differs from binneninside in that it requires physical contact between the reference object and the located object; in involves a null vector. This is illustrated for the examples in (234) by the images in Figure 23. The preposition binnen in (234a) does not imply any physical contact between Jan and the hedge; Jan just has to be somewhere in the gray area in Figure 23A. The preposition in in (234b), on the other hand, requires physical contact, so that the situation must be as shown in Figure 23B.

| a. | Jan zit | binnen | de haag. | |

| Jan sits | inside | the hedge |

| b. | Jan zit | in | de haag. | |

| Jan sits | in | the hedge |

A caveat is in order, however. Example (234a) can be represented by using only two dimensions. If we are dealing with a three-dimensional object, however, the situation is slightly different. Since it is the preposition in, and not binnen, that is used in the examples in (235), we conclude that the inside of a three-dimensional object is mentally construed as a part of the reference object, rather than as its inner area.

| a. | De vogel | zit in/*binnen | de kooi. | |

| the bird | sits in/inside | the cage | ||

| 'The bird is in the cage.' | ||||

| b. | Jan is in/*binnen | zijn kamer. | |

| Jan is in/inside | his room | ||

| 'Jan is in his room.' | |||

Like in but unlike buitenoutside, uitout of implies that there is some physical contact with the reference object. For this reason, buiten (but not uit) can be used to refer to the situation in Figure 24A. In fact, example (236b) shows that uit cannot be used at all; if there is physical contact with the reference object, in takes precedence over uit; cf. Jan zit in de haag.

| a. | Jan zit | buiten | de haag. | |

| Jan sits | outside | the hedge |

| b. | * | Jan zit | uit | de haag. |

| Jan sits | out.of | the hedge |

Buiten also seems to be preferred in the case of three-dimensional objects, although uit can sometimes also be used. It is not clear to us under what conditions uit can or cannot be used with three-dimensional objects.

| a. | De vogel | zit | buiten/*uit | zijn kooi. | |

| the bird | sits | outside/out.of | his cage | ||

| 'The bird is outside its cage.' | |||||

| b. | De vogel | is | ?buiten/uit | zijn kooi. | |

| the bird | is | outside/out.of | his cage | ||

| 'The bird is out of its cage.' | |||||

| c. | De pen | ligt buiten/uit | zijn doos. | |

| the pencil | lies outside/out.of | his box | ||

| 'The pencil is out of its box.' | ||||

The discussion above shows that the preposition buiten is usually preferred to uit with (static) location verbs. However, example (238b) shows that the preposition uit is possible with change-of-location verbs such as halento get, whereas buiten is not allowed in this context. This seems to be due to the fact that this verb expresses that the contact between the located and the reference object is broken; this would be consistent with the fact, illustrated in (238a), that the antonym of halen, stoppento put, only allows in.

| a. | Jan stopt | de vogel | in/*binnen | de haag. | |

| Jan puts | the bird | in/inside | the hedge |

| b. | Jan haalt | de vogel | uit/*buiten | de haag. | |

| Jan gets | the bird | out.of/outside | the hedge |

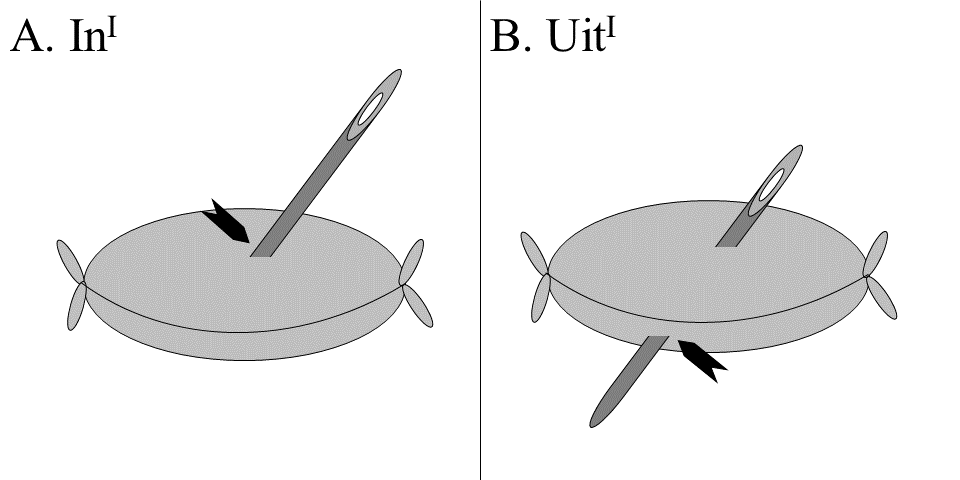

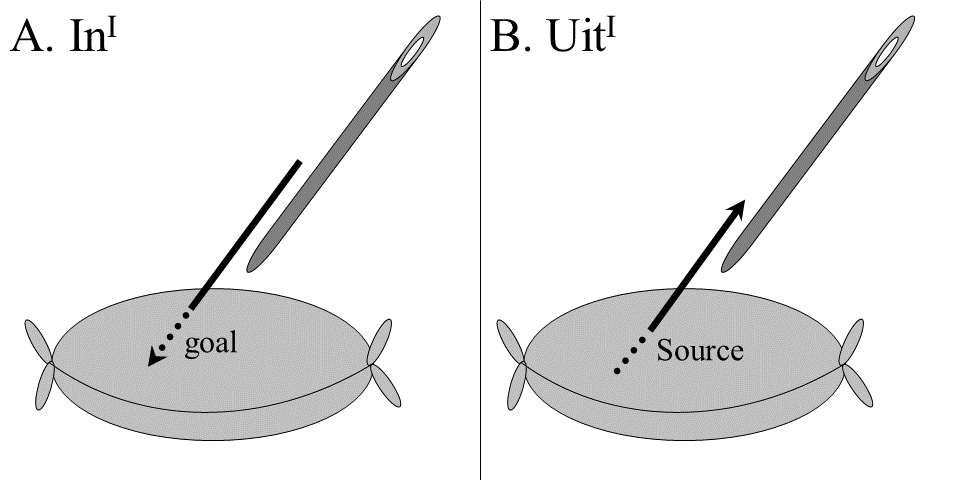

The prepositions in and uit imply physical contact between the located object and the reference object at some point in time. However, the preposition in does not imply that the located object is completely physically enclosed by the reference object; this may only be partially the case. Similarly, the preposition uit implies that only a part of the located object protrudes from the reference object. This is illustrated by the examples in (239); the arrows in Figure 25 indicate the points that are relevant to the interpretation of the examples in (239).

| a. | De naald | zit | in het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sits | in the pincushion | ||

| 'The needle sticks in the pincushion.' | ||||

| b. | De naald | steekt | uit | het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sticks | out.of | the pincushion | ||

| 'The needle sticks out of the pincushion.' | |||||

In and uit differ in that the former is compatible with full inclusion, whereas the latter necessarily implies partial inclusion; this is clear from the fact that the adverbial phrase helemaalcompletely can be used with in, but not with uit (unless we are dealing with exaggeration). Note that, as expected, substituting bijna helemaalnearly completely for helemaal in (239b) would produce a fully acceptable result. The modifier een klein stukjea small piece expresses that the encompassment is not complete and is possible with both PPs, as expected.

| a. | De naald | zit | helemaal/een klein stukje | in het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sits | completely/a small piece | in the pincushion | ||

| 'The needle sticks completely/partly in the pincushion.' | |||||

| b. | De naald | steekt | ??helemaal/een klein stukje | uit | het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sticks | completely/a small piece | out.of | the pincushion | ||

| 'The needle sticks partly out of the pincushion.' | ||||||

The examples in (238) have already shown that in and uit can also be used to denote a change of location; cf. Figure 26. Some more examples are given in (241): in (241a) the reference object refers to the new position of the located object, and in (241b) it refers to its original position. In this case, the adverbial phrase helemaalcompletely can easily be used with both PPs; helemaal in (241b) expresses that the contact between the located and the reference object is completely broken.

| a. | Jan steekt | de naald | (helemaal/een klein stukje) | in | het speldenkussen. | |

| Jan sticks | the needle | completely/a small piece | into | the pincushion | ||

| 'Jan sticks | ||||||

| the needle (completely/partly) into the pincushion.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan haalt | de naald | (helemaal/een klein stukje) | uit | het speldenkussen. | |

| Jan gets | the needle | completely/a small piece | out.of | the pincushion | ||

| 'Jan gets the needle (completely/partly) out of the pincushion.' | ||||||

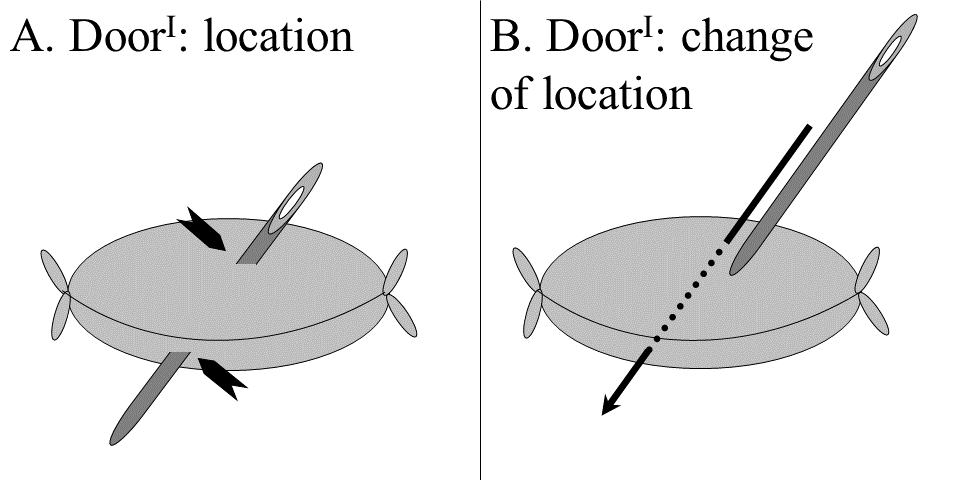

In a sense, the preposition door combines the meanings of in and uit. In (242a), the PP door het speldenkussen expresses that the located object sticks both in and out of the reference object; in other words, both points indicated by the arrows in Figure 27A are relevant. In (242b), the PP indicates that the located object ends up in the position in Figure 27A as a result of Janʼs action; this is shown in Figure 27B.

| a. | De naald | steekt | door | het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sticks | through | the pincushion |

| b. | Jan steekt | de naald | door | het speldenkussen. | |

| Jan sticks | the needle | through | the pincushion | ||

| 'Jan pushes the needle through the pincushion.' | |||||

The prepositions in and uit seem to differ from the preposition door in that the former can only be used in constructions involving a (change of) location, whereas the latter can also occur in directional constructions. This is clear from the fact that the examples in (243) with the verb of traversing rijdento drive are at best marginal with in and uit, but perfectly acceptable with door; cf. Section 32.1.2, sub II. The primed examples are added to show that all three adpositions can be used to express directional meanings when they are used as postpositions.

| a. | ?? | De auto | is in/uit | de autowasserette | gereden. |

| the car | is into/out.of | the car wash | driven | ||

| 'The car has driven into/out of the car wash.' | |||||

| a'. | De auto is de autowasserette in/uit gereden. |

| b. | De auto | is door | de autowasserette | gereden. | |

| the car | is through | the car wash | driven | ||

| 'The car has driven through the car wash.' | |||||

| b'. | De auto is de autowasserette door gereden. |

However, there is a slight difference in meaning between (243b) and (243b') that is hard to pinpoint. Perhaps another example may clarify this. If Jan drives through a meadow from one from one side to the other, door will be appear as a preposition, not as a postposition. This is shown in the (a)-examples in (244); the acceptability contrast becomes even clearer when the reference object is relatively small, like a puddle of rainwater. However, if Jan drives right through a forest from one end to the other, it is also possible to use door as a postposition, as shown in (244b'). This suggests that in order to use door as a postposition, the located object must be completely surrounded by the reference object (i.e. in all three dimensions), whereas this is not necessary when it is used as a preposition. We leave this to future research.

| a. | Jan is door het weiland/de regenplas | gereden. | |

| Jan is through the meadow/puddle | driven | ||

| 'Jan has driven through the meadow/puddle.' | |||

| a'. | # | Jan is het weiland/de regenplas door gereden. |

| b. | Jan is door het bos | gereden. | |

| Jan is through the forest | driven | ||

| 'Jan has driven through the forest.' | |||

| b'. | Jan is het bos door gereden. |

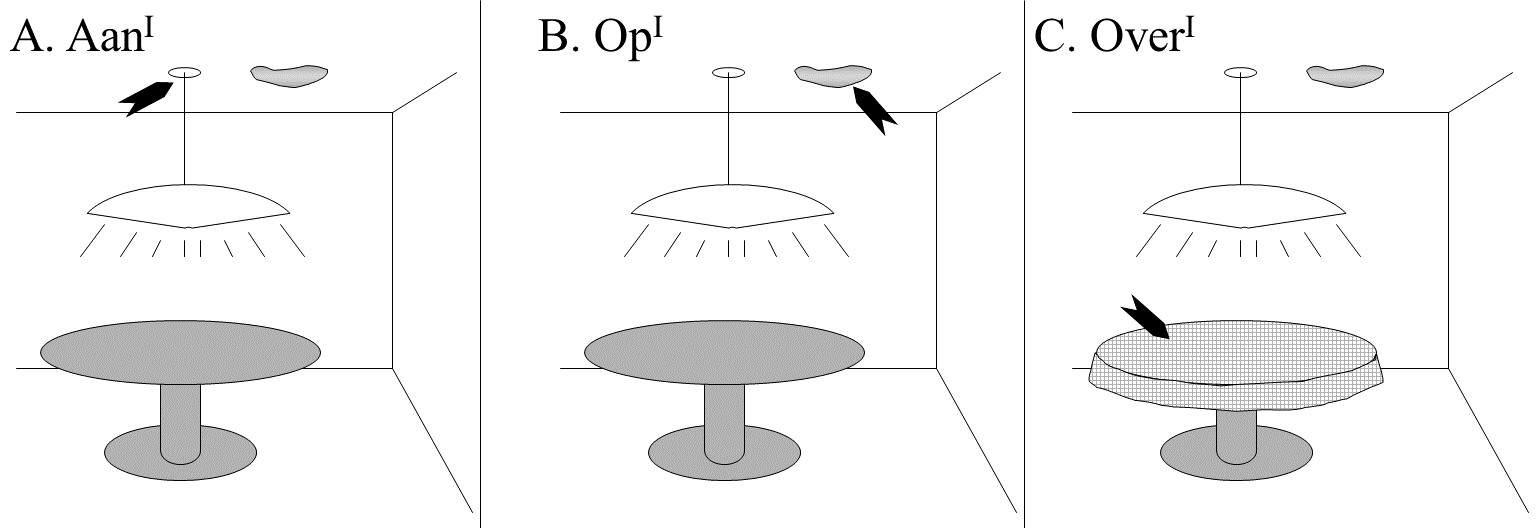

Whereas in, uit and door imply that the located object is at least partly located in the reference object, the prepositions aan, op, over and tegen in (245) merely require that there should be some contact between the two.

| a. | Er | hangt | een lamp | aan het plafond. | |

| there | hangs | a lamp | on the ceiling | ||

| 'A lamp hangs from the ceiling.' | |||||

| b. | Er | zit | een vlek | op het plafond. | |

| there | sits is | a stain | on the ceiling | ||

| 'There is a stain on the ceiling.' | |||||

| c. | Er | ligt | een kleed | over de tafel. | |

| there | lies | a rug | over the table | ||

| 'There is a rug on the table.' | |||||

| d. | Er | staat | een ladder | tegen de muur. | |

| there | stands | a ladder | against the wall | ||

| 'There is a ladder against the wall.' | |||||

The four prepositions differ with respect to the kind of contact they imply. The preposition aan is compatible with minimal contact: the lamp in (245a) is connected to the ceiling only by its wire. The preposition op suggests more extended contact between the located object and the reference object; the stain in (245b), of course, has maximum contact with the ceiling. The preposition over also suggests more extended contact, but now it is the reference object that has more extended contact with the located object.

In (245), the PPs headed by aan, op, over are used with a location verb; however, the examples in (246) show that they can also be used with the causative counterparts of these verbs indicating a change of location.

| a. | Jan hangt | een lamp | aan het plafond. | |

| Jan hangs | a lamp | on the ceiling |

| b. | Jan zet | een lamp | op de tafel. | |

| Jan puts | a lamp | on the table |

| c. | Jan legt | een kleed | over de tafel. | |

| Jan puts | a cloth | over the table |

| d. | Jan zet | een ladder | tegen de muur. | |

| Jan puts | a ladder | against the wall |

The examples in (245) deserve further discussion. It has been claimed that the preposition aan expresses minimal distance, not minimal contact. Examples supporting this are provided in (247): they do not imply physical contact between the ship and the quay, or the house and the lake. If minimal distance is the correct characterization, aan must be assumed to denote a set of vectors which are smaller than some contextually determined size, just like bijnear shown in (232); aan and bij differ, however, in that only aan seems compatible with actual physical contact.

| a. | Het schip | ligt | aan de kade. | |

| the ship | lies | on the quay | ||

| 'The ship is tied up to the quay.' | ||||

| b. | Het huis | staat | aan het meer. | |

| the house | stands | on the lake | ||

| 'The house stands near the lake.' | ||||

The examples in (245b&c) and (246b&c) may suggest that op and over imply some notion of full contact of the located object with the reference object or vice versa. This is not always the case, as the examples in (248) make clear; (248a) suggests that only the bottom of the lamp is in contact with the table (cf. Figure 7A) and (248b) is compatible with a situation in which the chair is only partly covered by the coat. This use is again not restricted to location verbs but can also be used with the change-of-location verbs in the primed examples.

| a. | De lamp | staat | op de tafel. | |

| the lamp | stands | on the table |

| a. | Jan zet | de lamp | op de tafel. | |

| Jan puts | the lamp | on the table |

| b. | De jas | hangt | over de stoel. | |

| the coat | hangs | over the chair |

| b'. | Jan hangt de jas over de stoel | |

| Jan hangs the coat over the chair |

The difference between op and over seems to be that the locational relation is more point-like in the case of op and more area-like in the case of over. The adverbial phrase kriskras in (249a) implies that the path traversed by the player covers an extended area of the field, leading to a clear preference for the use of over. Similarly, the verb verspreiden implies that the end positions of the players are spread over a larger area of the field, and again over is the preferred option. Note that op in (249a) is possible without the adverbial phrase kriskras; it is then simply used to indicate where the action of running takes place; cf. Geeraerts (2023) for a detailed discussion of the role of the notion of area in the semantic structure of over.

| a. | De speler | rent kriskras | over/?op het veld. | |

| the player | runs crisscross | over/on the field |

| b. | De spelers | verspreiden | zich | over/?op het veld. | |

| the players | spread | refl | over/on the field |

The meaning of the preposition tegenagainst is difficult to characterize. It is often used in the sense of “touching the side surface of the reference object”, as in (245d), but resultative constructions such as (250) are also possible.

| a. | Jan gooide | een pannenkoek | tegen het plafond. | |

| Jan threw | a pancake | against the ceiling |

| b. | Jan sloeg | Peter tegen de grond. | |

| Jan hit | Peter against the floor |

These examples suggest that tegen means (or can mean) something like “touching the reference object while exerting force on it”, which would fit in well with the non-locational uses of tegen in examples such as (251).

| a. | Jan zwom | tegen | de stroom. | |

| Jan swam | against | the current |

| b. | Marie protesteerde | met kracht | tegen | dat besluit. | |

| Marie protested | with force | against | that decision |

| c. | Marie vocht | hard tegen | een ernstige griep. | |

| Marie fought | hard against | a serious flu |

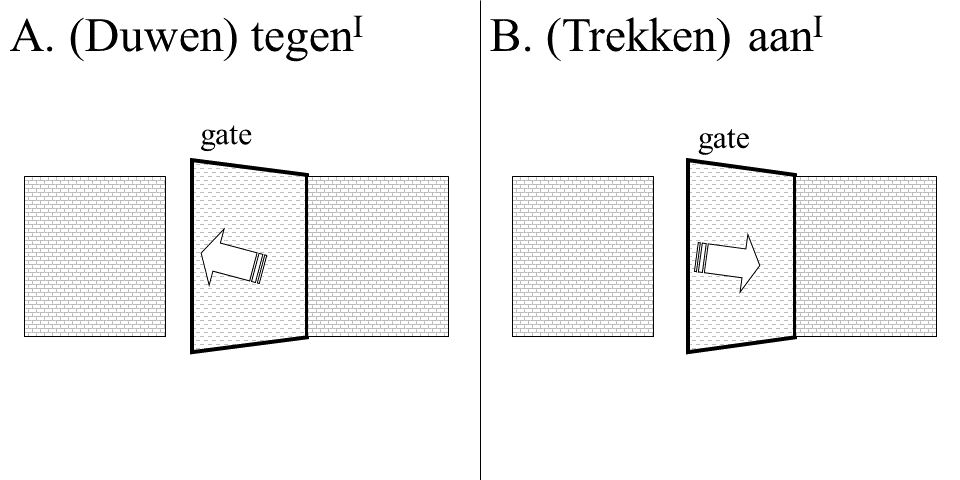

If the notion of exerting force is indeed appropriate in characterizing the preposition tegen, it may be the case that tegen and aan act as antonyms with respect to the direction of the exerted force (at least in some cases). The examples in (252) may make this clear. The verbs duwento push and trekkento pull both express that a force is exerted on the complement of the (non-spatial) prepositional complement of the verb: in the first case the force is directed towards it, and only the preposition tegen can be used, but in the second case the direction of the force is reversed, and only the preposition aan is possible. This is illustrated in Figure 29, where the arrow indicates the direction of the force exerted by Jan.

| a. | Jan | duwde | tegen/*aan | het hek. | |

| Jan | pushed | against/on | the gate |

| b. | Jan | trok | aan/*tegen | het hek. | |

| Jan | pulled | on/against | the gate |

The previous subsections discussed three main classes of spatial prepositions: deictic, absolute and inherent prepositions. Our results are summarized in Table 17 below. The class of deictic prepositions is rather small and can also be used inherently; they are strictly locational, i.e. they cannot be directional. The class of absolute prepositions can be divided into two subclasses: the first is locational (and possibly also directional) in nature, while the second is strictly directional. The inherent prepositions can also be divided into two main groups: those that denote a set of vectors (type I) and those that denote the null vector (type II). Type I can be further divided into prepositions that are similar to deictic prepositions in that they refer to the dimensions mentally attributed to the reference object (type Ia), and prepositions referring to the physical dimensions of the reference object (type Ib). Type II can be further subdivided into prepositions that require the located object to be inside the reference object (type IIa) and prepositions that require only some contact between the located object and the reference object (type IIb). We added the formal preposition te (not discussed above) because it is only used in locational constructions such as Jan woont te AmsterdamJan lives in Amsterdam, whereas all other locational prepositions can be used in constructions involving a location or a change of location. Finally, it can be observed that the prepositions can be divided into two main groups, depending on whether the preposition involves the orientation/direction of the vectors it denotes, or their magnitude, i.e. the distance between the located and the reference object. The first group includes all deictic and directional prepositions; the second group, for obvious reasons, includes all prepositions denoting the null vector.

| type | preposition | deictic | inherent | absolute | locational | directional | vector | ||

| null | orient/dir | magnitude | |||||||

| Deictic | achter ‘behind’ | + | + | — | + | — | — | + | — |

| naast ‘next to’ | + | + | — | + | — | — | + | — | |

| voor ‘in front of’ | + | + | — | + | — | — | + | — | |

| AbsoluteType I | boven ‘above’ | — | — | + | + | — | — | + | — |

| om ‘around’ | — | — | + | + | ? | — | + | — | |

| onder ‘under’ | — | — | + | + | ? | — | + | — | |

| rond ‘around’ | — | — | + | + | ? | — | + | — | |

| tussen ‘between’ | — | — | + | + | ? | — | + | — | |

| AbsoluteType II | naar ‘to’ | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | — |

| over (I) ‘over/across’ | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | — | |

| tot (en met) ‘until’ | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | — | |

| van ‘from’ | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | — | |

| vanaf ‘from’ | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | — | |

| vanuit ‘from out of’ | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | — | |

| via ‘via’ | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | — | |

| voorbij ‘past’ | — | — | + | — | + | — | + | — | |

| InherentType Ia | tegenover ‘opposite’ | — | — | + | + | — | — | + | — |

| achter, naast, voor | — | — | + | + | — | — | + | — | |

| InherentType Ib | binnen ‘inside’ | — | — | + | + | — | ? | — | + |

| buiten ‘outside’ | — | — | + | + | — | — | — | + | |

| bij ‘near’ | — | — | + | + | — | — | — | + | |

| langs ‘along’ | — | — | + | + | ? | — | — | + | |

| InherentType IIa | in ‘in’ | — | — | + | + | — | + | — | + |

| uit ‘out of’ | — | — | + | + | — | + | — | + | |

| door ‘through’ | — | — | + | + | + | + | — | + | |

| InherentType IIb | aan ‘on’ | — | — | + | + | — | + | — | + |

| op ‘on’ | — | — | + | + | — | + | — | + | |

| over (II) ‘over’ | — | — | + | + | — | + | — | + | |

| tegen ‘against’ | — | — | + | + | — | + | — | + | |

| te | te ‘in/at’ | — | + | — | + | — | + | — | + |

This section has focused mainly on cases in which the spatial PP is used as a complementive and is thus predicated of some nominal argument of the clause. It should be noted, however, that if the PP is used adverbially, the preposition can also be considered as a two-place predicate; the only difference is that the located entity is now no longer expressed by a nominal argument, but by a verbal projection. In (253) the preposition in establishes a spatial relation between the eventuality of Marie and Jan playing soccer and the garden; the eventuality e takes place in the garden, as indicated in (253b).

| a. | Marie en Jan | voetballen | in de tuin. | |

| Marie and Jan | play.soccer | in the garden | ||

| 'Marie and Jan are playing soccer in the garden.' | ||||

| b. | IN (e, the garden) |