- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

The vast majority of temporal adpositional phrases are prepositional in nature, although postpositions and circumpositions are sometimes used. Verbal particles are not used to express temporal relationships. The following subsections discuss the three types of adpositional phrases that can be found.

This subsection focuses on the semantics of temporal prepositions. After a more general discussion, we will look at the individual prepositions in more detail.

Table 25 lists the subset of prepositions used productively with a temporal meaning: they are characterized by the fact that they can take any nominal complement referring to an entity occupying a fixed position/interval on the timeline.

| preposition | example | translation |

| gedurende | gedurende de voorstelling | during the performance |

| na | na de les | after the lesson |

| sinds | sinds de laatste vergadering | since the last meeting |

| tijdens | tijdens de les | during the lesson |

| tot (en met) | tot (en met) mijn vakantie | up to and including my vacation |

| tussen | tussen kerst en Nieuwjaar | between Christmas and New Year |

| vanaf | vanaf mijn vakantie | from my vacation |

| voor | voor mijn vakantie (also: tien voor vijf) | before my vacation ten (minutes) to five (4.50 h) |

The preposition sindssince has the more formal Dutch equivalent sedert. The preposition vanaf can be replaced by the latinate preposition per, followed by a date: vanaf/per 23 februarifrom February 23.

The prepositions in Table 26 differ from those in Table 25 in that they impose more specific selection restrictions on their complements; they require a complement that refers to a specific time, date, or well-defined period of time (such as a segment of the day, holidays such as Easter and Christmas, and so on). Although the list of possible complements in the fourth column of Table 26 is not exhaustive, it should give an inkling of the restrictions imposed on the complements. The prepositional phrases preceded by a number sign are possible but cannot be used with a temporal meaning, so we refrain from giving a translation of the prepositions involved.

| example | translation | possible complements | |

| in | in de ochtend | during the morning | segments of the day, months, seasons, years |

| #in de voorstelling | — the performance | ||

| met | met kerstmis | during Christmas | holidays, seasons (except lente ‘spring’) |

| #met de les | — the lesson | ||

| om | om tien over drie | at ten past three | times of the day |

| #om de vakantie | — the vacation | ||

| omstreeks | omstreeks kerstmis | around Christmas | holidays, dates, months, seasons, years |

| *omstreeks de les | — the lesson | ||

| op | op kerstavond | on Christmas eve | parts of holidays, dates |

| #op de vergadering | — the meeting | ||

| rond | rond kerstmis | around Christmas | holidays, dates |

| #rond de voorstelling | — the performance | ||

| tegen | tegen kerstmis | towards Christmas | holidays, times, dates, months, seasons |

| #tegen de les | — the lesson | ||

| van | van de week | during last/next week | seasons, week ‘week’, weekend ‘weekend’ |

| #van de les | — the lesson |

Note in passing that, as an alternative to (358a), it is possible to use example (358b). In this use, the complement of the preposition bij must be a numeral followed by the affix -en. The preposition naar in (358c) is similar to bij in this respect. The examples in (358) all express that it is nearly 9 o'clock.

| a. | Het | loopt | al | tegen | negen uur. | |

| it | walks | already | towards | nine o'clock | ||

| 'We are approaching (the time of) nine o'clock.' | ||||||

| b. | Het | is | al | bij | negenen. | |

| it | runs/is | already | close.to | nine o'clock | ||

| 'It is almost nine o'clock.' | ||||||

| c. | Het | loopt | al | naar | negenen. | |

| it | walks | already | towards | nine o'clock | ||

| 'We are gradually approaching (the time of) nine o'clock.' | ||||||

This “approximation” meaning of tegen is even more salient in (359), where it is used as a kind of adverbial modifier: the phrase tegen de twee uur seems to be more or less synonymous with ongeveer twee uur. More discussion of the approximative use of prepositions can be found in Section .

| a. | Het examen | duurt | tegen de | twee uur. |

| b. | Het examen | duurt | ongeveer twee uur. | |

| the exam | lasts | approximately two hours |

Another special case worth mentioning is (360a). The PP met de dag does not refer to a specific time on the timeline, but rather functions like a frequency adverb like elke dagevery day. However, it differs from the regular frequency adverbs in that it only occurs in accumulative constructions such as (360a).

| a. | Het | wordt | met de dag/elke dag | warmer. | |

| it | becomes | with the day/every day | hotter | ||

| 'It is getting hotter every day.' | |||||

| b. | Jan komt | hier | elke dag/*met de dag. | |

| Jan comes | here | every day/with the day |

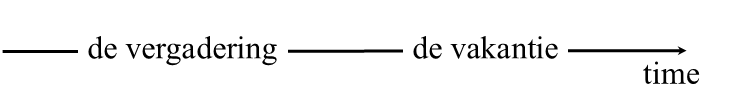

From a semantic point of view temporal prepositions are two-place predicates that establish a temporal relation between their two arguments: the referents of these arguments are situated on the timeline in positions relative to each other. In (361a), for example, the temporal PP voor de vakantiebefore the vacation places the subject of the clause de vergaderingthe meeting at a position on the timeline preceding the position of the complement of voor, de vakantiethe vacation; this can be represented by the logical formula in (361b) or the graph in (361c).

| a. | De vergadering | is nog | voor de vakantie. | |

| the meeting | is prt | before the vacation |

| c. | voor (de vergadering, de vakantie) |

| b. |  |

If we consider the timeline as a representation of “temporal space”, we can call de vergadering the located object and de vakantie the reference object, just as in the case of spatial prepositions. However, since the interpretation of the temporal prepositions in Table 25 is largely determined by the properties of the one-dimensional timeline, it does not seem useful to make a distinction between inherent and absolute interpretations, since this distinction can only be made by appealing to at least two dimensions. This leaves us with the question of whether there are temporal PPs with a deictic interpretation. Some possible cases of such deictic PPs are given in Table 27. However, we will show that there are reasons for assuming that these PPs are not temporal in nature.

| preposition | example | translation |

| binnen | binnen tien minuten | within an hour |

| in | in tien minuten | (with)in ten minutes |

| over | over tien minuten (also: tien over vijf) | in ten minutes ten (minutes) past five (5.10 h) |

| om | om de week (lit.: around the week) | once every two weeks |

In the examples in (362), the PPs denote a time span of ten minutes calculated from the speech time. This means that the complement of the preposition does not act as the reference point from which the position of the located object is calculated. In fact, the complements of the prepositions do not occupy any place on the timeline at all, and are therefore not even suitable to act as a reference point.

| a. | Ik | ben | binnen tien minuten | bij je. | |

| I | am | within ten minutes | with you | ||

| 'I will be with you in ten minutes (from now).' | |||||

| b. | Ik | ben | in tien minuten | bij je. | |

| I | am | in ten minutes | with you | ||

| 'I will be with you (with)in ten minutes (from now).' | |||||

| c. | Ik | ben | over tien minuten | bij je. | |

| I | am | in ten minutes | with you | ||

| 'I will be with you in ten minutes (from now).' | |||||

The fact that the complement of the preposition does not seem to play a role in the computation of the temporal location of the located object casts serious doubt on any claim that we are dealing with temporal prepositional phrases. Instead, the PPs in (362) seem to play a role similar to that of the manner adverb snelsoon or the adverbial element zo in (363).

| Ik | ben snel/zo | bij je. | ||

| I | am soon/in.a.moment | with you |

Thinking of the PPs in (362) as adverbial modifiers may also account for the fact that they can be used as modifiers of temporal adpositional phrases; for example, the PP binnen tien minuten in (364a) has a function similar to that of the adjectival modifier kortshortly in (364b).

| a. | Het slachtoffer | overleed | binnen tien minuten | na het ongeluk. | |

| the victim | died | within ten minutes | after the accident |

| b. | Het slachtoffer | overleed | kort | na het ongeluk. | |

| the victim | died | shortly | after the accident |

The PP headed by om in (365a) does not seem to function as a temporal PP either. Instead, it seems to function as an adverbial phrase of frequency, comparable to adjectives like regelmatigregularly or wekelijksweekly in (365b). This usage is discussed in more detail in Section .

| a. | Jan komt | hier | om de week. | |

| Jan comes | here | om the week | ||

| 'Jan comes here every second week.' | ||||

| b. | Jan komt | hier | regelmatig/wekelijks. | |

| Jan comes | here | regularly/weekly | ||

| 'Jan comes here regularly/weekly.' | ||||

We conclude that the prepositional phrases in Table 27 are not temporal in nature.

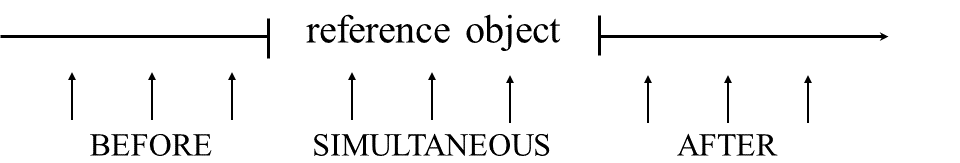

The discussion of (361) has indicated that the semantics of temporal and spatial adpositional phrases are similar in the sense that they can both be considered as two-place predicates. However, the temporal relations that can be expressed are simpler than the spatial relations, due to the fact that space is three-dimensional, while the timeline is only one-dimensional. An exhaustive description of the spatial relations minimally requires relations like in front of, at, behind, next to, above and below (cf. Figure 14 in Section 32.3.1.2, sub IIA). Temporal relations can be exhaustively described with the three relations before, simultaneous, and after, as in (366); cf. Comrie (1985).

| Timeline |

|

Although spatial and the temporal prepositions can be described in similar ways, there is a conspicuous difference between the two. Spatial PPs are often used both as complementives and as adverbial phrases, whereas temporal PPs are mainly used as adverbial phrases; although the complementive use of temporal PPs does not seem impossible (example (361a) may be a case at hand), this use is rare. This difference in usage is probably related to the ontological nature of the entities involved. Whereas spatial adpositional phrases locate objects or events in space, temporal adpositional phrases locate events on the timeline. Since objects are typically denoted by noun phrases and events by verbal projections, spatial adpositional phrases can be predicated of both noun phrases and verbal projections, whereas temporal adpositional phrases are typically predicated of verbal projections. With this in mind, we can continue to discuss the temporal relations depicted in (366) in more detail.

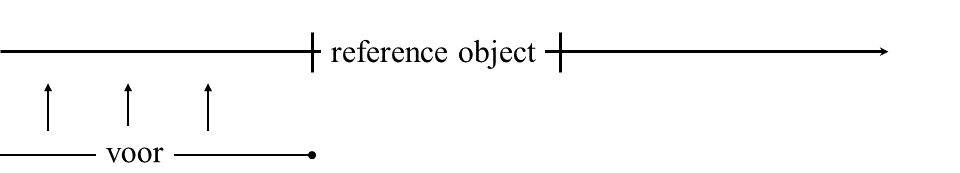

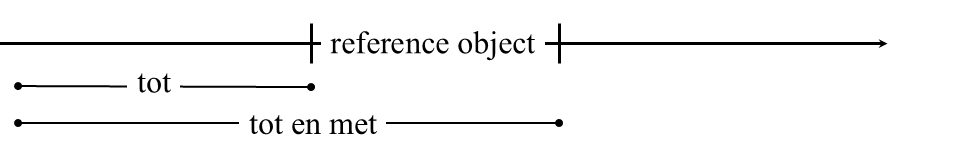

The anteriority re before can be expressed by the prepositions voorbefore and tot (en met)until from Table 25. The two differ in that voor refers to some specific point(s) on the timeline that precedes the position of the reference object, whereas tot (en met) refers to an interval beginning at some point before the position of the reference object and extending until the position of the reference point is reached. The difference between tot and tot en met is that the interval denoted by tot does not include the position of the reference object, while the interval denoted by tot en met does.

| a. | Timeline: voor ‘before’ |

|

| b. | Timeline: tot (en met) ‘until’ |

|

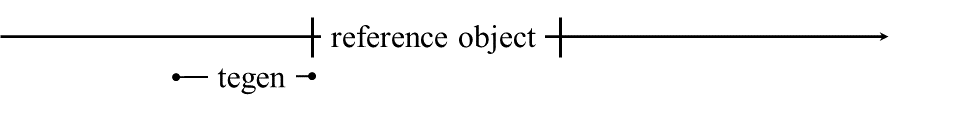

The preposition tegentowards from Table 26 denotes a point or an interval preceding the reference object; in addition it expresses some notion of proximity, in that the located object must be situated close to the reference object.

| Timeline: tegen ‘towards’ |

|

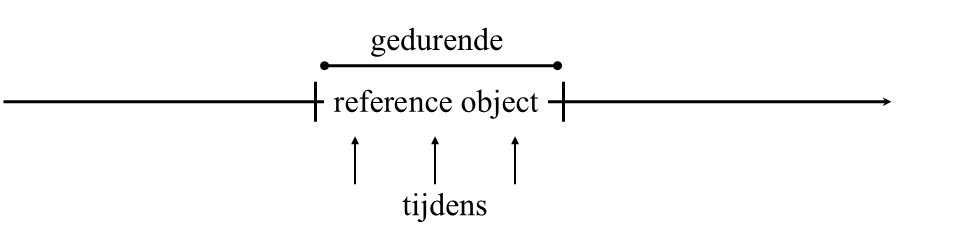

The notion of Simultaneity can be expressed by the prepositions tijdensduring and gedurendeduring from Table 25. Although intuitions are not as clear as in the case of voor and tot (en met), the two prepositions seem to differ in the same way: tijdens preferably refers to some specific point(s) on the timeline occupied by the reference object, whereas gedurende refers to an interval included in the interval occupied by the reference object.

| Timeline: tijdens ‘during’ and gedurende ‘during’ |

|

The prepositions in, met, and op from Table 26 also denote a point or an interval included in the interval occupied by the reference object. The preposition om is special in that it does not refer to some point(s) or an interval, but to one specific position; this is probably due to the fact that the reference object refers to a specific time, as in om tien over drieat ten past three.

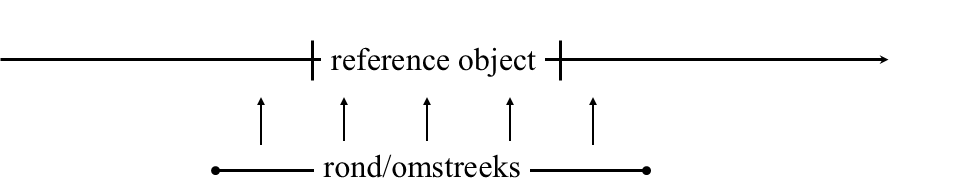

The prepositions omstreeksaround and rondaround from Table 26 differ from the prepositions discussed above in that the located object does not have to be placed within the time interval that is covered by the reference object; however, as is also the case with tegentowards, a notion of proximity is involved: the located object must at least be situated close to the reference object, which itself may but need not be included.

| Timeline: omstreeks ‘around’ and rond ‘around’ |

|

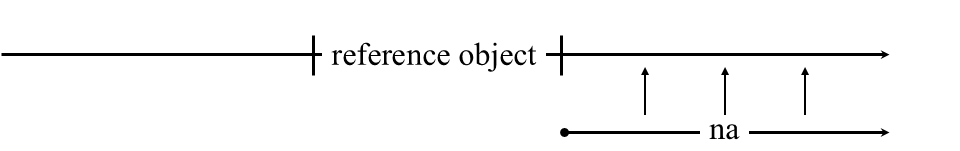

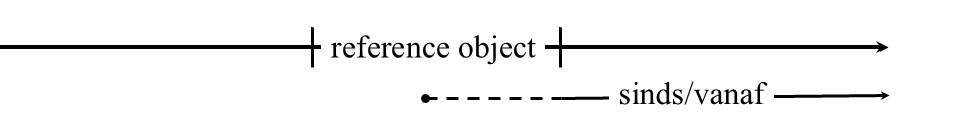

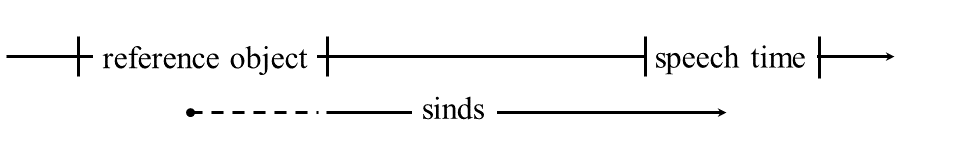

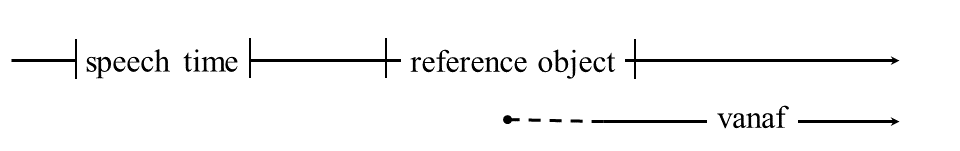

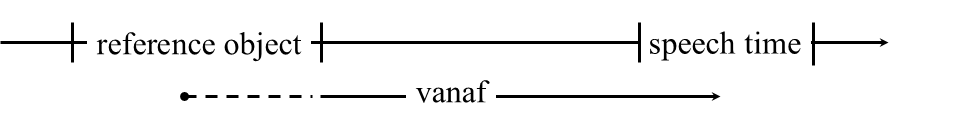

The posteriority relation after can be expressed by the prepositions naafter, sindssince and vanaf(starting) from in Table 25. The prepositions differ in the same way as voor and tot (en met): na refers to some specific point(s) on the timeline following the position of the reference object; sinds and vanaf refer to an interval on the timeline starting at or immediately after the position of the reference object.

| a. | Timeline: na ‘after’ |

|

| b. | Timeline: sinds ‘since’ and vanaf ‘from’ |

|

The difference between sinds and vanaf seems to be related to the position of the speech time. In the case of sinds, the position of the reference object must precede the speech time, as in (372a), whereas in the case of vanaf the position of the reference object preferably follows the speech time, as in (372b).

| a. | dat | Jan sinds/??vanaf | gisteren | niet meer | rookt. | |

| that | Jan since/ from | yesterday | no longer | smokes |

| a'. |  |

| b. | dat | Jan vanaf/*sinds | morgen | niet meer | zal | roken. | |

| that | Jan from/since | tomorrow | no longer | will | smoke |

| b'. |  |

Occasionally, however, vanaf can also be used to refer to the situation depicted in (373b), but this requires a special syntactic context, such as the perfect tense in (373a), or an adverb like alalready in (373a').

| a. | dat | Jan sinds/vanaf | gisteren | niet meer | heeft | gerookt. | |

| that | Jan since/since | yesterday | no longer | has | smoked |

| a'. | dat | Jan al | sinds/vanaf | gisteren | niet meer | rookt. | |

| that | Jan already | since/since | yesterday | no longer | smokes |

| b. |  |

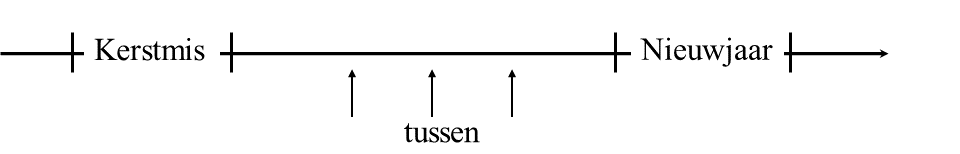

Like its spatial counterpart, the temporal preposition tussen usually requires a plural complement (often in a coordinated structure). The position of the located object on the timeline is calculated on the basis of two reference objects, as in (374).

| a. | tussen | Kerstmis | *(en | Nieuwjaar) | |

| between | Christmas | and | New Year |

| b. |  |

The set of temporal postpositions is even smaller than the set of spatial postpositions: it is limited to ininto, uitout of and doorthroughout. The use of these postpositions is also quite limited. The temporal postposition in indicates that the endpoint of the implied (temporal) path is situated within the interval on the timeline occupied by the reference object. The reference object usually refers to a conventional time unit, such as weekweek, maandmonth, jaaryear, etc., preceded by the attributive adjective nieuwnew, as in (375a). The temporal postposition uit probably indicates that the starting point is located within the interval on the timeline occupied by the reference object, but this is difficult to figure out, because it is only used in the more or less fixed expression ... in ... uit, where the dots indicate a noun phrase like dagday, week, maandmonth, jaaryear, etc.

| a. | We | gaan | volgende week | het nieuwe jaar | in. | |

| we | go | next week | the new year | into | ||

| 'Next week, the new year will begin.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan doet dag in | dag uit | hetzelfde werk. | |

| Jan does day into | day out.of | the.same work | ||

| 'Jan does the same kind of work, day in day out.' | ||||

The postposition door does not impose similar restrictions on its complement: any noun phrase referring to an entity that occupies an interval on the timeline is possible. It seems, however, that the quantifier heel is obligatory.

| a. | Jan was zijn hele vakantie | door | ziek. | |

| Jan was his complete vacation | through | ill | ||

| 'Throughout his vacation, Jan was ill.' | ||||

| b. | Jan zeurde | de hele vergadering | door | over zijn baas. | |

| Jan nagged | the complete meeting | through | about his boss | ||

| 'Jan kept nagging about his boss during the entire meeting.' | |||||

Table 28 provides a list of temporal circumpositions classified according to their second part. A comparison of this table with Table 19 reveals that the number of temporal circumpositions is much smaller than the number of spatial ones.

| 2nd part | circumposition | example | translation |

| aan | tegen ... aan | ?tegen de avond aan | towards the evening |

| af | van ... af | van dat moment af | since that moment |

| door | tussen ... door | tussen de lessen door | in between the lessons |

| heen | door ... heen | door de jaren heen | throughout the years |

| in | tussen ... in | tussen kerst en Nieuwjaar in | between Christmas and New Year |

| toe | naar ... toe | naar kerstmis toe | towards Christmas |

| tot ... (aan) toe | tot de ochtend (aan) toe | until the morning |

As in the case of the temporal postpositions the complement of these temporal circumpositions is, broadly speaking, restricted to noun phrases denoting conventional time units. The only exception seems to be tussen ... door/in. In (377) we give an example for each case.

| a. | Tegen | de avond | (?aan) | kom | ik | naar huis. | |

| towards | the evening | aan | come | I | to home | ||

| 'Towards evening I will come home.' | |||||||

| b. | Van | dat moment | *(af ) | wilde | hij | schilder | worden. | |

| from | that moment | af | wanted | he | painter | become | ||

| 'From that moment he wanted to be a painter.' | ||||||||

| c. | Jan rookt | tussen | de lessen | (door). | |

| Jan smokes | between | the lessons | door | ||

| 'Jan smokes in between the classes.' | |||||

| d. | Door | de jaren | (heen) | is het dorp | steeds | groter | geworden. | |

| through | the years | heen | is the village | continuously | bigger | become | ||

| 'Throughout the years the village has kept on growing.' | ||||||||

| e. | Tussen | die twee lessen | ?(in) | werd | Jan gearresteerd. | |

| between | those two lessons | IN | was | Jan arrested | ||

| 'Jan was arrested between those two lessons.' | ||||||

| f. | Het | loopt | al | naar | de dageraad | *(toe). | |

| it | walks | already | towards | the dawn | toe | ||

| 'It is near dawn.' | |||||||

The examples in (377) show that the second part of the circumposition can be omitted in many cases without any noticeable effect on the meaning of the examples. This is probably because we are not really dealing with circumpositions but with prepositional phrases emphasized by a particle; cf. 32.3.1.4, sub II, where we suggested the same thing for apparent circumpositional phrases with a locational interpretation.

Example (378) shows that the circumposition van ... af in (377b) alternates with the complex preposition vanaf, again without any clear effect on the meaning.

| Vanaf dat moment | wilde | hij | schilder | worden. | ||

| from that moment | wanted | he | painter | become | ||

| 'From that moment on he wanted to become a painter.' | ||||||

Example (379) is also noteworthy because the complement seems to involve a noun (kindchild) or adjective (jongyoung) suffixed with -s; these circumpositional phrases are idiomatic in nature, and also occur with an additional aan: van kinds/jongs af (aan).

| Van | kinds/jongs | *(af) | wilde | hij | schilder | worden. | ||

| from | childhood | af | wanted | he | painter | become | ||

| 'Ever since he was a child, he wanted to become a painter.' | ||||||||

Finally, note that example (380) probably does not contain a circumpositional phrase tot (aan) ... toe; we seem to be dealing with the preposition totuntil followed by an adpositional complement. This is at least suggested by the fact that the latter can be replaced by the pro-form danthen; cf. Section 33.2.1.

| a. | Het feest | duurt | tot | (aan) | de ochtend | toe. | |

| the party | lasts | until | aan | the morning | toe | ||

| 'The party will last until the morning.' | |||||||

| b. | Het feest | duurt | tot | dan. | |

| the party | lasts | until | then |