- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Section 1.5.1 discussed the binary tense theory proposed in Te Winkel (1866) and Verkuyl (2008), according to which the three binary distinctions in (376) are used in mental representations of tense. Languages may differ in the grammatical means used to express the oppositions in (376): this may be done in the verbal system by inflection and/or auxiliaries, but it may also involve the use of adverbial phrases, aspectual markers, pragmatic information, etc. Verkuyl claimed that Dutch expresses all the oppositions in (376) in the verbal system: [+past] is expressed by inflection, [+posterior] by the verb zullenwill, and [+perfect] by the auxiliaries hebbento have and zijnto be.

| a. | [±past]: present versus past |

| b. | [±posterior]: future versus non-future |

| c. | [±perfect]: imperfect versus perfect |

Section 1.5.2 has argued at length that the claim that zullen is a future auxiliary is incorrect: it is an epistemic modal, and it is only because of pragmatic considerations that examples with zullen are sometimes interpreted with a future time reference; cf. also Broekhuis & Verkuyl (2014). If this is true, then the Dutch verbal system only expresses the binary features [±past] and [±perfect]; it does not make an eightfold, but only a fourfold tense distinction based on inflection and auxiliaries. This means that the traditional view on the Dutch verbal tense system in Table 9 from Section 1.5.1, sub I, must be replaced by the one in Table 11; the verb zullen is no longer seen as a marker of a separate set of future tenses. Of course, this does not mean that the future tense is not relevant for Dutch, but only that posteriority must be expressed by other means (e.g. the use of time adverbials such as morgentomorrow).

| present | past | |

| imperfect | simple present (o.t.t.) Ik wandel/Ik zal wandelen. I walk/I will walk | simple past (o.v.t.) Ik wandelde/Ik zou wandelen. I walked/I would walk |

| perfect | present perfect (v.t.t.) Ik heb gewandeld/ Ik zal hebben gewandeld. I have walked/I will have walked | past perfect (v.v.t.) Ik had gewandeld/ Ik zou hebben gewandeld. I had walked/I would have walked |

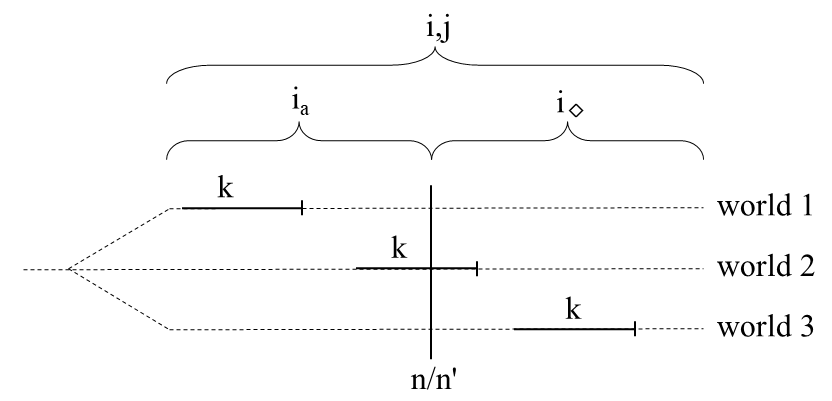

This revised view on the Dutch verbal tense system implies that utterances in the simple present/past can normally refer to any event time interval in the present/past-tense interval i; eventuality k can precede, overlap or follow n/n', as shown in Figure 24. Recall that the number of possible worlds is in principle infinite and that we simply select a number of them that suit our purpose.

The representation of the perfect tenses is virtually identical to that in Figure 24, the only difference being that the eventualities are construed as completed autonomous units within the present/past-tense interval. As before, we indicate this in Figure 25 by a vertical line at the end of the event time interval k.

In the figures above we have assumed that the default value of the present j of eventuality k (i.e. the time interval within which the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb must take place) is equal to that of the complete present/past-tense interval i. The following sections will show that contextual information (linguistic and non-linguistic) can override this default interpretation and lead to more restricted interpretations.

Before proceeding with a discussion of the Dutch verbal tense system, we would like to note that although Verkuyl (2008) was probably wrong in assuming that the binary tense theory is perfectly reflected in this system, it seems that Dutch is very suitable for studying the interaction of tense, modality and pragmatic information, because it can be characterized as a strongly “tense-oriented” language. First, Dutch does not normally mark mood on the verb (the exception being imperative marking), so it differs from German in that it does not have a productive subjunctive marking on the verb; cf. Section 1.4.3. Second, Dutch does not normally mark syntactic aspect on the verb, so it differs from English in that progressive aspect can be expressed by using the simple present/past. Third, Dutch does not require epistemic modality to be marked, so it differs from English in that the expression of non-actualized (“future”) events need not be marked by the modal will; Dutch zullen is optional in such cases. Finally, it may be useful to mention that adverbial phrases such as gisterenyesterday that refer to temporal intervals preceding speech time can be used in Dutch present-perfect constructions, i.e. Dutch does not have the property found in English that such adverbials can only be used in past-tense constructions: cf. Broekhuis (2021) and Verkuyl (2022: §3.3.3) for two possible accounts of this contrast from a binary tense perspective. All in all, this means that Dutch allows us to directly investigate the interaction of past tense, epistemic modality, and pragmatics in the derivation of special meaning effects, without the intervention of any of the more idiosyncratic properties concerning mood/modality, aspect and adverbial modification of the type mentioned above.