- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Verbs: Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I: Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 1.0. Introduction

- 1.1. Main types of verb-frame alternation

- 1.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 1.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 1.4. Some apparent cases of verb-frame alternation

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa: Selected clauses/verb phrases (introduction)

- 4.0. Introduction

- 4.1. Semantic types of finite argument clauses

- 4.2. Finite and infinitival argument clauses

- 4.3. Control properties of verbs selecting an infinitival clause

- 4.4. Three main types of infinitival argument clauses

- 4.5. Non-main verbs

- 4.6. The distinction between main and non-main verbs

- 4.7. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb: Argument and complementive clauses

- 5.0. Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 5.4. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc: Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId: Verb clustering

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I: General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II: Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- 11.0. Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1 and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 11.4. Bibliographical notes

- 12 Word order in the clause IV: Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 14 Characterization and classification

- 15 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 15.0. Introduction

- 15.1. General observations

- 15.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 15.3. Clausal complements

- 15.4. Bibliographical notes

- 16 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 16.2. Premodification

- 16.3. Postmodification

- 16.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 16.3.2. Relative clauses

- 16.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 16.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 16.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 16.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 17.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 17.3. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Articles

- 18.2. Pronouns

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Numerals and quantifiers

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Numerals

- 19.2. Quantifiers

- 19.2.1. Introduction

- 19.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 19.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 19.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 19.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 19.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 19.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 19.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 19.5. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Predeterminers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 20.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 20.3. A note on focus particles

- 20.4. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 22 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 23 Characteristics and classification

- 24 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 25 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 26 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 27 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 28 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 29 The partitive genitive construction

- 30 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 31 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- 32.0. Introduction

- 32.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 32.2. A syntactic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 32.4. Borderline cases

- 32.5. Bibliographical notes

- 33 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 34 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 35 Syntactic uses of adpositional phrases

- 36 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 32 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Syntax

-

- General

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

Like interrogative pronouns, quantificational personal pronouns can be divided into [+human] and [-human] forms. The [+human] forms are the existential pronoun iemandsomeone and the universal pronoun iedereen and, in writing, (een)ieder and elkeen, both of which belong to the formal register and are somewhat archaic. Their [-human] counterparts are ietssomething, or its more colloquial alternate wat, and allesall. The [+human] and [-human] existential pronouns both have negative counterparts, which are niemandnobody and niets or its colloquial alternant niksnothing, respectively.

| [+human] | [-human] | ||

| existential | positive | iemand ‘someone’ | iets/wat ‘something’ |

| negative | niemand ‘nobody’ | niets/niks ‘something’ | |

| universal | iedereen ‘everybody’ | alles ‘everything’ | |

The following subsections discuss some properties of the pronouns in Table 9. Before doing so, we want to note that in traditional grammars forms like sommige(n)some, vele(n)many and alle(n)all are also categorized as personal pronouns. However, since these forms can be seen as nominalizations of the corresponding quantificational modifiers, they will be discussed in Section 19.2.

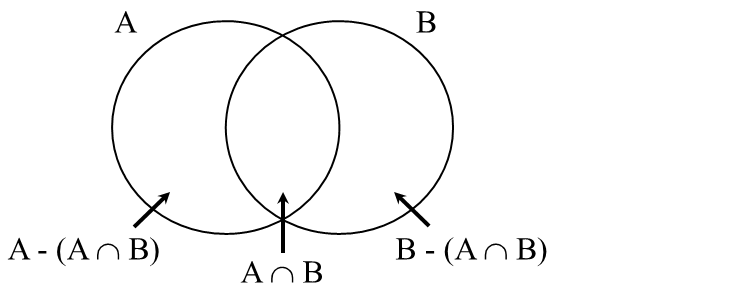

The simplest way to explain the core meaning of quantificational personal pronouns is to use Figure 1 from Section 14.1.2, sub IIA, repeated below, to represent the subject-predicate relation in a clause. In this figure, A represents the denotation set of the lexical part (i.e. the NP-part) of the subject and B the set of entities denoted by the verb phrase. The intersection A ∩ B denotes the set of entities for which the proposition expressed by the clause is claimed to be true. For instance, in an example such as De jongen wandelt op straat, it is claimed that set A, which has cardinality 1, is properly contained in set B, which consists of the people walking in the street. In other words, it is expressed that A - (A ∩ B) is empty.

In the following discussion we will not be interested in the fact that the [+human] and [-human] pronouns are associated with two mutually exclusive denotation sets: for the former, set A is a set of individuals, while for the latter, set A is a set of non-human entities. We will rather focus on the implication of the pronouns for the intersection A ∩ B and the remainder of set A, i.e. A - (A ∩ B).

The existential pronouns iemand and iets behave similarly to indefinite noun phrases in that they indicate that A ∩ B is not empty, and do not imply anything about the set A - (A ∩ B), which may or may not be empty.

| a. | Er | loopt | iemand | op straat. | |

| there | walks | someone | in the.street | ||

| 'There is someone walking in the street.' | |||||

| a'. | iemand: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 |

| b. | Er | zit | iets | in die doos. | |

| there | sits | something | in that box | ||

| 'There is something in that box.' | |||||

| b'. | iets: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 |

Note that unlike what we did with singular indefinite noun phrases (see example (8) in Section 18.1.1.1), here we follow the philosophical tradition of assuming that the existential pronouns express that the cardinality of the intersection A ∩ B is ≥ 1. The reason for this is that they can be used in yes/no-questions without implying that there is at most one person/entity that satisfies the description given by the verb phrase. This will be clear from the fact that the question-answer pairs in (398) form a perfectly coherent piece of interaction.

| a. | Komt | er | vanavond | iemand? | Ja, | Jan en Peter | met hun partner. | |

| comes | there | tonight | someone | yes | Jan and Peter | with their partner | ||

| 'Is there anyone coming tonight? Yes, Jan and Peter with their partners.' | ||||||||

| b. | Zit | er | nog | iets | in die doos? | Ja, | een paar boeken. | |

| sits | there | still | something | in that box | yes | a couple of books | ||

| 'Is there still something in that box? Yes, a couple of books.' | ||||||||

While the semantic contribution of existential pronouns is similar to that of indefinite noun phrases, universal pronouns are instead similar to definite noun phrases: they express that in the domain of discourse (domain D) all entities that satisfy the description of the pronoun (human/non-human) are included in the intersection A ∩ B, i.e. that the remainder of the set is empty: |A - (A ∩ B)| = 0.

| a. | Iedereen | loopt | op straat. | |

| everyone | walks | in the.street |

| a'. | iedereen: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| = 0 |

| b. | Alles | zit | in de doos. | |

| everything | is | in the box |

| b'. | alles: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| = 0 |

Now that we have seen that the existential and the universal personal pronouns resemble noun phrases containing, respectively, an indefinite and a definite article, it is not surprising that the negative existential personal pronouns resemble noun phrases containing the negative article/quantifier geenno: they express that the intersection (A ∩ B) is empty.

| a. | Er | loopt | niemand | op straat. | |

| there | walks | no.one | in the.street | ||

| 'There is no one walking in the street.' | |||||

| a'. | niemand: |A ∩ B| = 0 |

| b. | Er | zit | niets | in die doos. | |

| there | sits | nothing | in that box | ||

| 'There is nothing in that box.' | |||||

| b'. | niets: |A ∩ B| = 0 |

The examples in (401) and (402) show that all quantificational personal pronouns are formally third-person singular and masculine (or neuter): this is clear from the form of the finite verb and from the fact that the third-person possessive pronoun zijnhis can take the quantificational pronoun as its antecedent. Note, however, that the use of feminine pronouns is encouraged for politically correct writing/speech.

| a. | Er | heeft/*hebben | iemandi | zijni auto | verkeerd | geparkeerd. | |

| there | has/have | someone | his car | wrongly | parked |

| b. | Er | heeft/*hebben | niemandi | zijni auto | verkeerd | geparkeerd. | |

| there | has/have | no.one | his car | wrongly | parked |

| c. | Iedereeni | heeft/*hebben | zijni auto | verkeerd | geparkeerd. | |

| everyone | has/have | his car | wrongly | parked |

| a. | Er | ligt/*liggen | ietsi | uit | zijni doos. | |

| there | lies/lie | something | out.of | his box | ||

| 'There is something out of its box.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | ligt/*liggen | nietsi | uit | zijni doos. | |

| there | lies/lie | nothing | out.of | his box | ||

| 'There is nothing out of its box.' | ||||||

| c. | Allesi | ligt/*liggen | in zijni doos. | |

| everything | lies/lie | in his box | ||

| 'Everything is in its box.' | ||||

The fact that the existentially quantified subject pronouns in (401a) and (402a) co-occur with the expletive erthere shows that they can be weak noun phrases. However, the examples in (403) show that these quantificational personal pronouns can also be strong, i.e. they can also occur in the regular subject position.

| a. | Er | heeft | iemand | gebeld. | |||||

| there | has | someone | called | ||||||

| 'Someone has called.' | |||||||||

| b. | Er | is | iets | gevallen. | |||||

| there | is | something | fallen | ||||||

| 'Something has fallen.' | |||||||||

| a'. | ? | Iemand heeft gebeld. |

| b'. | ?? | Iets is gevallen. |

The primed examples, however, are marked in the sense that they require a special intonation pattern: they are only natural when the existential pronoun is assigned accent. The pronouns in the primed examples then receive a specific indefinite reading, which can be paraphrased een zeker persoon/dinga certain person/thing. The pronouns in the primeless examples, on the other hand, can be interpreted non-specifically, which is clear from the fact that they can be paraphrased by een of ander persoon/dingsome person/thing. The examples in (404) show that the more colloquial existential pronoun wat differs from iets in that it can only occur with the expletive, which shows that wat can only be interpreted non-specifically.

| a. | Er | is | wat | gevallen. | |

| there | is | something | fallen | ||

| 'Something has fallen.' | |||||

| b. | * | Wat is gevallen. |

The fact that the existential pronouns in (403a&b) can be interpreted non-specifically does not mean that they must be interpreted that way. In fact, there is reason to think that they can have both a non-specific and a specific reading. The two readings can be made prominent by adding a quantified adverbial phrase such as verschillende kerenseveral times to the sentence. When the existential pronoun follows the adverbial phrase, as in (405), it can only be interpreted non-specifically, which is clear from the fact that it can then range over a non-singleton set of entities, i.e. that several persons have called or several things have fallen. This interpretation is usually expressed by saying that the existential pronoun is in the scope of the quantified adverbial phrase verschillende keren.

| a. | Er | heeft | verschillende keren | iemand | gebeld. | |

| there | has | several times | someone | called |

| b. | Er | is | verschillende keren | iets/wat | gevallen. | |

| there | has | several times | something | fallen |

When the existential pronoun precedes the adverbial phrase, however, it must receive a specific interpretation; in (406a) the phone calls were all made by the same person, whose identity is concealed by the speaker; in (406b) it is a certain thing, not further specified, that has fallen several times. Note that iets in (406b) cannot be replaced by wat, which supports the claim made on the basis of (404) that wat is inherently non-specific.

| a. | Er | heeft | iemand | verschillende keren | gebeld. | |

| there | has | someone | several times | called |

| b. | Er | is | iets/*wat | verschillende keren | gevallen. | |

| there | has | something | several times | fallen |

Although the specific interpretation can in principle be expressed by saying that the existential pronoun has the quantified phrase in its scope, this may be beside the point, since a similar difference in meaning can be found in (407), where the adverbial phrase is not quantificational in nature. It seems easier, therefore, to simply assign to iemand/iets the reading “a certain person/thing” when it precedes a clause adverbial; cf. Hornstein (1984) for a similar claim concerning English existentially quantified noun phrases.

| a. | Er | heeft | gisteren | iemand | gebeld. | |

| there | has | yesterday | someone | called |

| b. | Er | heeft | iemand | gisteren | gebeld. | |

| there | has | someone | yesterday | called |

Note that although we can paraphrase the specific and non-specific readings of iemand and iets by means of indefinite noun phrases preceded by the indefinite article een, the former differs from the latter in that it does not allow a generic interpretation: while the generic sentence in (408b) is perfectly acceptable, example (408a) certainly cannot be interpreted generically.

| a. | *? | Iemand | is sterfelijk. |

| someone | is mortal |

| b. | Een mens | is sterfelijk. | |

| a human being | is mortal | ||

| 'Man is mortal.' | |||

Possible exceptions to the general rule that iemand and iets cannot be used generically are given in (409), taken from Haeseryn et al. (1997), which are special in that they contain two conjoined predicates that are mutually exclusive.

| a. | Iemand | is getrouwd of ongetrouwd. | |

| someone | is married or not.married |

| b. | Iets | is waar of niet waar. | |

| something | is true or not true |

Of course, generic meanings can be and are in fact typically expressed by universal pronouns; cf. Iedereen is sterfelijkEveryone is mortal and Alles is vergankelijkEverything is transient.

The negative existential personal pronouns niemandnobody and niets/niksnothing are normally used as weak quantifiers, which is clear from the fact that as subjects they are preferably used in an expletive construction. Examples like (410a'&b') are acceptable, but generally require emphatic accent: the pronoun then receives an emphatic reading comparable to the “not a single N” reading of noun phrases with geen; cf. Section 18.1.5.1, sub III.

| a. | Er | heeft | niemand | gebeld. | |||||

| there | has | nobody | called | ||||||

| 'Nobody has called.' | |||||||||

| b. | Er | is | niets | gevallen. | |||||

| there | is | nothing | fallen | ||||||

| 'Nothing has fallen.' | |||||||||

| a'. | Niemand | heeft | gebeld. | |||

| nobody | has | called | ||||

| 'Not a single person called.' | ||||||

| b'. | Niets | is gevallen. | ||||

| nothing | is fallen | |||||

| 'Not a single thing fell.' | ||||||

The negative pronouns niemand and niets are probably best thought of as the negative counterparts of the non-specific pronouns iemand and iets: if we want to negate a sentence containing the specific forms of these pronouns, the negation is expressed not by the pronoun, but by the negative adverb niet. Example (411) shows that the specific quantificational pronoun must precede this adverb. For completeness, note that in accordance with the earlier suggestion that it is inherently non-specific, wat cannot substitute for iets in (411b).

| a. | Er | heeft | iemand | niet | gebeld. | |

| there | has | someone | not | called | ||

| 'A certain person didnʼt call.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | is iets/*wat | niet | gevallen. | |

| there | is something | not | fallen | ||

| 'A certain thing didnʼt fall.' | |||||

Unlike the existential pronouns (cf. (408a)), the negative existential pronouns in (412) can easily be used in generic statements. In such examples the negative pronouns behave like strong quantifiers, i.e. they cannot be used in an expletive construction.

| a. | Niemand | is | onsterfelijk. | |||

| nobody | is | immortal | ||||

| 'Nobody is immortal.' | ||||||

| b'. | Niets | is tevergeefs. | ||||

| nothing | is in.vain | |||||

| 'Nothing is in vain.' | ||||||

| a'. | ?? | Er is niemand onsterfelijk. |

| b'. | ?? | Er is niets tevergeefs. |

Quantificational pronouns can be used in all regular argument positions. In (413) and (414) this is illustrated for the subject and object position, respectively.

| a. | Er | ligt | iemand/iets | op mijn bed. | |

| there | lies | someone/something | on my bed | ||

| 'There is someone/something lying on my bed.' | |||||

| b. | Er | ligt | niemand/niets | op mijn bed. | |

| there | lies | no.one/nothing | on my bed | ||

| 'There is no one/nothing lying on my bed.' | |||||

| c. | Iedereen/Alles | ligt | op mijn bed. | |

| everybody/everything | lies | on my bed |

| a. | Jan heeft | iemand/iets | weggebracht. | |

| Jan has | someone/something | away-brought | ||

| 'Jan has seen of someone/something.' | ||||

| b. | Jan heeft | niemand/niets | weggebracht. | |

| Jan has | no.one/nothing | away-brought | ||

| 'Jan has seen off no one/nothing.' | ||||

| c. | Jan heeft | iedereen/alles | weggebracht. | |

| Jan has | everyone/everything | away-brought | ||

| 'Jan has seen everyone/everything off.' | ||||

The examples in (415) show that [+human] quantificational personal pronouns can also be used as the complement of a preposition. The existential pronoun in (415a) can be either specific or non-specific, and its negative counterpart in (415b) is interpreted with its normal, non-emphatic reading.

| a. | Jan wil | op iemand | wachten. | |

| Jan wants | for someone | wait | ||

| 'Jan wants to wait for someone.' | ||||

| b. | Jan wil | op niemand | wachten. | |

| Jan wants | for no.one | wait | ||

| 'Jan does not want to wait for anyone.' | ||||

| c. | Jan wil | op iedereen | wachten. | |

| Jan wants | for everyone | wait | ||

| 'Jan wants to wait for everyone.' | ||||

The situation is somewhat more complex with the [-human] pronouns, due to the fact that they can undergo R-pronominalization, i.e. the primeless examples in (416) alternate with the primed examples.

| a. | P iets |

| a'. | ergens ... P | existential |

| b. | P niets |

| b'. | nergens ... P | negative existential |

| c. | P alles |

| c'. | overal ... P | universal |

The examples in (417) show that the existential pronoun iets alternates with the R-word. The judgments are somewhat subtle, but it seems that (417a) is preferably interpreted as specific, while (417b) instead receives a non-specific interpretation.

| a. | Jan wil | op iets | wachten. | existential | |

| Jan wants | for something | wait | |||

| 'Jan wants to wait for something.' | |||||

| b. | Jan wil | ergens | op wachten. | |

| Jan wants | somewhere | for wait | ||

| 'Jan wants to wait for something.' | ||||

With the negative existential pronouns, R-pronominalization seems to be the unmarked option. Realizing the pronoun as the complement of the preposition seems to yield a “not a single thing” reading.

| a. | Jan wil | op niets | wachten. | negative existential | |

| Jan has | for nothing | wait | |||

| 'Jan does not want to wait for anything.' | |||||

| b. | Jan wil | nergens | op wachten. | |

| Jan wants | nowhere | for wait | ||

| 'Jan does not want to wait for anything.' | ||||

With the universal pronoun, R-pronominalization may also be the unmarked option. Realizing the pronoun as the complement of the preposition seems to yield an emphatic “each and everything” reading.

| a. | Jan wil | op alles | wachten. | universal | |

| Jan wants | for everything | waited | |||

| 'Jan wants to wait for everything.' | |||||

| b. | Jan wil | overal | op | wachten. | |

| Jan wants | everywhere | for | wait | ||

| 'Jan wants to wait for everything.' | |||||

The above observations are admittedly rather impressionistic, so more research is needed to determine whether the R-forms are indeed unmarked, and whether the two forms do indeed exhibit systematic meaning differences of the kind suggested here.

Finally, we note that the existential pronouns can also be used as the predicate in a copular construction, although they usually require some form of modification. This is illustrated in (420) for the non-specific use of the pronouns.

| a. | Jan is iemand van mijn school. | |

| Jan is someone from my school |

| b. | Die gewoonte | is | nog | iets | uit mijn schooltijd. | |

| that habit | is | still | something | from my school.days |

The negative existential pronouns in (421) can also be used as complementives, although this results in a more or less idiomatic interpretation.

| a. | Jan is niemand. | |

| Jan is no.one | ||

| 'Jan is a nobody.' |

| b. | Dat probleem | is niets. | |

| that problem | is nothing | ||

| 'That problem is of no importance.' | |||

The universal pronouns in (422) also have a severely limited distribution with a more or less idiomatic interpretation.

| a. | Dat | is alles. | |

| that | is all | ||

| 'That is all (I have to say).' | |||

| a'. | Dat is nog | niet | alles. | |

| that is yet | not | all | ||

| 'And there is more (to say/on offer/...).' | ||||

| a''. | Dat | is | ook | niet | alles. | |

| that | is | also | not | all | ||

| 'That has its problems too.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | ben | (dan | ook) | niet iedereen. | |

| I | am | prt | prt | not everyone | ||

| 'I am rather special (after all).' | ||||||

The predicatively used existential pronouns in the primeless examples of (423) are followed by a relative clause and receive a specific interpretation, which is clear from the fact that their negative counterparts in the (b)-examples do not involve the negative existential pronouns, which are preferably construed as non-specific, but the negative adverb niet.

| a. | Hij | is | iemand | [met wie | je | gemakkelijk | kan praten]]. | |

| he | is | someone | with whom | you | easily | talk can | ||

| 'He is someone with whom one can talk easily.' | ||||||||

| a'. | Hij | is | niet | [iemand | [met wie | je | gemakkelijk | kan praten]]. | |

| he | is | not | someone | with whom | you | easily | talk can |

| b. | Dat is iets | [om | rekening | mee | te houden]. | |

| that is something | comp | account | with | to keep | ||

| 'This is something to take into account.' | ||||||

| b'. | Dat | is niet | iets | [om | rekening | mee | te houden]. | |

| that | is not | something | comp | account | with | to keep |

Examples (420) and (423) have already shown that predicatively used existential pronouns can be modified. Quantificational personal pronouns in argument position often occur with postmodifiers, which then function to restrict the sets denoted by the pronouns. This is illustrated in (424) by the [+human] quantificational pronouns. In all these examples the (contextually determined) set of persons is restricted to a subset of it.

| a. | Iemand uit de keuken/daar | heeft | een mes | in zijn hand | gestoken. | |

| someone from the kitchen/there | has | a knife | into his hand | stuck | ||

| 'Someone from the kitchen/over there has stuck a knife into his hand.' | ||||||

| a'. | Iemand | die | niet goed | oplette, | heeft | een mes | in zijn hand | gestoken. | |

| someone | who | not well | prt.-attended | has | a knife | into his hand | stuck | ||

| 'Someone who didnʼt pay attention has stuck a knife into his hand.' | |||||||||

| b. | Iedereen op mijn werk/hier | is ziek. | |

| everyone at my work/here | is ill |

| b'. | Iedereen | die | goed | oplet, | zal | het examen | zeker | halen. | |

| everyone | who | well | prt.-attends | will | the exam | certainly | pass | ||

| 'Everyone who pays attention in class will certainly pass the exam.' | |||||||||

Premodification by an attributive adjective, on the other hand, seems to be ruled out. Note that an example such as (425a) is only an apparent counterexample to this claim: the fact that the form iemand is preceded by an indefinite article indicates that the pronoun is simply being used as a noun, comparable in meaning to a noun like persoonperson. Example (425b) shows that iets can be used in a similar way with the meaning “thing”; however, wat is completely unacceptable in such constructions. Note that the constructions in (425) actually require the presence of an attributive modifier; cf. *een iemand and *een iets.

| a. | een | keurig/aardig | iemand | |

| a | neat/nice | someone | ||

| 'a neat/nice person' | ||||

| b. | een | leuk | ?iets/*wat | |

| a | nice | something | ||

| 'a nice thing' | ||||

Existential pronouns can be modified in two other ways. First, these pronouns can be followed by the element anderselse. These constructions are discussed in more detail in Section A29.4.

| a. | iemand | anders | |

| someone | else |

| b. | iets/wat | anders | |

| something | else |

Second, the existential pronouns iemand and iets can be premodified by zosuch, which results in a “type” reading of the quantifier. The pronoun wat lacks this option, which is clear from the fact that a Google search (December 1, 2015) for the string [ook zo iets gelezen] yielded 31 hits, while no relevant results were obtained for the string [ook zo wat gelezen].

| a. | Ik | ken | ook | zo iemand. | |

| I | know | also | such someone | ||

| 'I also know a person like that.' | |||||

| b. | Ik | heb | onlangs | ook | zo iets/*?wat | gelezen. | |

| I | have | recently | also | such something | read | ||

| 'I have also read a thing like that recently.' | |||||||