- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

Classical binding theory is primarily concerned with accounting for the fact that referential personal pronouns and anaphors (i.e. reflexive and reciprocal personal pronouns) are in complementary distribution. We noted in Section 23.2 that the literature on binding has focused mainly on nominal and prepositional arguments of verbs: referential pronouns and anaphors embedded in complementives and adjuncts have received far less attention. The reason for this may be that the patterns established for arguments of verbs are relatively clear compared to the patterns that emerge for other clausal constituents. Subsection I discusses a number of cases for which it has been argued that the mutual exclusion of referential pronouns and anaphors does not hold. It is also shown that, despite these (partly true and partly apparent) counterexamples, the original generalization still stands firm. However, we will find that our tentative definition of the local binding domain as the minimal clause of the referential pronoun/anaphor is in need of revision. Subsection II revisits this notion in more detail and provides a new definition that expands the empirical scope of binding theory by considering the binding behavior of referential pronouns and anaphors embedded in complementives.

The literature on binding theory has mainly focused on the binding relation between (nominal and prepositional) arguments of verbs: referentially dependent elements embedded in complementives and adjuncts have received much less attention. This subsection will examine the claim that the mutual exclusion of complex anaphors and referential personal pronouns holds only for arguments, and we will argue that it is not evident that such claims indeed hold true.

Reinhart & Reuland (1993) explicitly claim that binding conditions A and B are restricted to co-arguments, i.e. the subject and the nominal and prepositional complements of a verb or some other argument-taking lexical head. Their version of binding theory, often referred to as the reflexivity framework, is based on the assumption that the self-morpheme of morphologically complex reflexives such as zichzelf marks the reflexivity of the predicate (reciprocals such as each other are assumed to have a similar effect). This is expressed by reformulating the binding conditions A and B, as in (133).

| a. | Condition A: a reflexive-marked predicate is reflexive. |

| b. | Condition B: a reflexive predicate is reflexive-marked. |

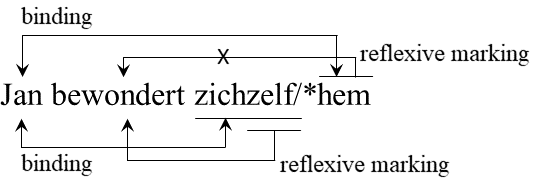

The intended interpretation of the conditions is as follows. First, a complex anaphor such as zichzelf marks its predicate as reflexive, and condition A can therefore only be satisfied if the complex anaphor is bound by a co-argument; this condition is satisfied in Jan bewondert zichzelf Jan admires himself in (134), since the morpheme –zelf of the complex reflexive marks the verb as reflexive, and the complex reflexive is bound by its co-argument Jan. Condition B states that binding by a co-argument is allowed only if the predicate is reflexive marked by one of its arguments (unless it is inherently reflexive, as in zich vergissento be mistaken, an option ignored here for the sake of simplicity); this rules out binding of the referential pronoun in Jan bewondert hemJan admires him in (134) by its co-argument Jan, since it lacks a morpheme that marks the predicate as reflexive.

|

The revised version of the theory in (133) can only be applied to arguments, so it implies that complex self-forms enter into two different kinds of relation with an antecedent, which Reinhart & Reuland refer to as anaphoric and logophoric (the latter term being used in a broader sense than usual): complex anaphors are arguments that must be bound by a co-argument; logophors are non-arguments that can enter into a wider range of referential dependencies and are therefore expected to occur in similar configurations as referential pronouns, at least in some cases. The claim is based on English examples like those in (135), where the self-forms occur without an antecedent in the sentence, in violation of the classical formulation of binding condition A: the self-forms are logophors referring to some discourse participant (here: the speaker or the addressee).

| a. | There were five people in the room apart from myself. | part of adjunct |

| b. | Physicists like yourself are a godsend. | embedded in an argument |

| c. | She gave both Brenda and myself a book. | part of a coordinate structure |

Reinhart & Reuland claim that similar examples can also be found in Dutch, and translate the English example (135a) as (136a). However, (136a) with the self-form mezelf is problematic for several reasons. For instance, mezelf alternates with the nominative form ikzelf in (136b), which is even given as the preferred option by language advice services; cf. taaladvies.net/taal/advies/vraag/1329 and the references cited there.

| a. | Er | waren vijf mensen | in de kamer | behalve mezelf. | |

| there | were five people | in the room | apart.from me-self |

| b. | Er | waren | vijf mensen | in de kamer | behalve ikzelf. | |

| there | were | five people | in the room | apart.from I-self |

The relevant point here is not whether (136a) is part of the standard language or not, but that (136b) is undoubtedly well-formed. Since there are no nominative reflexive pronouns in Dutch, the morpheme zelf in this example is not part of a complex self-form, but an instantiation of the emphatic modifier zelf associated with the referential personal subject pronoun ikI; cf. Section 19.2.3.2, sub V. This strongly suggests that example (136a) is not a complex self-form either, but should also be analyzed as a case with the referential personal object pronoun me modified by the emphatic modifier zelf. A similar argument can be used to argue that jijzelf in the rendering of example (135b) in (137a) is not a self-anaphor: strong jij is a subject form, and the weak subject/object form je, which is normally used as the first morpheme of the self-anaphor (cf. Table 11 in Section 19.2.1.5), leads to a degraded result. The fact that the rendering of (135c) in (137b) is also degraded with a weak object form again suggests that we are not dealing with self-forms but with regular referential pronouns. For comparison, we have added the forms without the emphatic modifier zelf in the primed examples; note that the unacceptability of the weak forms is not syntactic in nature, but due to the fact that the position in which they occur cannot be filled by a phonetically light constituent.

| a. | Natuurkundigen | zoals jijzelf/*jezelf | zijn | een zegen. | |

| physicists | like you-self | are | a blessing |

| a'. | Natuurkundigen | zoals jij/*je | zijn | een zegen. | |

| physicists | like you | are | a blessing |

| b. | Ze | gaf | zowel | Brenda | als mijzelf/*mezelf | een boek. | |

| she | gave | both | Brenda | and me-self | a book |

| b'. | Ze | gaf | zowel | Brenda | als mij/*me | een boek. | |

| she | gave | both | Brenda | and me | a book |

The examples in (135)-(137) all involve first-person and second-person pronouns without an antecedent. The attested example (138a), again taken from Reinhart & Reuland (1993), involves a third-person pronoun with an antecedent external to its minimal clause. The attested standard Dutch example in (138b) again provides an argument against analyzing examples of this kind as logophoric: zelf modifies the subject pronoun zijshe and thus does not involve a morphologically complex self-form of the kind intended by Reinhart & Reuland; moreover, substituting zichzelf for zijzelf would make the example unacceptable.

| a. | Clara found time to check that apart from herself there was a man from the BBC. |

| b. | De heldin [...] is zo antipathiek dat de schrijfster er zelf van uitging dat behalve zijzelf niemand haar aardig zou vinden. [Blurb of the Dutch translation of Jane Austin’s Emma’ published by Athenaeum in 2012] | |

| 'The heroine [...] is so antipathetic that the author herself assumed that no one but herself would like her.' |

The attested examples in (139) are similar to the two remaining examples in Reinhart & Reuland and show again that we are probably dealing with emphatic zelf: it follows the pronominal subject form hijhe, and replacing hijzelf with zichzelf would make the examples unacceptable.

| a. | Hij vroeg zich af hoe het kwam dat een man als hijzelf [...] op dergelijke manier vernederd kon worden. [https://lib.ugent.be/fulltxt/RUG01/001/391/ 490/RUG01-001391490_2010_0001_AC.pdf] | |

| 'He wondered how it was possible that a man like himself [...] could be humiliated in such a way.' |

| b. | De minister-president zegt dat minister Asscher en hijzelf de volle regie hebben. | |

| [https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/h-tk-20122013-66-2.html] | ||

| 'The Prime Minister says that Minister Asscher and himself are in full control.' |

The Dutch counterparts of the English examples provided by Reinhart and Reuland (or by Reuland 2011) do not support the claim that complex self-forms such as zichzelf can be used both as anaphors and as logophors; indeed, we are not aware of any cases that would support such a view. Reformulations of the binding theory such that binding conditions A and B apply only to arguments cannot therefore account for the distribution of complex reflexive and referential personal pronouns in the other cases discussed in Section 23.2, sub I/II, without additional stipulations. Consider, for example, (140a) with a reflexive/referential pronoun embedded in an adverbial PP. Reuland (2011:359, n.30) accounts for the complementary distribution of zichzelf and hem by claiming (without any independent semantic or syntactic justification) that the adverbial PP is a reflexive two-place predicate with a phonetically empty nominal argument x, i.e. [PP xi namens zichzelfi/*hemi]. That this analysis is highly problematic can be seen from the fact that it incorrectly predicts the impersonal passive counterpart of (140a) in (140b) to be possible with zichzelf, since it would still be bound by the supposedly empty argument x within PP.

| a. | Jan sprak [PP | namens zichzelf/*hem]. | active | |

| Jan spoke | on.behalf.of himself/him | |||

| 'Jan spoke on behalf of himself.' | ||||

| b. | Er | werd | gesproken [PP | namens hem/*zichzelf]. | passive | |

| there | was | spoken | on.behalf.of him/himself |

For the sake of completeness, note that our conclusion that Dutch zichzelf cannot function as a logophor but always behaves as an anaphor not only contradicts Reinhart & Reuland’s reformulation of the binding theory in (133). It also goes against proposals that aim to derive conditions A and B from specific theories of A-movement by saying that complex anaphors are actually the spell-out of A-movement traces in specific syntactic configurations; cf. e.g. Hornstein (2001) and Grohmann (2003). This would incorrectly predict that Dutch zichzelf cannot occur in positions from which A-movement is impossible, such as the adverbial PP in (140): example (141b) shows that the nominal argument of such adverbial phrases cannot be promoted to subject in passive constructions. In fact, the extraction of the nominal complement of namens is never possible, as shown by the contrast between Namens wie spreekt Jan? On behalf of whom does Jan speak and *Wie sprak Jan namens?

| a. | Jan spreekt [PP | namens | de familie]. | active | |

| Jan speaks | on.behalf.of | the family |

| b. | * | De familiei | werd [PP | namens ti] | gesproken. | passive |

| the family | was | on.behalf.of | spoken |

The prediction conflicts not only with examples such as (140), but also with examples such as (142a), in which zichzelf occurs as part of a PP-complement of the verb, because Dutch does not have so-called pseudo-passives of the kind in (142b').

| a. | Jan houdt [PP | van zichzelf] | PP-complement | |

| Jan loves | of himself | |||

| 'Jan loves himself.' | ||||

| b. | Jan houdt [PP | van Peter/hem]. | active | |

| Jan loves | of Peter/him | |||

| 'Jan loves Peter/him.' | ||||

| b'. | * | Peteri/Hiji | wordt [PP | van ti] | gehouden. | passive |

| Peter/ he | is | of | loved |

This section has shown that Reinhart & Reuland’s (1993) central claim that anaphors occur only in argument positions cannot be sustained, and that this poses a serious problem not only for their reflexivity framework, but also for approaches that aim to derive binding condition A by claiming that anaphors are the spell-out of A-movement traces. Therefore, we will set aside such theories in what follows.

Section 23.2, sub IIIA, has shown that possessive pronouns do not have a reflexive form, while there is a reciprocal form elkaarseach otherʼs; this is illustrated again in (143a). However, example (143b) shows that the desired “local” binding relation can be expressed with the referential possessive pronoun zijnhis.

| a. | Zij bewonderen | elkaars/*zichzelfs | werk. | |

| they admire | each.other’s/himself’s | work |

| b. | Jan bewondert | zijn/*zichzelfs | broer. | |

| Jan admires | his/himself’s | brother |

The examples in (143) are potentially problematic for classical binding theory: they show that the mutual exclusion of referential pronouns and anaphors should be seen as a property of personal pronouns only. That referential possessive pronouns are not mutually exclusive with possessive anaphors is clear: they can occur in the same position as reciprocal possessive pronouns, as shown in (144).

| a. | Zij | bezoeken | hun ouders. | |

| they | visit | their parents |

| b. | Zij | bezoeken | elkaars | ouders. | |

| they | visit | each.other’s | parents |

Furthermore, the fact that the mutual exclusion of referential pronouns and anaphors breaks down in the case of possessive pronouns should be seen as a language-specific property of Dutch (as well as English). Other languages do distinguish between reflexive and referential possessive pronouns, as illustrated for Swedish by the instances in (145), taken from Rooryck & Vanden Wyngaerd (2011:17). The possessive pronoun can only be bound by the subject honshe when it takes the reflexive form sin; cf. also Thráinsson (2007:484-5) and Reuland (2011).

| a. | Honi | älskar | sini/*j | man. | |

| she | loves | herreflexive | husband | ||

| 'She loves her (own) husband.' | |||||

| b. | Honi | älskar | hennesj/*i | man. | |

| she | loves | herreferential | husband | ||

| 'She loves her (someone else's) husband.' | |||||

The fact that the mutual exclusion of referential and reflexive personal pronouns does not apply to Dutch possessive pronouns might lead us to further reconsider the nature of the binding conditions of the classical binding theory in (146).

| a. | Anaphors are bound in their local domain. |

| b. | Referential pronouns are free in their local domain. |

| c. | Referential expressions are free. |

We have already seen in Section 23.2, sub IIA, that binding condition C can be reformulated as a kind of elsewhere principle, which states that a referential dependency must be expressed by a bound anaphor/pronoun whenever possible; this would imply that referential expressions can be used to express a referential dependency only in contexts that do not license binding (e.g. when there is no c-command relation between the referentially dependent phrases). A similar elsewhere principle can be formulated for binding condition B by saying that referential pronouns can be used to express a binding relation only when a reflexive form is not possible or available; cf. Rooryck & Vanden Wyngaerd (2011:§2.3) and the references cited there for relevant discussion. If we retain the formulation of condition A in (146a) that anaphors must be bound in their local domain, this would have the desired effect that referential pronouns can only be used to express a binding relation (i) when the intended antecedent is not in their local domain, or (ii) when the language in question does not have a specialized reflexive form (as in e.g. Frisian). Then case (i) would account for the mutual exclusion of referential and reflexive personal pronouns in languages that have them, while case (ii) would account for the fact that in Dutch referential possessive pronouns can occur in the same position as the reciprocal possessive pronoun elkaars, because there is no reflexive possessive pronoun *zichzelfs. This opens up the possibility of reducing the classical binding theory to (i) binding condition A and (ii) two additional elsewhere conditions, which can be translated into the following hierarchy proposed in Burzio (1991:93) and Safir (2004a/2004b).

| Hierarchy of choice for bound NPs: anaphor > pronoun > referential expression |

The hierarchy may be motivated by morphosyntactic considerations: for example, it is often claimed that anaphors have fewer specified morphosyntactic features for person, number and gender than referential pronouns, and referential pronouns certainly have fewer specified semantic features than referential expressions; cf. Reuland (2011) and Rooryck & Vanden Wyngaerd (2011:49). Together with independently motivated restrictions from pragmatics or discourse theory, this may lead to the specific order in (147).

Picture and story nouns are problematic for the presumed mutual exclusivity of referential pronouns and anaphors: it seems to break down when the referentially dependent element occurs in the complement of such nouns. This is illustrated in (148) for the picture noun fotophotograph. Under the assumption adopted so far that the minimal clause constitutes the local binding domain, condition A correctly predicts that (148a) is acceptable. Condition B, on the other hand, incorrectly predicts that (148b) with the weak pronoun ʼmhim would be unacceptable in the intended reading (but note that the intended reading is correctly ruled out for the strong pronoun hemhim).

| a. | Jan | zag | een foto | van zichzelf. | |

| Jan | saw | a picture | of himself | ||

| 'Jan saw a picture of himself.' | |||||

| b. | Jan | zag | een foto | van ’m. | |

| Jan | saw | a picture | of him | ||

| 'Jan saw a picture of himself.' | |||||

One solution to this problem appeals to the semantic intuition that picture and story nouns have an argument structure, in that they can take a “theme” argument referring to the object depicted and an “agentive” argument referring to the creator of the referent of the whole noun phrase; cf. mijnagent foto van Jantheme my picture of John. The examples in (149) show that the overt realization of such agentive arguments as a prenominal possessor can affect the available binding relations: anaphors in the complement of the noun must be bound by the possessor; pronouns, on the other hand, cannot be bound by the possessor, while they can be bound by the subject of the clause (or refer to some other referent in the domain of discourse).

| a. | Ik | zag | Jans foto | van | zichzelf/*’m. | |

| I | saw | his picture | of | himself/him | ||

| 'I saw his picture of himself.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan | zag | mijn foto | van ’m/*zichzelf. | |

| Jan | saw | my picture | of him/himself | ||

| 'Jan saw my picture of him.' | |||||

Chomsky (1986) has argued that examples such as (148) can now be accounted for by assuming that they contain a phonetically unrealized agent, which we have indicated by means of PRO in the representations in (150). Assuming that PRO can be accidentally coreferential with the subject of the clause, which is indicated by coindexation, we expect an anaphor to be interpreted as coreferential with the subject of the clause (by transitivity). If PRO refers to some other (possibly arbitrary) person, ʼm but not zichzelf can be interpreted as coreferential with the subject of the clause for the same reason as in (149b). This shows that the lack of mutual exclusivity in the examples in (148) is only an illusion.

| a. | Jani zag [NP een PROi foto van zichzelf/*’m]. |

| b. | Jani zag [NP een PROarb foto van ’m/*zichzelf]. |

The presence of an implicit argument PRO can be independently motivated by the fact that its interpretation can be affected by the context. An illustrative case is een foto nemen van in its more or less idiomatic reading “to take a picture of”, which implies that the subject is the creator of the picture, i.e. the indexation in (151a) is the only possible option.

| a. | Jani nam [NP een PROi foto van Peter]. |

| b. | * | Jani nam [NP een PROarb foto van Peter]. |

This entails that a referentially dependent element in the complement of the noun can only be an anaphor, as in (152a): coreference between the subject and the pronoun ʼmhim would lead to a violation of binding condition B by transitivity: the referential pronoun ʼm is incorrectly bound by PRO.

| a. | Jani nam [NP een PROi foto van zichzelf]. |

| b. | * | Jani nam [NP een PROi foto van ’m]. |

Note in passing that the discussion of (151/152) suggests that a better analysis for (148a) might be that PRO is absent and the binding relation between Jan and zichzelf is established directly; cf. Jan zag [NP een foto van zichzelf]. This analysis (which Chomsky explicitly left open) might be more adequate, since representation (150a) should express that Jan saw one of his own selfies, which is of course not an entailment of (148a). We will not digress on this issue here but refer the reader to Section 16.2.5.2 for a more detailed discussion.

The presence of an implicit PRO argument can also be motivated by the (relative) acceptability of the examples in (153), where an anaphor is embedded in a subject headed by a picture noun. If the structures were as indicated here, we would be dealing with a violation of binding condition A, as the anaphor is bound by a noun phrase external to its local domain (i.e. its minimal clause).

| a. | ? | [Jan en Marie]i | dachten | dat | er | [foto’s van zichzelfi] | te koop | waren. |

| Jan and Marie | thought | that | there | pictures of themselves | for sale | were | ||

| 'Jan and Marie thought that pictures of themselves were on sale.' | ||||||||

| b. | ? | [Jan en Marie]i | dachten | dat | er | [foto’s van elkaari] | te koop | waren. |

| Jan and Marie | thought | that | there | pictures of each.other | for sale | were | ||

| 'Jan and Marie thought that pictures of each other were on sale.' | ||||||||

However, if the picture noun contains an agentive PRO argument, the referential dependency can be established indirectly: the anaphor can be bound by PRO according to binding condition A, and PRO in turn can be construed as coreferential with the subject of the matrix clause. A potential problem is that the claim that PRO is an agent again predicts that the subject of the matrix clause refers to the creators of the pictures in question, but it is not so clear whether this is actually implied by these examples. Again, we refer the reader to Section 16.2.5.2 for a more detailed discussion of examples of the kind in (153), which also addresses questions about their (presumed) grammaticality.

This section has shown that the possible counterexamples to the supposed mutual exclusion of referential personal pronouns and anaphors in (148) receive a natural explanation if we assume that the “agentive” argument of picture nouns can be syntactically present but phonetically empty. We have also seen in passing that the local domain mentioned in the binding conditions can be smaller than the minimal clause containing the referential pronoun or anaphor; in example (149) the local domain is the minimal noun phrase containing these elements. This shows that our initial definition of the notion of local domain needs to be revised; this will be the main topic of Subsection II.

We have so far tentatively assumed that the anaphoric domain in which an anaphor (i.e. reflexive/reciprocal pronoun) must be bound and a referential pronoun must be free is its minimal clause. However, Subsection IC has shown that the anaphoric domain can sometimes be smaller, viz. the minimal noun phrase of the pronoun. This shows that we cannot designate a specific categorial type of constituent, such as clause, as the anaphoric domain, but that we must find some other defining property. The following subsections will show that the notion of complete functional complex comes close to the mark (Subsection A), although it still leaves one specific context unexplained (Subsection B).

Subsection IC has shown that the notion of local domain in the sense of binding conditions A and B cannot be characterized as being of a specific categorial type such as clause. This means that we have to find some other definition of the various anaphoric domains relevant for binding theory (minimal clause, noun phrase, etc.). This subsection will show that Chomsky’s (1986) notion of complete functional complex is quite adequate.

Let u provisionally s assume that the minimal projection in which all the arguments of a main verb are realized is the clause headed by the verb. This is illustrated in example (155), in which the CFC of the verb zien is surrounded by square brackets. The examples show again that while anaphors must be bound, referential pronouns must be free in this anaphoric domain.

| Complete functional complex (CFC): The minimal projection of a lexical head H in which all its arguments are realized. |

| a. | Peter denkt [clause | dat | Jan zichzelf/*hem | (in de spiegel) | ziet]. | |

| Peter thinks | that | Jan himself/him | (in the mirror) | sees |

| a'. | Peter denkt [clause | dat Jan *zichzelf/hem (in de spiegel) ziet]. |

| b. | Peter denkt [clause | dat | Jan alleen | van zichzelf/*hem | houdt]. | |

| Peter thinks | that | Jan only | of himself/him | loves |

| b'. | Peter denkt [clause dat Jan alleen van *zichzelf/hem houdt]. |

| c. | Peter denkt [clause | dat | Jan trots | op zichzelf/*hem | is]. | |

| Peter thinks | that | Jan proud | on himself/him | is |

| c'. | Peter denkt [clause dat Jan trots op *zichzelf/hem is]. |

The notion of CFC is also relevant for lexical heads other than verbs. Example (156) illustrates this for the adjective verliefdin love. This adjective takes an (optional) PP-complement op NP, and the resulting complex predicate verliefd op NP is predicated of the noun phrase Jan. The CFC is thus the phrase in square brackets, known in generative grammar as a small clause (SC): in the (a)-examples the logical subject of the small clause, Jan, is assigned objective case by the main verb achtento consider, while in (156b) it is moved into the subject position of the sentence (hence the trace t), where it is assigned nominative case. The crucial point for our present discussion is that the anaphor zichzelf must, but the referential pronoun hem cannot be bound by the logical subject of the small clause in (156a&b). Furthermore, hem can be bound by the subject of the sentence in (156a'), whereas this is impossible for zichzelf.

| a. | Peter acht [SC | Jan | verliefd | op zichzelf/*hem]. | |

| Peter considers | Jan | in-love | on himself/him | ||

| 'Peter believes Jan to be in love with himself.' | |||||

| a'. | Peter acht [SC | Jan verliefd | op *zichzelf/hem]. | |

| Peter considers | Jan in-love | on himself/him | ||

| 'Peter believes Jan to be in love with him.' | ||||

| b. | Jani | is [SC ti | verliefd | op zichzelf/*hem]. | |

| Jan | is | in-love | on himself/him | ||

| 'Jan is in love with himself.' | |||||

The examples in (157) show essentially the same thing for the locational adposition bijnear. This adposition takes a nominal complement and the resulting complex predicate bij NP is predicated of the noun phrase de hondenthe dogs. The CFC of the adposition is therefore the prepositional small clause in square brackets: in the (a)-example the logical subject of the small clause, de hondenthe dogs, is assigned objective case by the main verb vindento consider, while in (157b) it is moved into the subject position of the sentence, where it is assigned nominative case. The crucial observation for our present discussion is that in (157a&b) the anaphor elkaar must, but the referential pronoun zethem cannot be bound by the logical subject of the small clause, de honden. Furthermore, in (157a') the referential object pronoun ze can be bound by the subject of the sentence, whereas this is impossible for elkaar. Note in passing that in (157a') the simplex reflexive zich would normally be preferred; we will ignore this issue for now, but return to it in Section 23.4.

| a. | De kinderen | houden [SC | de honden | bij elkaar/*ze]. | |

| the children | keep | the dogs | with each.other/them | ||

| 'The children keep the dogs together.' | |||||

| a'. | De kinderen | houden [SC | de honden | bij *elkaar/ze]. | |

| the children | keep | the dogs | with each.other/them | ||

| 'The children keep the dogs with them.' | |||||

| b. | De hondeni | liggen [SC ti | bij elkaar/*ze]. | |

| the dogs | lie | with each.other/them | ||

| 'The dogs lie together.' | ||||

The examples in (158) again show the same thing for a nominal small clause: the voor-PP is a complement of the noun probleem, and the phrase een probleem voor NP (we will ignore the obligatory article een in our present discussion) is predicated of the noun phrase Jan. The CFC of the noun is therefore the nominal small clause in square brackets: in the (a)-example the logical subject of the small clause is assigned objective case by the verb vindento consider, while in (158b) it is moved into the subject position of the sentence, where it is assigned nominative case. The crucial point for our present purpose is that in (158a&b) the anaphor zichzelf must, but the referential pronoun hemhim cannot be bound by the logical subject of the small clause Jan. Furthermore, in (158a') hem can be bound by the subject of the sentence in (156a), whereas this is impossible for zichzelf.

| a. | Peter vindt [SC | Jan een probleem | voor zichzelf/*hem]. | |

| Peter considers | Jan a problem | for himself/him | ||

| 'Peter believes Jan to be a problem for himself.' | ||||

| a'. | Peter vindt [SC | Jan een probleem | voor *zichzelf/hem]. | |

| Peter considers | Jan a problem | for himself/him | ||

| 'Peter believes Jan to be a problem for him.' | ||||

| b. | Jani | is [SC ti | een probleem | voor zichzelf/*hem]. | |

| Jan | is | a problem | for himself/him | ||

| 'Peter believes Jan to be a problem for himself.' | |||||

Finally, consider the so-called accusativus-cum-infinitivo (AcI) constructions in (159). Although it is not generally done this way, we can describe the construction, just like the cases above, in terms of a small-clause analysis: the infinitival main verb schieten takes a PP-complement, and the resulting phrase op zichzelf schieten is predicated of Jan; the bare infinitival clause is therefore a CFC. Crucially, the anaphor zichzelf must, but the referential pronoun hemhim cannot be bound by the logical subject of the infinitival clause Jan. Furthermore, hem can be bound by the subject of the matrix clause, whereas this is impossible for zichzelf. Example (159b) is a so-called subject-raising construction in which the logical subject of the infinitival clause is realized as the subject of the matrix clause; as expected, the anaphor zichzelf, but not the referential pronoun hem, can be bound by the raised subject. See Section V5.2 for a discussion of the distribution of the infinitival marker te in these examples.

| a. | Peter zag [Clause | Jan op zichzelf/*hem | schieten]. | |

| Peter saw | Jan at himself/him | shoot | ||

| 'Peter saw Jan shoot at himself.' | ||||

| a'. | Peter zag [Clause | Jan op *zichzelf/hem schieten]. | |

| Peter saw | Jan at himself/him shoot | ||

| 'Peter saw Jan shoot at him.' | |||

| b. | Jani leek [Clause ti | op zichzelf/*hem | te schieten]. | |

| Jan appeared | at himself/him | to shoot | ||

| 'Jan appeared to shoot at himself.' | ||||

Note that (159) shows that our tentative assumption that the CFC of a main verb is the whole clause it heads is not entirely correct: we can simply define the CFC of a main verb as its lexical projection, to the exclusion of the functional part of the clause expressing finiteness; cf. Section V9.1 for details. Excluding the functional part of the clause expressing finiteness is not a trivial matter, though, as we will see in Subsection B, finiteness has its own role to play in defining the anaphoric domain.

Subsection A has shown that defining anaphoric domains in terms of complex functional complexes (CFCs) is a major improvement because it extends the empirical coverage of binding theory. However, this subsection will show that there is still one specific case that is not covered by this definition of anaphoric domain. The examples in the previous subsection concerned referential pronouns and anaphors (embedded in a phrase) functioning as a complement of the lexical head of the CFC: anaphors must be bound by the logical subject of the CFC. This section discusses the binding behavior of the logical SUBJECT of the CFC itself. Consider the cases in (160), in which the CFCs are again indicated by square brackets.

| a. | Peter acht [SC | zichzelf/*hem | verliefd | op Jan]. | adjectival SC | |

| Peter considers | himself/him | in-love | on Jan | |||

| 'Peter believes himself to be in love with Jan.' | ||||||

| b. | Zij | gooiden [SC | elkaar/*hen | in het water]. | adpositional SC | |

| they | threw | each.other/them | into the water | |||

| 'They threw each other into the water.' | ||||||

| c. | Jan vindt [SC | zichzelf/*hem | een bekwaam taalkundige]. | nominal SC | |

| Jan considers | himself/him | a competent linguist | |||

| 'Jan believes himself to be a competent linguist.' | |||||

| d. | In zijn droom | zag | Jan [SC | zichzelf/*hem | op Peter | schieten]. | verbal SC | |

| in his dream | saw | Jan | himself/him | at Peter | shoot | |||

| 'In his dream, Jan saw himself shooting at Peter.' | ||||||||

The examples show that a logical subject of a CFC can be bound by the subject of the sentence when it is an anaphor, but not when it is a pronoun. This makes it clear that it is not the CFC of the small clause that functions as an anaphoric domain for its logical subject, but the minimal clause that embeds it. The reason for this is that the logical subject is not only part of the CFC but also of the matrix clause, in which it performs the grammatical function of direct object in the sense that it is assigned accusative case by the verb. This becomes clear when we consider the behavior of logical subjects of small clauses under passivization of the verb in (161): the logical subject of the small clause becomes the subject of the clause, just like a regular direct object (i.e. a nominal theme argument of the verb). Note that we did not include a passive example of the AcI-construction in (160d): such constructions cannot be passivized for some independent reason.

| a. | Ik | vind [SC | Jan/hem | aardig]. | |

| I | consider | Jan/him | nice |

| a'. | Jani/hiji | wordt [SC ti | aardig] | gevonden. | |

| Jan/he | is | nice | considered |

| b. | Ik | acht [SC | Marie/haar | een bekwaam taalkundige]. | |

| I | consider | Marie/her | a competent linguist |

| b'. | Mariei/ziji | wordt [SC ti | een bekwaam taalkundige] | geacht. | |

| Marie/she | is | a competent linguist | considered |

| c. | Jan houdt [SC | de honden/hen | bij elkaar]. | |

| Jan keeps | the dogs/them | with each.other | ||

| 'Jan keeps the dogs/them together.' | ||||

| c'. | De hondeni/ziji | worden [SC ti | bij elkaar] | gehouden. | |

| the dogs/they | are | with each.other | kept |

We can account for the special behavior of the logical subject of a CFC with respect to binding by defining the notion of anaphoric domain as in (162): see Vat (1980), Everaert (1986), and Broekhuis (1987/1992) for various implementations of the general idea that both selection (i.e. semantic licensing) and case marking (i.e. formal licensing) play a role in defining anaphoric domains. We will assume that selection is the structural relation between a HS(emantic) and its internal arguments (i.e. its complements, to which it assigns a thematic role); the logical subject of a small clause is therefore not selected by HS. We will further assume that HC(ase) can assign case directly or indirectly with the help of a so-called functional preposition selected by it, as in schieten op to shoot at and verliefd op in love with.

| Anaphoric domains of noun phrase α: The minimal CFC containing: |

| i. | a lexical head HS selecting (i.e. assigning a thematic role to) α, and/or; | ||

| ii. | a lexical head HC formally licensing (i.e. assigning case to) α. |

In the cases in (156) to (159) from Subsection A, the two subclauses in (162) have the same result because the lexical head H functions both as HS and HC; (i) the anaphor/referential pronoun is assigned a thematic role by H, and (ii) it is also assigned case either directly by H or by the functional preposition H selects. The subclauses in (162) thus both define the whole small clause as the relevant anaphoric domain in which the anaphor/referential pronoun must be bound/free. In (160), on the other hand, the anaphor/referential pronoun is a logical subject, which is not selected by the head of the small clause in the technical sense indicated above. The anaphoric domain of the pronoun is therefore computed on the basis of (162ii) alone: the logical subject of the small clause is assigned case by the main verb, and its anaphoric domain is therefore the CFC of the main verb. This correctly predicts that the logical subject of the small clause can be bound by the subject of the clauses in (160) if it is an anaphor, but not if it is a pronoun.

Note that the element assigning case to the anaphor/referential pronoun in the examples in (160) is the lexical head of the next higher CFC. This may be relevant to the acceptability judgments on the data in (163).

| Jan zei | dat | hij/*zichzelf | morgen | komt. | ||

| Jan said | that | he/himself | tomorrow | comes |

We adopt the standard assumption that nominative case is assigned by the functional element tense expressing finiteness, which is external to the lexical projection of the main verb. If the anaphoric domain of the subject of the embedded clause were the minimal CFC containing its case-assigner, we would predict that the subject of the matrix clause in (163) can act as an antecedent for the anaphor zichzelf, but not for the referential subject pronoun hijhe; however, the attested pattern is the other way around. The requirement in (162) that the case-assigner must be lexical (i.e. able to project its own CFC), on the other hand, has the desired result: the subject of a finite clause has no anaphoric domain, so that binding condition A (an anaphor must be bound in its anaphoric domain) simply cannot be met, and condition B (a referential pronoun must be free in its anaphoric domain) is trivially satisfied.

More can be said about referentially dependent elements functioning as the logical subject of CFCs; we will return to this issue in Section 23.4.1, sub III, where we will show that it is also possible to use the simplex reflexive zich in this position. Finally, we would like to refer the reader to Reinhart & Reuland (1993:§6) and Reuland (2011:§3) for an alternative account of the contrasts in (160), according to which the simplex/complex anaphors and referential pronouns are all acceptable in the subject position of a small clause as far as the binding conditions are concerned, but bound referential pronouns are prohibited by a special condition on A-chains.

The notion CFC corresponds more or less to the semantic notion of proposition. This is relevant in view of the fact established earlier that an anaphor embedded in an adpositional adverbial phrase can be bound by an antecedent external to its minimal PP. In other words, adverbial PPs are modifiers and therefore do not count as CFCs. Since the adposition assigns case (and possibly also a thematic role) to its complement, we correctly predict that anaphors embedded in adverbial phrases can have an antecedent in the minimal CFC that contains them.

The original definition of anaphoric domain in Chomsky (1981) was relatively technical and relied heavily on technical notions that were abandoned in the minimalist version of the theory proposed in Chomsky (1995a:§3). The definition adopted here, based on Chomsky (1986), relies essentially on notions that are still available, namely lexical (or propositional) domain of a head and case assignment. This means that there is no a priori reason to assume that it cannot find a proper place in the current minimalist version(s) of generative grammar. Classical binding theory is quite successful in describing the distribution of complex reflexive and reciprocal personal pronouns, once the notion of anaphoric domain is properly formulated. However, Section 23.4 will show that new and intricate problems arise when we apply this theory to languages with simplex reflexive personal pronouns, such as Dutch zich, which cannot be easily explained by an appeal to classical binding theory.