- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This section looks at existential quantifiers like sommigesome and enkelesome. Subsection I begins with a discussion of their use as modifiers of the noun phrase. Subsection II continues with their use as arguments; existential quantifiers cannot be used as floating quantifiers and cannot be modified.

This subsection will look at the use of existential quantifiers like sommigesome and enkelesome as modifiers of a noun phrase. These quantifiers are existential in the sense that examples such as (217) express that the set denoted by the VP op straat lopento walk in the street includes a number of boys.

| a. | Sommige jongens | lopen | op straat. | |

| some boys | walk | in the.street | ||

| 'Some boys walk in the street.' | ||||

| b. | Er | lopen | enkele jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | sm boys | in the.street | ||

| 'Some boys walk in the street.' | |||||

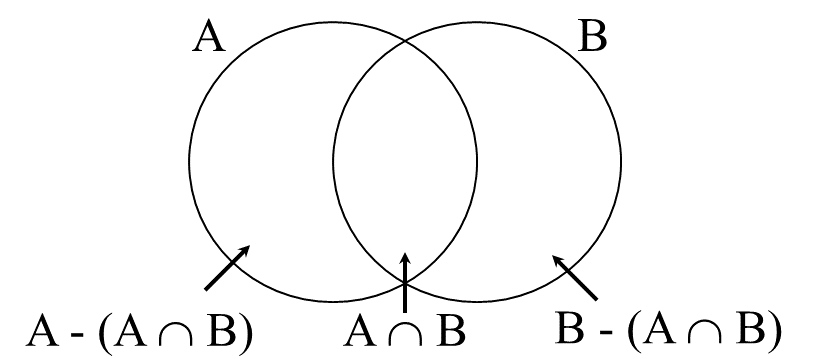

Although the translations in (217a&b) are the same, there is a clear difference between the two examples. The noun phrase in (217a) refers to a subset of the boys in a given discourse domain D. In terms of Figure 1, repeated below, this means that it expresses that the intersection of the set of boys (set A) and the set of entities walking in the street (set B) is non-empty: A ∩ B ≠ ∅. Example (217b), on the other hand, does not refer to a contextually determined set of boys in domain D, but instead introduces some boys into domain D who are said to be walking in the street, which also results in A ∩ B ≠ ∅.

It is often claimed that the existential quantifiers sommige and enkele express not only that the intersection A ∩ B is non-empty, but also that the cardinality of the intersection is higher than 1, but still quite small with respect to the size of the contextually determined set A. It is not clear a priori whether all this is actually part of the lexical meaning of the quantifier. If the earlier assumption in Section 19.1.1.1 that the plural marking on the noun expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 is correct, then the implication in (217) that |A ∩ B| > 1 may indeed be due to the presence of the quantifier. However, the fact that the cardinality is construed as rather low may be the result of a conversational implicature: since the speaker can use a high-degree quantifier to express that the cardinality is high, the absence of such a high-degree quantifier suggests that the cardinality is only moderate (Grice’s maxim of quantity). For the moment, we will leave this issue as it is and assume that the existential quantifiers simply express that the cardinality of the intersection A ∩ B is greater than 1.

The quantifiers enkele and sommige (on their non-D-linked reading) are weak and strong noun phrases, respectively. Section 20.2.1 has already shown that strong quantifiers like sommige cannot occur in existential constructions with the expletive erthere, while weak quantifiers like enkele can; this is illustrated by the slightly extended version of (217) in (218).

| a. | Enkele/Sommige jongens | lopen | op straat. | |

| some/some boys | walk | in the.street | ||

| 'Some boys walk in the street.' | ||||

| b. | Er | lopen | enkele/*sommige jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | sm/some boys | in the.street | ||

| 'Some boys walk in the street.' | |||||

Another difference seems to be that, unlike at least some weak quantifiers, strong quantifiers cannot occur in nominal measure phrases; cf. example (219).

| a. | Dat boek | kost | enkele/*sommige | tientjes. | |

| that book | costs | sm/some | tenners |

| b. | De schat | ligt | enkele/*sommige meters | onder de grond. | |

| the treasure | lies | sm/some meters | under the ground |

| c. | Marie heeft | enkele/*sommige jaren | in Berlijn | gewoond. | |

| Marie has | sm/some years | in Berlin | lived |

The primeless examples in (220) show that universal quantifiers can be used neither in expletive er constructions nor in nominal measure phrases, so that they must also be considered as strong quantifiers. In other words, universal quantifiers like alleall or elkeach form a natural class with the strong existential quantifier sommige. The weak existential quantifier enkele, on the other hand, forms a natural class with the cardinal numerals, which can also occur in expletive er constructions, as shown in the primed examples.

| a. | * | Er | lopen | alle jongens | op straat. |

| there | walk | all boys | in the.street |

| a'. | Er | lopen | vijf jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | five boys | in the.street |

| b. | * | Dat boek | kost | alle tientjes. |

| that book | costs | all tenners |

| b'. | Dat boek | kost | drie tientjes. | |

| that book | costs | three tenners |

Note that the distinction between weak and strong quantifiers is not absolute. We have seen in example (218a) that the quantifier enkele can also be used as a strong quantifier, in which case it does not introduce new entities into domain D, but simply quantifies over a contextually determined set of entities within domain D; we will return to this shortly.

The examples in (218) express that the cardinality of the set of boys walking in the street is greater than 1; the quantified noun phrases sommige jongens and enkele jongens thus seem to behave as plural counterparts of the noun phrases in (221a&b) introduced by the indefinite article eena (note that een must be stressed in (221a), so we cannot rule out the possibility that we are dealing with the numeral éénone in this example). Therefore, it would be justified to treat the indefinite article in this subsection as well, but since this element is discussed in Section 19.1, we will refrain from doing so. The same applies to the negative article/quantifier geenno in (221c), which can be considered a negative existential quantifier (¬∃x).

| a. | Eén jongen | loopt | op straat. | |

| a/one boy | walks | in the.street |

| b. | Er | loopt | een jongen | op straat. | |

| there | walks | a boy | in the.street |

| c. | Er | loopt | geen jongen | op straat. | |

| there | walks | no boy | in the.street |

The remainder of this subsection discusses different types of existential quantifiers in more detail. In the course of the discussion, we will see that the distinction between existential and degree quantifiers like veelmany/much and weinigfew/little is not always clear-cut.

The most common existential quantifiers are enkele and sommige. We have already seen that the two differ in that the former can be weak or strong, while the latter is necessarily strong. That enkele can be a weak quantifier is illustrated again in the examples in (222), where enkele is used as a modifier of a subject. Under neutral intonation, the clause preferably takes the form of an expletive er construction, as in (222a); example (222b) is usually pronounced with emphatic focus accent on the quantifier. The two examples differ in interpretation: in (222a) the subject introduces new entities into domain D, while in (222b) the subject has a partitive reading; domain D already includes a set of boys, and the sentence expresses that some of these boys are walking in the street.

| a. | Er | lopen | enkele jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | sm boys | in the.street | ||

| 'There are some boys walking in the street.' | |||||

| b. | Enkele/?Enkele | jongens | lopen | op straat. | |

| some | boys | walk | in the.street | ||

| 'Some (of the) boys are walking in the street.' | |||||

That the quantifier sommige is necessarily strong is clear from the fact that the expletive er construction in (223b) is impossible. This quantifier therefore cannot be used to introduce new discourse entities, but quantifies over a pre-established set of boys in domain D.

| a. | Sommige jongens | lopen | op straat. | |

| some boys | walk | in the.street | ||

| 'Some boys walk in the street.' | ||||

| b. | * | Er | lopen | sommige jongens | op straat. |

| there | walk | some boys | in the.street |

Another existential quantifier that is quite common is watsome. This quantifier is clearly weak, as shown by the fact that only the expletive er construction is acceptable in (224); the (b)-example cannot be remedied by assigning emphatic accent to the quantifier.

| a. | Er | lopen | wat jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | some boys | in the.street | ||

| 'There are some boys walking in the street.' | |||||

| b. | * | Wat jongens | lopen | op straat. |

| some boys | walk | in the.street |

A striking difference between wat and enkele/sommige is that the former can easily be used as a modifier of non-count nouns, whereas the latter usually cannot. This is shown in (225).

| a. | Ik | heb | wat bier | gekocht. | |

| I | have | some beer | bought |

| b. | * | Ik | heb | enkele/sommige bier | gekocht. |

| I | have | sm/some beer | bought |

Haeseryn et al. (1997:370) claims that in contrastive contexts sommig(e) can be combined with substance nouns like bierbeer with a “kind” interpretation, as in (226a). Although we have indeed found a small number of such cases on the internet, they strike us as distinctly odd; we much prefer the use of the plural form sommige bieren in (226b), in which case we are clearly dealing with a count noun.

| a. | % | Sommig bier | heeft | een bittere nasmaak. |

| some beer | has | a bitter aftertaste |

| b. | Sommige bieren | hebben | een bittere nasmaak. | |

| some beers | have | a bitter aftertaste |

Since the ability to act as a modifier of a non-count noun is also a property of degree modifiers such as veelmany/much discussed in Section 20.2.4, it might be the case that wat in (225) functions not as an existential quantifier but as a degree quantifier. Such a view could be supported by the fact that, unlike enkele and sommige, wat can be modified by degree modifiers like nogal, tamelijk, heel, aardig. This is illustrated in (227), where the cardinality of the set denoted by boeken is indeed compared to an implicit norm.

| a. | Jan heeft | nogal/heel/aardig | wat boeken. | |

| Jan has | quite/very/quite | some books | ||

| 'Jan has quite a few books.' | ||||

| b. | * | Jan heeft | nogal/heel/aardig | enkele/sommige boeken. |

| Jan has | quite/very/quite | some books |

Besides the existential quantifiers discussed above, Dutch has many other formatives that can be used in a similar way. We will briefly discuss some of these formatives, starting with some simple forms and ending with some phrase-like forms.

Example (228a) shows that the form enige, which is used in more formal contexts, is a weak quantifier. Example (228b) shows that it differs from enkele in that it can be combined with non-count nouns. In this respect, it resembles wat, from which it differs in that it does not allow degree modification; cf. (228c).

| a. | Er | liggen | enige/enkele boeken | op de tafel. | |

| there | lie | sm/sm books | on the table |

| b. | Enige/*enkele tijd geleden | was | ik | ziek. | |

| some/some time ago | was | I | ill |

| c. | nogal/heel/aardig | wat/*enige boeken | |

| quite/very/quite | some/some books |

The examples in (229) show that enige can also be used as the equivalent of English any, as in (229a), or as an attributive adjective corresponding to “only” or “cute”; cf. Haeseryn et al. (1997:366ff.). The ambiguity of (229c) can be resolved by using the superlative form enigst in (229c'); although there is normative pressure not to use this form, it is often used with the meaning “only”; cf. also taaladvies.net/enigste-of-enige/ and onzetaal.nl/taalloket/enigst-kind-enig-kind.php.

| a. | Heb | je | wel | enig benul | van | wat | dat | kost? | |

| have | you | prt. | any idea | of | what | that | costs | ||

| 'Do you have any idea of what that costs?' | |||||||||

| b. | Dat | is de enige oplossing. | |

| that | is the only solution |

| c. | Hij | is | een enig kind. | |

| he | is | a cute/only child |

| c'. | Hij | is | een enigst kind. | |

| he | is | an only child |

The quantifiers verscheidene/meerderevarious, verschillendeseveral, and ettelijkea number of in (230) can be used as either weak or strong quantifiers. These quantifiers are always followed by a plural noun and tend to be used when the cardinality of the relevant set is somewhat higher than 2. For this reason, it is not so clear whether these quantifiers should be considered existential quantifiers: they might as well be degree quantifiers.

| a. | Er | liggen | verscheidene/verschillende/ettelijke/meerdere | boeken | op de tafel. | |

| there | lie | various/several/a.number.of/several | books | on the table | ||

| 'Various/several/a number of books are lying on the table.' | ||||||

| b. | Verscheidene/Verschillende/Ettelijke/Meerdere | boeken | waren | afgeprijsd. | |

| various/several/a.number.of/several | books | were | prt.-priced | ||

| 'Various/Several/A number of/Several books were reduced.' | |||||

The quantifier verschillende in (230) suggests that the entities in the relevant set of books are of different kinds. This is even clearer in the case of allerlei/allerhandeall kinds/sorts of in (231), which can only be used if the relevant set contains different categories of books like novels, books of poetry, textbooks, etc. Allerhande is also used as a noun meaning “assorted (luxury) cookies”.

| Er | liggen | allerlei/allerhande boeken | op de tafel. | ||

| there | lie | all sorts of books | on the table | ||

| 'All sorts of books are lying on the table.' | |||||

Finally, note that verschillende can also be used with the meaning “different”, in which case it clearly functions as an attributive adjective, as shown by the fact that in this use it can be modified by a degree adverb and used in predicative position.

| a. | Dit | zijn | twee totaal verschillende opvattingen. | |

| this | are | two completely different opinions |

| b. | Deze twee opvattingen | zijn | totaal verschillend. | |

| these two opinions | are | totally different |

The last simple form we will discuss here is menig(e)many. This form is typically used in writing and can only be used with singular count nouns. Like the quantifiers discussed in the previous subsection, menig(e) tends to be used when the cardinality of the relevant set is somewhat higher than 2, and for this reason it should perhaps be considered a degree quantifier. The uninflected form menig is used with het-nouns and optionally with some [+human] de-nouns, especially with manman, persoonperson, and nouns denoting professions. In all other cases the inflected form menige is used.

| a. | menig | boek | +neuter | |

| many | book |

| b. | menig(‑e) | arts | -neuter, person name | |

| many | physician |

| c. | menig*(‑e) | roman | -neuter | |

| many | novel |

According to our judgments on the examples in (234), the quantifier menig is strong; it is preferably D-linked, as in (234a), and thus quantifies over a presupposed set in domain D. Examples such as (234b) sound marked, although it should be noted that the example improves considerably when the sentence contains an adverbial phrase like alalready: Er werd al menig staker ontslagenThere were already many strikers fired. Because similar examples can easily be found on the internet (a search for the string [er werd menig] yielded over 100 hits), we conclude that, at least for some speakers, noun phrases containing menig can also be weak.

| a. | Menig staker | werd | ontslagen. | |

| many striker | was | fired | ||

| 'Many a striker was fired.' | ||||

| b. | ? | Er | werd | menig staker | ontslagen. |

| there | was | many striker | fired |

Noun phrases modified by the strong quantifier menig can easily be used in “generic” statements, i.e. in contexts where menig quantifies over all relevant entities in the speaker’s conception of the universe. This is illustrated in (235).

| Menig werknemer | is ontevreden | over zijn salaris. | ||

| many employee | is dissatisfied | with his salary | ||

| 'Many employees are not satisfied with their salaries.' | ||||

Besides the simplex forms mentioned above, there are several phrasal or phrase-like constructions that seem to act as existential modifiers. Some examples are given in (236). Binominal constructions such as those in (236a) are discussed in detail in Section 18.1.1, to which we refer for more information. The phrase-like forms deze of gene and één of andere can be paraphrased as “some”: the former seems to behave like a strong quantifier, while the latter is preferably used as a weak quantifier.

| a. | een paar | schoenen | |

| a couple [of] | shoes |

| b. | Deze of gene | specialist moet | toch | kunnen helpen. | |

| this or yonder | specialist must | prt | be.able help | ||

| 'But some specialist must be able to help.' | |||||

| b'. | * | Er | moet | deze of gene | specialist | toch | kunnen helpen. |

| there | must | this or yonder | specialist | prt | be.able help |

| c. | Er | loopt | één of andere hond | voor ons huis. | |

| there | walks | one or another dog | in.front.of our house | ||

| 'There is some dog walking in front of our house.' | |||||

| c'. | *? | Eén of andere hond | loopt | voor ons huis. |

| one or another dog | walks | in.front.of our house |

Despite its quantificational meaning, deze of gene in (236b) is probably best regarded as a complex determiner: if it were a determiner comparable to simple deze, its strong nature would follow immediately. The examples in (237a&b) show that a similar approach is clearly not feasible for één of ander, since this modifier can be preceded by a definite article. Despite being formally definite, the noun phrases de een of andere gek and het een of andere boek behave like weak noun phrases, just like their formally indefinite counterparts in the primed examples; they can all enter the expletive er construction. The (b)-examples in (237) suggest that we are dealing with a complex adjectival phrase: like adjectival anderdifferent, the phrase een of ander can be suffixed with the attributive -e ending.

| a. | Er | staat | de een of andere gek | te zingen. | definite, neuter | |

| there | stands | the one or other maniac | to sing | |||

| 'There is some madman singing.' | ||||||

| a'. | Er | staat | een of andere gek | te zingen. | indefinite, neuter | |

| there | stands | one or other maniac | to sing | |||

| 'There is some madman knocking on the door.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | werd | het een of andere boek | gepresenteerd. | definite, +neuter | |

| there | was | the one or other book | presented | |||

| 'Some book was presented.' | ||||||

| b'. | Er | werd | een of ander boek | gepresenteerd. | indefinite, +neuter | |

| there | was | one or other book | presented | |||

| 'Some book was presented.' | ||||||

Finally, we should mention cases such as de nodige bezwarena good many objections. This is clearly a borderline case. The noun phrase is formally a definite noun phrase, and nodige seems to function as a regular attributive adjective. However, the noun phrase does not refer to entities in domain D, and again it can be used in the expletive er construction.

| Er | werden | de nodige bezwaren | geopperd. | ||

| there | were | the need objections | given | ||

| 'A good many objections were raised.' | |||||

Note that the translation in (238) is somewhat misleading in that it suggests that a fairly large number of objections were raised, but this is not necessarily true; what is implied is that the number of objections was sufficiently large to be relevant.

This subsection concludes the discussion of existential quantifiers in their use as modifiers with two special uses of sommige and enkele.

The quantifier sommige is sometimes used in “generic” contexts, i.e. to quantify over all relevant entities in the speaker’s conception of the universe: for instance, an example such as (239a) expresses that there is a subcategory of junkies who will never overcome their addiction. Such a “generic” use is not possible with enkele: in example (239b), the quantifier enkele must quantify over a contextually defined set of junkies.

| a. | Sommige junkies | komen | nooit | van hun verslaving | af. | |

| some junkies | come | never | from their addiction | prt. | ||

| 'Some junkies will never overcome their addiction.' | ||||||

| b. | Enkele junkies | komen | nooit | van hun verslaving | af. | |

| some junkies | come | never | from their addiction | prt. | ||

| 'Some of the junkies will never overcome their addiction.' | ||||||

The quantifier sommige can also evoke a “kind” interpretation of the noun it modifies. For example, sommige medicijnensome medicines in (240a) can refer to the kind of drugs that belong to the class of barbiturates. Enkele in (240b) again does not have this effect: it can only quantify over a contextually defined set of drugs.

| a. | Sommige medicijnen | kunnen | de rijvaardigheid | beïnvloeden. | |

| some medicines | may | the driving.ability | influence | ||

| 'Some drugs may affect driving ability.' | |||||

| b. | Enkele medicijnen | kunnen | de rijvaardigheid | beïnvloeden. | |

| some medicines | may | the driving.ability | influence | ||

| 'Some of these drugs may affect driving ability.' | |||||

Enkele can also be used as an attributive modifier. This use of enkele is characterized by the fact that enkele is followed by a singular noun. In (241a&b), the meaning of enkele is still quantificational in nature: despite the fact that the modified noun is singular, the noun phrase may actually refer to a non-singleton set of low cardinality. In (241c), on the other hand, the presence of the cardinal numeral éénone triggers a reading of enkele that can be properly rendered by English single. In (241d), enkele has the meaning “one-way”: the noun phrase een enkele reis is used to refer specifically to a one-way ticket.

| a. | Die enkele bezoekersg | die | hier | komt, | is het noemen | niet | waard. | |

| that enkele visitor | that | here | comes | is the mention | not | worth | ||

| 'Those few visitors who come here are not worth mentioning.' | ||||||||

| b. | Ik | ben | hier | slechts | een enkele keersg | geweest. | |

| I | am | here | only | a enkele time | been | ||

| 'I have been here only a couple of times.' | |||||||

| c. | Ik | ben | hier | slechts | één enkele keersg | geweest. | |

| I | am | here | only | a single time | been | ||

| 'I have only been here once.' | |||||||

| d. | een | enkele | reis | naar Amsterdam | |

| a | one.way | trip | to Amsterdam | ||

| 'a one-way ticket to Amsterdam' | |||||

When an existential quantifier is used as an argument, it is usually realized as the [+human] quantified personal pronoun iemandsomeone or the [-human] quantified personal pronoun iets/watsomething. The examples in (242) show that these quantifiers are typically used as weak quantifiers; as subjects they are typically used in expletive er constructions. The primed examples in (242), without the expletive er, are acceptable, but they generally require a special intonation pattern; these examples would be quite natural if the quantifier were assigned contrastive or emphatic focus. However, example (242b') with wat is still excluded. We refer the reader to Section 19.2 for further discussion of these pronouns.

| a. | Er | heeft | iemand | gebeld. | ||||

| there | has | someone | called | |||||

| 'Someone has called.' | ||||||||

| a'. | ? | Iemand | heeft | gebeld. | ||||

| someone | has | called | ||||||

| 'Someone has called.' | ||||||||

| b. | Er | is | iets/wat | gevallen. | ||||

| there | is | something | fallen | |||||

| 'Something has fallen.' | ||||||||

| b'. | ?? | Iets/*Wat | is | gevallen. | ||||

| something | is | fallen | ||||||

| 'Something has | ||||||||

| fallen.' | ||||||||

Many of the modifiers discussed in Subsection I can also be used as independent arguments. This is illustrated in the following subsections.

The examples in (243) show that, if the context provides sufficient information, it is possible to use sommige(n) as a pronominal quantifier instead of the full quantified noun phrases sommige studenten/boekensome students/books. If the quantifier ends in a schwa, Dutch orthography requires a (mute) suffix -n on the quantifier if the elided noun is [+human]; if the elided noun is [-human], this -n is not used.

| a. | Sommige studenten/Sommigen | gingen | naar | de vergaderzaal. | |

| some students/some | went | to | the meeting.hall |

| b. | Sommige boeken/sommige | zijn | uitverkocht. | |

| some books/some | are | sold.out |

The quantifier sommige(n) is strong when used as an independent argument. It is not immediately clear whether weak quantifiers such as enkelesome can also be used as independent arguments. Consider the examples in (244). The fact that we are dealing with expletive er constructions guarantees that the quantifiers in these examples are weak. The second occurrence of er in the primed examples is so-called quantitative er, which is associated with an interpretive gap in the noun phrase, which therefore has the form [QP enkele [NP e ]]. The doubly-primed examples show that quantitative er cannot easily be omitted; this suggests that the weak quantifier enkele behaves like the cardinal numerals in that it can only act as a modifier of a noun phrase (which happens to be phonetically empty in the singly-primed examples), not as an independent argument as in the doubly-primed examples.

| a. | ErExp | gingen | enkele studenten | naar de vergaderzaal. | weak quantifier | |

| there | went | some students | to the meeting.hall | |||

| 'There were some students going to the meeting hall.' | ||||||

| a'. | ErExp | gingen | erQuant | [enkele [e]] | naar de vergaderzaal. | |

| there | went | er | some | to the meeting.hall |

| a''. | ?? | ErExp | gingen | enkelen | naar de vergaderzaal. |

| there | went | some | to the meeting.hall |

| b. | ErExp | werden | enkele boeken | verkocht. | weak quantifier | |

| there | were | some books | sold | |||

| 'Some books were sold.' | ||||||

| b'. | ErExp | werden | erQuant | [enkele [e]] | verkocht. | |

| there | were | er | some | sold |

| b''. | *? | ErExp | werden | enkele | verkocht. |

| there | were | some | sold |

Note in passing that the non-main clause counterparts of the doubly-primed examples in (244) given in (245) are perfectly acceptable; the reason for this is that er can express more than one function in its location in the middle field of the clause. In the examples in (245), the single occurrence of er involves the conflation of the expletive and quantitative functions of er; cf. P37.5.3 for a detailed discussion. The acceptability of the examples in (245) is therefore not relevant to the present issue.

| a. | dat | erExp + Quant | enkelen | naar de vergaderzaal | gingen. | |

| that | there | sm | to the meeting.hall | went | ||

| 'that some of them went to the meeting hall.' | ||||||

| b. | *? | dat | erExp + Quant | enkele | verkocht | werden. |

| that | there | sm | sold | were | ||

| 'that some of them were sold.' | ||||||

When enkele is used as a strong quantifier, similar complications do not arise; the primed examples in (246) are perfectly acceptable, as are those in (243) with the strong quantifier sommige.

| a. | Enkele studenten | gingen | naar de vergaderzaal. | strong quantifier | |

| some students | went | to the meeting.hall |

| a'. | Enkelen | gingen | naar de vergaderzaal. | |

| some | went | to the meeting.hall |

| b. | Enkele boeken | waren | beschadigd. | strong quantifier | |

| some books | were | damaged |

| b'. | Enkele | waren | beschadigd. | |

| some | were | damaged |

Finally, in (247) we see that it is also possible to have quantitative er after the finite verb (in which case the spelling of enkelen in (246a') changes to enkele); this occurrence of er is like the one in (244) in that it simultaneously performs the function of expletive and quantitative er; the quantifier again functions as a weak quantifier modifying a phonetically empty noun phrase.

| a. | [Enkele [e]] | gingen | erExp + Quant | naar de vergaderzaal. | weak quantifier | |

| some | went | er | to the meeting.hall |

| b. | [Enkele [e]] | waren | erExp + Quant | beschadigd. | weak quantifier | |

| some | were | er | damaged |

We conclude that existential quantifiers can be used as independent arguments only when they are strong (i.e. have a partitive meaning); they cannot be used as independent arguments when they are weak.

The evidence given in (244) for the claim that weak quantifiers such as enkelesome cannot be used as independent arguments is not conclusive, since dropping quantitative er does not lead to fully unacceptable results. Stronger support for this claim is provided by the existential quantifier wat, which cannot be used as a strong quantifier. As shown in (248), dropping quantitative er in the doubly-primed examples leads to completely unacceptable results. Note that their embedded counterparts are again acceptable (e.g. dat er wat werden verkochtthat some of them were sold), due to the fact that er performs the expletive and quantitative functions simultaneously.

| a. | Er | gingen | wat studenten | naar de vergaderzaal. | |

| there | went | some student | to the meeting.hall | ||

| 'There were some students going to the meeting hall.' | |||||

| a'. | Er | gingen | er | [wat [e]] | naar de vergaderzaal. | |

| there | went | er | some | to the meeting.hall |

| a''. | * | Er | gingen | wat | naar de vergaderzaal. |

| there | went | some | to the meeting.hall |

| b. | Er | werden | wat boeken | verkocht. | |

| there | were | some books | sold | ||

| 'Some books were sold.' | |||||

| b'. | Er | werden | er | [wat [e]] | verkocht. | |

| there | were | er | some | sold |

| b''. | * | Er | werden | wat | verkocht. |

| there | were | some | sold |

Note also that the string without quantitative er in (248b'') becomes acceptable when the verb is singular, as in (249a). In this case we are not dealing with the use of the modifier wat as an independent argument, but with the colloquial form of the [-human] quantified personal pronoun ietssomething. In this use, wat can be modified by the degree modifiers heelvery and nogalquite, in which case it receives the interpretation “a lot”. Other modifiers that can be used are flinkquite and behoorlijk quite.

| a. | Er | werd | wat/iets | verkocht. | |

| there | was | something | sold | ||

| 'Something was sold.' | |||||

| b. | Er | werd | daar | heel/nogal | wat | verkocht. | |

| there | was | there | very/quite | something | sold | ||

| 'A lot was sold there.' | |||||||

For the remaining simple quantifiers discussed in Subsection I, we also generally find a contrast between weak and strong quantifiers. The weak quantifiers in (250), for example, occur only when quantitative er is present, which shows that they cannot be used as independent arguments.

| a. | Er | liggen | verscheidene/verschillende/ettelijke | boeken | op de tafel. | |

| there | lie | various/several/a.number.of | books | on the table | ||

| 'Various/several/a number of books are on the table.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | liggen | ??(er) | [verscheidene/verschillende/ettelijke [e]] | op de tafel. | |

| there | lie | er | various/several/a.number.of | on the table |

The forms allerlei and allerhande in (251), on the other hand, can be used as independent arguments in formal language. The independent use of these forms requires singular agreement on the finite verb: in example (251b) with quantitative er, the verb exhibits plural agreement; in example (251b') without quantitative er, the verb exhibits singular agreement. Independent allerlei and allerhande therefore pattern with wat in (249) rather than with sommige in (243).

| a. | Er liggen | allerlei/allerhande boeken | op de tafel. | |

| there lie | all.sorts.of books | on the table | ||

| 'All sorts of books are lying on the table.' | ||||

| b. | Er liggen/*ligt | er | [allerlei/allerhande [e]] | op de tafel. | modifier of [NP e ] | |

| there lie/lies | er | all.sorts.of (things) | on the table |

| b'. | Er ligt/*?liggen | allerlei/allerhande | op de tafel. | independent argument | |

| there lies/lie | all.sorts.of (things) | on the table |

Example (252) shows that the (formal) strong quantifier menig cannot be used as an independent argument, which may be related to the fact that the special form menigeen is used when the referent is [+human]; a corresponding [-human] form does not exist, though.

| a. | Menig staker | werd | ontslagen. | |

| many striker | was | fired | ||

| 'Many a striker was dismissed.' | ||||

| b. | Menigeen/*Menig | werd | ontslagen. | |

| many | was | fired |

The examples in (253) show that the phrase-like quantifiers deze of gene and een of ander can also be used independently. The latter is special, however, since it can be preceded by a definite determiner and must therefore be analyzed as part (perhaps the head) of an NP. The construction as a whole is also special, since the article het does not make the noun phrase definite, which is clear from the fact that it occurs as the subject of an expletive er construction in (253b).

| a. | Deze of gene | heeft | geklaagd. | |

| this or that | has | complained | ||

| 'Somebody (or other) has | ||||

| complained.' | ||||

| b. | Er | is gisteren | het een of ander | gebeurd. | |

| there | is yesterday | the one or other | happened | ||

| 'Something happened yesterday.' | |||||

In this context it should be noted that het een of ander seems to be in a paradigm with het een en ander, despite the fact that een en ander cannot be used as a prenominal quantifier; cf. (254). The form het een en ander is further special in that it triggers singular agreement on the verb, despite the fact that it is semantically plural in the sense that it refers to a non-singleton set of eventualities.

| a. | Er | is gisteren | het een en ander | gebeurd. | |

| there | is yesterday | the one or/and other | happened | ||

| 'Several things have happened yesterday.' | |||||

| b. | * | Er | is gisteren | een en ander ongeluk | gebeurd. |

| there | is yesterday | one and other accident | happened | ||

| 'Some accident has happened yesterday.' | |||||

Finally, example (255) shows that het nodige can also be used independently.

| Er | is gisteren | het nodige | gebeurd. | ||

| there | is yesterday | the needed | happened | ||

| 'A good many things happened yesterday.' | |||||