- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This section discusses a number of cases with more or less fixed combinations of noun/prepositional phrases and verbs, which often come close to forming complex verbal predicates, and in which the noun phrases seem to exhibit reduced referentiality features. In examples such as Ik wil een boek/de krant lezenI want to read a book/the newspaper, for instance, the direct objects do not exhibit the regular referential behavior of (in)definite noun phrases, since the speaker simply intends to refer to a specific kind of reading event. Subsection I begins with a discussion of cases with indefinite noun phrases, Subsection II will show that this kind of complex-predicate formation is especially common with definite phrases, which are called weak definites in the recent literature. Subsection III concludes with a brief discussion of some special cases.

This subsection discusses two cases of complex-predicate formation with indefinite noun phrases: cases with regular main verbs, as in een boek lezento read a book, and cases with so-called light verbs, i.e. verbs with a minimal semantic contribution, as in een kus gevento give a kiss.

Section 19.1.1.3 has shown that an indefinite noun phrase like een boeka book in (136a) can have at least two interpretations: it can be non-specific, in which case it refers to a book unknown to the speaker and the addressee, or it can be specific, in which case it refers to a book known to the speaker but not to the addressee. There is, however, a third, non-referential reading of this example, which expresses that the speaker wants to be engaged in a “book-reading event”. This reading comes very close to the meaning expressed in sentence (136b), where the direct object is not expressed, which suggests that in the intended reading, een boek lezento read a book comes very close to acting like a complex verbal predicate.

| a. | Ik | wil | vanavond | een boek | lezen. | |

| I | want | tonight | a book | read | ||

| 'I want to read a book tonight.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik wil vanavond lezen. |

The direct object must be sufficiently “general” to be interpreted as part of a complex verbal predicate. The number signs in (137) indicate that these examples do not easily allow the intended non-referential readings of the direct object, which must be construed either specifically or non-specifically.

| a. | # | Ik | wil | vanavond | een roman | lezen. |

| I | want | tonight | a book | read |

| b. | # | Ik | wil | vanavond | een gedicht | lezen. |

| I | want | tonight | a poem | read |

| c. | # | Ik | wil | vanavond | een krant | lezen. |

| I | want | tonight | a newspaper | read |

The verb is also lexically restricted: an example such as Ik wil vanavond een boek analyserenI want to analyze a book tonight would not easily be interpreted with a non-referential interpretation of een boek. Complex verbal predicates of the kind discussed here are typically found with the verb in the areas of recreation and entertainment: een wandeling maken to walk, een reis makento travel, naar een film kijkento watch a movie, etc. However, the number of cases is small compared to cases with a definite noun phrase; cf. Subsection II.

Complex verbal predicates with indefinite objects are common in so-called light verb constructions, as exemplified in (138). Light verb constructions feature verbs like makento make or gevento give which are semantically “bleached”; the main semantic contribution in these examples comes from the noun phrase which acts as the object of the verb, which is evident from the fact that the primeless examples are more or less equivalent to the primed examples.

| a. | Jan | maakt | een buiging | voor de koning. | |

| Jan | makes | a bow | for the king |

| a'. | Jan buigt | voor de koning. | |

| Jan bows | for the king |

| b. | Jan geeft | Peter | een kus. | |

| Jan gives | Peter | a kiss |

| b'. | Jan kust | Peter. | |

| Jan kisses | Peter |

| c. | Ik | geef | Jan | een schop | onder z’n kont. | |

| I | give | Jan | a kick | under his ass |

| c'. | Ik | schop | Jan onder z’n kont. | |

| I | kick | Jan under his ass |

The difference between the primeless and primed examples is mainly aspectual in nature: the former refer to singular, instantaneous events, whereas the latter can refer to multiple events or events that that occur over a period of time. For example, when Jan and Peter are making love, durative kussento kiss in (138b') would normally be a more appropriate description of the event than the instantaneous expression een kussen gevento give a kiss.

Plural indefinite noun phrases can also be used in these light verb constructions. The interpretation then is that the action denoted by the complex predicate is performed several times. This is clearest when the indefinite noun phrase is modified by a numeral; example (139a) can be paraphrased by (139b). Note that due to the durative meaning of the verb buigen, the repetitive meaning can also be present when the adverbial phrases are not used.

| a. | Jan maakt | (verscheidene/drie) | buigingen | voor de koning. | |

| Jan makes | several three | bows | for the king |

| b. | Jan buigt | (verschillende malen/drie keer) | voor de koning. | |

| Jan bows | several times/three times | for the king |

The presence of restrictive modifiers, as in the primed examples in (140), often favors a more referential interpretation of the noun phrase, although it should be noted that these adjectives are often used as manner adverbs modifying the event. This is illustrated by the primed examples.

| a. | Jan maakte | een elegante buiging | voor de koning. | |

| Jan made | an elegant bow | for the king |

| a'. | Jan boog | elegant | voor de koning. | |

| Jan bowed | elegantly | for the king |

| b. | Jan gaf | Peter | een adembenemende kus. | |

| Jan gave | Peter | a breathtaking kiss |

| b'. | ? | Jan kuste | Peter adembenemend. |

| Jan kissed | Peter breathtakingly |

| c. | Ik | gaf | Jan | een harde schop | onder zijn kont. | |

| I | gave | Jan | a hard kick | under his ass |

| c'. | Ik | schopte | Jan hard | onder z’n kont. | |

| I | kicked | Jan hard | under his ass |

Example (141) shows that definite noun phrases can also be construed as part of a complex verbal predicate. The sentence can be uttered out of the blue because the definite noun phrase de krantthe newspaper does not necessarily refer to a specific newspaper in the domain of discourse (domain D): if the reader has a subscription to three newspapers, he may intend to read all three issues of that day, and perhaps some issues of previous days as well. Definite noun phrases like de krant in (141) will be referred to as weak definites because they have at least partially lost their characteristic property of referring to unique entities in domain D.

| Ik | wil | een uurtje | de krant | lezen. | ||

| I | want | an hour | the newspaper | read | ||

| 'I want to read the newspaper for an hour.' | ||||||

There are also light verb constructions with definite objects. The examples in (142) show that the verb doento do is very productive in forming complex verbal predicates, especially in the field of denominating regular domestic activities. Some of these combinations are idiomatic in nature: speakers who consider the noun phrase de vaatthe dishes less common in regular argument positions can still use the complex verbal expression de vaat doen.

| a. | Ik | doe | de ramen | morgen. | also: de ramen lappen | |

| I | do | the windows | tomorrow | |||

| 'I will wash the windows tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | doe | de afwas/was. | also: (af)wassen | |

| I | do | the dishes/washing |

We will not discuss these examples in detail, as it seems that the definite noun phrases can be subsumed under the notion of weak definites: the definite noun phrases in (142) behave like de krant in (138) in that they can be used in out-of-the-blue contexts and do not have a unique referent in domain D. This is clear from examples such as Jan doet/lapt de ramen voor al zijn burenJan washes the windows for all his neighbors, where the reference of de ramen co-varies with the neighbor in question, and Jan haat de afwas doenJan hates doing the dishes, where de afwas receives a generic-like reading.

Carlson & Sussman (2005) refer to definite noun phrases such as de krant in (141) as seemingly indefinite definites. The notion of weak definites is to be preferred, however, because such definites differ from indefinite noun phrases in that they do not introduce new entities in domain D. In fact, they also fail to uniquely refer to presupposed entities in domain D, as regular definites do. This can be illustrated in several ways; cf. also Guevara (2014) and the references cited there.

Consider the examples in (143), in which the direct object introduces a new entity into domain D if it is indefinite (een krant), or refers to a unique entity that is contextually given if it is definite (de krant). In both cases, the pronoun hem can take the direct object as its antecedent (which is indicated by indices).

| a. | Ik | heb | een kranti | gekocht. | Wil | jij | hemi | lezen? | |

| I | have | a newspaper | bought. | Want | you | him | read | ||

| 'I have bought a newspaper. Do you want to read it?' | |||||||||

| b. | Ik heb de kranti | vanmorgen | gelezen. | Jij mag hemi nu hebben. | |

| I have the newspaper | this.morning | read. | You can him now have | ||

| 'I read the newspaper this morning. You can have it now.' | |||||

Things are different when the definite object is adjacent to the verb in clause-final position, as in (144a). Under a neutral intonation pattern (with non-emphatic sentence stress on the object), the complex-predicate reading becomes more prominent: the use of a deictic pronoun causes the sentence to be degraded, as the sentence no longer refers to reading an actual newspaper, but only to the activity of newspaper reading. A similar case is given in (144b) with a definite noun phrase embedded in a PP-complement of the verb: this case does not normally refer to the action of looking at a specific television set, but to watching some television program(s). The number signs indicate that the weak reading of the definite noun phrase makes the referential identity indicated by the indices less felicitous.

| a. | # | Ik heb vanmorgen | de kranti | gelezen. | Jij | mag | hemi | nu | hebben. |

| I have this.morning | the newspaper | read. | You | can | him | now | have | ||

| 'I have been reading the newspaper this morning.' | |||||||||

| b. | # | Ik | heb | zojuist | naar de televisiei | gekeken. | Hiji is kapot. |

| I | have | just | at the television | looked. | he is broken | ||

| 'I have just watch television.' | |||||||

There may be some disagreement among speakers as to whether or not the regular referential reading of the definite noun phrase de krant in (144a) is possible, but all speakers will agree that this reading is blocked in out-of-the-blue contexts: example (145a) can be uttered unexpectedly, even to a complete stranger, and therefore cannot involve a contextually determined newspaper. Note that the fact that example (145b) would be unintelligible in such a context shows that weak definites are sensitive to lexical restrictions; cf. Subsection B.

| a. | Heeft u | vanmorgen | de krant | gelezen? | weak definite | |

| have you | this.morning | the newspaper | read | |||

| 'Did you read the newspaper this morning?' | ||||||

| b. | Heeft u | vanmorgen | de roman | gelezen? | regular definite | |

| have you | this.morning | the novel | read | |||

| 'Did you read the novel this morning?' | ||||||

That weak definites do not have the regular reading of definite noun phrases is also clear from elliptical contexts such as (146). The two examples differ in that (146b) expresses that Jan and Marie have read the same, contextually determined, novel (the so-called strict reading) while (146a) does not presuppose that they read the same newspaper (the so-called sloppy reading). This follows on the assumption that weak definites differ from regular definites in that they do not refer to a unique referent in domain D.

| a. | [Jan heeft | zojuist | de krant | gelezen] | en | [Marie ook]. | weak definite | |

| Jan has | just | the newspaper | read | and | Marie too | |||

| 'Jan has just read the newspaper and so has Marie.' | ||||||||

| b. | [Jan heeft | de roman | gisteren | gelezen] | en [Marie ook]. | regular definite | |

| Jan has | the novel | yesterday | read | and Marie too | |||

| 'Jan read the newspaper this morning and Marie did too.' | |||||||

Weak definites also differ from regular definites in that they are not compatible with a de re reading: example (147a) expresses that the speaker’s friends all read some, but not necessarily the same, newspaper (the de dicto reading), whereas example (147b) states that they all read the same, contextually determined novel (the de re reading). This again follows if we assume that weak definites differ from regular definites in that they do not refer to a unique referent in domain D.

| a. | Al mijn vrienden | lezen | de krant. | weak definite | |

| all my friends | read | the newspaper |

| b. | Al mijn vrienden | lezen de roman. | regular definite | |

| all my friends | read the novel |

Weak definites differ from regular definites in that they usually do not allow pluralization and modification; exceptions will be discussed in subsection B. This is clear from the fact that the examples in (148) do not allow the complex-predicate reading: these examples involve some contextually defined newspaper(s) and therefore cannot be used in out-of-the-blue contexts.

| a. | Jan heeft | de kranten | gelezen. | regular definite | |

| Jan has | the newspapers | read |

| b. | Jan heeft de rechtse krant gelezen. | regular definite | |

| Jan has the right-wing newspaper read |

We have seen that some of the special properties of weak definites are related to the fact that they differ from regular definites in that they do not refer to specific entities in domain D: this explains why they cannot be the antecedent of a deictic pronoun, can be used in out-of-the-blue contexts, trigger sloppy-identity readings in elliptical contexts, and have a de dicto reading. We have also seen that they usually cannot be pluralized or modified. The inability of weak definites to be modified may be related to the fact that modification usually makes the definite noun phrase insufficiently “general” to be construed as part of a complex verbal predicate. This idea fits well with Guevara’s (2014) central claim that weak definites differ from regular definites in that they do not refer to entities, but to kinds. In this context, it is worth noting that definite generic noun phrases like de zebra in (149) share certain properties with weak definites; cf. Section 19.1.1.5. First of all, they do not refer to a specific entity in domain D, but to what we have called a prototypical member of the set denoted by the noun, and in addition they usually cannot be pluralized or modified; this is illustrated in (149b&c).

| a. | De zebra | is gestreept. | generic definite | |

| the zebra | is striped |

| b. | De zebra’s zijn gestreept. | regular definite | |

| the zebras are striped |

| c. | De oude zebra | is gestreept. | regular definite | |

| the old zebra | is striped |

For further discussion of the similarity between weak definites and definite generic noun phrases, we refer the reader to Guevara (2014:§3). We will return to this issue briefly in Subsection C.

Subsection I has shown that complex-predicate formation with indefinite noun phrases is mainly restricted to the domain of recreation and entertainment. Similar restrictions on the lexical domain apply to weak definites: non-referential definite noun phrases are typically used as part of complex predicates denoting stereotypical activities. Their distribution is also subject to many idiosyncratic restrictions.

Weak definites are very common in the domain of art, entertainment, and recreation. The definite noun phrases in the sentences in (150) do not refer to a specific building or location, as can be seen from the fact that these sentences can be uttered out of the blue, but they do express that the speaker wants to be involved in some kind of activity, like visiting a museum or watching a movie outdoors.

| a. | Ik wil vandaag naar het museum. | |

| I want today to the museum |

| b. | Ik | ga | vanavond | naar de film/bioscoop. | |

| I | go | tonight | to the movie/cinema |

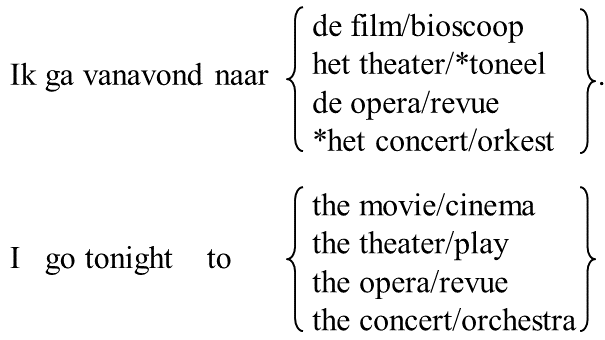

In these cases, we are often dealing with more or less fixed combinations. This becomes clear in the constructions in (151), where we compare the acceptability judgments on noun phrases in their weak (non-referential) readings from more or less the same semantic domain (“performance art” in the broad sense). In (151) we see that noun phrases like het toneelthe play/theater and het concertthe concert cannot be used in constructions such as (150b). Note that speakers’ judgments seem to vary somewhat; the judgments in the examples below are our own.

|

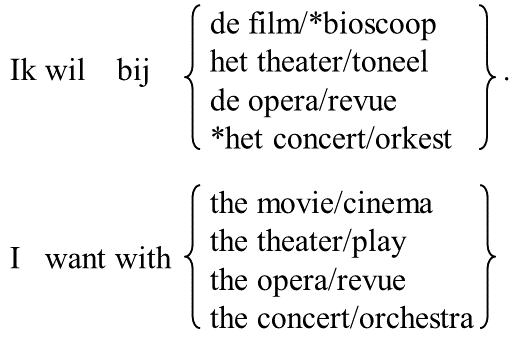

Something similar can be observed in the examples in (152), which are quite common ways for the speaker to express that he wants to make his career in the world of film, theater, etc. It is not the case, however, that this applies to all artistic careers. For example, while it is possible for the speaker to use Ik wil bij de opera to express that he wants to pursue a career as an opera singer, he cannot express that he wants to become a member of an orchestra by saying Ik wil bij het orkest. This sentence can only be used in a referential reading of the noun phrase het orkest: “I want to join the orchestra”.

|

For the speaker to express that one would like to make a career as a musician (e.g. as a member of an orchestra), he could use the construction in (153a). This construction is a very restricted, idiomatic construction that does not allow any of the other definite noun phrases; (153b) is only acceptable in the literal sense, where het theater and, more marginally, de opera refer to buildings where performances take place (an option missing for de film).

| a. | Ik | wil | de muziek | in. | |

| I | want | the music | into | ||

| 'I want to make a career in music.' | |||||

| b. | Ik | wil | *de film/#het theater/#de opera | in. | |

| I | want | the movie/the theater/the opera | into |

Note that example (153a) involves a postpositional (i.e. directional) PP. To express that someone is a professional musician, we would use a prepositional (i.e. locational) PP instead, as in (154a). The (b)-examples show that this construction does not allow any of the other definite noun phrases either: only the literal meanings are available.

| a. | Hij | zit | in de muziek. | |

| he | sits | in the music | ||

| 'He is a professional musician.' | ||||

| b. | Hij | zit | in *de film/#het theater/#de opera. | |

| he | sits | in the movie/the theater/the opera |

Weak definites are very common in sentences referring to outdoor activities, and they often specify the natural space in which the activity takes place. Importantly, however, they do not usually refer to specific locations, which is clear from the fact that all the sentences in (155) can be uttered out of the blue and followed by further specification of the location: Laten we naar ... gaanLets go to ...’, where the dots can be filled in by De Veluwe (nature reserve), Zandvoort (town on the coast) or FrankrijkFrance.

| a. | Ik | wil | wandelen | in het bos. | |

| I | want | to walk | in the wood |

| b. | Ik | wil | luieren | op het strand. | |

| I | want | idle | on the beach | ||

| 'I want to idle on the beach.' | |||||

| c. | Ik | wil | naar het buitenland | in de vakantie. | |

| I | want | abroad | in the vacation | ||

| 'I want to go abroad on holiday.' | |||||

Again, there are idiosyncratic restrictions on the nouns that can head weak definites: the examples in (156) are not easily used spontaneously: the definite noun phrase het meer would normally be interpreted as referring to a specific location and the definite noun phrase de zee gives rise to a marked result, possibly because the bare noun zee is normally used in this case.

| a. | # | Ik | wil | zeilen | op het meer. |

| I | want | to sail | on the lake |

| b. | Ik | wil | zeilen | op (#de) zee. | |

| I | want | to sail | on the sea |

The examples in (157) show that weak definites can occasionally appear in plural form, which seems to contradict the claim in Subsection A6 that weak definites cannot be pluralized. However, when referring to a particular geographical area, duinen and bergen seem to be pluralia tantum, which is clear from the fact that their singular counterpart is marked or impossible in this context; hence they seem to be only apparent counterexamples to the claim.

| a. | Ik | wil | wandelen | in de duinen/??het duin. | |

| I | want | walk | in the dunes/the dune | ||

| 'I want to walk in the dunes.' | |||||

| b. | Ik | wil | klimmen | in de bergen/*berg. | |

| I | want | climbing | in the mountains/mountain | ||

| 'I want to climb mountains.' | |||||

Nouns denoting highly trained medical personnel like dokterdoctor, tandartsdentist, fysiotherapeutphysiotherapist and psychiaterpsychiatrist (but not verplegernurse) can be used as weak definites in cases like (158a). We are dealing with weak definites here, as is clear from the fact that such examples can be uttered out of the blue, e.g. as a reason for being late the next day, without the speaker knowing who will actually provide the medical care. That the definite noun phrase does not refer to some unique entity in domain D is especially clear in examples such as (158b), which can be used even when the speaker does not expect to speak to the doctor himself, but to a receptionist or a doctor’s assistant.

| a. | I moet morgen | naar de dokter. | |

| I must tomorrow | to the doctor | ||

| 'I have to go to the doctor tomorrow.' | |||

| b. | Ik | bel | de dokter | even. | |

| I | phone | the doctor | prt | ||

| 'I will phone the doctor.' | |||||

These examples show that the intended message can be quite different from the compositional meaning of the sentence: the examples in (158) express something like “I need some medical attention” or “I am going to see about some medical service”. Similar meaning extensions can be found when the noun denotes a medical institution, such as ziekenhuishospital in (159), which can be used to express that Jan needs to get/is getting specialist medical treatment, even if the speaker does not know which hospital will provide it.

| a. | Jan moet naar het (psychiatrisch) ziekenhuis. | |

| Jan must to the psychiatric hospital | ||

| 'Jan has to go to the hospital.' |

| b. | Jan ligt in het (psychiatrisch) ziekenhuis | |

| Jan lies in the psychiatric hospital | ||

| 'Jan is in the hospital'. |

Note in passing that the examples seem to contradict the claim in Subsection A6 that weak definites cannot be modified. The modified noun seems to denote a special subtype of hospital, which is apparently sufficiently “general” to license the complex-predicate meaning of “needing/receiving psychiatric help”.

The examples in (159) are interesting in that there is cross-linguistic variation on the question of whether the definite article must be expressed, as illustrated by the contrast between American and British English in (160), taken from Guevara (2014).

| a. | Laura went to the hospital. | American English |

| b. | Laura went to hospital. | British English |

Weak definites and bare nouns usually seem to be able to perform the same function in PPs, the choice between them being completely idiosyncratic, as will be clear from the contrast between the two examples in (161); cf. P34.1, sub II, for more examples. This finding is important, because it underscores the claim that definite articles in weak definites do not have the same meaning as those in regular noun phrases; it actually suggests that they do have no indispensable semantic contribution to make.

| a. | Jan gaat | nog | naar (*de) school. | |

| Jan goes | still | to the school | ||

| 'Jan is still enrolled in grammar school.' | ||||

| b. | Jan gaat | al | naar *(de) universiteit. | |

| Jan goes | already | to the university | ||

| 'Jan is already enrolled in university.' | ||||

Cases similar to those in (158) and (159) can also be found outside the medical domain, and are in fact quite common in relation to shopkeepers and shops, as shown in the examples in (162); note that in Dutch it is not always clear whether nouns like bakkerbaker, slagerbutcher and melkboermilkman refer to people with a specialized profession or to their shops.

| a. | Ik | ga | naar de baker. | |

| I | go | to the baker(y) | ||

| 'I am going to get some bread.' | ||||

| b. | Ik | ga | naar de supermarkt. | |

| I | go | to the supermarket | ||

| 'I am going shopping'. | ||||

Definite noun phrases are not necessarily interpreted specifically (or generically) in examples such as (163a): such examples are ambiguous and can mean either that the speaker takes a particular bus (e.g. the one that comes around the corner), or that he takes the bus qua means of transport (i.e. any bus). In many cases, such as (163b&c), the latter reading is clearly the preferred one.

| a. | Ik | neem | de bus. | |

| I | take | the bus | ||

| 'I will take a specific bus.' or 'I will go by bus.' | ||||

| b. | Ik | doe | alles | met de bus. | |

| I | do | everything | with the bus | ||

| 'I only travel by bus.' | |||||

| c. | Ik | heb | een hekel | aan de bus. | |

| I | have | a dislike | for the bus | ||

| 'I hate travelling by bus.' | |||||

On the second reading in (163a), de bus ‘the bus’ is not a uniquely referring noun phrase, but is interpreted as a subpart of the complex verbal predicate de bus nementake the bus, i.e. to engage in bus travel. Similar interpretations are possible for noun phrases with definite determiners with a variety of “means of transportation” as their head. To give an idea of the range of possibilities, some acceptable examples are given in (164a-c).

| a. | Ik | neem | de bus/trein/tram/metro. | |

| I | take | the bus/train/“tram”/subway |

| c. | Ik | neem | de auto/fiets/lift. | |

| I | take | the car/bike/elevator |

| b. | Ik | neem | het vliegtuig/de boot. | |

| I | take | the airplane/the boat |

| d. | Ik | neem | een/*?de taxi. | |

| I | take | a/the taxi |

Note that the noun taxi in (164d) is special in that it requires an indefinite article. The fact that we apparently cannot predict which article will be used may simply reflect the more or less idiomatic character of this construction with the verb nemen (and its more colloquial near-equivalent pakkentake, fetch, catch). That we are dealing with idiom-like constructions may also be supported by the fact that there are clear idiomatic cases with this verb, which are given in (165b). Although (165a) seems to be a direct instantiation of the general pattern in (164), this example is also special in that the noun benenwagen can only be used in “means of transportation” contexts.

| a. | Ik | neem | de benenwagen. | |

| I | take | the leg-car | ||

| 'I go on foot.' | ||||

| b. | Ik | neem | de benen. | |

| I | take | the legs | ||

| 'I am running away.' | ||||

The examples in (166) show that the “means of transportation” interpretation of noun phrases with a definite article is also found in PPs in clauses with motion and position verbs: example (166a) involves an instrumental met-PP, while the PPs in (166b) are locational complementives.

| a. | Ik | ga | wel | met de bus/trein/fiets/auto/taxi/benenwagen. | |

| I | go | prt | with the bus/train/bike/car/taxi/leg-car |

| b. | Ik | stap | wel | op de bus/trein/boot. | |

| I | step | prt | on the bus/train/boat |

| c. | Ik | spring | voor de trein. | |

| I | jump | before the train |

| d. | Ik | zit | vaak | in de trein. | |

| I | sit | often | in the train |

The instrumental met-PP in (166a) sometimes alternates with a per-PP, with the Latinate preposition per, which systematically takes bare (i.e. determinerless) complement noun phrases. The fact that some of the cases in (166a) alternate with determiner-less cases in (167) supports the earlier suggestion that the definite article de in (166a) has no indispensable semantic contribution to make.

| Ik | ga | wel | per ∅ bus/trein/??fiets/?auto/taxi/*benenwagen. | ||

| I | go | prt | by ∅ bus/train/bike/car/taxi/leg-car | ||

| 'I will go by bus/train/...' | |||||

Like noun phrases denoting a means of transportation, noun phrases denoting a means of communication may contain a definite article that does not necessarily contribute to the notion of definiteness. This is particularly clear in (168b), where the article de can be omitted without any noticeable change in meaning.

| a. | Pak | de telefoon | en | vertel | het | hem! | |

| take | the telephone | and | tell | it | him | ||

| 'Phone him up and tell him!' | |||||||

| b. | Ik | zag | het | op (de) televisie. | |

| I | saw | it | on the television | ||

| 'I saw it on television.' | |||||

| c. | Ik | hoorde | het gisteren | op *(de) radio. | |

| I | heard | it | yesterday on the radio | ||

| 'I heard it on the radio yesterday.' | |||||

Weak definites typically occur as direct objects, prepositional objects, or complementives. The fact that these parts of speech are all complements of the main verb may explain why they tend to trigger complex-predicate readings.

| a. | Jan heeft | de krant | gelezen. | direct object | |

| Jan has | the newspaper | read | |||

| 'Jan has read the newspaper' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | naar de televisie | gekeken. | PP-object | |

| Jan has | at the television | looked | |||

| 'Jan has watched television.' | |||||

| c. | Jan is naar de dokter/het ziekenhuis | geweest. | complementive | |

| Jan is to the doctor/the hospital | been | |||

| 'Jan has had a medical examination.' | ||||

However, this does not exhaust the possibilities, as we have seen that weak definites can also occur in adverbial phrases; we repeat some examples in (170). In such cases a complex-predicate analysis is less plausible.

| a. | Ik | ga | wel | met de bus/trein/... | |

| I | go | prt | with the bus/train/... | ||

| 'I will go by bus/train/...' | |||||

| b. | Ik | hoorde | het | gisteren | op de radio. | |

| I | heard | it | yesterday | on the radio | ||

| 'I heard it on the radio yesterday.' | ||||||

According to Guevara (2014), weak definites do not often occur as subjects, but she gives some English examples involving means of transport and professions. Similar Dutch examples are given in (171): that we are dealing with weak definites is suggested by the fact that these examples can be used out of the blue, and that there may be more buses and postmen involved in providing the services mentioned.

| a. | De bus | rijdt | niet | vandaag. | |

| the bus | drives | not | today | ||

| 'There is no bus service today.' | |||||

| b. | De postbode | bezorgt | het boek | vandaag. | |

| the postman | delivers | the book | today | ||

| 'The postman delivers the book today.' | |||||

The examples in (171) show a strong resemblance to the generic ones in (172), but it does not seem possible to give a fully unified analysis of the two sets, given that the adverb vandaagtoday forces an episodic reading on the examples in (171). The similarity is not surprising, however, since we have seen that weak definites and generic definite noun phrases share several properties; cf. Subsection IIA6.

| a. | De bus | rijdt | niet | op zondag. | |

| the bus | drives | not | on Sunday | ||

| 'There is no bus service on Sundays.' | |||||

| b. | De postbode | bezorgt | de post | dagelijks. | |

| the postman | delivers | the post | daily | ||

| 'The postman delivers the post daily.' | |||||

Although this does not hold across-the-board, we can conclude that weak definites are especially common in the positions that can enter into complex-verb formation, i.e. the complement position of the main verb. Subsection IIA1 already noted that scrambling of direct objects, as in (173b), disfavors the weak-definite reading, which is not surprising given that this kind of scrambling is only possible when the noun phrase refers to some entity in domain D; cf. Section 22.1.3 for further discussion. We can add that the same holds for topicalization, as in (173c). The reason for this is that this movement operation usually introduces a new discourse topic/focus; cf. chapter V11. These information-structural conditions on movement are incompatible with the fact that weak definites do not refer to any entity in the discourse domain.

| a. | Ik heb vanmorgen | de krant | gelezen. | weak-definite reading allowed | |

| I have this.morning | the newspaper | read | |||

| 'I have been reading the newspaper this morning.' | |||||

| b. | Ik heb de kranti | vanmorgen ti | gelezen. | regular reading favored | |

| I have the newspaper | this.morning | read | |||

| 'I read the newspaper this morning.' | |||||

| c. | # | De kranti | heb | ik | vanmorgen ti | gelezen. | regular reading only |

| the newspaper | have | I | this.morning | read | |||

| 'I read the newspaper this morning.' | |||||||

For completeness’ sake, the examples in (174) show that topicalization also disfavors the weak-definite reading of noun phrases embedded in a PP.

| a. | Ik | heb | naar de televisie | gekeken. | weak-definite reading preferred | |

| I | have | to the television | looked | |||

| 'I have watched television.' | ||||||

| b. | Naar de televisiei | heb | ik | zojuist ti | gekeken. | regular reading only | |

| to the television | have | I | just | looked | |||

| 'I have just looked at the television.' | |||||||

We conclude this section with a discussion of articles in three more special environments: idioms, noun phrases referring to mental/physical conditions, and so-called impersonal/locational krioelenswarm constructions.

It is not surprising that articles can also exhibit deviant semantics in idiomatic expressions. In (175) we give some examples with an indefinite article, and in (176) some examples with a definite article. There is no sense in which the articles in these examples evoke a referential reading; the (in)definite noun phrases are simply part of idiomatic clusters of verb plus (prepositional) object. Some of the nouns also occur as referential nouns in (present-day) Dutch with the meaning given in the glosses; the nouns repeated in small caps in the glosses do not.

| a. | het | op | een lopen | zetten | ||||

| it | on | a runinfinitive | put | |||||

| 'to start running away' | ||||||||

| c. | iemand | een poets | bakken | |||||

| somebody | a poets | bake | ||||||

| 'to play a trick on somebody' | ||||||||

| b. | iemand | een loer | draaien | |||

| somebody | a loer | turn | ||||

| 'to deceive somebody' | ||||||

| d. | ∅ spoken | zien | ||||

| ∅ ghosts | see | |||||

| 'to be mistaken' | ||||||

| a. | op de tocht | staan | |

| on the draught | stand | ||

| 'to be in a draughty spot' | |||

| b. | in de clinch | liggen | met iemand | |

| in the clinch | lie | with somebody | ||

| 'to quarrel with somebody' | ||||

| c. | iets | onder de loep | nemen | |

| something | under the magnifying glass | take | ||

| 'to investigate something' | ||||

| d. | iets | op de korrel | nemen | |

| something | on the pellet | take | ||

| 'to criticize something' | ||||

| e. | ergens | de balen | van | hebben | |

| something | the balen | of | have | ||

| 'to be fed up with something' | |||||

| f. | iets/iemand | aan de praat | krijgen | |

| someone/thing | on the talk | get | ||

| 'to get someone to talk/something to work' | ||||

Articles in noun phrases headed by nouns denoting a disease often exhibit a special behavior. If we restrict ourselves to the syntactic frame [VP heeft/krijgt __] in (177), we can observe that disease-denoting nouns come in three groups: the first group in (177a) requires the presence of a definite article; the second group in (177b) optionally combines with a definite article; the third group in (177c) cannot combine with an article. The fact that none of the noun phrases in (177) are interpreted as uniquely referring expressions suggests that the article de is semantically vacuous in constructions of this type.

| a. | Jan heeft/krijgt | *(de) pest/bof/tering | |

| Jan has/gets | the pestilence/mumps/consumption |

| b. | Jan heeft/krijgt | (de) | griep/mazelen/pokken. | |

| Jan has/gets | the | flu/measles/smallpox |

| c. | Jan heeft/krijgt | (*de) | kanker/aids/tuberculose. | |

| Jan has/gets | the | cancer/AIDS/tuberculosis |

Some names of diseases can also be used in figurative speech, as part of the idiomatic register. This is illustrated in (178) for the noun pestpestilence/plague: both examples refer to a mental state of the speaker. Note that, as in (177a), the definite article is obligatory in these examples, even though it seems to make no semantic contribution.

| a. | Ik | heb/krijg | (er) | de pest | in. | |

| I | have/get | there | the plague | in | ||

| 'I am very annoyed.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | heb/krijg | de pest | aan die vent! | |

| I | have | the plague | on that guy | ||

| 'I cannot stand that guy!' | |||||

Names of diseases are also common in curses. An interesting feature of this usage is that the disease denoting noun is always preceded by the definite article, regardless of the category of noun it belongs to. In (179), we showed this for each of the three types in (177).

| Krijg | *(de) | pest/pokken/kanker! | ||

| get | the | pestilence/smallpox/cancer | ||

| 'Go to hell!' | ||||

Consider the examples in (180), which show that the verb krioelento swarm can appear in three different verb frames. The given translations show that example (180a) is different from the examples in (180a&b). Example (180a) is a run-of-the-mill intransitive construction in which the noun phrase de mieren behaves like a regular definite noun phrase: it refers to a contextually determined set of ants (viz. the ants known to live in the garden). The examples in (180a&b), on the other hand, are more specialized constructions in which the definite NP behaves more like an indefinite noun phrase: it introduces a set of ants in domain D, and the reader is informed that they are in the garden. Note that the use of definite noun phrases in this construction is a relatively recent innovation; cf. Hoeksema (2009) for details.

| a. | De mieren | krioelen | in de tuin. | regular intransitive | |

| the ants | swarm | in the garden | |||

| 'The ants are swarming in the garden.' | |||||

| b. | Het | krioelt | van de mieren | in de tuin. | impersonal construction | |

| it | swarms | of the ants | in the garden | |||

| 'The garden is swarming with ants.' | ||||||

| c. | De tuin | krioelt | van the mieren. | location construction | |

| the garden | swarms | of the ants | |||

| 'The garden is swarming with ants.' | |||||

Example (180a) is a regular construction with the lexical verb krioelento swarm, while the examples in (180a&b) are more special. The latter are characterized by the use of a van-PP with a high-degree reading in the sense that de Npl refers to an unspecified but very large set of Ns, with a concomitant bleaching of the meaning of the verb has bleach. That the verb is bleached can be seen from the paraphrasing translations of the examples in (181).

| a. | De studenten | stikken | in the collegezaal. | regular intransitive | |

| the students | choke | in the lecture.hall | |||

| 'The students are suffocating in the lecture hall.' | |||||

| b. | Het | stikt | van de studenten | in the collegezaal. | impersonal construction | |

| it | chokes | of the students | in the lecture.hall | |||

| 'There are an awful lot of students in the lecture hall.' | ||||||

| c. | De collegezaal | stikt | van de studenten. | location construction | |

| the lecture.hall | chokes | of the students | |||

| 'There are an awful lot of students in the lecture hall.' | |||||

Note that the degree of bleaching of the verb can vary from case to case. For example, in the (a)-examples in (182), the motion verb krioelen still seems to impose an agency restriction on the nominal part of the van-PP, while the (b)-examples show that the animateness restriction imposed by stikken has been completely lost.

| a. | * | Het | krioelt | van de bloemen | in de tuin. | impersonal construction |

| it | swarms | of the flowers | in the garden |

| a'. | * | De tuin | krioelt | van the bloemen. | location construction |

| the garden | swarms | of the ants |

| b. | Het | stikt | van de fouten | in die tekst. | impersonal construction | |

| it | chokes | of the error | in that tekst | |||

| 'There are an awful lot of errors in that text.' | ||||||

| c. | Die tekst | stikt | van de fouten. | location construction | |

| that tekst | chokes | of the error | |||

| 'There are an awful lot of errors in that text.' | |||||

The examples in (180) and (181) show that the core meaning of definite NPs can be suppressed in specialized constructions; similar observations can be made for constructions of the type in (183); cf. Hoeksema (2009) for further details.

| a. | Jan barst | van het geld. | |

| Jan burst | of the money | ||

| 'Jan is bursting with money.' | |||

| b. | Marie stikt | van de zenuwen. | |

| Marie chokes | of the nerves | ||

| 'Marie is choking with nerves.' | |||

Since the impersonal and locational constructions alternate productively, they will be discussed in more detail in Section V3.3.3, sub II.