- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

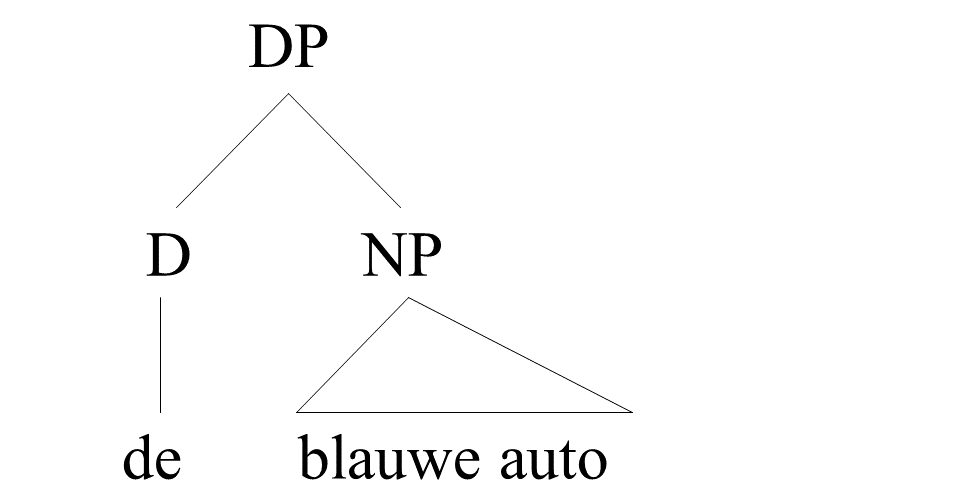

This chapter discusses the semantic and syntactic behavior of determiners. In the current generative framework, it is generally taken for granted that a determiner defines its own endocentric projection in the structure of the noun phrase; cf. Abney (1987). It is taken to be the head of a so-called determiner phrase (DP), which is located on top of the lexical projection of the head noun, NP. Schematically, example (1a) can be represented in labeled bracketing, as in (1b), or as a tree diagram, as in (1c). Note that we use the term “noun phrase” in a neutral way, while the terms DP and NP are used to refer to the substructures labeled as such in (1b&c).

| a. | de | blauwe | auto | |

| the | blue | car |

| b. | [DP [D de] [NP blauwe auto]] |

| c. |  |

The DP structure of noun phrases formally recognizes the fact that it is the determiner which is the syntactic head, and as such determines the referential/quantificational properties and the syntactic distribution of the noun phrase as a whole (apart, of course, from the semantic selection restrictions imposed by e.g. the verb on the denotation of the head noun of its complement).

There are two main types of determiners: articles and pronouns, which will be discussed in 19.1 and 19.2, respectively. Of course, noun phrases can also be introduced by a cardinal numeral or a quantifier such as sommigesome; these will not be discussed in this chapter, but in Chapter 20. Under the generally accepted assumption that a phrase has exactly one head, the claim that demonstrative/interrogative and possessive pronouns are determiners and thus occupy the D position of the DP can be motivated by the fact that they are in complementary distribution with the articles as well as with each other; cf. Corver et al. (2013:130). For example, it is impossible to have both an article and a demonstrative or interrogative pronoun in a single DP. This is illustrated in (2) for combinations of two types of non-interrogative determiners; of course, examples containing all three types of determiners are also excluded.

| a. | * | het | dit/welk boek | article and demonstrative/interrogative pronoun |

| the | this/which |

| a'. | * | dit/welk het boek |

| b. | * | het | mijn boek | article and possessive pronoun |

| the | my book |

| b'. | * | mijn het boek |

| c. | * | dat/welk | mijn boek | possessive and demonstrative pronoun |

| that/which | my book |

| c'. | * | mijn dat boek |

Note, however, that the claim that articles and pronouns are both determiners is weakened by the fact that this does not seem to be universally true: some languages, like Italian or Greek, do not exhibit the complementary distribution of Dutch articles and possessive/demonstrative pronouns (cf. Alexiadou et al. 2007:93).

Personal pronouns are also included in this chapter because there are several reasons to consider them as determiners as well. Semantically, they are similar to determiners in that they have primarily a referential function: their descriptive content is limited and certainly does not exceed that of possessive pronouns. Moreover, if it is assumed that personal pronouns are within the NP-domain, it is not easy to explain why they cannot be preceded by an article or a demonstrative/possessive pronoun, whereas this follows immediately when they occupy the D-position; cf. Longobardi (1994) and Alexiadou et al. (2007:211-9) for further empirical support from Italian and Serbo-Croatian for the claim that personal pronouns are determiners. The examples in (3) are with non-neuter determiners, but the same judgments arise with their neuter counterparts, except for het ikthe self/ego, in which case ik simply functions as a noun, as indicated by the fact that it has a plural form; cf. onze ikkenour egos.

| a. | * | de | ik/jij/hij |

| the | I/you/he |

| a'. | * | deze | ik/jij/hij |

| this | I/you/he |

| b. | * | de | wij/jullie/zij |

| the | we/you/they |

| b'. | * | deze | wij/jullie/zij |

| these | we/you/they |

Before discussing the articles in 19.1, we want to make some general remarks about the structure of the noun phrase in (1). The NP in this structure can be said to determine the denotation of the noun phrase: it acts like a predicate, and can therefore be represented as a set of entities that have in common that they satisfy the description provided by the NP; the NP blauwe autoblue car denotes the set of entities that have the properties of being a car and being blue; cf. Section A24.3. Determiners, on the other hand, are usually used to determine the reference of the noun phrase. For example, a definite determiner like de in de blauwe autothe blue car expresses that the denotation set of the NP blauwe autoblue car contains exactly one entity and that it is this entity that the speaker is referring to. The fact that a definite determiner has this meaning leads us to the relation between language and reality.

The relationship between language and reality (i.e. the actual world) has given rise to ardent debates, and we will certainly not attempt to resolve all of the issues raised. However, we would like to point out that many of the problems discussed in these debates have their origin in the assumption that language is directly related to reality. Consider example (4). Given the generally accepted idea that a singular noun phrase with a definite determiner like de refers to a unique entity, this example is problematic because the noun phrase de Nederlandse presidentthe Dutch president does not refer to an entity in the real world, which means that at first glance this example cannot be assigned a truth value.

| De Nederlandse president | is | een begaafde man. | ||

| the Dutch president | is | a gifted man |

Another problem is that it seems to be beyond the power of the language user to determine what reality actually is; if we want to make objective statements about reality, we have to go beyond our personal experience and enter the domain of science. The language user does not refer directly to reality, but to his internalized conception of reality, which is invoked in his speech acts. For example, a sentence like (4) can be seriously uttered by anyone who has the erroneous belief that the Dutch prime minister is the president of the Netherlands, and consequently the speaker will assign a truth value to this sentence. In other words, by assuming that a noun phrase does not refer to entities in the material world but to entities in the speaker’s internalized conceptualization of the material world, the reference problem in (4) dissolves.

The next question is what a language user is actually doing when he or she utters an example such as (4). The definite article de expresses that in the speaker’s conception of the universe, there is a unique entity that has the property of being the Dutch president, and it is this entity that the property of being a gifted man is predicated of. Of course, this conception of reality may clash with the conception of reality held by the listener, who is then likely to correct the speaker by saying that the person in question is not the president but the prime minister. What this shows is that language users do not appeal to knowledge of reality (which they may be assumed to lack), but to knowledge of their internalized conceptualization of reality. Although the conceptualizations of reality may differ from person to person, there is generally enough overlap to make communication more or less successful: indeed, one could argue that the goal of communication is to eliminate discrepancies between the conceptualizations of reality held by the participants in the discourse, by correcting or updating the encoded knowledge; cf. Verhagen (2005).

Often participants do not even use their full conceptualization of reality in discourse. This can be easily demonstrated by the noun phrase de blauwe autothe blue car. As claimed above, this noun phrase expresses that the set denoted by the NP blauwe autoblue car contains exactly one member. Since we can safely assume that every language user is aware of the fact that the set denoted by blauwe auto contains an extremely large number of entities, this knowledge is clearly not relevant. Rather, the participants in the discourse have a tacit agreement about which entities are relevant to the discussion at hand; this limited set of entities under discussion is often referred to as the domain of discourse or domain D, which can be assumed to consist of the participants’ shared knowledge about the topic under discussion; de blauwe auto expresses that in this limited domain the set of cars has only one member.

In summary, we have argued that there is no direct relationship between language and reality. Instead, the two domains are only indirectly related through the language user’s internalized conception of the “real world”, and the assignment of truth values is based only on the (correct or incorrect) knowledge encoded in this conception. In conversation, the assignment of truth values is further constrained by domain D, i.e. the knowledge of the participants about the topic under discussion. This view of the relationship between language and reality will be adopted in the discussion in the following sections.