- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This section briefly discusses some general semantic and syntactic properties of quantifiers and the noun phrases in which they occur. Subsection I deals with the core meaning of quantifiers, followed in subsection II by a discussion of the distinction between weak and strong quantifiers. Subsection III discusses the fact that quantifiers behave differently with respect to the kinds of inferences they allow. Subsection IV concludes with a discussion of the independent use of quantifiers, i.e. their use as arguments or floating quantifiers.

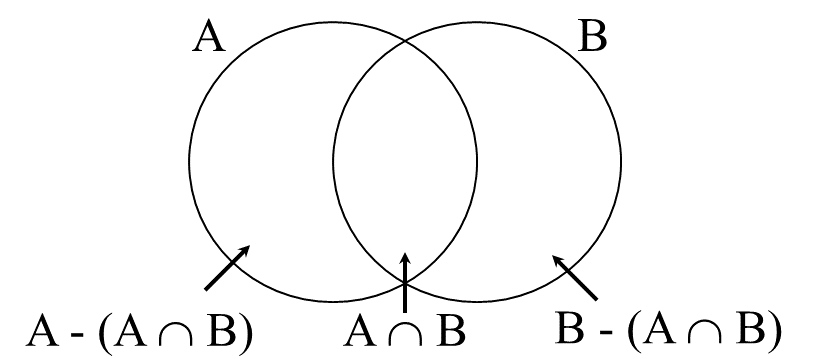

The core meaning of quantifiers in prenominal position can be easily explained by using Figure 1 from Section 15.1.2, sub IIA, repeated below. This figure represents the subject-predicate relation in a clause: set A represents the denotation set of the lexical part (i.e. the NP-part) of the subject, and set B represents the denotation set of the verb phrase, where A and B are both contextually determined, i.e. dependent on the domain of discourse (domain D). The intersection A ∩ B denotes the set of entities for which the proposition expressed by the clause is claimed to be true. For instance, in an example such as Jan wandelt op straat, it is claimed that the set denoted by A, viz. {Jan}, is included in set B, which consists of the people walking in the street. In other words, it is expressed that A - (A ∩ B) is empty.

The quantifiers have a function similar to that of the cardinal numerals; they indicate the size or cardinality of the intersection A ∩ B. They differ from the cardinals, however, in that they often do not do this in a very precise way. For example, an existential quantifier like sommige or enkelesome in (175a) simply indicates that A ∩ B has a cardinality greater than 1. The degree quantifier veelmany in (175b) indicates that the cardinality of A ∩ B is greater than the contextually defined norm n. The universal quantifier alleall in (175c) not only expresses that the intersection of A and B has a cardinality greater than 1, but also that it exhausts set A, i.e. that A - (A ∩ B) is empty.

| a. | Sommige/Enkele | deelnemers | zijn | al | vertrokken. | |

| some/some | participants | are | already | left | ||

| 'Some participants have already left.' | ||||||

| a'. | sommige: |A ∩ B| > 1 |

| b. | Veel deelnemers | zijn | al | vertrokken. | |

| many participants | are | already | left | ||

| 'Many participants have already left.' | |||||

| b'. | veel: |A ∩ B| > n |

| c. | Alle deelnemers | zijn | al | vertrokken. | |

| all participants | are | already | left | ||

| 'All participants have already left.' | |||||

| c'. | alle: |A ∩ B| > 1 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| = 0 |

Because quantifiers perform a similar function as cardinals without making the cardinality of A ∩ B precise, some Dutch grammars refer to these quantifiers as “indefinite cardinal numerals”; other grammars, such as Haeseryn et al. (1997), divide these quantifiers into “indefinite cardinals” and “indefinite pronouns” on the basis of their distribution (i.e. as part of the noun phrase or as an independently used constituent). In the following, we will simply use the term quantifier.

The examples in (175) are all partitive in the sense that set A is already part of domain D, but quantifiers can also be used in presentative sentences, i.e. to introduce new entities into domain D. However, not all quantifiers can be used in this way: for instance, example (176a) shows that the existential quantifiers enkele and sommige differ in that only the former can be used in a presentative expletive construction. This means that the difference between sommige and enkele is similar to the difference between the weak and strong forms of English some, which are given in the glosses as sm and some, respectively. Like enkele, the degree quantifier veelmany can be used in both partitive constructions such as (175b) and presentative expletive constructions such as (176b). The universal quantifier alleall in (176c) cannot be used in presentative sentences. Because the properties of the quantifier in the partitive and presentative constructions correlate with the weak and strong forms of English some, respectively, they are referred to as weak and strong quantifiers.

| a. | Er | zijn | al | enkele/*sommige | deelnemers | vertrokken. | |

| there | are | already | sm/some | participants | left | ||

| 'Some participants have already left.' | |||||||

| b. | Er | zijn | al | veel deelnemers | vertrokken. | |

| there | are | already | many participants | left | ||

| 'Many participants have already left.' | ||||||

| c. | * | Er | zijn | al | alle deelnemers | vertrokken. |

| there | are | already | all participants | left |

The examples in (176) show that noun phrases with weak and strong quantifiers behave like indefinite and definite noun phrases, respectively. There is another way in which this correlation holds. First, consider the two (a)-examples in (177), which show that in noun phrases with a cardinal numeral, the head noun of the primeless example can be left implicit if so-called quantitative er is present (provided that the content of the noun is recoverable from the discourse or extra-linguistic context). However, the acceptability contrast between the two primed examples in (177) shows that this is only possible if the noun phrase is indefinite.

| a. | Jan heeft | drie boeken | meegenomen. | |

| Jan has | three books | prt.-taken | ||

| 'Jan has taken three books with him.' | ||||

| a'. | Jan heeft | er [DP | drie [NP e]] | meegenomen. | |

| Jan has | er | three | prt.-taken |

| b. | Jan heeft | de drie boeken | meegenomen. | |

| Jan has | the three books | prt.-taken | ||

| 'Jan has taken three books with him.' | ||||

| b'. | * | Jan heeft | er [DP | de drie [NP e]] | meegenomen. |

| Jan has | er | the three | prt.-taken |

The examples in (178) show that we find a similar contrast between noun phrases with a weak quantifier and those with a strong quantifier: leaving the head noun implicit is only possible in the former case.

| a. | Jan heeft | er [DP | enkele/*sommige [NP e]] | meegenomen. | |

| Jan has | er | sm/some | prt.-taken | ||

| 'Jan has taken some of them (e.g. books) with him.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | er [DP | veel [NP e]] | meegenomen. | |

| Jan has | er | many | prt.-taken | ||

| 'Jan has taken many of them with him.' | |||||

| c. | * | Jan heeft | er [DP | alle [NP e]] | meegenomen. |

| Jan has | er | all | prt.-taken | ||

| 'Jan has taken all of them with him.' | |||||

For a more detailed discussion of quantitative-er constructions, we refer the reader to Section 20.3.

Quantifiers differ in the logical inferences they allow. High-degree quantifiers such as veelmany, for example, allow the semantic implication in (179a), whereas low-degree quantifiers such as weinigfew do not; the inference actually goes in the opposite direction, in that (179b') implies (179b).

| a. | Veel kinderen | drenzen | en | schreeuwen. ⇒ | |

| many children | whine | and | yell |

| a'. | Veel kinderen | drenzen | en | veel kinderen | schreeuwen. | |

| many children | whine | and | many children | yell |

| b. | Weinig kinderen | drenzen | en | schreeuwen. ⇏ | |

| few children | whine | and | yell |

| b'. | Weinig kinderen | drenzen | en | weinig kinderen | schreeuwen. | |

| few children | whine | and | few children | yell |

Another implicational difference between these two quantifiers is given in (180). If example (180a) is true with the high-degree modifier veelmany, then the same holds for example (180a'), where the VP zwemmento swim denotes a superset of the VP in de zee zwemmento swim in the sea in (180a). In contrast, this implication is not valid in (180b&b'), where the quantifier weinig expresses low degree, since there may be many children swimming in the pool; the inference again goes in the opposite direction, in that (180b') implies (180b).

| a. | Er | zwemmen | veel kinderen | in de zee. ⇒ | |

| there | swim | many children | in the sea | ||

| 'Many children swim in the sea.' | |||||

| a'. | Er | zwemmen | veel kinderen. | |

| there | swim | many children |

| b. | Er | zwemmen | weinig kinderen | in de zee. ⇏ | |

| there | swim | few children | in the sea | ||

| 'Few children swim in the sea.' | |||||

| b'. | Er | zwemmen | weinig kinderen. | |

| there | swim | few children |

These kinds of implications, which have been treated extensively in the formal semantic literature of the last two or three decades, are not limited to quantifiers: example (181) shows, for example, that definite noun phrases behave in essentially the same way as the sentences containing a high-degree modifier.

| a. | De kinderen | drenzen | en | schreeuwen. ⇒ | |

| the children | whine | and | yell |

| a'. | De kinderen | drenzen | en | de kinderen | schreeuwen. | |

| the children | whine | and | the children | yell |

| b. | De kinderen | zwemmen | in de zee. ⇒ | |

| the children | swim | in the sea |

| b'. | De kinderen | zwemmen. | |

| the children | swim |

The semantic properties of quantifiers of the type discussed above have implications for e.g. the licensing of negative polarity elements: a noun phrase containing the quantifier weinigfew can license the negative-polar verb hoevenneed to, whereas a noun phrase containing the quantifier veelmany cannot. Semantic correlations like these have given rise to a vast literature, which will not be discussed here; cf. Zwarts’ (1981) for pioneering work on this topic in Dutch.

| a. | Weinig mensen | hoeven | te vrezen | voor hun baan. | |

| few people | have | to fear | for their job | ||

| 'Few people need to fear losing their job.' | |||||

| b. | * | De/Veel mensen | hoeven | te vrezen | voor hun baan. |

| the/many people | have | to fear | for their job |

So far we have only discussed examples where quantifiers are used as modifiers of a noun phrase. However, a quantifier can also be used as an independent constituent, i.e. as an argument or a floating quantifier. Examples of these uses are given in the primeless and primed examples of (183). The following sections will also discuss these independent uses.

| a. | Allen | gingen | naar | de vergaderzaal. | argument | |

| all[+human] | went | to | the meeting.hall |

| a'. | Ze | zijn | allen | naar de vergaderzaal | gegaan. | floating quantifier | |

| they | are | all[+human] | to the meeting.hall | gone |

| b. | Alle | zijn | uitverkocht. | argument | |

| all[-human] | are | sold.out |

| b'. | Ze | zijn | alle | verkocht. | floating quantifier | |

| they | are | all[-human] | sold |

The examples in (183) show that there are two spellings for the independent occurrences of the quantifiers ending in schwa: with or without a final -n. The presence of this orthographic -n, which is not pronounced in spoken Dutch, depends on the feature [±human] of the referent or associate: the form without -n is used with [-human] nouns, and the form with -n is used with [+human] nouns (cf. Section 20.2.4, sub II, for further discussion). Note that the examples in (183) are all formal and typically found in written language; in colloquial speech, the preferred way of expressing the intended assertions would be in the form of the primed examples, with allemaalall substituted for alle(n)all: Ze zijn allemaal naar de vergaderzaal gegaan/Ze zijn allemaal verkocht.

The examples in (184) show that the universal quantifier alle behaves like the cardinal numerals in that it can be modified by an adverb like bijnaalmost; cf. Section 20.1.1.5. Since this adverb takes only the cardinal in its scope, it seems plausible that they form a phrase. If so, it is unlikely that the cardinal is a functional head occupying the head position Num of NumP. We have therefore concluded that the projection of the cardinal is in the specifier position of NumP, and we can apply a similar analysis to the universal quantifier alle, assuming that it occupies the same position as the cardinal; the determiner D in these structures is the (phonetically empty) indefinite article Ø.

| a. | Marie heeft | bijna vijftig romans van Vestdijk | gelezen. | |

| Marie has | nearly fifty novels by Vestdijk | read | ||

| 'Marie has read nearly fifty novels by Vestdijk.' | ||||

| a'. | [DP D [NumP [bijna vijftig] [Numplural [NP romans van Vestdijk]]]] |

| b. | Marie heeft | bijna alle romans van Vestdijk | gelezen | |

| Marie has | nearly all novels by Vestdijk | read | ||

| 'Marie has read nearly all novels by Vestdijk.' | ||||

| b'. | [DP D [NumP [bijna alle] [Numplural [NP romans van Vestdijk]]]] |

Although the two structural representations in the primed examples look quite similar, there may be a non-trivial difference between them, which is related to the categorial status of the modifier. Section 20.1.1.1 has shown that there are good reasons to assume that cardinal numerals are actually nouns, but similar evidence does not seem to be available for alle, which rather seems to be adjectival in nature. One way to resolve to solve this potential problem is to assume that the two representations are in fact identical, in that the quantifier phrase is headed by a silent counterpart of the cardinal, number. If so, the representation in (184b') should be replaced by the one in (185a). An attractive argument for this analysis is that the silent noun number can be replaced by the cardinal tweeënvijftigfifty-two (the actual number of novels that Vestdijk wrote) without any change in the truth value of the sentences.

| a. | [DP D [NumP | [bijna alle number] [Numplural [NP | romans van Vestdijk]]]] | |

| [DP D [NumP | nearly all | novels by Vestdijk |

| b. | [DP D [NumP | [bijna alle tweeënvijftig] [Numplural [NP | romans van Vestdijk]]]] | |

| [DP D [NumP | nearly all fifty-two | novels by Vestdijk |

If viable, the analyses in (185) can easily be extended to cases such as (186a), which would then be assigned the representation in (186b); recall from Section 20.1.1.6, sub V, that Kayne (2003; 2007) also advocates such an analysis for English few (among other cases).

| a. | Marie heeft | erg veel/weinig | romans van Vestdijk | gelezen. | |

| Marie has | very many/few | novels by Vestdijk | read |

| b. | [DP D [NumP [erg weinig number] [Numplural [NP romans van Vestdijk]]]] |

The hypothesis proposed here will be adopted in the following sections. The modification of quantifiers will be discussed in more detail in Section 20.2.5.