- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This section examines some meaning aspects contributed by the possessive pronouns. Subsection I argues that the meaning of the referential possessive pronouns is very close to that of the definite articles, but in addition there is a partitioning of the denotation set of the head noun (or its lexical projection NP, but we will stick to the simple cases here). This last part of the meaning can also be found in the other semantic types of possessive pronouns. Subsection II discusses the semantic relationship between the possessive pronoun and the referent of the noun phrase that causes this partitioning: in the case of zijn boekhis book, for example, this relationship can be one of ownership, authorship, and probably many others.

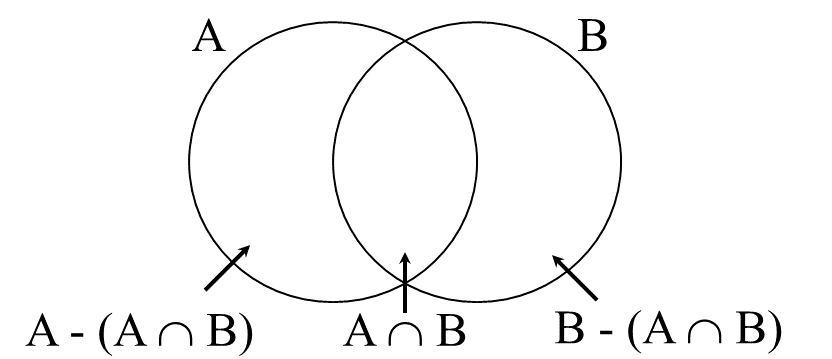

Section 19.2.2.1 has shown that possessive pronouns are in complementary distribution with articles, and we have used this fact to motivate the claim that they function as determiners of the noun phrase. Another reason for this claim is that possessive pronouns also share certain semantic properties with articles. This is most obvious in the case of referential possessive pronouns, which contribute more or less the same meaning as the definite articles. Consider Figure 1, where A represents the denotation set of the lexical part (i.e. the NP-part) of the subject and B represents the set of entities denoted by the verb phrase, where A and B are both contextually determined, i.e. dependent on the domain of discourse (domain D). The intersection A ∩ B denotes the set of entities for which the proposition expressed by the clause is claimed to be true.

Section 19.1.1.1 has argued that the core meaning of the definite article is that all entities in domain D which satisfy the description of the NP-part of the subject are included in the intersection A ∩ B, i.e. that the remainder of set A is empty; cf. (463a'). The referential possessive pronoun zijnhis in (463b) expresses a similar meaning, but additionally introduces a partitioning of set A: the assertion is not about all entities that satisfy the description of the NP, but about a subset Asub that stands in a certain relation to the referent of the possessive pronoun. Of course, the fact that the possessive pronouns imply a partitioning of set A does not necessarily imply that set A is a non-singleton set. If domain D contains only one book, the speaker can still use the noun phrase mijn boekmy book; in this case the evoked alternative referent set is empty.

| a. | De boeken | verkopen | goed. | |

| the books | sell | well |

| a'. | de NPpl: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| = 0 |

| b. | Zijn boeken | verkopen | goed. | |

| his books | sell | well |

| b'. | zijn NPpl: |Asub ∩ B| ≥ 1 & |Asub ‑ (Asub ∩ B)| = 0 |

Note that the relationship in question need not be one of possession, but can be of various kinds, and is largely determined by the non-linguistic context; cf. Janssen (1976:§3.1) for a relevant discussion. The referent of the possessive pronoun in (463b) may be the author or publisher of the books, but also someone who edited them or made a guess about which books would sell well.

It is not only the core meaning of the definite articles that is associated with referential possessive pronouns; other properties of definite noun phrases can also be found in noun phrases containing a referential possessive pronoun. For example, both types of noun phrases usually refer to entities in domain D that are assumed to be uniquely identifiable by the speaker; a question such as (464a) presupposes that the listener is able to identify the referent of the noun phrase mijn sleutels. And just as in the case of the definite article, noun phrases with a referential possessive pronoun can introduce new entities into domain D that are somehow anchored to a known entity in domain D. An example such as (464b) does not presuppose that the listener knows who Jan’s wife is, but that the mention of Jan is sufficient to anchor the referent of the noun phrase zijn vrouwhis wife to someone related to him.

| a. | Heb | je | mijn sleutels | misschien | gezien? | |

| have | you | my keys | maybe | seen | ||

| 'Did you by any chance see my keys?' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | zag | Jan daarnet. | Zijn vrouw | ligt | in het ziekenhuis. | |

| I | saw | Jan just.now | his wife | lies | in the hospital | ||

| 'I saw Jan just now. His wife is in the hospital.' | |||||||

Noun phrases with a referential possessive pronoun, like definite noun phrases, also exhibit exceptions to the general requirement that the noun phrase be uniquely referring. For example, if the noun phrase refers to a body part, like a leg or a hand, the noun phrase may be singular, leaving some vagueness as to which of the (two) hands or legs is meant; cf. example (465a). Something similar occurs with kinship nouns; an example such as (465b) does not imply that the speaker has only one nephew; apparently it is not the referent that matters here, but the relationship between the speaker and the person referred to. A similar case with a non-kinship noun is given in (465c), which expresses that the train the speaker took was delayed.

| a. | Jan schopte | tegen mijn been. | |

| Jan kicked | against my leg |

| b. | Mijn neef | is ziek. | |

| my nephew | is ill | ||

| 'My nephew is ill.' | |||

| c. | Mijn trein | had | weer eens | vertraging. | |

| my train | had | again once | delay | ||

| 'My train was delayed once again.' | |||||

Because of the overlap in meaning between referential possessive pronouns and definite articles, the noun phrases introduced by a possessive pronoun in the primeless examples of (466) are virtually synonymous with the noun phrases in the primed examples with a definite article and a postnominal possessive van-PP. This suggests that, apart from their reference, the meaning of the referential possessive pronouns in the primeless examples consists of two parts corresponding to the meaning of the definite article and the modifying van-phrase in the primed examples: the first part involves definiteness, and the second part involves the partitioning of the set denoted by the head noun into two subsets, namely a subset that is in the relevant semantic relation with the referent of the possessive pronoun and a subset that is not.

| a. | mijn/jouw/zijn | boek | |

| my/your/his | book |

| a'. | het boek | van mij/jou/hem | |

| the book | of me/you/him |

| b. | ons/jullie/hun | boek | |

| our/your/their | book |

| b'. | het boek | van ons/jullie/hen | |

| the book | of us/you/them |

Since referential possessive pronouns are inherently definite, possessed indefinite noun phrases usually involve the presence of an indefinite article and a postnominal possessive van-PP, as in (467). As always, the indefinite article expresses that the intersection A ∩ B has cardinality 1, without any implication for the remainder of set A, i.e. A - (A ∩ B) may or may not be empty.

| a. | een boek | van mij/jou/hem/haar | |

| a book | of me/you/him/her | ||

| 'a book of mine/yours/his' | |||

| b. | een boek | van ons/jullie/hen | |

| a book | of us/you/them | ||

| 'a book of ours/yours/theirs' | |||

For completeness’ sake, note that the complement of the preposition van is a personal object pronoun and not, as in English, an (inflected) possessive pronoun as in a book of mine/yours/his/hers.

Example (468a) shows that indefiniteness can also be inherited from the existentially quantified possessive pronoun iemandssomeoneʼs. That the whole noun phrase is indefinite is clear from the fact that the noun phrase iemands auto can occur in the expletive er-construction. The possessive pronoun in this example again introduces a partitioning of set A, but the speaker leaves open which subset of A is meant. The universal possessive pronoun also introduces a partitioning of set A, but now it is claimed that all subsets of A are subsets of B. As a result (468b) expresses more or less the same thing as the simpler sentence De/Alle auto’s staan verkeerd geparkeerdThe/All cars are wrongly parked, which perhaps explains why (468b) feels a little tortuous.

| a. | Er | staat | iemands auto | verkeerd | geparkeerd. | |

| there | stands | someone’s car | wrongly | parked | ||

| 'Someone's car is wrongly parked.' | ||||||

| b. | Ieders auto | staat | verkeerd | geparkeerd. | |

| everyone’s car | stands | wrongly | parked | ||

| 'Everyoneʼs car is wrongly parked.' | |||||

The reciprocal form elkaarseach otherʼs and the interrogative and relative form wienswhose also introduce a partitioning of the denotation set of the nominal head of their noun phrases. In (469a), the cardinality of the antecedent of the possessive pronoun is equal to the cardinality of the relevant subset of the denotation set of opstel, and the members of the antecedent and the relevant subset are reciprocally related: set A consists of three essays, each written by a different pupil, and each of the pupils admires the essays written by the other two pupils. Question (469b) can be used when the set of books is divided into subsets defined by e.g. ownership, and the speaker asks about a particular subset of books. The relative construction in (469c) allows the addressee to pick out the intended referent of the complete noun phrase on the basis of a contextually determined partitioning of the books.

| a. | Die drie leerlingen | bewonderen | elkaars | opstel. | |

| those three pupils | admire | each.other’s | essay |

| b. | Wiens boeken | zijn | dit? | |

| whose books | are | these |

| c. | de man | wiens boeken | ik | gelezen | heb | |

| the man | whose books | I | read | have |

For completeness, the examples in (470) show that noun phrases headed by interrogative wiens are weak indefinites, while noun phrases headed by demonstrative wiens are strong. This is clear from the fact that only (470a) can occur in expletive er-constructions; er in (470b) is only possible if it is given a locative interpretation.

| a. | Wiens auto | staat | er | voor de deur? | |

| whose car | stands | there | in.front.of the door | ||

| 'Whose car is in front of the door.' | |||||

| b. | de man | [wiens auto | (#er) | voor de deur staat] | |

| de man | whose car | there | in.front.of the door | ||

| 'the man whose car is in front of the door' | |||||

The possessive pronouns owe their name to the fact that in many cases they refer to the owner of the referent of the complete noun phrase; the noun phrase mijn boekmy book typically refers to a book owned by the speaker. However, the term possessive pronoun (or, more generally, possessive noun phrase) is a misnomer, because the relation between the pronoun’s referent and the referent of the complete noun phrase need not be restricted to possession; the noun phrase mijn boek can also involve a relation of authorship. In the following subsections we will briefly discuss two systematic kinds of relation that the referent of a possessive pronoun and the referent of the complete noun phrase of which it is a part can enter into. The discussion in the following subsections is not intended to be exhaustive, as the creative powers of language users far exceed our descriptive potential.

In a sense, the relation expressed between the referent of the possessive pronoun/noun phrase (henceforth: possessor) and the referent of the full noun phrase in (471a) could be described as a relation of possession. The more general interpretation, however, is that there is a relation of kinship between the possessor and the referent of the full noun phrase. From the use of the noun moeder it can be inferred that there must be a daughter or a son, and (471a) expresses that the possessor is in this kinship relation to the referent of the full noun phrase; cf. Section 16.2.2. Examples such as (471b), which expresses that the referent of the proper noun is part of the addressee’s family, probably fall into the same category; this use of the possessive pronoun is particularly common when referring to family members, dear friends, or favorite pets, even in cases where the proper noun alone would have sufficed for identification.

| a. | zijn/Jans | moeder | |

| his/Jan’s | mother |

| b. | jullie | Jan | |

| yourpl | Jan |

That noun phrases with a possessor can be truly ambiguous between the possession reading and a reading involving an implied relationship can be seen from the examples in (472). Since a house typically evokes the idea of an occupant, the implied relation is that the referent of the possessive pronoun lives in the house in question, whereas on the possession reading this person is actually the owner of the house. Example (472a) is only compatible with the inferred reading, whereas (472b) is compatible with the true possession reading (and it may also be compatible with the inferred reading, in which case Jan is subletting the house).

| a. | Jan huurt | zijn huis | van een Amerikaan. | |

| Jan rents | his house | from an American |

| b. | Jan verhuurt | zijn huis | aan een Amerikaan. | |

| Jan rents.out | his house | to an American |

A special case of the inferred relation is the case in which the possessive pronoun/noun phrase can enter into a thematic relation with the head noun. This is especially clear with deverbal nouns like behandelingtreatment, which is derived from and inherits the thematic structure of the transitive verb behandelento treat; cf. Section 16.2.3. Consider the examples in (473). In (473b) it is shown that the agentive argument of the verb behandelen can appear as a prenominal possessor in the noun phrase. When there is no postnominal van-PP, as in (473c), the prenominal possessor can be interpreted as expressing the agent or the theme.

| a. | Zij/MarieAgent | behandelt | hem/PeterTheme. | |

| she/Marie | treats | him/Peter | ||

| 'She/Marie is treating him/Peter.' | ||||

| b. | haar/MariesAgent | behandeling | van hem/PeterTheme | |

| her/Marie’s | treatment | of him/Peter |

| c. | zijn/PetersAgent/Theme | behandeling | |

| his/Peter’s | treatment |

For non-derived nouns, the possessor can also be an argument of the noun. Example (471a) above, which concerns a kinship noun, can actually be used to illustrate this: the noun moedermother selects an argument that is in a parent-child relation with the referent of the noun phrase. Other nouns that typically have this property are the so-called picture nouns like fotophoto in (474); cf. Section 16.2.5. The prenominal possessor in (474b) can be interpreted as the maker of the picture, i.e. with a similar semantic role as the subject of the sentence in (474a). When the postnominal van-PP is absent, as in the (c)-examples, the prenominal possessor can be interpreted either as the maker or as the person depicted. Of course, the prenominal elements in (474b&c) can also refer to the possessor of the photograph in question.

| a. | Zij/MarieAgent | maakt | een foto | van hem/PeterTheme. | |

| she/Marie | makes | a photo | of him/Peter | ||

| 'She/Marie is making a picture of him/Peter.' | |||||

| b. | haar/MariesAgent | foto | van hem/PeterTheme | |

| her/Marie’s | photo | of him/Peter |

| c. | haar/MariesAgent | foto | |

| her/Marie’s | photo |

| c'. | zijn/PetersTheme | foto | |

| his/Peter’s | photo |

For our present purposes, the examples in (473) and (474) will suffice. For a more detailed discussion of the thematic structure of nouns and the semantic roles that prenominal possessors may have, see Chapter 16.