- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This section discusses sequences such as zowel ... als ...both ... and ..., of ... of ...either ... or ..., and noch ... nochneither ... nor ..., which are traditionally analyzed as complex coordinators; although we will see that this may not be correct, we will take this analysis as the starting point of our discussion and therefore refer to these sequences as correlative coordinators. The examples in (500) illustrate that these complex coordinators are characterized by their discontinuity, in that they consist of at least two members: the first member of these sequences appears before the first coordinand, while the second one appears before of all later coordinands. We will refer to the two members as the initial and non-initial part of the entire coordinate structure, which will be called the correlative coordinate structure.

| a. | Zowel | Marie | als | Peter | (is ziek). | |

| both | Marie | and | Peter | is ill |

| b. | Zowel Marie | als Jan | als Peter | (is ziek). | |

| both Marie | and Jan | and Peter | is ill |

There are also sequences for which there is less agreement as to whether they should be considered as correlative coordinators. We take the list in (501) from Haeseryn et al. (1997) as our starting point (a longer list could be compiled on the basis of Paardekooper 1986, section 7.1), but we will see that there are reasons for eliminating various forms from this set.

| Correlative coordinators (to be revised): en ... en ... ‘as well as’, #evenmin ... als ... ‘neither ... nor ...’, #hetzij ... hetzij/of ‘either ... or ...’, noch ... noch ... ‘neither ... nor ...’, of ... of ... ‘either ... or ...’, ofwel ... ofwel ... ‘or ... or ...’, #(net) zomin ... als ... ‘neither ... nor ...’, zowel ... als ... ‘both ... and ...’ |

The forms marked with a number sign are given by Haeseryn et al. as formal, but Table 20 shows that most forms are very rare and hardly occur in speech at all; the frequencies in this table are taken from Uit den Boogaart (1975) and include all cases in which the initial form is marked as “introductory part of a coordinate structure” (code 740). The most frequent form is zowel ... als ...both ... and ..., but even the frequency of this sequence is negligible compared to the frequencies of simplex enand (14592 in writing/3650 in speech), ofor (1686/452), and maarbut (3224/1437) in the same corpus. Table 20 thus strongly suggests that correlative coordinators are characteristic of written texts and formal speech, and therefore should not be considered as a part of core grammar. We will nevertheless discuss these elements, since they have received a fair amount of attention in the linguistic literature, and postpone further discussion of the question of whether correlative coordinators are part of the core syntax to Subsection III.

| correlative coordinator | writing | speech |

| en ... en ... ‘as well as’ | 4 | 1 |

| #evenmin ... als ... ‘neither ... nor ...’ | 0 | 0 |

| #hetzij ... hetzij/of ... ‘either ... or ...’ | 10 | 1 |

| noch ... noch ... ‘neither ... nor ...’ | 18 | 1 |

| of ... of ... ‘either ... or ...’ | 34 | 2 |

| #ofwel ... ofwel ... ‘or ... or ...’ | 0 | 0 |

| #(net) zomin ... als ... ‘neither ... nor ...’ | 0 | 0 |

| zowel ... als ... ‘both ... and ...’ | 127 | 2 |

Grammars and individual linguists tend to define the set of correlative coordinators in an enumerative way, which is undesirable because it can lead to a quite bewildering description of (coordinate structures with) these elements. Subsection I will therefore examine to what extent the sequences in (501) have the defining property of simplex coordinators, i.e. that they are external to the coordinands: the forms that do not have this property will be excluded from this set. Subsection II examines a number of properties of the remaining forms. Finally, Subsection III discusses the syntactic representation of correlative coordinate structures. Our review will show that there is a steadily growing consensus in the theoretical literature that the initial part should not be considered as a subpart of a correlative coordinator but has a more special status; if this line of investigation is on the right track, it may lead to the conclusion that the notion of correlative coordinator is a misnomer resulting from an incorrect syntactic analysis.

There seems to be no generally accepted definition of the term correlative coordinator. Haeseryn et al. (1997), for instance, simply present the list in (501) as established, and take it as their point of departure for the description of the properties of this type of coordinators without any discussion. This method is undesirable; instead, we will take the view that correlative coordinators should at least satisfy the criterion met by all simplex coordinators, i.e. that they are external to the coordinands. This will lead to a reduction of the list in (501).

Correlative coordinators can easily be confused with correlative adverbial phrases such as enerzijds ... anderzijds ...on the one hand ... on the other (hand) ... and niet alleen ... ook ...not only ... also .... The crucial difference is that correlative coordinators are external to the coordinands, whereas correlative adverbials are part of them. This can be easily illustrated by means of clausal coordinands: in (502a), the initial positions of the coordinated main clauses (in square brackets) are occupied by their subjects, which means that the two parts of the correlative coordinator en ... en ... are clause-external; in (502b), on the other hand, the initial positions are occupied by the correlative adverbial phrases, as can be seen from the fact that they trigger subject-verb inversion. Note that in (502b) we are dealing with an asyndetic construction, but that it is possible to replace the phonetically empty coordinator by the coordinator maarbut.

| a. | En | [de schatkist | is leeg] | en | [de werkeloosheid | neemt | toe]. | |

| and | the treasury | is empty | and | the unemployment | increases | prt. | ||

| 'And the treasury is empty and the unemployment increases.' | ||||||||

| b. | [Niet alleen | is de schatkist leeg] Ø | [ook neemt | de werkeloosheid | toe]. | |

| not only | is the treasury empty | also increases | the unemployment | prt. | ||

| 'Not only is the treasury empty, the unemployment also increases.' | ||||||

One problem with applying the word order test in (502) is that not all correlative coordinators can link main clauses, as shown in (503a) for zowel ... als ...both .... and .... However, example (503b) shows that the two parts of the correlative coordinator cannot occupy the initial positions of the coordinated clauses either, providing somewhat weaker evidence for the claim that they are not clausal constituents.

| a. | * | Zowel | [de schatkist is leeg] | als | [de werkeloosheid | neemt | toe]. |

| both | the treasury is empty | and | the unemployment | increases | prt. |

| b. | * | [Zowel | is de schatkist leeg] Ø | [als | neemt | de werkeloosheid | toe]. |

| both | is the treasury empty] | also | increases | the unemployment | prt. |

Nevertheless, it has been claimed that there is reason for assuming adverbial status for the initial part of the correlative coordinator, zowel: Haeseryn et al. (1997:1515), for instance, claim that it can penetrate into the first coordinand. This claim is crucially based on their assumption that (504b) involves conjunction reduction (indicated by strikethrough). We have marked the structure in (504b) with an asterisk because the analysis suggested by Haeseryn et al. is highly problematic in light of the fact that the deleted part cannot be realized overtly; a more natural alternative analysis would be that we are simply dealing with coordination of PP-modifiers, as indicated in (504b').

| a. | [Zowel | de antwoorden van Marie | als | de antwoorden van Jan] | zijn fout. | |

| both | the answers of Marie | and | the answers of Jan | are wrong | ||

| 'Both Marie's answers and Jan's answers] are wrong.' | ||||||

| b. | * | [De antwoorden | zowel van Marie | als | de antwoorden van Jan] | zijn fout. |

| the answers | both of Marie | and | the answers of Jan | are wrong |

| b'. | De antwoorden | [zowel van Marie | als | van Jan] | zijn fout. | |

| the answers | both of Marie | and | of Jan | are wrong |

It should also be noted that some speakers consider the order in the (b)-examples to be marked compared to (504a). This order is even more degraded when the noun is singular: (505b) is at best marginally acceptable when the string zowel van Marie als van Jan is parenthetical, i.e. preceded and followed by an intonation break. The unacceptability of (505b) on the non-parenthetical reading would be unexpected in a conjunction reduction analysis, which should therefore be rejected.

| a. | [Zowel | het antwoord van Marie | als | het antwoord van Jan] | is fout. | |

| both | the answer of Marie | and | the answer of Jan | is wrong | ||

| 'Both Marie's answer and Jan's answer] are wrong.' | ||||||

| b. | * | [Het antwoord | zowel van Marie | als | van Jan] | is fout. |

| the answers | both of Marie | and | of Jan | is wrong |

Note in passing that Neijt (1979:6-7) has shown that examples such as (504b') are impossible with other correlative coordinate structures: replacing zowel ... als ... by en ... en ...and ... and ..., of ... of ...either ... or ..., or noch ... noch ...neither ... nor ... leads to severely degraded results (on the intended, non-parenthetical reading). Again, this is unexpected in a conjunction reduction analysis. Haeseryn et al. (1997:1517) also provide a conjunction reduction analysis for example (506a), with coordination of main clauses (CPs). An alternative analysis would involve coordination of verbal predicates (VPs), as indicated in (506b).

| a. | [[CP | Jan | zal | zowel | de rozen | snoeien] | als [CP | Jan zal | de tulpen | planten]]. | |

| [[CP | Jan | will | both | the roses | prune | and | Jan will | the tulips | plant | ||

| 'Jan will both cut back the roses and plant the tulips.' | |||||||||||

| b. | Jan | zal | [zowel [VP | de rozen | snoeien] | als [VP | de tulpen | planten]]. | |

| Jan | will | both | the roses | prune | and | the tulips | plant |

The conjunction reduction approach suggested by Haeseryn et al. is again problematic because it cannot account for the unacceptability of example (507a), since the (presumed) clausal coordinands are both syntactically well-formed. The VP-coordination analysis, on the other hand, fares better here because example (507b) is unacceptable for two reasons: (i) the finite verb snoeit has been extracted from the first VP-coordinand by verb-second in violation of the coordinate structure constraint discussed in Section 38.3, sub II, and (ii) the finite verb plant in the second coordinand cannot undergo verb-second at all because the verb-second position is already occupied by snoeit. That the unacceptability of (507a&b) should be accounted for in terms of verb-second is supported by the fact that their embedded counterpart (without verb-second) in (507c) is fully acceptable; cf. Neijt (1979:7ff.).

| a. | * | [[CP | Jan | snoeit | zowel | de rozen] | als [CP | Jan | plant | de tulpen]]. |

| * | [[CP | Jan | prunes | both | the roses | and | Jan | plants | the tulips |

| b. | * | Jan | snoeit | [zowel [VP | de rozen tv] | als [VP | de tulpen | plant]]. |

| Jan | prunes | both | the roses | and | the tulips | plants |

| c. | dat | Jan | [zowel [VP | de rozen | snoeit] | als [VP | de tulpen | plant]]. | |

| that | Jan | both | the roses | prunes | and | the tulips | plants |

The discussion above has shown that the two parts of correlative coordinators must be external to the coordinands. This casts doubt on the generally accepted claim that noch ... noch ...neither ... nor ... is a correlative coordinator. The examples in (508) show that the two occurrences of noch are internal to the clausal coordinands: the (a)-examples show that noch obligatorily triggers subject-verb inversion and (508b) shows that noch can even occur in the middle field of the first clause.

| a. | [[Noch | zal | hij | de rozen | snoeien], Ø | [noch | zal | hij | de tulpen planten]]. | |

| neither | will | he | the roses | prune | nor | will | he | the tulips plant | ||

| 'Neither will he prune the roses, nor will he plant the tulips.' | ||||||||||

| a'. | * | Noch | [hij | zal | de rozen | snoeien], | noch | [hij | zal | de tulpen | planten]. |

| neither | he | will | the roses | prune | nor | he | will | the tulips | plant |

| b. | [[Hij zal | noch | de rozen | snoeien], Ø | [noch | zal | hij | de tulpen planten]]. | |

| he will | neither | the roses | prune | nor | will | he | the tulips plant | ||

| 'Neither will he prune the roses, nor will he plant the tulips.' | |||||||||

The examples in (508) thus conclusively show that noch ... noch ... can be used as a correlative adverbial, which need not surprise us, since Section 38.3, sub IIIG, has already shown that noch can be used as an adverbial with the meaning (en) nietand not. Of course, it is not the case that these examples provide conclusive proof that the sequence noch ... noch ... cannot occur as a correlative coordinator in other contexts: the unacceptability of (508a') may simply be due to some idiosyncratic restriction on the coordinands of correlative noch ... noch ... It will be clear, however, that the burden of proof is on those who wish to maintain the traditional analysis. Those who reject this analysis cannot rest their case either, since they should provide a better alternative for cases such as Ik heb noch Jan noch Marie gezienI have seen neither Jan nor Marie, in which noch ... noch ... seems to behave as a coordinator. We will return to this issue in Subsection III.

Haeseryn et al. (1997:1517) claim that the intended meaning of the unacceptable example in (507a) can be expressed by example (509a). They rate this example as fully acceptable, but our informants rate it as unacceptable, or at least quite marked, and the same holds for example (509b), which is claimed to occur alongside (506a). The examples in (509) are regularly cited in the literature as counterexamples to the generalization that the coordinands in a coordinate structure must be of the same kind in the sense formulated in Section 38.3, sub I.

| a. | % | Jan snoeit | zowel de rozen | als dat hij de tulpen plant. |

| Jan prunes | both the roses | and that he the tulips plants |

| b. | % | Jan zal | zowel | de rozen | snoeien | als | dat hij de tulpen | zal | planten. |

| Jan will | both | the roses | prune | and | that he the tulips | will | plant | ||

| 'Jan will both cut back the roses and plant the tulips.' | |||||||||

We believe that theoretical claims based on these marked, constructed examples should be approached warily: we would be happy to assume that they are not part of the core syntax and should be regarded as a quirk of the formal register, i.e. as a relic of the older adverbial use of zowel als as described in the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (item Zoowel, sub 1); see also Van Zonneveld (1992:340).

The examples in (510) show that similar structures with even min/(net) zo min ... als ...neither ... nor ... seem acceptable (although some speakers object to (510b), which we have indicated with the percent sign). However, there is no a priori reason for analyzing these sequences as coordinators; an adverbial analysis may also be viable, since that they have the form of an equative; cf. even/(net) zo aardig als ...(just) as kind as; we will return to this in Chapter 40. Note in passing that, for this reason, we will not follow the orthographical rule that that even min and zo min are written as single words; elsewhere, when their status as head/phrase is not at issue, we do follow the orthographical rule.

| a. | Jan zal | even min | de rozen | snoeien | als | dat hij de tulpen | zal | planten. | |

| Jan will | neither | the roses | prune | als | that he the tulips | will | plant | ||

| 'Jan will neither cut back the roses nor plant the tulips.' | |||||||||

| b. | % | Jan zal | zo min | de rozen | snoeien | als | dat hij de tulpen | zal | planten. |

| Jan will | neither | the roses | prune | als | that he the tulips | will | plant | ||

| 'Jan will neither cut back the roses nor plant the tulips.' | |||||||||

We also have good empirical reasons for excluding even min/zo min ... als ... from the set of correlative coordinators and for analyzing them as ordinary adverbially used equatives of the form even/zo A als ...as A as. First, note that zo min is typically modified by the degree modifier netjust as, which is impossible for a coordinator but common for adjectives premodified by zoas; cf. net zo aardig (als)just as nice (as).

| a. | Jan zal | (*net) | zowel | de rozen snoeien | als | de tulpen | planten. | |

| Jan will | just.as | both | the roses prune | als | the tulips | plant |

| b. | Jan zal | net | zo min | de rozen snoeien | als | de tulpen | planten. | |

| Jan will | just.as | neither | the roses prune | als | the tulips | plant |

Second, if we were dealing with correlative coordinators, we would expect the als-part to be obligatory; the cases in (512) show that this is borne out by zowel ... als ... but not by even min/zo min ... als ...; just as in the case of even/net zo aardigjust as kind the als-part can be omitted if its content can be reconstructed from the context.

| a. | * | Jan zal | zowel | de rozen | snoeien. |

| Jan will | both | the roses | prune |

| b. | Jan zal | even min/net zo min | de rozen | snoeien. | |

| Jan will | neither/neither | the roses | prune |

Third, we have seen in Subsection A that the two parts of the correlative coordinator zowel ... als ... cannot occupy the initial position of clausal coordinands. Example (513b) shows, however, that this is possible for the initial part of the supposed coordinators even min/zo min ... als ... The fact that even min and net zo min trigger subject-verb inversion shows that they are clausal constituents.

| a. | * | Zowel | zal | Jan de rozen | snoeien | (als | de tulpen | planten). |

| both | will | Jan the roses | prune | als | the tulips | plant |

| b. | Even min/Net zo min | zal | Jan de rozen | snoeien. | |

| neither/neither | will | Jan the roses | prune | ||

| 'Jan will not cut back the roses either' | |||||

Fourth, example (514b) shows that even min/zo min ... als ... would be unique among coordinators in being unable to coordinate nominal phrases. The intended meaning can be expressed by (514b'), but in such cases even min/zo min als-phrases clearly have an independent adverbial function. The (a)-examples show that zowel ... als ... again exhibits exactly the opposite behavior.

| a. | [Zowel | Jan | als | Peter] | zal | de rozen | snoeien. | |

| both | Jan | and | Peter | will | the roses | prune |

| a'. | * | Jan zal | zowel | als Peter | de rozen | snoeien. |

| Jan will | both | and Peter | the roses | prune |

| b. | * | [Even min/net zo min | Jan als | Peter] | zal | de rozen | snoeien. |

| neither/neither | Jan als | Peter | will | the roses | prune |

| b'. | Jan zal | even min/net zo min | als | Peter | de rozen | snoeien. | |

| Jan will | neither/neither | als | Peter | the roses | prune | ||

| 'That Jan will no more prune the roses than Peter.' | |||||||

The claim that the even min/zo min als-phrase in (514b') has an independent syntactic function seems uncontroversial, since Haeseryn et al. (1997:1517) provide the same analysis for similar examples. They also analyze net zo min ... als Peter in example (515b) as adverbial. This analysis can be supported by the fact that net zomin in (515b) can be replaced by other degree adverbials, as shown by Jan is net zo goed/zeer een schurk als PeterJan is just as good a scoundrel as Peter; a similar replacement of zowel is never possible, probably because it is a single word.

| a. | * | Jan is | zowel | een schurk | als Peter. |

| Jan is | both | a scoundrel | as Peter |

| b. | Jan is | net zomin | een schurk | als Peter. | |

| Jan is | just as.less | a scoundrel | as Peter | ||

| 'Jan is no more a scoundrel than Peter.' | |||||

The (b)-examples in (511) to (515) all provide evidence for the claim that even min and zo min are clausal constituents; therefore it seems safe to conclude that even min/zo min ... als ... are not correlative coordinators, but should be analyzed as adverbially used equatives of the form even/zo A als ...as A as. The fact that the (a)-examples show that zowel ... als ... behaves systematically differently can be taken as evidence for analyzing it as a true correlative coordinator. Readers interested in further discussion of the internal structure of even min/zo min ... als ... phrases are referred to Section 40.1, sub I.

This subsection has examined the set of putative correlative coordinators in (501) from the point of view that such coordinators are like simplex coordinators in that they are external to their coordinands. This has led to the conclusion that the two members of the sequence noch ... noch ... should be analyzed as adverbial phrases in the case of clausal coordination; nevertheless, we will not exclude this sequence from the list in (501) for the simple reason that noch ... noch ... may still function as a correlative coordinator in other contexts. We will exclude the sequences even min/zo min ... als ... from the list because there is compelling evidence that these are not correlative coordinators but adverbially used equatives of the form even/zo A als ...as A as. The result of all this is the reduced list in (516).

| Correlative coordinators: en ... en ... ‘as well as’, #hetzij ... hetzij/of ‘either ... or ...’, noch ... noch ... ‘neither ... nor ...’, of ... of ... ‘either ... or ...’, ofwel ... ofwel ... ‘or ... or ...’, zowel ... als ... ‘both ... and ...’ |

This subsection discusses the four most common correlative coordinators: en ... en ...as well as, noch ... noch ...neither ... nor ..., of ... of ...either ... or ..., and zowel ... als ...both ... and .... The two remaining forms hetzij ... hetzij/ofeither ... or ... and ofwel ... ofwel ...or ... or ... will only be discussed insofar as they exhibit behavior markedly distinct from that of of ... of ....

One of the characteristic properties of the correlative coordinator en ... en ...and ... and ... is that its initial and non-initial parts are accented, which is why it is often written with an accent: Ik heb én Jan én Marie gezienI have seen and Jan and Marie. This subsection will show that coordinate structures with correlative en ... en ... differ from those with simplex en in that they (i) exhibit additional restrictions on the coordinands, (ii) cannot be interpreted cumulatively, and (iii) exhibit special agreement properties.

The examples in (517) show that the correlative en .. en ... behaves like simplex en in that it can link clauses (CPs), noun phrases (DPs), APs, and PPs.

| a. | [En | Jan is ziek | en | Marie gaat op vakantie]. | CPs | |

| and | Jan is ill | and | Marie goes on vacation |

| b. | [En | de man | en | de vrouw] | zingt | een lied. | DPs | |

| and | the man | and | the woman | sings | a song |

| c. | Jan is | [en | ziek | en | moe]. | APs | |

| Jan is | and | ill | and | tired |

| d. | Jan werkt | [en | in Amsterdam en | in Utrecht]. | PPs | |

| Jan works | and | in Amsterdam and | in Utrecht |

The correlative and simplex forms differ, however, in that the former links only declarative main clauses: linking interrogative (Q), imperative (Imp) or exclamative (Excl) clauses leads to a degraded result; see also Neijt (1979:16). For comparison, consider the corresponding examples with simplex enand in Section 38.4.1, sub IA1.

| a. | * | [En | is Jan ziek | en | gaat Marie op vakantie]? | yes/no-Q |

| and | is Jan ill | and | goes Marie on vacation |

| a'. | * | [En | wie | is er | ziek | en | wie | gaat | er | op vakantie]? | wh-Q |

| and | who | is there | ill | and | who | goes | there | on vacation |

| b. | * | [En | neem | een maand | vrij | en | ga | op vakantie]! | Imp |

| and | take | a month | off | and | go | on vacation |

| c. | * | [En | wat | draagt | Jan een mooi horloge | en | wat | heeft | Els een prachtige ring | aan haar vinger]! | wh-excl |

| and | what | wears | Jan a beautiful watch | and | what | has | Els a splendid ring | on her finger |

Dependent declarative and interrogative clauses, on the other hand, behave alike in that they both can be conjoined; imperatives are excluded for the independent reason that they cannot be embedded at all.

| a. | Els zei | [en | dat | Jan ziek | is | en | dat | Marie op vakantie gaat]. | Decl | |

| Els said | and | that | Jan ill | is | and | that | Marie on vacation goes | |||

| 'Els said both that Jan is ill and that Marie is going on vacation.' | ||||||||||

| b. | Els vroeg | [en | of | Jan ziek | is en | of | Marie op vakantie gaat]. | yes/no-Q | |

| Els asked | and | if | Jan ill | is and | if | Marie on vacation goes | |||

| 'Els asked both whether Jan is ill and whether Marie is going on vacation.' | |||||||||

| c. | Els vroeg | [en | wie | er | ziek | is | en | wie | er | op vakantie | gaat]. | wh-Q | |

| Els asked | and | who | there | ill | is | and | who | there | on vacation | goes | |||

| 'Els asked both who is ill and who is going on vacation.' | |||||||||||||

Correlative en ... en ... also differs from simplex en in that it is more restricted when it comes to conjunction of extended verbal projections smaller than clauses: while example (520a) is fully acceptable, example (520b) is very much worse. The difference seems to be related to verb-second of the main verb, since comparable coordination is possible when the main verb does not have to undergo verb-second: this is illustrated in the primed examples for embedded clauses and for main clauses with complex verb constructions such as the perfect tense.

| a. | Jan | [las | het boek | en | schreef | er | een recensie | over]. | |

| Jan | read | the book | and | wrote | there | a review | about | ||

| 'Jan read the book and wrote a review of it.' | |||||||||

| b. | * | Jan | [en | las | het boek | en | schreef | er | een recensie | over]. |

| Jan | and | read | the book | and | wrote | there | a review | about |

| b'. | dat | Jan | [en | het boek | las | en | er | een recensie | over | schreef]. | |

| that | Jan | and | the book | read | and | there | a review | about | wrote | ||

| 'that Jan both read the book and wrote a review of it.' | |||||||||||

| b''. | Jan heeft | [en | het boek | gelezen | en | er | een recensie | over | geschreven]. | |

| Jan has | and | the book | read | and | there | a review | about | written | ||

| 'Jan has both read the book and written a review of it.' | ||||||||||

For completeness, the examples in (521) are added to show that the same observations can be made for constructions with monadic verbs.

| a. | De jongens | [(*en) | zingen | en | dansen]. | |

| the boys | and | sing | and | dance | ||

| 'The boys (both) sing and dance.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | de jongens | [(en) | zingen | en | dansen]. | |

| that | the boys | and | sing | and | dance | ||

| 'that the boys (both) sing and dance.' | |||||||

| c. | De jongens | hebben | [(en) | gezongen | en | gedanst]. | |

| the boys | have | and | sung | and | danced | ||

| 'The boys have (both) sung and danced.' | |||||||

The simplex and the correlative coordinators also exhibit different behavior in embedded clauses with complex verb constructions: while in (522a) simplex en can be used to conjoin main verbs, correlative en ... en ... cannot. Example (522b) shows that they do show similar behavior when they conjoin a larger verbal projection that includes the auxiliary.

| a. | dat | de jongens | hebben | [(*en) | gezongen | en | gedanst]. | |

| that | the boy | have | and | sung | and | danced | ||

| 'that the boys have both sung and danced.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | de jongens | [(en) | hebben | gezongen | en | hebben | gedanst]. | |

| that | the boy | and | have | sung | and | have | danced | ||

| 'that the boys have both sung and danced.' | |||||||||

The differences in the behavior of simplex en and correlative en ... en ... show that the simplex coordinator is able to conjoin a larger set of constituents than the correlative one; cf. Neijt (1979:§1.1). This conclusion can also be drawn on the basis of non-verbal coordination. First, the correlative coordinator is more restricted when it comes to conjunction of nominal projections smaller than DP; example (523b) shows that while simplex en is able to do this, correlative en ... en ... is not.

| a. | [(En) [DP | de mannen] | en [DP | de vrouwen]] | dansen. | DPs | |

| and | the men | and | the women | dance |

| b. | De | [(*en) [NP | oude mannen] | en [NP | jonge vrouwen]] | dansen. | NPs | |

| the | and | old men | and | young women | dance |

| c. | De | oude | [(*en) [N | mannen] | en [N | vrouwen]] | dansen. | nouns | |

| the | old | and | men | and | women | dance |

Second, the examples in (524) suggest that the same holds for adjectival phrases. Example (524a) asserts that Jan has the two independent properties of being very young and being (very) inexperienced. The sentence Jan is erg jong en onervaren, on the other hand, can be interpreted in such a way that Jan has the (single) complex property of being young and inexperienced, which Section 38.4.1, sub IA1, accounted for by assigning it the structure in (524b). The primed examples show that the correlative coordinator is only compatible with the multiple-property reading, i.e. it cannot coordinate the smaller adjectival projections without the degree adverbial; see Corver (1990:53) for more examples.

| a. | Jan is | [erg jong | en | (erg) onervaren]. | multiple-property reading | |

| Jan is | very young | and | very inexperienced |

| a'. | Jan is | [(en) | erg jong | en | (erg) onervaren]. | |

| Jan is | and | very young | and | very inexperienced |

| b. | Jan is | [erg | [jong | en | onervaren]]. | complex-property reading | |

| Jan is | very | young | and | inexperienced |

| b'. | * | Jan is | [erg | [(en) | jong | en | onervaren]]. |

| Jan is | very | and | young | and | inexperienced |

Third, as shown in (525), it appears that while both the simplex and the correlative coordinator are capable of coordinating full PPs, as in (525a), they differ in that the simplex but not the correlative coordinator can coordinate smaller projections of the preposition, as in (525b), or the nominal complement of the preposition, as in the (c)-examples.

| a. | [(en) | vlak boven het schilderij | en | vlak | onder de spiegel] | |

| and | just above the painting | and | just | below the mirror |

| b. | vlak | [(*en) | boven het schilderij | en | onder de spiegel] | |

| just | and | above the painting | and | below the mirror |

| c. | vlak | boven | [(*en) | het schilderij | en | de spiegel] | |

| just | above | and | the painting | and | the mirror |

| c'. | precies | tussen | [(*en) | het schilderij | en | de spiegel] | |

| precisely | between | and | the painting | and | the mirror |

Finally, we see in (526) that coordination of attributive modifiers by correlative en ... en ... gives rise to a marked result, while coordination by simplex en is easy; see Corver (1990:51) for more examples.

| a. | de [boeken | [(??en) | in de bibliotheek] | en | [in de leeszaal]]] | |

| the books | and | in the library | and | in the reading.room |

| b. | de | [(??en) ongeopende | en | ongelezen] | boeken] | |

| the | and unopened | and | unread | books |

Neijt concludes from data of the above kind that correlatives can only be used to link major phrases, i.e. the set of “fully expanded” projections of the lexical categories N, A, and P that function as clausal constituents, as well as to specific smaller, non-clausal verbal projections (“VPs”).

There do not seem to be any restrictions on the type of clausal constituent. As shown in (527), correlative coordinate structures with en ... en ... can be used as arguments, as complementives and (to a lesser extent) supplementives, and in various adverbial functions; there is no clear difference in this respect with the corresponding constructions with simplex en given in Section 38.4.1, sub I.

| a. | [En | de man | en | de vrouw] | zingt | een lied. | subject | |

| and | the man | and | the woman | sings | a song |

| a'. | Ik | ontmoette | [en Jan en Marie]. | direct object | |

| I | met | and Jan and Marie |

| a''. | Jan wacht | [en | op een boek | en | op een CD]. | prepositional object | |

| Jan waits | and | for a book | and | for a CD |

| b. | Jan is | [en | ziek | en | moe]. | complementive | |

| Jan is | and | ill | and | tired |

| b'. | ? | Jan ging | [en | ziek | en | moe] | naar bed. | supplementive |

| Jan went | and | ill | and | tired | to bed |

| c. | Jan werkt [en snel | en | nauwkeurig]. | manner adverbial | |

| Jan works and fast | and | accurately |

| c'. | Jan werkt | [en | morgen | en | overmorgen]. | time adverbial | |

| Jan works | and | tomorrow | and | the.day.after.tomorrow |

| c''. | Jan werkt | [en | in Amsterdam en | in Utrecht]. | place adverbial | |

| Jan works | and | in Amsterdam and | in Utrecht |

Coordinate structures with correlative en ... en ... differ semantically from those with simplex en in that they cannot be interpreted cumulatively: while example (528a) is ambiguous between a distributive and a cumulative reading, as can be seen from the fact that the modifiers beidenboth and samentogether can both be used, example (528a') has only a distributive reading. That coordinate structures with correlative en ... en ... cannot be interpreted cumulatively is also clear from the fact that such coordinate structures cannot act as antecedents for the reciprocal elkaareach other.

| a. | Jan en Marie | hebben | (beiden/samen) | de tafel | opgetild. | ambiguous | |

| Jan and Marie | have | both/together | the table | prt.-lifted | |||

| 'Jan and Marie have lifted the table.' | |||||||

| a'. | En Jan | en Marie | heeft | de tafel | opgetild. | distributive only | |

| and Jan | and Marie | has | the table | prt.-lifted | |||

| 'Both Marie and Jan have lifted the table.' | |||||||

| b. | [Jan en Marie]i | bewonderen | elkaari. | |

| Jan and Marie | admire | each.other |

| b'. | * | [En Jan en Marie]i | bewondert | elkaari. |

| and Jan and Marie | admires | each.other |

The two (a)-examples in (528) also differ in subject-verb agreement: while the coordinate structure with simplex en triggers plural agreement on the finite verb, the one with correlative en ... en ... usually triggers singular agreement. The judgments are not always sharp but Haeseryn et al. (1997:1501) claim that singular agreement is always the preferred option, which would be consistent with the hypothesis discussed in Section 38.1, sub IVD, that coordinate structures with an inherent distributive reading must trigger singular agreement on the finite verb when their coordinands are both singular; another clear example illustrating this is given in (529a). Example (529b) shows that, not surprisingly, correlative coordinate structures with en ... en ... trigger plural agreement when the two nominal coordinands are plural. Mixed cases are usually less good, although De Vries & Herringa (2008:§3) claim that there is a tendency for agreement with the coordinand closest to the verb; see also G. de Vries (1992:§2.4). Since such examples are not used in colloquial speech and native speakers tend to reject them categorically, it is difficult to evaluate this claim; we therefore simply mark the degraded examples with a percent sign.

| a. | [En | Jan en Marie] | danst3sg/*dansenpl. | |

| and | Jan and Marie | dances/dance |

| b. | [En | de jongens | en | de meisjes] | dansenpl/*danst3sg. | |

| and | the boys | and | the girls | dance/dances |

| c. | % | [En | Jan en | de meisjes] | danst3sg/dansenpl. |

| and | Jan and | the girls | dances/dance |

| c'. | % | Danst3sg/Dansenpl | [en | Jan en | de meisjes]? |

| dances/dance | and | Jan and | the girls |

Similar problems with subject-verb agreement arise with mixed person features: if the coordinands trigger the same morphological form on the finite verb, as in (530a&b), the result is generally deemed acceptable but if they trigger different forms, as in the (c)-examples, the result is severely degraded.

| a. | [En hij | en ik] | wilsg | dansen. | |

| and he | and I | want | dance | ||

| 'Both he and I want to dance.' | |||||

| b. | [En zijpl | en wij] | dansenpl | goed. | |

| and they | and we | dance(s) | well |

| c. | * | [En hij | en ik] | dans1p/danst3p | graag. |

| and he | and I | dance/dances | gladly |

| c'. | * | Dans1p/Danst3p | [en | hij | en ik] | goed? |

| dance/dances | and | he | and I | well |

Subsection I has already shown that the correlative zowel ... als ...both ... and ... differs from the correlative en ... en ...both ... and ... in that it cannot link clausal coordinands. The other instances in (531) show, however, that the two coordinators do not differ when it comes to coordinating coordinands of other categories.

| a. | * | [Zowel | Jan is ziek | als | Marie gaat op vakantie]. | CPs |

| both | Jan is ill | and | Marie goes on vacation |

| b. | [Zowel | de man | als | de vrouw] | zingt | een lied. | DPs | |

| both | the man | and | the woman | sings | a song |

| c. | Jan is | [zowel | ziek | als | moe]. | APs | |

| Jan is | both | ill | and | tired |

| d. | Jan werkt | [zowel | in Amsterdam | als | in Utrecht]. | PPs | |

| Jan waits | both | in Amsterdam | and | in Utrecht |

The examples in (531b-d) also show that correlative coordinate structures with zowel ... als ... can be used as argument, complementive or adverbial phrase; the same is shown by the fact that the substitution of zowel ... als ... for en ... en ... in the examples in (527) in Subsection A does not affect the acceptability judgments in any significant way; we leave it to the reader to construct the relevant examples.

Coordinate structures with correlative zowel ... als ... also behave like those with en ... en ... in that they are usually used as major phrases in Neijt’s sense: they are always clausal constituents or larger verbal projections. The latter is illustrated by the examples in (532) and (533), which correspond to the examples in (521) and (522) from Subsection A with correlative en ... en ....

| a. | * | De jongens | [zowel | zingen | als | dansen]. |

| the boys | both | sing | and | dance |

| b. | dat | de jongens | [zowel | zingen | als | dansen]. | |

| that | the boys | both | sing | and | dance | ||

| 'that the boys both sing and dance.' | |||||||

| c. | De jongens | hebben | [zowel | gezongen | als | gedanst]. | |

| the boys | have | both | sung | and | danced | ||

| 'The boys have both sung and danced.' | |||||||

| a. | * | dat | de jongens | hebben | [zowel | gezongen | als | gedanst]. |

| that | the boys | have | both | sung | and | danced |

| b. | dat | de jongens | [zowel | hebben | gezongen | als | hebben | gedanst]. | |

| that | the boys | both | have | sung | and | have | danced | ||

| 'that the boys have both sung and danced.' | |||||||||

The fact that non-verbal coordinate structures are usually clausal constituents is clear from the fact that the substitution of zowel ... als ... for en ... en ... in the examples in (523) to (526) from Subsection A does not materially affect the acceptability of these examples; again, we leave it to the reader to construct the relevant examples. Judgments about examples with attributive modifiers are not always sharp, however, and it is not impossible to find examples like those in (534) on the internet.

| a. | Dit | is | [een | zowel muzikaal | als sociaal | verschijnsel]. | |

| this | is | a | both musical | and social | phenomenon |

| b. | De overgang | vraagt | [een | zowel lichamelijke als emotionele | aanpassing]. | |

| the menopause | requires | a | both physical and emotional | adaptation |

Such (potential) counterexamples to the claim that correlative coordinate structures are usually clausal constituents often sound formal or artificial; the more natural way of expressing the same thoughts would be as indicated in (535). These examples involve coordination of full noun phrases with backward conjunction reduction (indicated by strikethrough); we refer the reader to Section 39.1 for relevant discussion.

| a. | Dit | is | [zowel | een muzikaal verschijnsel | als | een sociaal | verschijnsel]. | |

| this | is | both | a musical | and | a social | phenomenon |

| b. | De overgang | vraagt | [zowel | een | lichamelijke aanpassing | als | een | emotionele | aanpassing]. | |

| the menopause | requires | both | a | physical | and | an | emotional | adaptation |

Another potential counterexample with postnominal modifiers is (536), adapted from Haeseryn et al. (1997:1573). However, this coordinate structure has a parenthetical ring to it, which is also corroborated by the fact that it can be used in postverbal position; we refer the reader to Subsection IA, example (504b), for a more detailed discussion of a similar counterexample.

| a. | De boeken | zowel van Jan als van Els | zijn verkocht. | |

| the books | both of Jan and of Els | are sold | ||

| 'The books (both of Jan and of Els) are sold.' | ||||

| b. | De boeken | zijn verkocht, | zowel | van Jan | als | van Els. | |

| the books | are sold | both | of Jan | and | of Els |

We will therefore leave aside examples like (534) and (536). We note, however, that examples like those in (537) are perfectly natural, which is surprising if correlative coordinate structures are usually clausal constituents. At the present moment, we see no way to account for this.

| a. | De boeken | van | [zowel Jan als Els] | zijn verkocht. | |

| the books | of | both Jan and Els | are sold |

| b. | Jan had bezwaren | tegen | [zowel de vorm als de inhoud van het artikel]. | |

| Jan had objections | against | both the form and the content of the article |

Nominal coordinate structures with correlative zowel ... als ... are like those with en ... en ... in that they must be interpreted distributively: they cannot license adverbials such as samentogether and they cannot act as antecedents for the reciprocal elkaareach other.

| a. | [Zowel | Jan | als | Marie] | heeft | (*samen) | de tafel | opgetild. | |

| both | Jan | and | Marie | has | together | the table | prt.-lifted | ||

| 'Both Marie and Jan have lifted the table.' | |||||||||

| b. | * | [Zowel Jan als Marie]i | bewondert | elkaari. |

| both Jan and Marie | admires | each.other |

The hypothesis discussed in Section 38.1, sub IVD, that coordinate structures with an inherent distributive reading must trigger singular agreement on the finite verb when their coordinands are both singular thus correctly predicts that (539a) exhibits singular agreement. Haeseryn et al. (1997:1516) claim that in some cases a plural finite verb is preferred, but these examples seem to be artificial and intuitions seem to differ among speakers; cf. De Vries & Herringa (2008:12). De Vries & Herringa also note that some cases of plural agreement seem to be of a semantic nature, which is especially clear when at least one of the nominal coordinands is a collection noun, as in the quite natural (b)-examples in (539), which are taken from taaladvies.net/taal/advies/vraag/949.

| a. | [Zowel | Jan | als | Marie] | danst3sg/*dansenpl | graag. | |

| both | Jan | and | Marie | dances/dance | gladly | ||

| 'Both Jan and Marie like to dance.' | |||||||

| b. | [Zowel de minister | als zijn kabinet] | is/%zijn | op de hoogte. | |

| both the minister | and his cabinet | is/are | informed | ||

| 'Both the minister and his cabinet are informed.' | |||||

| b'. | [Zowel de politie | als | de brandweer] | staat/%staan | klaar. | |

| both the police | and | the fire.brigade | stands/stand | ready | ||

| 'Both the police and the fire brigade are ready.' | ||||||

There is little new to add about subject-verb agreement, since we find the familiar pattern: cases in which the two coordinands trigger the same morphological form on the finite verb are fully acceptable, while cases in which the coordinands trigger different forms are degraded to varying degrees: since judgments may vary from speaker to speaker and from case to case, we simply mark the less felicitous cases with the percent sign.

| a. | [Zowel | de jongens | als | de meisjes] | dansenpl/*danst3sg | graag. | |

| both | the boys | and | the girls | dance/dances | gladly |

| b. | [Zowel | Jan | als | de meisjes] | *danst3sg/%dansenpl | graag. | |

| both | Jan | and | the girls | dances/dance | gladly |

| c. | % | [Zowel | hij | als | ik] | danst3sg/dans1sg | graag. |

| both | he | and | I | dances/dance | gladly |

Correlative of ... of ...either ... or ... behaves more or less like en ... en ...and ... and ..., since the substitution of the former for the latter in the examples in Subsection A does not affect the acceptability in a significant way. We will illustrate this here for just a few of the cases. The examples in (541) first show that of ... of ... is able to coordinate coordinands of various categories as well as main clauses.

| a. | [Of | Jan is ziek | of | Marie gaat op vakantie]. | CPs | |

| or | Jan is ill | or | Marie goes on vacation |

| b. | [Of | de man | of | de vrouw] | zingt | een lied. | DPs | |

| or | the man | or | the woman | sings | a song |

| c. | Jan is | [of | ziek | of | moe]. | APs | |

| Jan is | or | ill | or | tired |

| d. | Jan werkt | [of | in Amsterdam | of | in Utrecht]. | PPs | |

| Jan waits | or | in Amsterdam | or | in Utrecht |

In (541a), the correlative of ... of ... precedes the initial position of the clausal coordinands and thus can be safely assumed to be external to them. This may be different in the case of the correlative ofwel ... ofwel ...either ... or .... The examples in (542) show that ofwel can not only be used external to the coordinands, but can also occupy the initial position of the coordinated clauses. This suggests that the sequence ofwel ... ofwel ... can be used both as a correlative coordinator and as a correlative adverbial. Haeseryn et al. (1997:1508), who analyze the two examples in (542) as correlative coordinate structures, claim that the order in (542a) is especially found in the Netherlands while (542b) is typically found in Belgium, but according to us both are equally acceptable in the standard variety. We represent (542b) here as an asyndetic construction, but other analyses are conceivable, such as of [wel ...] of [wel ...]; see Bredsneijder (1999:13) for discussion.

| a. | Ofwel | [ik | kom | naar jou | toe] | ofwel | [ik ga naar oma]. | |

| or | I | come | to you | prt. | or | I go to granny | ||

| 'Either I will come to you or I will go to granny.' | ||||||||

| b. | [Ofwel/*Of | kom | ik | naar jou | toe] Ø | [ofwel/*of | ga ik naar oma]. | |

| or/or | come | I | to you | prt. | or/or | go I to granny |

The examples in (541b-d) show that correlative coordinate structures with of ... of ... can be used as an argument, a complementive or an adverbial phrase. Coordinate structures with correlative of ... of ... also behave like those with en ... en ... in that they must be used as major phrases in Neijt’s sense: they are always clausal constituents or larger verbal projections. The latter is illustrated in (543) and (544), which correspond to the examples in (521) and (522) with correlative en ... en ... from Subsection A.

| a. | De jongens | [(*of) | zingen | of | dansen]. | |

| the boys | or | sing | or | dance | ||

| 'The boys sing or dance.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | de jongens | [(of) | zingen | of | dansen]. | |

| that | the boys | or | sing | or | dance | ||

| 'that the boys sing or dance.' | |||||||

| c. | De jongens | hebben | [(of) | gezongen | of | gedanst]. | |

| the boys | have | or | sung | or | danced | ||

| 'The boys have sung or danced.' | |||||||

| a. | dat | de jongens | hebben | [(*of) | gezongen | of | gedanst]. | |

| that | the boys | have | or | sung | or | danced | ||

| 'that the boys have sung or danced.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | de jongens | [(of) | hebben | gezongen | of | hebben | gedanst]. | |

| that | the boys | or | have | sung | or | have | danced | ||

| 'that the boys have sung or danced.' | |||||||||

There is little new to say about subject-verb agreement, as we find the familiar pattern: cases in which the two coordinands trigger the same morphological form on the finite verb are fully acceptable, while cases in which the coordinands trigger different forms are degraded to varying degrees. Since judgments may differ from speaker to speaker and from case to case, we mark the degraded cases with the percent sign.

| a. | [Of Jan of Marie] | werkt3sg | vandaag. | |

| or Jan or Marie | works | today | ||

| 'Or Jan or Marie is working today.' | ||||

| b. | % | [Of Jan of zijn vrienden] | werkt3sg/werken3pl | vandaag. |

| or Jan or his friends | works/work | today |

| c. | % | [Of hij | of ik] | werkt3sg/werk1sg | vandaag. |

| or he | or I | works/work | today |

The highly formal correlative hetzij ... hetzij/of ... differs from of ... of ... in that it cannot link main clauses: cf. *Hetzij ik kom naar jou hetzij ik ga naar oma. In fact, Haeseryn et al. (1997:1511) suggest that this correlative coordinator is mainly used for linking adverbial phrases: Ik kom hetzij vanmiddag, hetzij vanavondI will come either this afternoon or this evening. However, they then discuss several types of cases, suggesting that hetzij ... hetzij/of ... has roughly the same potential as of ... of ....

Subsection IA has already shown that the correlative coordinator noch ... noch ... cannot coordinate clauses. It is able, however, to coordinate smaller constituents of various categories.

| a. | * | [Noch | Jan is ziek | noch | Marie gaat op vakantie]. | CPs |

| neither | Jan is ill | nor | Marie goes on vacation |

| b. | [Noch | de man | noch | de vrouw] | zingt | een lied. | DPs | |

| neither | the man | nor | the woman | sings | a song |

| c. | Jan is | [noch | ziek | noch | moe]. | APs | |

| Jan is | neither | ill | nor | tired |

| d. | Jan werkt | [noch | in Amsterdam | noch | in Utrecht]. | PPs | |

| Jan works | neither | in Amsterdam | nor | in Utrecht |

These instances also show that correlative coordinate structures with noch ... noch ... can be used as arguments (546b), complementives (546c), and adverbials; again, replacing en ... en ... in the examples in (527) from Subsection A by noch ... noch ... has no bearing on acceptability. Correlative coordinate structures with noch ... noch ... also behave like those with en ... en ... in that they are major phrases: they are always clausal constituents or larger verbal projections. The latter is illustrated by the examples in (547)/(548), which correspond to the examples in (521)/(522) with the correlative en ... en ... from Subsection A.

| a. | De jongens | [(*noch) | zingen | noch | dansen]. | |

| the boys | neither | sing | nor | dance | ||

| 'The boys (neither) sing nor dance.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | de jongens | [(noch) | zingen | noch | dansen]. | |

| that | the boys | neither | sing | nor | dance | ||

| 'that the boys (neither) sing nor dance.' | |||||||

| c. | De jongens | hebben | [(noch) | gezongen | noch | gedanst]. | |

| the boys | have | neither | sung | nor | danced | ||

| 'The boys have (neither) sung nor danced.' | |||||||

| a. | dat | de jongens | hebben | [(*noch) | gezongen | noch | gedanst]. | |

| that | the boy | have | neither | sung | nor | danced | ||

| 'that the boys have neither sung nor danced.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | de jongens | [(noch) | hebben | gezongen | noch | hebben | gedanst]. | |

| that | the boy | neither | have | sung | nor | have | danced | ||

| 'that the boys have neither sung nor danced.' | |||||||||

With respect to subject-verb agreement, we find the by now familiar pattern: cases in which the two coordinands trigger the same morphological form on the finite verb are fully acceptable, while cases in which the coordinands trigger different forms are degraded to varying degrees. Since judgments may differ from speaker to speaker and from case to case we mark the degraded cases with the percent sign.

| a. | [Noch Jan | noch Marie] | werkt3sg | vandaag. | |

| neither Jan | nor Marie | works | today | ||

| 'Neither Jan nor Marie is working today.' | |||||

| b. | [Noch Jan | noch zijn vrienden] | *werkt3sg/%werken3pl | vandaag. | |

| neither Jan | nor his friends | works/work | today |

| c. | % | [Noch hij | noch ik] | werkt3sg/werk1sg | vandaag. |

| neither he | nor I | works/work | today |

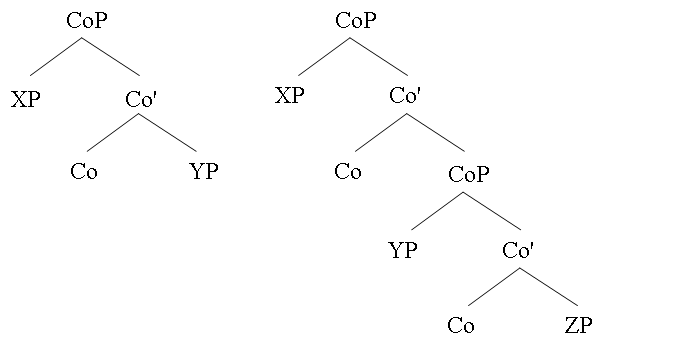

Section 38.3, sub IV, has argued that coordinators are two-place linkers, in the sense that they connect no more and no less than two coordinands. We further suggested that coordinate structures are hierarchically structured, as in the representations in Figure 31; coordinate structures with more than two coordinands are built by embedding one coordinate structure (CoP) inside another.

The claim that coordinators are two-place linkers raises several questions when we consider correlative coordinators such as zowel ... als ...both ... and ... in (550). These examples show that the number of coordinands equals the number of subparts of the correlative coordinator, suggesting that at least the initial part of the correlative coordinator cannot be analyzed as a two-place linker.

| a. | Zowel | Marie | als | Peter | (is ziek). | |

| both | Marie | and | Peter | is ill |

| b. | Zowel | Marie | als | Els | als Peter | (is ziek). | |

| both | Marie | and | Els | and Peter | is ill |

| c. | Zowel | Marie | als | Els | als Jan | als Peter | (is ziek). | |

| both | Marie | and | Els | and Jan | and Peter | is ill |

The fact that we cannot analyze all members of correlative coordinators as two-place linkers has led to a wide range of analyses of correlative coordinate structures such as (550). We will briefly review some of the proposals in the following subsections: these subsections are thus more theoretical in nature but they also discuss some important empirical issues.

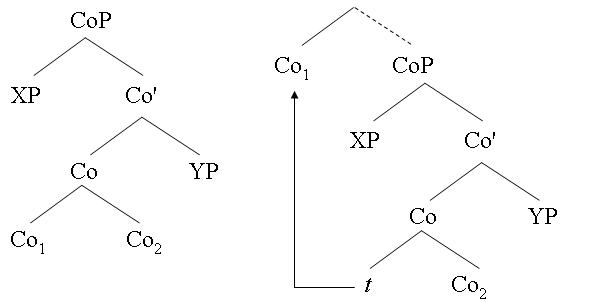

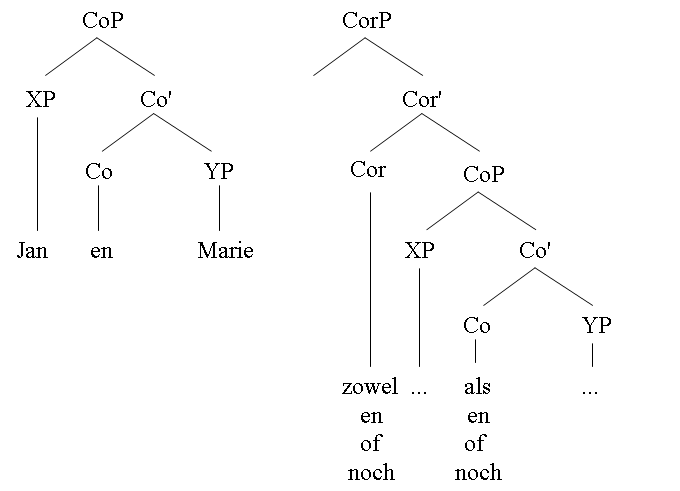

A promising solution to the problem that the initial parts of a correlative coordinator cannot be analyzed as two-place linkers would be to assume that the two subparts Co1 (= the initial part) and Co2 constitute subparts of a single (complex) head; cf. Larson (1985). The base structure of correlative coordinate structures would then be as in the left-hand side of Figure 32, while the surface structure is derived by moving the initial part to some position higher in the structure; the dotted line indicates an indeterminate number of nodes external to the coordinate structure CoP.

Larson’s main argument in favor of the analysis in Figure 32 is semantic in nature in that the presumed landing site of Co1 restricts the semantic scope of Co2, which was argued mainly on the basis of an observation about English either ... or ... We will not review the semantic arguments in the following, but instead focus on a number of syntactic arguments for and against this analysis.

Dutch seems to provide some evidence in favor of Larson’s proposal, in that the two parts of zowel ... als ... can occur side by side between the two coordinands, as in (551a): cf. Haeseryn et al. (1997:1514). This would follow from the complex-head hypothesis if we were to assume that movement of the initial part of zowel ... als ... is not obligatory: (551a) would then reflect the underlying order of correlative coordinate structures with this correlative coordinator. Note, however, that (551a) is less common than the split pattern in (550a), and that the possibility of the two parts being adjacent is excluded for other correlative coordinators; cf. Van der Heijden (1999:83). We illustrate the impossibility of adjacency with the highly formal correlative hetzij ... of ... in (551b), because one might want to argue that the unacceptability of examples such as (551c) is due to the fact that the two members of the correlative coordinator have the same form; movement of of may therefore be preferred in order to avoid haplology.

| a. | Marie zowel | als Jan | (is ziek). | |

| Marie both | as Jan | is ill |

| b. | * | Marie hetzij of Jan (is ziek). |

| Marie either or Jan is ill |

| c. | * | Marie of of Jan (is ziek). |

| Marie or or Jan is ill |

Because the acceptability of (551a) may simply be a quirk of the formal register, i.e. a relic of the older adverbial use of zowel als as described in the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (item Zoowel, sub 1), it is not clear whether we can use it as an argument in favor of the complex-head hypothesis.

The evidence from English that Larson presents in support of this hypothesis does not straightforwardly carry over to Dutch; we will illustrate this by comparing the crucial English data, which is not taken from Larson’s paper but from Schwarz (1999), with similar Dutch cases. Example (552a) provides the standard case in which the initial part of the correlative either ... or ... precedes the first coordinand of the coordinate structure. This structure should be derived by moving either from its base position to a position immediately preceding the coordinate structure (e.g. by adjunction of either to CoP). This analysis can also be applied to the corresponding Dutch case in (552b).

| a. | that John ate [eitheri [CoP rice [Co' [Co ti or] beans]]]. |

| b. | dat | Jan | [ofi [CoP | rijst [Co' [Co ti | of] | bonen]]] | at. | |

| that | Jan | either | rice | or | beans | ate |

Larson has shown that either can also precede the main verb: that John either ate rice or beans. On the more traditional assumption that either occupies its base position and indicates the left edge of the coordinate structure, we could consider the two analytic options in (553). Representation (553a) should be rejected, however, because it violates the co-occurrence restriction on coordinands discussed in Section 38.3, sub I, that the coordinands must be syntactically similar. Representation (553b) with ellipsis in the second coordinand is suspect, as Section 39.1 will show that there are reasons not to accept forward conjunction reduction.

| a. | that John either [[VP ate rice] or [DP beans]]. |

| b. | that John either [[VP ate rice] or [VP ate beans]]. |

The complex-head hypothesis elegantly avoids such problems if we assume that either can be moved to a position immediately before VP, as in (554a). The problem with extending this analysis to Dutch is that this movement leads to the same order as adjunction to CoP; we can only show that of has moved to a position external of VP if it would have crossed some other constituent but we have not been able to construct convincing examples of this kind; for instance, example (554c), in which of has crossed an indirect object, is not very good.

| a. | that John [eitheri [VP ate [CoP rice [Co' [Co ti or] beans]]]]. |

| b. | dat | Jan | [ofi [VP [CoP | rijst [Co' [Co ti | of] | bonen]]] | at]]. | |

| that | Jan | either | rice | or | beans | ate |

| c. | * | dat | Jan | [ofi [VP | de hond [CoP | rijst [Co' [Co ti | of] | bonen]]] | te eten | gaf]]. |

| that | Jan | either | the dog | rice | or | beans | to eat | gave | ||

| Intended reading: 'that Jan either fed the dog rice or beans.' | ||||||||||

English either can also precede the subject of the clause: that either John ate rice or beans. Assuming that either occupies its base position and indicates the left edge of the coordinate structure, we again have the two analytic options in (555), but these should be rejected for the same reasons as those in (553): representation (555a) should be rejected because it violates the co-occurrence restriction on coordinands, and example (555b) is suspect because there are reasons not to accept forward conjunction reduction.

| a. | that either [[TP John ate rice] or [DP beans]]. |

| b. | that either [[VP John ate rice] or [VP John ate beans]]. |

The complex-head hypothesis can account for the acceptability of that either John ate rice or beans by assuming that either can be moved to a position immediately preceding TP, as in (556a), but this analysis cannot be extended to Dutch because the resulting representation in (556b) is unacceptable: the first occurrence of of cannot precede the subject in Dutch.

| a. | that [eitheri [TP John ate [CoP rice [Co' [Co ti or] beans]]]]. |

| b. | * | dat | [ofi [TP | Jan [CoP | rijst [Co' [Co ti | of] | bonen] | at]]]. |

| that | either | Jan | rice | or | beans | ate |

Although the complex-head analysis provides an elegant solution for a number of interesting descriptive problems in English, the unacceptability of the examples in (554c) and (556b) shows that it overgenerates when it comes to Dutch.

Schwarz (1999) argues against the complex-head analysis of correlative coordinators on the basis of particle-verb constructions like those in (557); the diacritics are those given by Schwarz, who notes that all of his informants judge the primed examples to be degraded (ranging from marginal to unacceptable).

| a. | She turned either the test or the homework in. |

| a'. | ?? | Either she turned the test or the homework in. |

| b. | They locked either you or me up. |

| b'. | ?? | Either they locked you or me up. |

Schwarz further notes that the instances in (558a&b) below are marked when the coordinate structure is followed by an adverbial phrase, as in the corresponding primed examples. Schwarz (1999:349) concludes from this that the coordinate structure must be clause-final in order for either to occur detached from it; otherwise either usually immediately precedes the coordinate structure.

| a. | Either he invited you or me. |

| a'. | ? | Either he invited you or me (to a party). |

| b. | Either this pleased Bill or Sue. |

| b'. | ? | Either this pleased Bill or Sue (a lot). |

Interestingly, the same can be observed in Dutch: the examples in (559) show that (apparently) displaced of is possible in main clauses with a finite main verb in second position but not with a non-finite main verb in final position.

| a. | Of | Jan at | rijst | of bonen. | |

| either | Jan ate | rice | or beans | ||

| 'Either Jan ate rice or beans.' | |||||

| b. | * | Of | Jan heeft | rijst of bonen | gegeten. |

| either | Jan has | rice or beans | eaten | ||

| 'Either Jan has eaten rice or beans.' | |||||

Schwarz also observes that the English primed examples in (557) become fully grammatical when the (apparently) stranded or-XP phrase is placed after the particle, as in (560). From this he concludes that cases in which either is seemingly displaced are in fact (covert) split coordination constructions (with a reduced second coordinand; see below).

| a. | [[Either she turned the test in] or [the homework]]. |

| b. | [[Either they locked me up] or [you]]. |

That we are dealing with a kind of “split” coordination is confirmed by the fact, illustrated in (561), that the unacceptable Dutch example in (559b) also becomes fully acceptable when the of-XP phrase is placed after the participle gegeteneaten.

| Of | Jan heeft | rijst | gegeten, | of bonen. | ||

| either | Jan has | rice | eaten | or beans | ||

| 'Either Jan has eaten rice, or beans.' | ||||||

Finally, Schwarz argues that split coordination constructions such as (560) involve clausal coordinands, with reduction of the second clause. This would be entirely consistent with the independently motivated conclusion from Section 38.3, sub IIB, that the split coordination construction in (562b) cannot be derived from the same underlying source as (562a) because this would leave the difference in subject-verb agreement unexplained; we concluded from this that the phrase following en is in all likelihood a reduced verbal projection.

| a. | dat | [Marie en Jan] | morgen | op visite | komen/*komt. | |

| that | Marie and Jan | tomorrow | on visit | come/comes | ||

| 'that Marie and Jan will visit us tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Marie morgen | op visite | komt/*komen, | en Jan. | |

| that | Marie tomorrow | on visit | comes/come | and Jan |

Schwarz’ alternative analysis makes the complex-head hypothesis, as well as the concomitant movement of the initial part of the correlative coordinator in Figure 32 unnecessary. By denying that the initial part of the correlative Co1 can be moved, the apparent problem that the Dutch examples in (554c) and (556b) are unacceptable also disappears. For these reasons, we do not adopt the complex-head hypothesis.

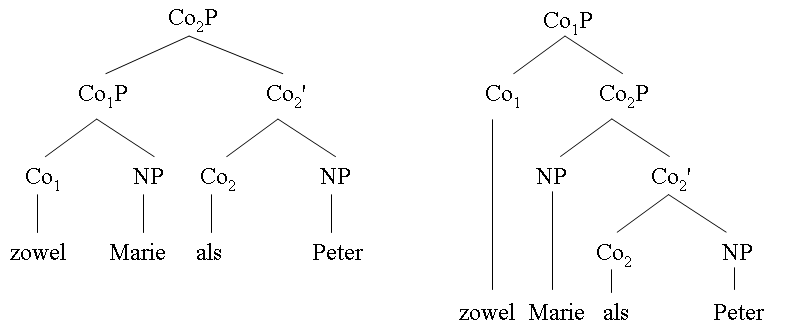

A second line of investigation starts from the assumption that the constituting parts of correlative coordinators are all heads. On this assumption, there seem to be two obvious ways of representing correlative coordinate structures: either the initial part of this structure takes the first coordinand as its complement, as in the left-hand representation in Figure 33, or it takes the full coordinate structure as its complement, as in the right-hand representation: see Kayne (1994:58) including footnote 2.

Both representations in Figure 33 are problematic in that the initial part of the correlative coordinator does not behave as a two-place linker: it takes only a single complement, viz. the noun phrase Marie in the left-hand structure and the coordinate structure Co2P in the right-hand structure. The left-hand representation also violates the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands, according to which the coordinands must be syntactically similar, because als links the CoP zowel Marie and the noun phrase Peter. In the right-hand representation, zowel does not enter into a relation with either coordinand. The two double-head analyses are therefore not very promising in their present form, but there are slightly more sophisticated versions of them that may be more promising.

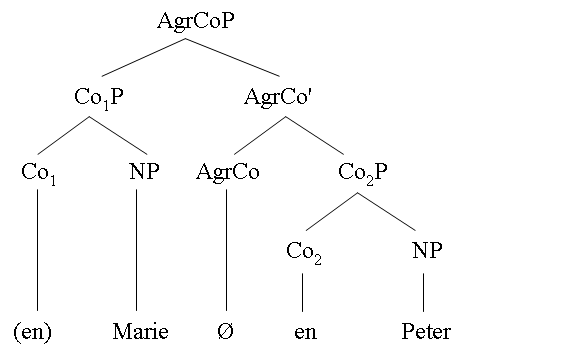

The two double-head hypotheses in Figure 33 entail that at least the initial part of the correlative coordinator cannot be analyzed as a two-place linker. If so, there is no well defined reason for assuming that the second member should be a two-place linker. Indeed, this presupposition is rejected by Van der Heijden (1999), who argues that the two parts of correlative coordinators are similar in that they take only a complement. However, this requires the assumption of a separate head, which Van der Heijden calls AgrCo, which links the two CoPs. We illustrate this here for the correlative en … en …and … and ….

The parentheses around en, the initial part of the coordinate structure in Figure 34, are used to indicate that Van der Heijden claims that simplex and correlative coordinators have essentially the same structure: the only difference is whether the initial part is phonetically realized. The functional head AgrCo is assumed to perform several functions. First, it ensures agreement between Co1P and Co2P, which is said to block unacceptable formations such as en ... of ... in (563a). Second, it plays a role in the agreement relation with elements external to the coordinate structure by ensuring that the coordinate structure in (563b) triggers plural agreement on the finite verb despite the fact that the coordinands are singular. Third, the structure can be used to account for split coordination: Co1P and Co2P are maximal projections and can therefore be separated by movement, as illustrated by (563c).

| a. | * | [En Marie of Peter] | danst/dansen. |

| and Marie or Peter | dances/dance |

| b. | [Marie | en | Peter] | dansenpl/*danstsg. | |

| Marie | and | Peter | dance/dances |

| c. | Ik | heb | (en) Marie | gezien | en Peter. | |

| I | have | and Marie | seen | and Peter |

Unfortunately, the proposal is not sufficiently developed to be fully evaluated. Moreover, the arguments based on (563b&c) seem flawed. First, because simplex and correlative coordinators are claimed to make use of the same structure in Figure 34, there is no a priori reason to expect the difference in subject-verb agreement properties found between (563b) and (564a); although Van der Heijden acknowledges this difference, she does not provide an account of it. Second, on the assumption that the Co2P in Figure 34 can be moved to the right in order to derive (563c), we would wrongly expect the coordinate structure constraint violation in example (564b) to be acceptable as well. Third, Section 38.3, sub IIB, has provided arguments to the effect that split coordination constructions such as (563c) cannot be derived from the same source as their non-split counterparts.

| a. | [En | Marie | en | Peter] | danstsg/*dansenpl. | |

| and | Marie | and | Peter | dances/dance |

| b. | * | [En Peter]i | heb | ik | [(en) Marie ti] | gezien. |

| and Marie | have | I | and Peter | seen |

The discussion above has shown that there are reasons not to adopt the AgrCoP-version of the double head analysis in Figure 34 at this stage of development.

The second version of the double-head analysis of correlative coordinators maintains the claim that coordinators are two-place linkers by dropping the assumption that the initial part is coordinator-like. Van Zonneveld (1992) proposes that the initial part is a special type of functional head, which he refers to as Cor, which takes a regular coordinate structure (CoP) as its complement. On this assumption, the representation of correlative coordinate structures is as given in the right-hand representation in Figure 35.

Zonneveld motivates the CorP projection by referring to the fact, discussed in Subsection II, that coordinands of correlative coordinate structures are always major phrases. For instance, the examples in (565) show that while simplex en can link DPs, NPs and nominal heads, the correlative head en can only precede coordinated DPs. This can be made to follow by stipulating that the correlative head Cor can only select CoPs that function as major phrases.