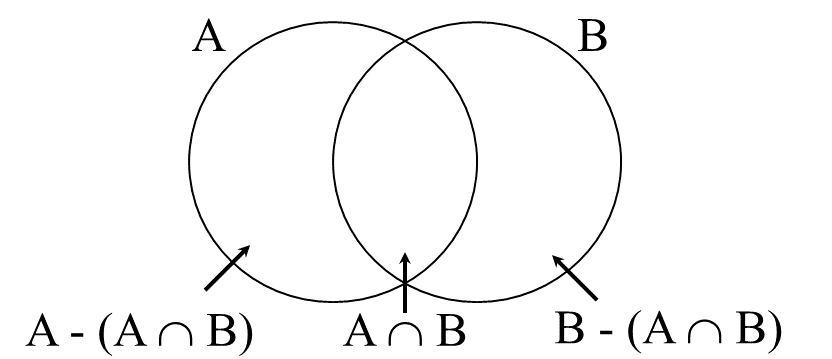

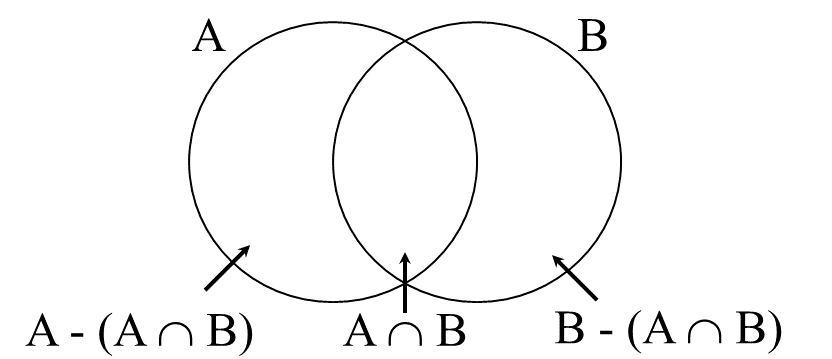

The easiest way to explain the core meaning of the articles is to use Figure 1 from Section 15.1.2, sub IIA, repeated below, which can be used to represent the subject-predicate relation in a clause. In this figure, A represents the denotation set of the lexical part (i.e. the NP-part) of the subject, and B represents the set denoted by the verb phrase. The intersection A ∩ B denotes the set of entities for which the proposition expressed by the clause is claimed to be true.

Figure

1: Set-theoretic representation of the subject-predicate relation

For the sake of illustration, suppose for a moment that a proper noun denotes a singleton set (which is actually different from what is usually assumed in current formal semantics; cf. Smessaert 2014). An example such as Jan wandelt op straat then expresses that the set denoted by A, viz. {Jan}, is properly included in set B, which consists of people walking in the street. In other words, it expresses that A - (A ∩ B) is empty.

The core function of the determiners is to specify the intersection (A ∩ B) and the remainder of set A, i.e. A - (A ∩ B). The definite article dethe in (7) expresses that in the domain of discourse (domain D) all entities that satisfy the description of the NP-part (i.e. jongen) of the subject are contained in the intersection A ∩ B, i.e. that A - (A ∩ B) is empty. The singular noun phrase de jongenthe boy in (7a) therefore has approximately the same interpretation as the proper noun Jan in the discussion above; it expresses that the cardinality of A ∩ B is 1 (for which we will use the notation: |A ∩ B| = 1). The only difference between the singular and plural examples in (7) is that the latter expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

7

| a. | | De jongen | loopt | op straat. |

| | | the boy | walks | in the.street |

| a'. | | de/het NPsg: |A ∩ B| = 1 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| = 0 |

| b. | | De jongens | lopen | op straat. |

| | | the boys | walk | in the.street |

| b'. | | de NPpl: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| = 0 |

The semantic contribution of the indefinite articles in (8a&b) is to indicate that A ∩ B is not empty; they imply nothing about the set A - (A ∩ B), which may or may not be empty. The difference between the singular indefinite article een and the (phonetically empty) plural indefinite article ∅ is that the former expresses that |A ∩ B| = 1, whereas the latter expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

8

| a. | | Er | loopt | een jongen | op straat. |

| | | there | walks | a boy | in the.street |

| | | 'There is a boy walking in the street.' |

| a'. | | een NPsg: |A ∩ B| = 1 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| ≥ 0 |

| b. | | Er | lopen ∅ | jongens | op straat. |

| | | there | walk | boys | in the.street |

| | | 'There are boys walking in the street.' |

| b'. | | ∅ NPpl: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| ≥ 0 |

It is important to note that only parts of the meaning descriptions in the primed examples of (7) and (8) are inherently linked to the determiner: definite articles imply that A - (A ∩ B) is empty, whereas indefinite articles do not. The claims with respect to the cardinality of the intersection A ∩ B do not come from the articles but from the number marking (i.e. singular versus plural) on the nouns: the singular marking expresses that |A ∩ B| = 1, whereas the plural marking expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

The fact that the cardinality of the set denoted by the full noun phrase is not determined by the article, but by the number marking on the head noun, makes it understandable why articles can also occur with non-count nouns like wijnwine. The difference between definite and indefinite noun phrases headed by a non-count noun is simply that the former refers to a contextually determined amount of wine, e.g. a bottle of wine in the kitchen in the case of (9a), whereas the latter refers to an indeterminate amount of wine not previously mentioned in the discourse, as in the case of (9b).

9

| a. | | Pak | jij | de wijn | even? |

| | | Fetch | you | the wine | prt. |

| | | 'Please, can you fetch the wine.' |

| b. | | Jan heeft ∅ | wijn | gekocht. |

| | | Jan has | wine | bought |

| | | 'Jan has bought wine.' |

The meaning we ascribe to the number marking, which we owe to Farkas & De Swart (2008), may come as a surprise. First, the meaning attributed to the singular indefinite noun phrase in (8a) breaks with the tradition in predicate calculus, which translates the indefinite article by means of the existential operator ∃x and thus implies that the article expresses that the intersection A ∩ B contains at least one member, i.e. |A ∩ B| ≥ 1. Second, (8b) attributes this meaning instead to the plural marking, which seems to contradict the fact that plural nouns are normally interpreted as expressing that the intersection A ∩ B contains more than one member, i.e. |A ∩ B| > 1. In the following, we will therefore motivate why we adopt the proposal of Farkas & De Swart (who actually assume that the plural marking is ambiguous and can express either |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 or |A ∩ B| > 1, but we will ignore this here).

The traditional assumption that indefinite singular noun phrases express that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 predicts that a speaker will use an indefinite singular noun phrase when he has no idea about the cardinality of a particular non-empty set. The proposal here that the plural marking on the noun expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1, on the other hand, predicts that the speaker will use an indefinite plural noun phrase in this case. That the latter prediction is correct becomes clear when we consider the questions in (10): if a speaker is interested in whether the addressee is a parent, i.e. whether the addressee has one or more children, the typical way of asking the question would be as in (10a), not as in (10b).

10

| a. | | Heb | je | kinderen? |

| | | have | you | children |

| | | 'Do you have children?' |

| b. | # | Heb | je | een kind? |

| | | have | you | a child |

| | | 'Do you have a child?' |

Of course, example (10b) is not ungrammatical, but it can only be used if the speaker presupposes that the cardinality of the referent set will not be greater than one (e.g. in a country with a one-child policy): so one could ask a question like Heb je al een kind?Do you already have a child? if the addressee is assumed to be childless under normal circumstances. For the same reason, examples such as (11a) require the use of the singular, since this expresses that the speaker is aware of the fact that people normally have only one nose; using the plural would violate Grice’s (1975) maxim of quantity, since it would falsely suggest that the speaker lacks this knowledge. Similarly, by opting for one of the options in (11b), the speaker can make more explicit what he actually wants, a single cigarette or a pack of cigarettes.

11

| a. | | Heb | jij | een mooie neus/#mooie neuzen? |

| | | have | you | a beautiful nose/beautiful noses |

| | | 'Do you have a beautiful nose/beautiful noses?' |

| b. | | Heb | je | een sigaret/sigaretten | voor me? |

| | | have | you | a cigarette/cigarettes | for me |

| | | 'Do you have a cigarette/cigarettes for me?' |

Another context that licenses the use of a plural indefinite noun phrase concerns clauses containing the modal willento want. Consider the two examples in (12): example (12a) is similar to (10a) in that it inquires whether the addressee intends to have one or more cats as pets; example (12a) would be infelicitous in this use, suggesting instead that the speaker has in mind a particular cat that is on offer.

12

| a. | | Wil | je | katten? |

| | | want | you | cats |

| | | 'Do you want cats?' |

| b. | # | Wil | je | een kat? |

| | | want | you | a cat |

| | | 'Do you want a cat?' |

A third case in which the speaker may use a plural indefinite noun phrase to express that he has no presupposition about cardinality is in the case of inferences. If the speaker is visiting some people he does not know intimately and enters a room littered with toys, he might say something like (13a) without ruling out the possibility that his hosts have only one child. For at least some speakers, the use of example (13b) in this context is less felicitous, since it may suggest that the speaker has reason to believe that the cardinality of the set of children is one.

13

| a. | | Er | wonen | hier | kinderen. |

| | | there | live | here | children |

| | | 'There are children living here.' |

| b. | # | Er | woont | hier | een kind. |

| | | there | lives | here | a child |

| | | 'There is a child living here.' |

That the singular number marking in definite noun phrases such as de jongenthe boy in (7a) implies that the intersection has cardinality 1 seems uncontroversial, which means that Farkas & De Swart’s proposal makes it possible to assign a single meaning to the singular: |A ∩ B| = 1. That the plural marking in definite phrases like (7b) can express |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 is harder to establish. This is due to the fact, discussed in Section 19.1.1.2 below, that the definite article generally presupposes that the speaker and the addressee are able to identify the referents in the referent set of the noun phrase. In the majority of cases, therefore, the speaker will know whether the cardinality of the referent set is one or more than one. If the former is the case, using a singular definite noun phrase will be more informative than using a plural definite noun phrase; the former will therefore be preferred by Grice’s maxim of quantity.

Nevertheless, there are certain contexts that show that plural definite noun phrases do not make any implication about the cardinality of the referent set. Consider an employee of a company who is responsible for handling customers’ complaints. When he comes into the office in the morning, the first thing he does is look at the new complaints, if there are any. One morning there is no mail on his desk; he picks up the phone and asks the person who normally sorts and distributes the mail the question in (14a), which somehow presupposes that there will be some new complaints, but does not imply anything about the number of those complaints. In this respect, (14a) is crucially different from (14b), which implies that the referent set has cardinality 1.

14

| a. | | Kan | je | me | de nieuwe klachten | brengen? |

| | | can | you | me | the new complaints | bring |

| | | 'Can you bring me the new complaints?' |

| b. | | Kan | je | me | de nieuwe klacht | brengen? |

| | | can | you | me | the new complaints | bring |

| | | 'Can you bring me the new complaint?' |

The same can be observed with conditionals. Example (15a) is taken from a text on family law concerning divorce. The use of the singular noun, as in (15b), would be decidedly odd in this context, since it would imply that in all cases of divorce there is only one child involved; such implications are completely absent in examples such as (15a). The examples in (14) and (15) again support Farkas & De Swart’s proposal that the plural has a single meaning: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

15

| a. | | Als | de kinderen | aan één van de ouders | zijn toegewezen, | dan ... |

| | | if | the children | to one of the parents | are prt.-awarded | then |

| | | 'If one of the parents is awarded the custody of the children ...' |

| b. | # | Als | het kind | aan één van de ouders | is toegewezen, | dan ... |

| | | if | the child | to one of the parents | is prt.-awarded | then |

The semantic function of the negative article/quantifier geenno is to indicate that the intersection of A and B is empty: |A ∩ B| = 0. No claims are made about either set A or set B: it may or may not be the case that domain D contains a set of boys and/or that there is a set of people who are walking in the street.

16

| a. | | Er | loopt | geen jongen | op straat. |

| | | there | walks | no boy | in the.street |

| a'. | | geen NPsg: |A ∩ B| = 0 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| ≥ 0 |

| b. | | Er | lopen | geen jongens | op straat. |

| | | there | walk | no boys | in the.street |

| b'. | | geen NPpl: |A ∩ B| = 0 & |A ‑ (A ∩ B)| ≥ 0 |

The distinction between singular and plural is again not related to the meaning of the article: examples like (16a&b) can be used to deny a presupposition that |A ∩ B| = 1 or |A ∩ B| ≥ 1, respectively. If there is no such presupposition, the plural is used. Consider the situation where Jan is in hospital with a broken leg. He is bored stiff, so his friend Peter always brings him something to read when he visits: the number of books varies according to their size. One day, Peter comes to the hospital empty-handed. In this case, Jan would probably ask the question in (17a) rather than the one in (17b), since the latter assumes that Peter usually brings only one book.

17

| a. | | Heb | je | geen boeken | voor me | meegenomen? |

| | | did | you | no books | for me | prt-.taken |

| | | 'Didnʼt you bring me any books?' |

| b. | # | Heb | je | geen boek | voor me | meegenomen? |

| | | did | you | no book | for me | prt-.taken |

The meaning contributions of the three articles can be summarized by Table (18). There are no implications concerning the cardinality of the intersection A ∩ B, since it is the role of the number marking of the noun to specify this: the singular marking expresses that |A ∩ B| = 1 and the plural marking that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

18 The core meaning of the articles

| A ∩ B | A - (A ∩ B) |

| definite article de/het | non-empty | empty |

| indefinite article een/∅ | non-empty | indeterminate |

| negative article geen | empty | indeterminate |

In the following sections, however, we will see that more can be said about the precise characterization of the meaning of the articles, and it will also become clear that some uses of the articles do not fall within the general characterization of the meaning of the articles given in this section.