- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This section discusses degree quantifiers like veelmany/much and weinigfew/little. Subsection I deals with their use as prenominal modifiers of noun phrases. Subsection II deals with their independent use as arguments; degree quantifiers cannot be used as floating quantifiers. Degree quantifiers are also sometimes used as adverbial phrases, but we defer discussion of this use to Section 20.2.6.

This subsection discusses the use of gradable quantifiers as modifiers of noun phrases. We begin with a discussion of the degree quantifiers veelmany/much and weinigfew/little, which indicate that the cardinality/quantity in question is respectively higher or lower than some tacitly assumed norm. We then discuss the degree quantifiers voldoendesufficient, genoegenough and zatplenty, which indicate that some tacitly assumed norm is met.

This subsection discusses a number of semantic, morphological, and syntactic properties of the degree quantifiers veelmany/much and weinigfew/little. Some examples are given in (256).

| a. | Er | lopen | weinig jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | few boys | in the.street | ||

| 'There are few boys walking in the street.' | |||||

| b. | Er | lopen | veel jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | many boys | in the.street | ||

| 'There are many boys walking in the street.' | |||||

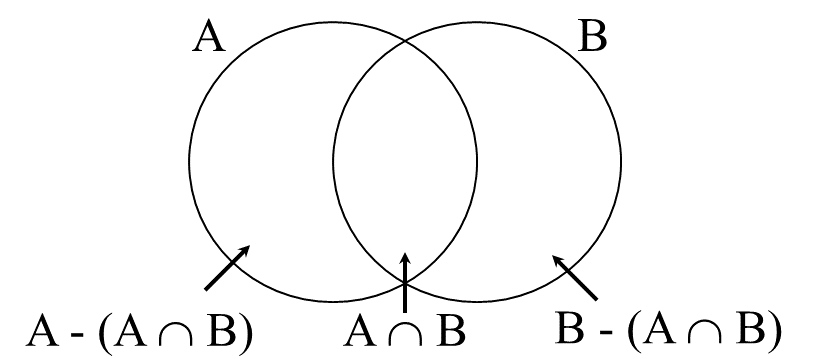

The quantifiers veelmany and weinigfew in (256) are not only existential, but in addition express that the cardinality of the boys walking in the street is higher/lower than some contextually determined norm. In terms of Figure 1, repeated below, this means that they express that the intersection of the set of boys (set A) and the set of entities walking in the street (set B) is non-empty: A ∩ B ≠ ∅.

The contextually determined norm is not an absolute number, but has a certain range; in the semantic representations in (257), n and n' refer to the lower and upper bounds of this range, respectively.

| a. | Er | lopen | weinig jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | few boys | in the.street |

| a'. | ∃x (x:boy) (x walk in the street & 1 < |A ∩ B| < n) |

| b. | Er | lopen | veel jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | many boys | in the.street |

| b'. | ∃x (x:boy) (x walk in the street & |A ∩ B| > n') |

Degree quantifiers differ from purely existential quantifiers in that they modify not only plural count nouns but also non-count nouns, such as the substance noun water in (258). In this case, of course, the notion of cardinality is not applicable; instead, the degree quantifier expresses that the quantity of the substance denoted by the noun is greater/smaller than some contextually determined norm.

| a. | Er | zit | veel water | in de fles. | |

| there | is | much water | in the bottle |

| b. | Er | zit | weinig water | in de fles. | |

| there | is | little water | in the bottle |

The quantified noun phrases in (257) and (258) function as the subject of an expletive er construction and are therefore clearly weak. However, the examples in (259) show that it is also possible to use degree quantifiers in strong noun phrases.

| a. | Veel boeken | bevatten | honderden zetfouten. | |

| many books | contain | hundreds [of] misprints |

| b. | Weinig boeken | bevatten | geen zetfouten. | |

| few books | contain | no misprints |

Like the existential quantifier enkele, the degree modifiers veel and weinig can either quantify over a pre-established set of entities in domain D or express a more “generic” meaning, i.e. quantify over all relevant entities in the speaker’s conception of the universe. In the first reading, an example such as (259a) asserts that, out of a contextually determined set of books, the number of books containing misprints is higher than some tacitly assumed norm. In the second (“generic”) reading, the speaker claims that a relatively large proportion of all existing books contain misprints. Example (259b) exhibits the same kind of ambiguity.

The degree quantifiers veel and weinig are adjectival in nature: they can themselves be modified by degree modifiers like ergvery or tetoo and can be used as input for comparative and superlative formation, although the superlative form (het) minste gives rise to a marked result.

| veel | weinig | |

| degree modification | erg/te veel boeken ‘very/too many books’ | erg/te weinig boeken ‘very/too few books’ |

| comparative formation | meer boeken ‘more books’ | minder boeken ‘fewer books’ |

| superlative formation | de meeste boeken ‘most books’ | ??de minste boeken ‘fewest books’ |

Given its adjectival properties, it is not surprising that quantificational veel can be found in the same position as attributive adjectives, i.e. in a position between the article dethe and the noun. The primeless examples in (261) further show that veel must be inflected with the attributive –e ending when the article is present, but that the inflection is optional when there is no phonetically realized article. The primed examples show that although inflected weinig is possible when the article is present, it leads to a degraded result without an overt article.

| a. | de | vele/*veel | boeken | |

| the | many/many | books |

| a'. | de | weinige/*weinig | boeken | |

| the | few/few | books |

| b. | veel/vele | boeken | |

| many/many | books |

| b'. | weinig/*weinige | boeken | |

| few/few | books |

The alternation found in (261b) suggests that we are dealing with a structurally ambiguous example. A plausible analysis of this case would be that the presence of the attributive –e ending signals that the quantifier veel functions as an adjectival modifier of the head noun boeken, while its absence signals that we are dealing with a quantifier located in the specifier position of NumP. The representation in (262a) is comparable to attributive constructions such as (de) mooie boekenthe beautiful books; the representation in (262b) is comparable to run-of-the-mill quantificational constructions such as (*de) sommige/alle boekensome/all books; cf. Section 20.2.1, sub V, for a discussion of the silent noun number.

| a. | [DP | de/Ø [NP | vele boeken]] | |

| [DP | the/Ø | many books |

| b. | [DP | Ø/*de [NumP | [veel number] [Num [NP | boeken]]]] | |

| [DP | Ø/the | many | books |

The judgments on the primed examples in (261) suggest that weinig cannot easily be used as an attributive modifier of the head noun, as in (263a), and strongly favors a quantificational use, as in (263b).

| a. | [DP | de/*Ø [NP | weinige boeken]] | |

| [DP | the/Ø | few books |

| b. | [DP | Ø/*de [NumP | [weinig number] [Num [NP | boeken]]]] | |

| [DP | Ø/the | few | books |

There are a number of potential problems with the proposed analysis. The first concerns N-ellipsis. Example (264a) shows that N-ellipsis is normally possible in the context of an attributive adjective, provided that the context provides sufficient information to identify the content of the empty noun; cf. Section A28.4. It is therefore surprising that N-ellipsis is excluded with the inflected quantifier vele in (264b). Although the reason for the unacceptability of (264b) is not clear, it should be noted that its superlative counterpart in (264c) is perfectly acceptable; this can be taken as support for the proposed analysis.-

| a. | Hij | heeft [DP | de blauwe e] | verkocht. | |

| he | has | the blue | sold | ||

| 'He has sold the blue one(s).' | |||||

| b. | * | Hij | heeft [DP | de vele e] | verkocht. |

| he | has | the many | sold |

| c. | Hij | heeft [DP | de meeste e] | verkocht. | |

| he | has | the most | sold | ||

| 'He has sold most of them.' | |||||

A second potential problem concerns the quantitative er construction discussed in Section 20.3. This construction can arise with indefinite noun phrases when the nominal gap e follows a cardinal numeral or a quantifier, but produces an unacceptable result when the gap follows an attributive modifier of the empty noun; cf. (265).

| a. | Zij | heeft | er [DP Ø [NumP | vier/enkele [Num [NP e]]]] | gekocht. | |

| she | has | er | four/some | bought | ||

| 'She has bought four/some of them.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Zij | heeft | er [DP Ø [NP | mooie e]] | gekocht. |

| she | has | er | beautiful | bought |

The analysis in (262) would therefore predict that quantitative er can only occur with bare veel, but this is not fully borne out; the examples in (265) show that the bare and inflected forms are both possible, although the inflected form seems somewhat outdated, as evidenced by the fact that it appears less frequently on the internet and mainly in formal texts.

| a. | Zij | heeft | er [DP Ø [NumP | veel [Num [NP e]]]] | gekocht. | |

| she | has | er | many | bought | ||

| 'She has bought four/some of them.' | ||||||

| b. | $ | Zij heeft | er [DP Ø [NP | vele e]] | gekocht. |

| she has | er | many | bought |

We leave these potentially problematic issues for future research, but we think that the analysis in (262) deserves serious consideration.

The degree quantifiers voldoendesufficient, genoegenough and zatplenty express that the cardinality of the intersection A ∩ B in Figure 1 satisfies a contextually determined norm. Again, this norm is not an absolute number, but has a certain range: n and n' in (267b) refer to the lower and upper bound of this range, respectively.

| a. | Er | lopen | voldoende jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | enough boys | in the.street | ||

| 'There are enough boys walking in the street.' | |||||

| b. | ∃x (x:boy) (x walk in the street & n ≤ |A ∩ B| ≤ n') |

Example (268) shows that degree modifiers of this type are similar to veelmany/much and weinigfew/little in that they can also modify non-count nouns.

| Er | zit | voldoende water | in de fles. | ||

| there | is | enough water | in the bottle | ||

| 'There is enough water in the bottle.' | |||||

Degree quantifiers like genoeg and zat are somewhat freer in their syntactic distribution than the other degree quantifiers; the primeless examples in (269) show that these quantifiers need not be placed in prenominal position, but can also occur postnominally. This is reminiscent of their distribution as degree modifiers of adjectives; the primed examples show that they must follow the modified element in this function.

| a. | Hij | heeft | <genoeg> | boeken <genoeg>. | |

| he | has | enough | books |

| a'. | Hij | is | <*genoeg> | oud <genoeg>. | |

| he | is | enough | old |

| b. | Hij | heeft | <zat> | boeken <zat>. | |

| he | has | plenty | books |

| b'. | Dat is | <*zat> | moeilijk <zat>. | |

| that is | enough | difficult |

The quantifiers genoeg and voldoende (but not zat) can be negated, in which case they express sentential negation. The examples in (270) show that they differ in that sentential negation is expressed by the negative adverb niet in the case of genoeg, but by the prefix on- in the case of voldoende. The fact that negation is morphologically expressed on the quantifier itself in the case of voldoende suggests that the negative adverb niet forms a constituent with the quantifier genoeg, and there is indeed some evidence for this; the presence of niet in (270a') excludes postnominal placement of genoeg, which may be due to the fact that the quantifier is now complex.

| a. | Hij | heeft | niet | genoeg | boeken. | |

| he | has | not | enough | books | ||

| 'He doesnʼt have enough books.' | ||||||

| a'. | * | Hij | heeft | niet | boeken | genoeg. |

| he | has | not | books | enough |

| b. | Hij | heeft | onvoldoende | boeken. | |

| he | has | not.enough | books | ||

| 'He doesnʼt have enough books.' | |||||

Even if niet genoeg is a constituent in (270a), this does not have to be true in all cases. This is shown by the fact that (271a), which has basically the same meaning as (270a), allows topicalization of the noun phrase genoeg boeken with stranding of the negative adverb niet. The obvious conclusion that sentential negation can be expressed externally to the quantified noun phrase is also supported by example (271b), in which sentential negation is realized on the temporal adverb nooitnever.

| a. | Genoeg boeken | heeft | hij | niet. | |

| enough books | has | he | not |

| b. | Hij | heeft | nooit | genoeg boeken. | |

| he | has | never | enough books |

For completeness’ sake, example (272) shows that sentential negation can also be expressed within the noun phrase by means of the negative article/quantifier geenno; however, this case contrasts sharply with (270a) in that the quantifier must be placed postnominally.

| Hij | heeft | geen | <*genoeg> | boeken <genoeg>. | ||

| he | has | no | enough | books | ||

| 'He doesnʼt have enough books.' | ||||||

The cases in (270a&b) express that the cardinality of the set denoted by the noun remains below the lower bound of the contextually determined norm. It is also possible to express that the cardinality exceeds the upper bound of this norm by using the complex phrase meer dan genoeg/voldoendemore than enough; zat sounds marked although we found some cases on the internet with non-count nouns (e.g. meer dan zat ellende/pleziermore than enough misery/fun). Section 20.2.5 will discuss examples such as (273a) in more detail.

| a. | Hij | heeft | meer dan | genoeg/voldoende | boeken. | |

| he | has | more than | enough | books | ||

| 'He has more than enough books.' | ||||||

| b. | ? | Hij | heeft | meer dan zat | boeken. |

| he | has | more than plenty | books |

To conclude this subsection, note that voldoende and genoeg are used not only as degree modifiers of nouns, but also as degree modifiers of adjectives; cf. A26.1.3.

Like most existential quantifiers, the degree quantifiers veel and weinig are not normally used as independent arguments: example (274b) is acceptable, due to the presence of [NP e] licensed by quantitative er, but example (274c) with a truly independent quantifier is unacceptable.

| a. | Er | rijden | veel/weinig fietsen | op straat. | |

| there | drive | many/few bikes | on street | ||

| 'There are many/few bikes on the street.' | |||||

| b. | Er | rijden | er [DP | veel/weinig [NP e]] | op straat. | Q-er construction | |

| there | drive | er | many/few | on street |

| c. | * | Er | rijden [DP | veel/weinig] | op straat. | independent degree-Q |

| there | drive | many/few | on street |

Things are different, however, when we are dealing with non-count nouns. Since the quantitative er construction requires the empty NP to be plural, it is not really surprising that example (275b) is excluded. However, unlike (274c), (275c) is perfectly acceptable on a mass interpretation: veel/weinig can refer to a certain amount of liquid (e.g. wine).

| a. | Er | zit | veel/weinig wijn | in de fles. | |

| there | is | much/little wine | in the bottle |

| b. | * | Er | zit | er | [veel/weinig [e]] | in de fles. | Q-er construction |

| there | is | er | much/little | in the bottle |

| c. | Er | zit | veel/weinig | in de fles. | independent degree-Q | |

| there | is | much/little | in the bottle |

Note that the judgments on the examples in (274) and (275) remain the same when veel and weinig are modified by degree modifiers like ergvery or tetoo or replaced by their comparative forms meermore and minderless. Replacement by the superlative forms (het) meestthe most and (het) minstthe least is excluded in these examples, but this is for the independent reason that definite noun phrases are not possible in quantitative/expletive er constructions.

We can capture the differences between the examples in (274) and (275) by means of the structural representations in (276), which are based on the general format of our earlier structural analysis of quantified nominal phrases of the type veel/weinig N. The (a)-representations assume that the degree quantifiers are modifiers of the silent nouns number and amount (cf. Kayne 2002), which head the complex quantifier in the specifier position of NumP. The feature values [+plural] and [Ø] of the Num-head further indicate that mass nouns differ from count nouns in that they are not specified for number (cf. Mattens 1970). The (b)-representations express that the empty NP in the quantitative er construction must be licensed by a Num-head specified for number, thus accounting for the acceptability contrast between (274b) and (275b). The (c)-examples assume the presence of the silent noun substance, which is incompatible with a Num-head specified for number.

| a. | [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig number] [Numplural [NP boeken]]]]] |

| a'. | [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig amount] [NumØ [NP wijn]]]]] |

| b. | .. er .. [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig number] [Numplural [NP e]]]]] |

| b'. | * | .. er .. [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig amount] [NumØ [NP wijn]]]]] |

| c. | * | [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig number] [Numplural [NP substance]]]]] |

| c'. | [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig amount] [NumØ [NP substance]]]]] |

The (c)-representations in (276) suggest that the independently used quantifiers can only alternate with noun phrases headed by a [-count] noun, but the fact that the sentences in (277b&c) can be used in the same context shows that this is not correct. The two examples differ in that the subject in (277b) is used to refer to an indeterminate number of books (say about 100), while the subject in (277c) is used to refer to an indeterminate amount of books (e.g. a large pile). This suggests that it is not so much the feature [±count] of the noun that is relevant, but the question of whether the noun heading the quantificational phrase in the specifier of NumP is number or amount. If so, the (c)-representations in (276) correctly predict that the difference in interpretation is reflected in the number agreement on the verb: the subject in (277b) triggers plural agreement on the verb while the subject in (277c) triggers singular agreement.

| a. | Er | liggen | nog | veel boeken | op zolder. | |

| there | lie | still | many books | in the.attic | ||

| 'There are still many books in the attic.' | ||||||

| b. | Er | liggen/*ligt | er | nog | [veel [e]] | op zolder. | Q-er construction | |

| there | lie/lies | er | still | many books | in the.attic |

| c. | Er | ligt/*liggen | nog | veel | op zolder. | independent degree-Q | |

| there | lies/lie | still | much | in the attic |

There is another difference between quantitative er constructions and independently used degree quantifiers: the empty NPs in quantitative er constructions are anaphoric in the sense that their interpretation depends on the preceding context; in (274b) the empty NP must be interpreted as “bikes” and in (277b) as “books’. The independently used degree quantifiers may or may not be anaphoric: veel/weinig may refer to a certain quantity of wine in (275c) or to a certain number of books in (277c), but in both cases the independently used degree quantifier may also refer to a certain number of different (possibly unidentified) things.

So far we have only considered examples with inanimate subjects. If we compare the examples in (277) with the count noun boekenbooks with the examples in (278) with the count noun kinderenchildren, we see that they behave in a similar way with regard to the quantitative er construction, but differently when it comes to the independent use of the degree quantifier: the independent use is impossible with inanimate NPs, but possible with NPs referring to people (as well as certain animals), provided that the quantifier is inflected with –en. Furthermore, the inflected quantifiers velen and weinigen in (278c) differ from the bare quantifier veel in (275c) and (277c) in that they trigger plural agreement on the finite verb. Note that some people consider weinigen in (277c) to be obsolete.

| a. | Er | lopen | veel/weinig | kinderen | op straat. | |

| there | walk | many/few | children | in the.street |

| b. | Er | lopen | er | [veel/weinig [e]] | op straat. | |

| there | walk | er | many/few | in the.street |

| c. | Er | lopen | velen/slechts weinigen | op straat. | |

| there | walk | many/only few | in the.street |

The two differences can be accounted for if we adopt our earlier assumption from Section 20.1.1.6, sub IIIC2, that plural forms of the quantifiers in (278c) can arise thanks to the presence of the silent noun persoon. If so, the subjects in the examples in (278) can be given the structural representations in (279).

| a. | [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig number] [Numplural [NP kinderen]]]]] |

| b. | .. er .. [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig number] [Numplural [NP e]]]]] |

| c. | [DP Ø [NumP | [veel/weinig number] [Numplural [NP persoon-en]]]]] |

The difference in acceptability between (279c) and (276c) implies that the silent noun persoon is different from the silent noun substance in that it is a count noun; it also brings with it that the degree quantifiers are inflected with –en, which is the result of merging it with the plural suffix of the silent noun persoon.

Note in passing that the analysis in (279) confirms the suggestion in the 2012 edition of this work that there is no direct relation between the independent use of the degree quantifiers in (280c) and their use as attributive modifiers of the noun phrases in (280a&b). However, this still leaves the acceptability of vele in (280b) as a problem, because attributive modifiers are generally not possible in quantitative er constructions; cf. *Er lopen er [vrolijke e] op straat (intended reading: “There are happy people walking in the street”).

| a. | Er | lopen | vele/*?weinige | mensen | op straat. | |

| there | walk | many/few | people | in the.street |

| b. | Er | lopen | er | [vele/*?weinige [e]] | op straat. | |

| there | walk | er | many/few | in the.street |

| c. | Er | lopen | velen/slechts weinigen | op straat. | |

| there | walk | many/only few | in the.street |

The fact that the independently used quantifiers veel and weinig in the previous examples function as the subject of expletive er constructions shows that they can be used as weak noun phrases. However, they can also be used as strong noun phrases, as shown for veel in example (281a); for completeness’ sake, this example also shows that the superlative het meeste can be used as an independent argument (note that het is not an article in this case, but part of the superlative). The remaining examples in (281) show that such independently used quantifiers can be used in all regular argument positions accessible to inanimate noun phrases, i.e. as direct object or as complement of a preposition.

| a. | Veel/het meeste | ligt | nog | op zolder. | subject | |

| much/most | lies | still | in the.attic | |||

| 'A lot/Most still lies in the attic.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan heeft | veel/het meeste op zolder opgeborgen. | direct object | |

| Jan has | much/most in the.attic prt.-stored | |||

| 'Jan has stored a lot/most in the attic.' | ||||

| c. | Marie heeft | over veel/het meeste | nagedacht. | PP-object | |

| Marie has | about much/most | prt.-thought | |||

| 'Marie has thought about a lot/most (things).' | |||||

The same is true for the independently used quantifiers velen and weinigen. Example (282a) first shows that these quantifiers can be used not only as weak but also as strong noun phrases. The remaining examples show that these quantifiers can be used in all regular argument positions accessible to [+human] noun phrases, i.e. as (in)direct object or as complement of a preposition.

| a. | Velen/Slechts weinigen | hebben | geklaagd | over de kou. | subject | |

| many/only few | have | complained | about the cold | |||

| 'Many/Only a few have complained about the cold.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | heb | daar | velen/slechts weinigen | ontmoet. | direct object | |

| I | have | there | many/only few | met | |||

| 'I have met many/only a few there.' | |||||||

| c. | Ik | heb | velen/slechts weinigen | een kaart | gestuurd. | indirect object | |

| I | have | many/only few | a postcard | sent | |||

| 'I have sent many/only a few a postcard.' | |||||||

| d. | Ik | heb | aan velen/slechts weinigen | een kaart | gestuurd. | PP-object | |

| I | have | to many/only few | a postcard | sent | |||

| 'I have sent a postcard to many/only a few.' | |||||||

The examples in (283) and (284) show that veel/weinig can also be used as the predicate in a copular construction or as a measure phrase with verbs like kosten. In such cases, veel and weinig can also be replaced by their comparative or superlative form; the latter can optionally take an -e ending.

| a. | Dat | is | erg | veel/weinig. | |

| that | is | very | much/little | ||

| 'That is quite a lot/very little.' | |||||

| b. | Dat | is meer/minder | dan | je | nodig | hebt. | |

| that | is more/less | than | you | need | have | ||

| 'That is more/less than you need.' | |||||||

| c. | Dat is het meest(e)/minst(e). | |

| that is the most/least | ||

| 'That is the most/least I can do.' |

| a. | Dat | kost/weegt | veel/weinig. | |

| that | costs/weighs | much/little |

| b. | Dit boek | kost | meer/minder | (dan dat boek). | |

| this book | costs | more/less | than that book |

| c. | Dat boek | kost | het meest(e)/minst(e). | |

| that book | costs | the most/least |

The degree modifiers expressing that the cardinality of the intersection satisfies a contextually determined norm behave more or less like uninflected veelmany and weinigfew. If genoeg, voldoende and zat trigger plural agreement on the finite verb, they must be accompanied by quantitative er; this implies that these examples show that genoeg, voldoende and zat cannot be used as independent arguments referring to a collection of entities of a contextually determined kind.

| a. | Er | lopen | genoeg/voldoende/zat jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | enough/enough/plenty boys | in the.street |

| b. | Er | lopen | er | [genoeg/voldoende/zat [e]] | op straat. | |

| there | walk | er | enough/enough/plenty | in the.street |

| c. | * | Er | lopen | genoeg/voldoende/zat | op straat. |

| there | walk | enough/enough/plenty | in the.street |

However, if these elements trigger singular agreement, quantitative er cannot be realized. Like veel/weinig in (275c), the quantifiers in (286c) can then be construed with a mass interpretation; they refer e.g. to a certain quantity of wine, or to a set of discrete entities of a disparate or unidentified kind.

| a. | Er | zit | genoeg/voldoende/zat | wijn | in de fles. | |

| there | is | enough/enough/plenty | wine | in the bottle |

| b. | * | Er | zit | er | [genoeg/voldoende/zat [e]] | in de fles. |

| there | is | er | enough/enough/plenty | in the bottle |

| c. | Er | zit | genoeg/voldoende/zat | in de fles. | |

| there | is | enough/enough/plenty | in the bottle |

This suggests that the examples in (285) can be analyzed along the lines of the silent noun number and those in (286) along the lines of the silent noun amount; we are dealing with the representations in (276) with genoeg/voldoende/zat instead of weinig/veel.

This subsection discusses the use of degree quantifiers as independent arguments. As in Subsection I, we will discuss the high-degree/low-degree quantifiers veel and weinig, and the degree quantifiers voldoende, genoeg, and zat in separate subsections.