- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This chapter focuses on the use of the predeterminers alall and heelall/whole, which are illustrated in the primeless examples of (1). These predeterminers will be discussed in relation to their “inflected” counterparts alle and hele in the nearly equivalent constructions in the primed examples. Note that we will use the notion of predeterminer al/heel descriptively, i.e. to express that the elements in question linearly precede a definite article or a possessive/demonstrative pronoun in the noun phrase; contrary to what is suggested in Van de Velde (2009: 253, 293-4), the term predeterminer has no theoretical significance and is certainly not intended to denote the members of a separate (functional) word class. The same applies to the use of the notion of postdeterminer heel, which we will use to refer to the inflected form of heel in (1b').

| a. | Al de boeken | zijn | verkocht. | ||||

| all the books | have.been | sold | |||||

| 'All books are sold.' | |||||||

| a'. | Alle boeken | zijn | verkocht. | ||||

| all books | have.been | sold | |||||

| 'All books are sold.' | |||||||

| b. | Ze | kletsen | heel de dag | ||||

| they | chatter | whole the day | |||||

| 'They chatter all day.' | |||||||

| b'. | Ze | kletsen | de hele dag. | ||||

| they | chatter | the whole day | |||||

| 'They chatter all day.' | |||||||

The predeterminers al and heel as well as their alternants in the primed examples of (1) have in common that they function as universal quantifiers in a somewhat extended sense. A semantico-syntactic property of universal quantifiers is that they can be modified by approximative modifiers like bijnanearly and vrijwelalmost; cf. Section 20.2.5. This is shown in (2) for the universal quantifier alleseverything, and its negative existential quantifier niets, which can be represented as a universal quantifier followed by negation; cf. the equivalence rule ¬∃x φ ↔ ∀x ¬φ.

| a. | Jan heeft | bijna/vrijwel | alles | verkocht. | |

| Jan has | nearly/almost | everything | sold | ||

| 'Jan has sold nearly everything.' | |||||

| b. | Jan heeft | bijna/vrijwel | niets | verkocht. | |

| Jan has | nearly/almost | nothing | sold | ||

| 'Jan has sold almost everything.' | |||||

The primeless examples in (3) show that the predeterminers al and heel have the same modification possibilities, and the primed examples show the same for inflected alle and hele.

| a. | Jan heeft | bijna/vrijwel | al de boeken | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | nearly/almost | all the books | read |

| a'. | Jan heeft | bijna/vrijwel | alle boeken | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | nearly almost | all books | read |

| b. | Jan heeft | bijna/vrijwel | heel het huis | schoongemaakt. | |

| Jan has | nearly/almost | whole the house | clean.made |

| b'. | Jan heeft | bijna/vrijwel | het hele huis | schoongemaakt. | |

| Jan has | nearly/ almost | the whole house | clean.made |

There are some subtle differences in meaning between the primed and the primeless examples; al de boeken in (3a), for instance, refers to a contextually determined set of books, while alle boeken in (3a') can also have a generic reading in that it refers to the set of books in the speaker’s conception of the universe, i.e. to all existing books; heel het huis in (3b) refers to the distinctive parts that make up a house (living room, bedrooms, kitchen, bathroom, attic, etc.), while het hele huis in (3b') can also refer to the house as a unit, e.g. the house as seen from the outside.

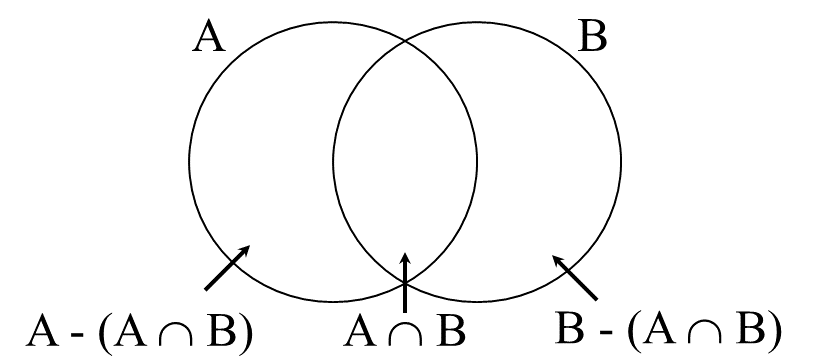

That alall is a universal quantifier is also clear from its meaning: in terms of Figure 1 from Section 15.1.2, sub IIA, examples like Al de/Alle boeken zijn verkochtAll the books have been sold in (1) express that all members of denotation set A of the subject noun phrase are properly included in denotation set B of the verb phrase, i.e. that A - (A ∩ B) is empty; cf. the discussion in Section 20.2.1.

The semantics of heel, which will be discussed in more detail in Section 21.2.1, is somewhat different. In an example such as Het hele huis is schoonThe whole house is clean, the subject refers to the parts that make up the house in question and the predeterminer heel indicates that the predicate schoon applies to all these parts. Now, if we take set A in Figure 1 to refer to the relevant parts of the house, heel also expresses that A - (A ∩ B) is empty.

Related to the fact that al and heel quantify over a different kind of set is the fact that the two predeterminers are generally in complementary distribution. This is illustrated in (4) for count nouns: since the predeterminer al quantifies over a set of entities with cardinality greater than one, the head noun of the noun phrase it quantifies is usually plural; since the predeterminer heel quantifies over the parts of an entity, the head noun is typically singular.

| a. | Jan heeft | al de koeken/*koek | opgegeten. | |

| Jan has | all the cookies/cookie | prt.-eaten |

| b. | Jan heeft | heel de taart/*taarten | opgegeten. | |

| Jan has | whole the cake/cakes | prt.-eaten |

The use of predeterminers is not very common in present-day Dutch. This was already mentioned for heel in the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal, where it was mentioned that it was already restricted to the more elevated and poetic registers at the time when the lemma heel was written (1901-1912). In a review of this chapter in the first edition of SoD, Van de Velde (2014;§2) further claimed that the use of the predeterminer al is also in decline and on the verge of becoming a historical relic in combination with definite articles (but less so with possessive and demonstrative pronouns): his data suggests that the construction with al de should have become extinct in the first decade of the 21st century (see his Figure 1). We believe that the ubiquity of the sequence al de + Npl on Dutch web pages shows the opposite: for example, a Google search (2023/6/18) for [al de leugens] all the lies alone yielded nearly 100 results (including 24 manually checked cases from the 12 months prior to the search). There is therefore no reason to exclude the study of predeterminers from this grammar of contemporary language as obsolete usage: in our view, the predeterminers al and heel are still part of the core grammar.

With this brief introduction and apology, we have set the stage for a detailed discussion of alall and heelwhole in Section 21.1 and Section 21.2, respectively. We will conclude this chapter in Section 21.3 with a brief note on focus particles such as alleenonly and ooktoo, which can also occur in predeterminer position; cf. Alleen/Ook de boeken zijn verkochtOnly/Also the books have been sold.