- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This section discusses a number of co-occurrence restrictions on the coordinands of a coordinate structure. Chomsky (1957), Schachter (1977), and many others have noted that the coordinands must be of the “same kind” as the coordinate structure as a whole. Subsection I will make this more precise by showing that the coordinands are subject to the co-occurrence restrictions in (108).

| Co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands: | ||

| Coordination is possible only if the coordinands can have the same syntactic functions and can occur in the same syntactic positions as the coordinate structure as a whole. |

Subsection II continues by showing that coordinate structures are usually islands for movement, which is known as the coordinate structure constraint; the formulation in (109) is adapted from Ross (1967 (4.84)).

| Coordinate structure constraint: | ||

| Extraction from a coordinate structure is impossible: neither the coordinands themselves nor any phrase contained in them can be extracted from the coordinate structure by movement. |

There is a well-known exception to this general rule, known as across-the-board movement; we will argue that the co-occurrence restrictions in (108) are capable of accounting for the cases covered by (109) as well as the supposed exceptional cases of across-the-board movement. This renders the coordinate structure constraint superfluous for providing an adequate description; thus, the real question is how to properly account for the co-occurrence restrictions in (108).

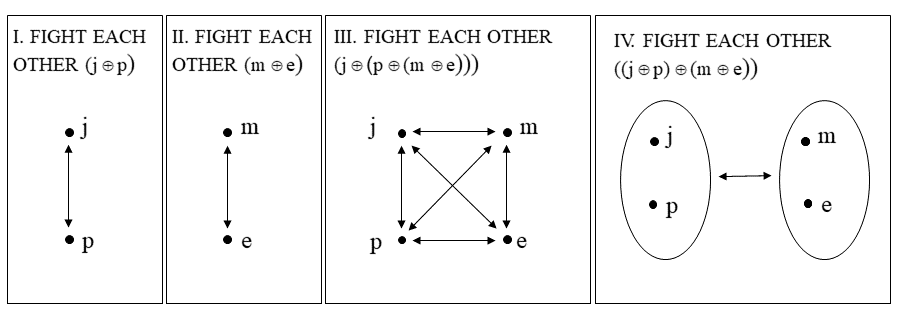

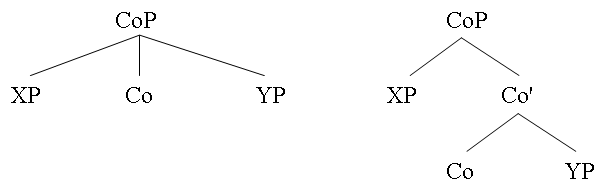

Subsection III continues by discussing the internal make-up of coordinate structures, and will argue that coordinators are two-place linkers, just like logical conjunction and disjunction in formal semantics. It implies that polyadic coordinate structures (i.e. structures with more than two coordinands) are recursive in the sense that coordinate structures can be embedded in (i.e. be used as coordinands of) larger coordinate structures; this implies that polyadic coordinate structures are hierarchically structured. Subsection IV even goes a step further by showing that there are reasons to assume that the same holds for dyadic coordinate structures, since the two coordinands may exhibit different syntactic behavior: for example, the first coordinand can enter into a relation with an element external to the coordinate structure, while the second cannot.

- I. Co-occurrence restrictions

- II. Coordinate structure constraint and across-the-board movement

- III. Embedding/recursivity

- A. Associativity and commutativity of conjunction and disjunction

- B. Hierarchically ordered coordinate structures

- C. Hierarchical coordinate structures: word order and meaning

- D. Hierarchical coordinate structures and prosody

- E. Ambiguities in triadic coordinate structures with enand

- F. Ambiguities in larger polyadic coordinate structures with enand

- G. A potential problem: polyadic coordinate structures with nochnor

- A. Associativity and commutativity of conjunction and disjunction

- IV. Are coordinate structures binary branching?

Chomsky (1957: 35-7) noted that coordination is a very useful test for establishing constituency, since it is only possible if the coordinands are constituents of the same kind. For example, the postnominal modifiers of boekbook in (110a&b) can easily be coordinated, as shown by (110c). The examples in (111) show the same thing with restrictive relative clauses.

| a. | Marie las | [boeken | [over Hitler]]. | PP-modifier | |

| Marie read | books | about Hitler |

| b. | Marie las | [boeken | [over Nazi-Duitsland]]. | PP-modifier | |

| Marie read | books | about Nazi.Germany |

| c. | Marie las | [boeken | [[over Nazi-Duitsland] | en | [over Hitler]]]. | |

| Marie read | books | about Nazi.Germany | and | about Hitler |

| a. | [De man | [die hier net was]] | is een bekend schrijver. | |

| the man | who here just was | is a well-known writer | ||

| 'The man who was here just now is a well-known writer.' | ||||

| b. | [De man | [die Russisch sprak]] | is een beroemd schrijver. | |

| the man | who Russian spoke | is a famous writer | ||

| 'The man who spoke Russian is a famous writer.' | ||||

| c. | [De man | [[die hier net was] | en [die Russisch sprak]]] | is een beroemd schrijver. | |

| the man | who here just was | and who Russian spoke | is a famous writer | ||

| 'The man who was here just now and who spoke Russian is a famous writer.' | |||||

However, it is not a trivial matter to decide whether two constituents are of the “same kind” or not. This subsection discusses three aspects that may be relevant for determining this.

It has been suggested that the coordinands must be of the same syntactic category. This would explain the contrast between the (110c) and (112c): while coordination of two PP-modifiers is possible, coordination of a postnominal PP and a relative clause is not, even though they both clearly function as modifiers of the noun phrases.

| a. | Marie las | [boeken | [over Hitler]]. | PP-modifier | |

| Marie read | books | about Hitler |

| b. | Marie las | [boeken | [die | Els had | gekocht]]. | relative clause | |

| Marie read | books | which | Els had | bought |

| c. | * | Marie las | [boeken | [[over Hitler] | en | [die | Els had | gekocht]]]. |

| Marie read | books | about Hitler | and | which | Els had | bought |

However, the examples in (113) show that categorial identity is not sufficient for coordination, since it is not possible to coordinate two postnominal modifiers of the same category if their meaning contributions differ: while the PP-modifier over Hitler specifies the subject matter of the books, the van-PP refers to their author or possessor, and coordination is usually highly questionable.

| a. | Marie las | [boeken | [over Hitler]]. | subject matter | |

| Marie read | books | about Hitler |

| b. | Marie las | [boeken | [van | Els]]. | agent or possessor | |

| Marie read | books | by/of | Els |

| c. | * | Marie las | [boeken | [[over Hitler] | en | [van | Els]]]. |

| Marie read | books | about Hitler | and | by/of | Els |

The difference in meaning contribution of the two PP-modifiers in (113) is also reflected in the fact that they can co-occur. Example (114a) first shows that the PP-modifiers in (110), which have an identical semantic relation to the modified noun, cannot co-occur as independent phrases within a single noun phrase. Example (114b), on the other hand, shows that PP-modifiers such as the over- and van-PP in (113), which have different meaning contributions, can co-occur as independent phrases within a single noun phrase; this suggests that they have different syntactic functions and that it is this fact that blocks coordination. If so, we can give a similar account of the unacceptability of (112c), in which a PP-modifier and a relative clause are coordinated, because (114c) shows that they can also co-occur as independent phrases within a single noun phrase.

| a. | * | Marie las | [[boeken | [over Hitler]] | [over Nazi-Duitsland]]. |

| Marie read | books | about Hitler | about Nazi.Germany |

| b. | Marie las | [[boeken | [over Hitler]] | [van Els]]. | |

| Marie read | books | about Hitler | of/by Els |

| c. | Marie las | [[boeken | [over Hitler]] | [die | Els had | gekocht]]. | |

| Marie read | books | about Hitler | which | Els had | bought |

The examples in (115) show that categorial identity is not only insufficient, but actually not necessary for coordination to be possible: coordination of an adjectival and an adpositional complementive is possible; and the same holds for an adjectival and a prepositional adverbial phrase.

| a. | Jan is [AP | moe]. | adjectival complementive | |

| Jan is | tired |

| a'. | Jan is [PP | in de war]. | prepositional complementive | |

| Jan is | confused |

| a''. | Jan is | [[moe] | en | [in de war]]. | |

| Jan is | tired | and | confused |

| b. | Jan at [AP | gretig]. | adjectival manner adverbial | |

| Jan ate | greedily |

| b'. | Jan at [PP | met smaak]. | prepositional manner adverbial | |

| Jan ate | with relish |

| b''. | Jan at | [[gretig] | maar | [met smaak]]. | |

| Jan ate | greedily | but | with relish |

It has been suggested that the acceptability of (115a''&b'') can be reconciled with the categorial identity requirement by assuming that we are dealing with coordination of predicative phrases (i.e. PredPs) in (115a'') and adverbial phrases (i.e. AdvPs) in (115b''). This may be undesirable, since it seems to be based on mixing the notions of syntactic category and syntactic/semantic function. Moreover, it is not necessary, since the simpler alternative in (116) presents itself (assuming that the notion of adverbial function is used to cover a set of different syntactic functions, as is claimed in Chapter V8 on independent grounds); see also Dik (1968:25), Haeseryn et al. (1997:1450), Hendriks (2001b), and many others.

| Co-occurrence restriction on coordinands (to be revised): | ||

| Coordination is possible only if the coordinands can have the same syntactic functions as the coordinate structure as a whole. |

Generalization (116) predicts linking of adjectival and nominal predicates also to be possible. This is indeed confirmed, although there seem to be additional restrictions that are not fully understood. For instance, the examples in (117) have been taken to show that such linking is possible only if the nominal predicate is in some sense “gradable”; cf. Goodall (1987:45).

| a. | Jan is | [[aardig] | en | [een (enorme) steun voor zijn moeder]]. | |

| Jan is | kind | and | an immense support for his mother | ||

| 'Jan is kind and a great help to his mother.' | |||||

| b. | Jan is [[aardig] | en | [een | $(*enorme) | taalkundige]]. | |

| Jan is kind | and | an | immense | linguist | ||

| Compare: 'Jan is kind and very much a linguist.' | ||||||

The examples in (118) suggest, however, that the evaluative nature of the nominal predicates may also play a role: the use of the adversative coordinator maar is possible with the nominal predicate een leugenaara liar because its negative connotation contrasts with the positive property denoted by the adjective aardigkind, but impossible with the nominal predicate een steuna support because this predicate has no negative connotation.

| a. | Jan is | [[aardig] | en/$maar | [een (enorme) steun]]. | |

| Jan is | kind | and/but | an immense support |

| b. | Jan is | [[aardig] | maar/$en | [een | (enorme) | leugenaar]]. | |

| Jan is | kind | but/and | an | immense | liar | ||

| 'Jan is kind but (very much) a liar.' | |||||||

The examples in (119) show that [+human] nouns can easily be coordinated more generally with adjectives denoting some property typically (dis)associated with them: if the property is expected for the persons denoted by the noun, the coordinator en is often followed by the adverbial dustherefore, but if the adjective denotes an unexpected property, the adversative coordinator maarbut is used.

| a. | Jan is [[rechter] | en | %(dus) | [streng]]. | |

| Jan is a.judge | and | therefore | stern |

| b. | Jan is [[een taalkundige] | maar | [slordig in zijn taalgebruik]]. | |

| Jan is a linguist | but | sloppy in his language use |

Since we have little more to say about the factors affecting the acceptability of linking of adjectival and nominal predicates, we leave this issue for future research; for the moment, it suffices to note that the acceptable examples in (117)-(119) show that such linking is syntactically allowed.

An apt illustration of the co-occurrence restriction on coordinands in (116) is given in (120); although the verb wegento weigh can select a referential noun phrase such as de appelsthe apples in (120a) or a non-referential noun phrase such as 70 kilo ’70 kilos’ in (120b), the coordinate structure in (120c) is impossible. This is probably due to the fact that the two noun phrases have different syntactic functions. The referential noun phrase clearly has the function of a direct object, as can be seen from the fact that it allows passivization: De appels worden gewogenthe apples are weighed. The non-referential noun phrase does not function as a direct object because it does not allow passivization: *Er wordt/worden 70 kilo gewogen. Example (120c) is therefore correctly excluded by restriction (116).

| a. | Jan weegt | de appels. | |

| Jan weighs | the apples |

| b. | Jan weegt | 70 kilo. | |

| Jan weighs | 70 kilos |

| c. | * | Jan weegt | [[de appels] | en | [70 kilo]]. |

| Jan weighs | the apples | and | 70 kilos |

Assuming that the notion of adverbial function is an umbrella term, the formulation in (116) also correctly predicts that, for example, place and time adverbials cannot be coordinated. This accounts for the acceptability contrast in the (a)-examples in (121), but leaves puzzling why examples such as (121b) are acceptable; cf. Schachter (1977:91). We will assume that the latter case is a fixed collocation because this example refers to a single (prospective) eventuality at a certain time and place, whereas clauses with coordinated time or place adverbials usually refer to different eventualities: cf. Ik ontmoet Jan morgen en volgende week maandagI will meet Jan tomorrow and Monday next week. The claim that we are dealing with a collocation can perhaps also be supported by the fact that the order of the two coordinands is more or less fixed, since at least some speakers prefer the order in (121b) to the order in (121b').

| a. | Ik | ontmoet | Jan | [volgende week] | [in Amsterdam]. | |

| I | meet | Jan | next week | in Amsterdam | ||

| 'I will meet Jan in Amsterdam next week.' | ||||||

| a'. | * | Ik | ontmoet | Jan | [[volgende week] | en | [in Amsterdam]]. |

| I | meet | Jan | next week | and | in Amsterdam |

| b. | [Waar | en | wanneer] | ontmoet | je | Jan? | |

| where | and | when | meet | you | Jan | ||

| 'Where and when will you meet Jan?' | |||||||

| b'. | % | [Wanneer | en | waar] | ontmoet | je | Jan? |

| when | and | where | meet | you | Jan |

The co-occurrence restriction on coordinands in (116), which states that the coordinands must be able to have the same syntactic function as the coordinate structure as a whole, differs from the categorial identity requirement in that it correctly allows for examples such as Jan is [[AP moe] en [PP in de war]] Jan is tired and confused in (115). In other respects, however, it seems to cover more or less the same ground, since many syntactic functions are prototypically expressed by phrases of a particular syntactic category. Nevertheless, the formulation in (116) still seems to be inadequate, since it wrongly predicts that nominal and clausal phrases can be coordinated in the function of subject or object; the primed examples in (122) are therefore wrongly predicted to be fully acceptable.

| a. | [Dat boek]/[Dat Jan komt] | is leuk. | subject | |

| that book/ that Jan comes | is nice |

| a'. | ?? | [[Dat boek] | en | [dat Jan komt]] | is leuk. |

| that book | and | that Jan comes | is nice |

| b. | [Dat boek]/[Dat Jan komt] | vind | ik | leuk. | object | |

| that book/that Jan comes | consider | I | nice |

| b'. | ?? | [[Dat boek] | en | [dat Jan komt]] | vind | ik | leuk. |

| that book | and | that Jan comes | consider | I | nice |

That coordinate structures consisting of a noun phrase and a clause do not often occur as a subject or object is not surprising: in the prototypical case, the coordinands arguably occupy different positions when used in the same function. The primeless examples in (123) show that argument clauses are usually preceded by the anticipatory pronoun hetit and appear in postverbal position, i.e. in a position where a nominal subject cannot appear. The primed examples show that argument clauses are not easily possible in the preverbal positions normally occupied by the nominal arguments.

| a. | dat | het | leuk | is | [dat Jan komt]. | subject | |

| that | it | nice | is | that Jan comes |

| a'. | dat | dat boek/??[dat Jan komt] | leuk | is. | |

| that | that book/that Jan comes | nice | is |

| b. | dat | ik | het | leuk | vind | [dat Jan komt]. | object | |

| that | I | it | nice | consider | that Jan comes |

| b'. | dat | ik | dat boek/??[dat Jan komt] | leuk | vind. | |

| that | I | that book/that Jan comes | nice | consider |

As nominal and clausal arguments occupy different positions in the clause we may account for the markedness of primed examples in (122) by adding to the generalization in (116) that the coordinands should be able to occur in the same syntactic positions as the coordinate structure as a whole.

| Co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands (to be revised): | ||

| Coordination is possible only if the coordinands can have the same syntactic functions and can occur in the same syntactic positions as the coordinate structure as a whole. |

The formulation in (124) predicts that the coordinands of a coordinate structure that functions as an argument can all be nominal or all be clausal, as in as (125a-b), but cannot be easily mixed: example (122a'), repeated as (125c), is predicted to be at best equally acceptable as (123a') with a subject clause.

| a. | [[Dat boek] | en | [die plaat]] | zijn | leuk. | |

| that book | and | that record | are | nice |

| b. | Het | is leuk | [[dat Jan komt] | en | [dat | hij | een lezing | geeft]]. | |

| it | is nice | that Jan comes | and | that | he | a talk | gives | ||

| 'It is nice that Jan is coming and that he will give a talk.' | |||||||||

| c. | ?? | [[Dat boek] | en | [dat Jan komt]] | is leuk. |

| that book | and | that Jan comes | is nice |

The same holds for object clauses; example (122b'), repeated as (126c), is predicted to be at best equally acceptable as (123b') with an object clause.

| a. | Ik | vind | [[dat boek] | en | [die plaat]] | leuk. | |

| I | consider | that book | and | that record | nice |

| b. | Ik | vind | het | leuk | [[dat Jan komt] | en | [dat | hij | een lezing | geeft]]. | |

| it | consider | it | nice | that Jan comes | and | that | he | a talk | gives | ||

| 'I consider it nice that Jan is coming and that he will give a talk.' | |||||||||||

| c. | ?? | [[Dat boek] | en | [dat Jan komt]] | vind | ik | leuk. |

| that book | and | that Jan comes | consider | I | nice |

Note that the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands in (124) do not categorically exclude the coordination of nominal and clausal constituents. For example, Section V5.1.2.3 has shown that factive verbs such as betreurento regret do allow object clauses in preverbal position, and they do indeed allow coordination of a nominal and clausal object.

| a. | dat | Jan | [zijn vroege vertrek] | erg | betreurt. | |

| that | Jan | his early departure | much | regrets |

| b. | dat | Jan | [dat | hij | niet | kan | spreken] | erg betreurt. | |

| that | Jan | that | he | not | can | speak | much regrets |

| c. | dat | Jan | [[zijn vroege vertrek] | en | [dat hij niet kan spreken]] | erg betreurt. | |

| that | Jan | his early departure | and | that he not can speak | much regrets | ||

| 'that Jan deeply regrets his early departure and that he cannot give a talk.' | |||||||

Another “mixed” case allowed by the formulation (124) is given in (128): the first two examples show that nominal and clausal adverbial phrases of time can both occur in preverbal position, and the third example shows that they can also be coordinated.

| a. | dat | Jan ʼs morgens | onder de douche | gaat. | |

| that | Jan in.the.morning | under the shower | goes |

| b. | dat | Jan [nadat | hij | gesport | heeft] | onder de douche | gaat. | |

| that | Jan after | he | exercised | has | under the shower | goes |

| c. | dat | Jan [[ʼs morgens] | en | [nadat | hij gesport heeft]] | onder de douche gaat. | |

| that | Jan in.the.morning | and | after | he exercised has | under the shower goes | ||

| 'that Jan takes a shower in the morning and after he has exercised.' | |||||||

The literature mentions a number of apparent counterexamples to the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands in (124), which we will discuss next; see Zhang (2010:§3.3.1) for an overview and references. Consider the English examples in (129), which are taken to show that “mixed” coordinate structures of the form [NP and clause] can be the complement of a preposition, although it is not possible for a preposition to take a clausal complement. Example (129d) shows that mixed coordinate structures in which the clause comes first are also unacceptable.

| a. | You can depend on my assistance. |

| b. | * | You can depend on that I will be on time. |

| c. | You can depend on my assistance and that I will be on time. |

| d. | * | You can depend on that I will be on time and my assistance. |

It is relevant to note here that all the examples of mixed coordinate structures provided by Zhang are sentence-final; this allows an analysis according to which we are dealing with an extraposed PP-complement. To see why this is relevant, we need to consider the Dutch counterparts of these examples. First, consider the Dutch (130a), which shows that complement-PPs with a nominal complement can precede or follow the verb(s) in clause-final position. The (b)-examples show that PPs with a clausal complement are marked in both positions, and that the complement-PP is usually realized instead by a clause in postverbal position preceded by the anticipatory pronominal PP eropon it in preverbal position.

| a. | Je | kan | <op mijn hulp> | rekenen <op mijn hulp>. | |

| you | can | on my assistance | count |

| b. | *? | Je | kan | <op | dat | ik | op tijd | ben> | rekenen <op dat ik op tijd ben>. |

| you | can | on | that | I | on time | am | count |

| b'. | Je | kan | erop | rekenen | [dat | ik | op tijd | ben]. | |

| you | can | on.it | count | that | I | on time | am | ||

| 'You can depend on it that I will be on time.' | |||||||||

However, we should not account for the markedness of (130b) by prohibiting that complement-PPs may contain a clausal complement, since this is at least marginally possible in topicalization constructions such as (131a). The contrast in acceptability between (130b) above and (131a) below seems to be related to the fact, illustrated in (131b), that topicalization is excluded when the anticipatory pronominal PP eropon it is present; cf. Haslinger (2007).

| a. | ? | [Op | dat | ik | op tijd | kom] | kan | je | rekenen. |

| on | that | I | on time | come | can | you | count |

| b. | * | [Dat | ik | op tijd | kom] | kan | je | erop | rekenen. |

| that | I | on time | come | can | you | on.it | count |

Now consider the Dutch counterparts of the English examples in (129c&d), which are given in (132). The acceptability of (132a) is expected, since it is consistent with the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands in (124), as well as with the earlier observation that clauses can occur as complements of PP-complements when the anticipatory pronominal PP eropon it cannot be used for some reason or other. The unacceptability of (132b) is not expected on syntactic grounds, but it may be degraded for the rather superficial reason that the P-NP sequences are more frequent than P-clause sequences and are therefore easier to parse. If English PP-complements behave in the same way as their Dutch counterparts, the acceptability pattern found in (129) is accounted for.

| a. | Je | kan | rekenen | [op | [[mijn hulp] | en | [dat | ik | op tijd | ben]]]. | |

| you | can | count | on | my help | and | that | I | on time | am | ||

| 'You can count on my help and that I'll be on time.' | |||||||||||

| b. | *? | Je | kan | rekenen | [op | [[dat | ik | op tijd | ben] | en | [mijn hulp]]]. |

| you | can | count | on | that | I | on time | am | and | my help |

Note that examples such as (133) are also fairly acceptable in Dutch. If examples of this kind are to be considered grammatical, we may be dealing with a case of “split” coordination; Subsection IIB will analyze what looks like the extraposed part of such splits as a reduced clause.

| ? | Je | kan | op mijn hulp | rekenen | en | dat | ik | op tijd | ben. | |

| you | can | on my help | count | and | that | I | on time | am | ||

| 'You can count on my help and that I'll be on time.' | ||||||||||

A similar “split” coordination analysis can also account for the other mixed examples provided by Zhang. We illustrate this for example (134a), where an object DP and an adverbial PP seem to have entered into a single coordinate structure, which would be rendered as (134b) in Dutch; we provide the clause in its embedded form in order to show that we are dealing with “split’ coordination.

| a. | He read only The Times and only on Sundays. |

| b. | dat | hij | alleen The Times | leest | en | dat | hij | alleen op zondag | leest. | |

| that | he | only The Times | reads | and | that | he | only on Sunday | reads | ||

| 'that he only reads The Times and only on Sundays.' | ||||||||||

Our tentative conclusion from this brief discussion is that the English data in Zhang has simply received an incorrect analysis and that the generalization in (124) can be maintained in full force. This conclusion is desirable, since it is fully consistent with the hypothesis found in the semantic literature that the coordinands in a coordinate structure must be of the same semantic type (cf. Section 38.1, sub IVF), since syntactic functions can be reformulated in terms of semantic types in the prototypical case. There are, however, some problems of a theory-internal nature for the semantic approach that do not arise with (124). For example, proper nouns and definite descriptions are often taken to be semantically different: while proper nouns are usually taken to be entities (type e), definite descriptions are taken to denote sets of properties (type <<e,t>,t>). If coordinands must be of the same semantic type, we need a type-changing operation in order to allow for coordinate structures such as (135c); cf. Winter (2001a). Note that we do not present this remark as an argument against the semantic approach, since this type-changing operation may be needed for independent reasons. Indeed, it is to be expected that syntactic and semantic approaches will converge on this issue.

| a. | Jan heeft | gewandeld. | type e | |

| Jan has | walked |

| b. | De honden | hebben | gewandeld. | type <<e,t>,t> | |

| the dogs | have | walked |

| c. | [[Jan] | en | [de honden]] | hebben | gewandeld. | |

| Jan | and | the dogs | have | walked |

It is important to note that generalization (124) does not claim that a coordinate structure can always be replaced by its individual coordinands, since there may be various interfering factors unrelated to coordination that may affect the acceptability of the resulting structure. One of these factors is subject-verb agreement: while the coordinate structure in (135c) above can be replaced by its second coordinand, which would result in (135b), it is not possible to replace it by its first coordinand just like that, as this would result in an agreement mismatch: *Jan hebben gewandeld. Another factor may be the semantic selection restrictions imposed by the predicate on its arguments: a verb such as zich verspreidento spread in (136) selects a plural subject, and consequently it is impossible to omit the second coordinand even if we adjust the form of the finite verb.

| a. | Jan en | zijn vrienden | verspreiden | zich. | |

| Jan and | his friends | spread | refl | ||

| 'Jan and his friends are spreading out.' | |||||

| b. | Zijn vrienden | verspreiden | zich. | |

| his friends | spread | refl | ||

| 'His friends are spreading.' | ||||

| c. | $ | Jan verspreidt | zich. |

| Jan spreads | refl |

The examples in (137) show that there are also inverse cases, i.e. cases where a coordinate structure cannot be used in a position where its coordinands are possible as independent phrases. This is related to the fact that example (137a) involves the fixed collocation een foto nemento take a picture, while een koekje nemento take a cookie is (137b) is fully compositional. The dollar sign indicates that, under the interpretation intended here, example (137c) would normally be interpreted as a linguistic pun, and regarded as marked otherwise.

| a. | Marie | nam | een foto. | |

| Marie | took | a picture |

| b. | Marie nam | een koekje. | |

| Marie took | a cookie |

| c. | $ | Marie nam | [[een foto] | en | [een koekje]]. |

| Marie took | a picture | and | a cookie |

Another idiomatic case is given in (138) with the expression de geest gevento die; the nominal expression de geest cannot be coordinated with a nominal expression functioning as a referential theme argument of gevento give; of course, the verbal expression as a whole can be coordinated with the compositional verbal projection het geld geven, as is illustrated in (138b).

| a. | * | De koning | gaf | [het geld | en | de geest]. |

| the king | gave | the money | and | the spirit |

| b. | De koning | [gaf | het geld] | en | [gaf | de geest]. | |

| the king | gave | the money | and | gave | the spirit | ||

| 'The king gave the money and died.' | |||||||

A third case, adapted from Dik (1997:200ff.), is illustrated in the examples in (139): while the simple clauses in (139a&b) are both fully acceptable, the coordinate structure in (139c) is severely degraded.

| a. | Jan zag [Marie | vallen]. | |

| Jan saw Marie | fall | ||

| 'Jan saw Marie fall.' | |||

| b. | Jan zag | [dat | Marie opstond]. | |

| Jan saw | that | Marie up-got | ||

| 'Jan saw that Marie got to her feet.' | ||||

| c. | * | Jan zag | [[Marie | vallen] | en | [dat | zij | opstond]]. |

| Jan saw | Marie | fall | and | that | she | up-got |

Dik claims that the two verbal complements are of a different semantic type and attributes the unacceptability to the selection restrictions imposed by the perception verb ziento see. Alternative accounts might appeal to the fact that the infinitival construction in (139a) has certain special syntactic properties that the construction in (139b) lacks: for instance, the subject of the infinitival clause depends on the perception verb zien for case assignment and the verbal head of the infinitival clause and the perception verb form a verb cluster; cf. the discussion of perception verbs in Section V5.2.3.3. It is not so easy to choose between the available options: an appeal to selection restrictions would predict that examples such as (140) are unacceptable, while e.g. the verb-cluster approach would predict that such examples are possible. However, examples like those in (140) seem to have an intermediate status; they are marked but certainly less degraded than example (139c).

| a. | ?? | Jan heeft | me | beloofd | [[dat hij komt] | en | [om | te blijven | eten]]. |

| Jan has | me | promised | that he comes | and | comp | to stay | eat | ||

| Compare: 'Jan promised me that he will come and to stay for dinner.' | |||||||||

| b. | ? | Jan heeft | me | beloofd | [[om | te komen] | en | [dat | hij | blijft | eten]]. |

| Jan has | me | promised | comp | to come | and | that | he | stays | eat | ||

| Compare: 'Jan promised me to come and that he will stay for dinner.' | |||||||||||

Whatever the correct analysis of the degraded status of (139c), this case also illustrates that the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands in (124) do not imply that a coordinate structure can always be used in a position where its coordinands are possible as independent phrases, since there may be interfering factors unrelated to coordination that may affect the acceptability of the resulting structure.

A final case worth mentioning is illustrated in (141). These examples show that the selection restrictions imposed by the predicative coordinands on their subjects must be similar; while the individual-level predicate zijn zoogdieren triggers a generic reading on the bare plural subject, the stage-level predicate op dit moment buiten blaffen triggers an indefinite reading. The examples in (142) show that we find essentially the same for the singular noun phrase een honda dog.

| a. | Honden | zijn | zoogdieren. | generic subject | |

| dogs | are | mammals |

| b. | Er | blaffen | op dit moment honden | buiten. | indefinite subject | |

| there | bark | at this moment dogs | outside | |||

| 'Dogs are barking outside at this moment.' | ||||||

| c. | * | Honden | [[zijn | zoogdieren] | en | [blaffen | op dit moment | buiten]]. |

| dogs | are | mammals | and | bark | at this moment | outside |

| a. | Een hond | is een zoogdier. | generic subject | |

| a dog | is a mammal |

| b. | Er | blaft | op dit moment | een hond | buiten. | indefinite subject | |

| there | barks | at this moment | a dog | outside | |||

| 'A dog is barking outside at this moment.' | |||||||

| c. | * | Een hond | [[is | een zoogdier] | en | [blaft | op dit moment | buiten]]. |

| a dog | is | a mammal | and | barks | at this moment | outside |

As far as Dutch is concerned, one might ask whether it is really necessary to assume that coordinated predicates must impose similar selection restrictions on their subject, given that generic and indefinite subjects clearly occupy different positions in the (a)- and (b)-examples: the co-occurrence restriction on coordinands in (116) is thus sufficient to exclude the (c)-examples. Furthermore, the examples in (143) show that predicates selecting a cumulative and a distributive subject, respectively, can be coordinated.

| a. | De jongens | ruimden | samen | de troep | op. | cumulative subject | |

| the boys | cleared | together | the mess | up | |||

| 'The boys cleared up the mess together.' | |||||||

| b. | De jongens | kregen | elk | 10 Euro. | distributive subject | |

| the boys | got | elk | 10 Euro | |||

| 'The boys got 10 Euro each.' | ||||||

| c. | De jongen | [[ruimden | samen | de troep | op] | en | [kregen | elk | 10 Euro]]. | |

| the boys | cleared | together | the mess | up | and | got | each | 10 Euro | ||

| 'The boys tidied up the mess together and received 10 Euros each.' | ||||||||||

Since the English renderings of (141c) and (142c) are also unacceptable (cf. Zhang 2010:188), despite the fact that the generic and indefinite subjects seem to occupy the same position, this may suggest that we are minimally dealing with a restriction on the semantic type of predicative coordinands: “mixed” cases of individual and stage-level predicates cannot be coordinated.

The previous subsections have shown that coordinate structures must satisfy the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands in (144). We have found only a limited number of remarks on restrictions concerning the semantic nature of the coordinands in the literature we have consulted; more research seems to be needed to determine whether any finer distinctions go beyond the individual and stage-level distinction. We have not extensively discussed the hypothesis found in the semantic literature that the coordinands should be of the same semantic type (entity, predicate, etc.), because this hypothesis is more or less equivalent to the first part of restriction (144a); see Subsection B for a brief discussion of this.

| Co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands (final version): |

| a. | Coordinands in a coordinate structure are of the same syntactic type: they can have the same syntactic functions and may occur in the same syntactic positions as the coordinate structure as a whole. |

| b. | Predicative coordinands are of the same semantic type, i.e. individual-level or stage-level. |

It should be noted that there are a number of co-occurrence restrictions that are not (immediately) related to those given in (144). Given the difference in the syntactic function of the two PPs in (145a), it follows directly from (144a) that the coordinate structure in (145b) is impossible (on the intended interpretation), but it may not be immediately clear why (145c) is also unacceptable, since this is only indirectly related to syntactic function; here the PP cannot be interpreted as an argument and a place adverbial at the same time.

| a. | Jan wacht | op Peter/op het perron. | complement/place adverbial | |

| Jan waits | for Peter/on the platform | |||

| 'Jan is waiting for Peter/on the platform.' | ||||

| b. | * | Jan wacht | [[op Peter] | en | [op het perron]]. |

| Jan waits | for Peter | and | on the platform |

| c. | * | Jan wacht | [op | [Peter | en | het perron]]. |

| Jan waits | op | Peter | and | the platform |

The (c)-examples in (146) and (147) show that coordination is sometimes also sensitive to the thematic role of the coordinands: while the coordinands can all be used as subjects they cannot be coordinated due to the fact that they have different semantic roles: agent versus instrument/means.

| a. | Janagent | opende | de deur | (met de sleutelinstrument). | |

| Jan | opened | the door | with the key |

| b. | De sleutelinstrument | opende | de deur. | |

| the key | opened | the door |

| c. | * | [Janagent | en | de sleutelinstrument] | openden | de deur. |

| Jan | and | the key | opened | the door |

| a. | Janagent | vulde | het gat | (met het zandmeans). | |

| Jan | filled | the hole | with the sand |

| b. | Het zandmeans | vulde | het gat. | |

| the sand | filled | the hole |

| c. | * | [Janagent | en | het zandmeans] | vulden | het gat. |

| Jan | and | the sand | filled | the hole |

Although this does not seem to follow from (144a) at first sight, it can be derived from it in a straightforward way. While Section V9.5 has argued that agents (i.e. the external argument of V) are arguably base-generated in the highest specifier of the lexical part of the verbal projection (vP), it seems plausible that instruments/means are generated in some other position (e.g. corresponding to that of the met-PP); if this is indeed the case, the unacceptability of the (c)-examples follows from (144a) on the plausible (and often tacitly adopted) assumption that coordinate structures are formed before they are inserted into some larger syntactic structure.

This subsection discusses the restrictions on movement out of coordinate structures that have come to be known as the coordinate structure constraint. In particular, we will address the question of whether or not these restrictions should be accounted for by appealing to independently established locality conditions on movement. Since the coordinate structure constraint can be violated when movement is applied in a so-called across-the-board fashion, we will conclude that this is not possible, and that the valid part of the coordinate structure constraint should instead be accounted for in terms of the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands in (124) from Subsection I.

Coordinate structures exhibit island effects in the sense that it is usually not possible to extract a constituent from them. This generalization is known as the coordinate structure constraint; the version in (148) is adapted from Ross (1967 (4.84)).

| Coordinate structure constraint: | ||

| Extraction from a coordinate structure is impossible: neither the coordinands themselves nor any phrase contained in them can be extracted from the coordinate structure by movement. |

The two instances mentioned in (148) are illustrated in (149) by wh-movement of (a part of) a direct object: while (149a) shows that it is possible to wh-move an object as a whole, the (b)-examples in (149) show that it is not possible to wh-move the first (or second) coordinand of a coordinate structure functioning as a direct object, and the (c)-examples show that it is not possible to wh-move an object if the verbal projection including it functions as a coordinand in a coordinate structure.

| a. | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan ti | gelezen? | |

| which book | has | Jan | read |

| b. | Jan heeft | [jouw boek | en | haar artikel] | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | your book | and | her article | read | ||

| 'Jan has read your book and her article.' | ||||||

| b'. | * | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan [ti | en | haar artikel] | gelezen? |

| which book | has | Jan | and | her article | read |

| b''. | * | Welk artikeli | heeft | Jan | [jouw boek | en ti] | gelezen? |

| which article | has | Jan | your book | and | read |

| c. | Jan heeft | [[jouw boek | gelezen] | en | [haar artikel | bestudeerd]]. | |

| Jan has | your book | read | and | her article | studied | ||

| 'Jan has read your book and studied her article.' | |||||||

| c'. | * | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan [[ti | gelezen] | en | [haar artikel | bestudeerd]]? |

| which book | has | Jan | read | and | her article | studied |

| c''. | * | Welk artikeli | heeft | Jan | [[jouw boek | gelezen] | en [ti | bestudeerd]]? |

| which article | has | Jan | your book | read | and | studied |

Note in passing that the primed examples are also unacceptable when the wh-phrase remains in situ, as is clear from the fact that example (150a), in which the coordinate structure remains in its base position, and example (150b), in which the coordinate structure is wh-moved into the clause-initial position, are both unacceptable. This shows that coordination of interrogative and non-interrogative phrases is always unacceptable unless we are dealing with an echo-interpretation: cf. Jan heeft jouw boek en wat\`1welk artikel gelezen? Jan has read your book and what/which article?.

| a. | * | Jan heeft | [jouw boek | en | welk artikel] | gelezen? |

| Jan has | your book | and | her article | read |

| b. | * | [Jouw boek | en | welk artikel] | heeft | Jan | gelezen? |

| your book | and | which article | has | Jan | read |

A possible counterexample to the coordinate structure constraint in (148) is given in (151), which suggests that in some cases it is possible to split coordinate structures by placing the coordinator and the following coordinand (henceforth: [en/of/maar XP]) after the verbs in clause-final position. Note that some speakers prefer to repeat the preposition metwith in examples such as (151b') and that this actually applies more generally to adverbial phrases of e.g. place and time: cf. ze hebben na het ontbijt gewandeld en ??(na) het avondeten They walked after breakfast and after dinner.

| a. | dat | ik | Marie en Jan | gisteren | ontmoette. | |

| that | I | Marie and Jan | yesterday | met | ||

| 'that I met and Jan Marie yesterday' | ||||||

| a'. | dat | ik | Marie gisteren | ontmoette, | en Jan. | |

| that | I | Marie yesterday | met | and Jan |

| b. | dat | de directeur | met zijn vader of zijn moeder | gesproken | heeft. | |

| that | the principal | with his father or his mother | spoken | has | ||

| 'that the principal has spoken with his father or mother.' | ||||||

| b'. | dat | de directeur | met zijn vader | gesproken | heeft, | of zijn moeder. | |

| that | the principal | with his father | spoken | has | or his mother |

| c. | dat | deze leraar | erg streng | maar | geliefd | is. | |

| that | this teacher | very strict | but | popular | is | ||

| 'that this teacher is very strict but popular.' | |||||||

| c'. | dat | deze leraar | erg streng | is, | maar | geliefd. | |

| that | this teacher | very strict | is | but | popular |

The coordinate structure constraint predicts that the split pattern cannot be derived by movement and the following two subsections will show that there are indeed independent reasons for assuming that a movement approach is not viable. We will therefore argue in favor of an ellipsis approach, i.e. that we are dealing here with clausal coordinands with ellipsis in the second coordinand: example (151a'), for instance, is assigned the structure [[dat ik gisteren Marie ontmoette] en [dat ik gisteren Jan ontmoette]], in which strikethrough indicates non-pronunciation.

One might want to relate the primed and primeless examples in (151) to each other by movement. The first logically possible option would be to assume that the coordinate structure is base-generated to the right of the clause-final verb(s), and that the split pattern in the primed examples is derived from the same structure underlying the primeless examples by leftward movement of the first coordinand into preverbal position; cf. Johannessen (1998:§6.2). A serious problem for this approach would be that the [en/of/maar XP] remnants in (151) appear in a position that normally does not allow for a direct object or a complementive, as shown in (152).

| a. | * | dat | ik | gisteren | ontmoette | Jan. |

| that | I | yesterday | met | Jan |

| b. | * | dat | deze leraar | is geliefd. |

| that | this teacher | is popular |

The second logically possible option would be to assume that the coordinate structure is base-generated to the left of the clause-final verb(s) and that the string [en/of/maar XP] is extraposed while stranding the first coordinand; cf. Munn (1993:15). This proposal faces the problem that the presumed movement can only be rightward: deriving the topicalization structures in (153) from the primeless examples in (151) leads to unacceptable and indeed uninterpretable results; see also Zhang (2010:§2.3.2), and the references cited there.

| a. | * | En | Jan ontmoette | ik | Marie gisteren. |

| and | Jan met | I | Marie yesterday |

| b. | * | Of zijn moeder | heeft | de directeur | met zijn vader | gesproken. |

| or his mother | has | the principal | with his father | spoken |

| c. | * | Maar | geliefd | is deze leraar | erg streng. |

| but | popular | is this teacher | very strict |

The extraposition approach also runs into several other problems with coordinate structures functioning as subjects (which, in fact, would probably also carry over to the first option under standard assumptions about agreement). First, if (154b) is derived from the same underlying structure as (154a), it remains unclear why the two structures differ in subject-verb agreement; cf. Neijt (1979) and De Vries & Herringa (2008).

| a. | dat | Marie en Jan | morgen | op visite | komen/*komt. | |

| that | Marie and Jan | tomorrow | on visit | come/comes | ||

| 'that Marie and Jan will visit us tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Marie | morgen | op visite | komt/*komen, | en Jan. | |

| that | Marie | tomorrow | on visit | comes/come | and Jan |

Second, if (155b) were derived from the same underlying structure as (155a), it is also unclear why the reciprocal elkaareach other cannot be licensed in (155b), since the supposed underlying form of both examples satisfies the condition that the reciprocal has a plural antecedent.

| a. | dat | Els en Marie | met elkaar | discussiëren. | |

| that | Els and Marie | with each.other | discuss | ||

| 'that Els and Marie are arguing with each other.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Els (*met elkaar) | discussieert, | en Marie. | |

| that | Els with each.other | discusses | and Marie |

A third problem is raised by examples such as (156) with a collective verbal expression such as ruzie hebbento argue; while (156b) unambiguously expresses that both the boys and the girls are arguing, example (156a) is ambiguous in that it can also express that the boys are arguing with the girls. This difference in meaning again suggests that the two examples do not have the same underlying structure.

| a. | dat | de jongens en de meisjes | ruzie | hebben. | |

| that | the boys and the girls | an.argument | have | ||

| 'that the boys and the girls are having an argument.' | |||||

| b. | dat | de jongens | ruzie | hebben, | en de meisjes. | |

| that | the buys | an.argument | have | and the girls | ||

| 'that the boys are having an argument, and the girls.' | ||||||

A fourth potential problem for a movement analysis is that “split” coordination is incompatible with the adverbial modifiers samentogether and beidenboth, which disambiguate example (157a) with respect to the distributive/cumulative dichotomy. This again suggests that the two examples do not have the same underlying structure.

| a. | Els en Marie | hebben | samen/beiden | de rots | opgetild. | |

| Els and Marie | have | together/both | the rock | prt.-lifted | ||

| 'Els and Marie have both lifted the rock/lifted the rock together.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Els heeft | samen/beiden | de rots | opgetild, | en Marie. |

| Els has | together/both | the rock | prt.-lifted | and Marie |

In fact, the examples in (158) show that split coordination is incompatible with the cumulative reading: while example (158a) allows the reading that Els and Marie are collaborators, (158b) does not.

| a. | dat | Els en Marie | een goed team | vormen. | |

| that | Els and Marie | a good team | constitute | ||

| 'that Els and Marie make a good team.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Els een goed team | #vormt/*vormen, | en Marie. | |

| that | Els a good team | constitutes/constitute | and Marie |

The two previous subsections have shown that split coordination cannot be derived by movement and thus does not constitute a counterexample to the coordinate structure constraint in (148). The conclusion must be that split coordination is base-generated: we are dealing with a construction in which a clause functions as the first coordinand: [clause en/of/maar XP]. The split and the unsplit variant thus have structures of the kind given in (159).

| a. | dat | ik | gisteren | [Marie en Jan] | gesproken | heb. | unsplit | |

| that | I | yesterday | Marie and Jan | spoken | have | |||

| 'that I talked with Marie and Jan yesterday.' | ||||||||

| b. | [[dat | ik | gisteren | Marie gesproken | heb] | en | [Jan]]. | split | |

| that | I | yesterday | Marie spoken | have | and | Jan | |||

| 'that I talked with Marie yesterday, and Jan.' | |||||||||

One argument in favor of the base-generation approach can be based on the acceptability contrast found in (160). First, it is unclear how the movement approaches discussed earlier can account for the acceptability contrast between these two examples: why should leftward movement be restricted to a single coordinand, and why should rightward movement of the [en XP] sequence be allowed from a dyadic but not from a polyadic coordinate structure? Second, the acceptability contrast in (160) follows straightforwardly under the base-generation account, since the first clausal coordinand in (160b) simply violates the distributional restriction on asyndetic coordinate structures that they cannot occur as clausal constituents. That this is the case is clear from the fact that the clause is also unacceptable without the “postverbal” [en XP] sequence: cf. *dat ik gisteren Els, Marie gesproken heb.

| a. | dat | ik | gisteren | Els, Marie en Jan | gesproken | heb | |

| that | I | yesterday | Els, Marie and Jan | spoken | have | ||

| 'that I talked with Els, Marie and Jan yesterday.' | |||||||

| b. | * | [[dat | ik | gisteren | Els, Marie | gesproken | heb] | en | [Jan]]. |

| that | I | yesterday | Els, Marie | spoken | have | and | Jan |

Moreover, the data from the previous subsection on the extraposition approach receive a natural account in the base-generation approach: the examples in (161) are simply unacceptable because the clauses constituting the first coordinand are unacceptable on their own: the clause in (161a) exhibits the wrong subject-verb agreement, the clause in (161b) does not contain a proper antecedent for the reciprocal elkaar, and the clauses in (161c&d) have no subject suitable for licensing the adverbial modifiers or for satisfying the selection restriction of the verb vormen (in its the intended sense of “to constitute”); see also Chaves (2012:fn.2) and De Vries (2017:fn.6).

| a. | * | [[dat | Marie | morgen | op visite | komen], | en | [Jan]]. | agreement |

| that | Marie | tomorrow | on visit | comes | and | Jan |

| b. | * | [[dat | Els | met elkaar | discussieert], | en [Marie]]. | reciprocal |

| that | Els | with each.other | discusses | and Marie |

| c. | * | [[Els | heeft | samen/beiden | de rots | opgetild], | en | [Marie]]. | modifiers |

| Els | has | together/both | the rock | prt.-lifted | and | Marie |

| d. | # | [[dat | Els een goed team | vormt], | en [Marie]]. | selection |

| that | Els a good team | constitutes | and Marie |

If split coordinate structures are indeed of the form [clause en/of/maar XP], then the question should arise as to what XP is. Since the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands discussed in Subsection I require that the coordinands following en are clauses (or perhaps some smaller verbal projections), we would like to propose that XP is an ellipsis remnant of these clausal coordinands; we are dealing with clausal coordination [[clause W XP Z] en/of/maar [clause W YP Z]], in which the strings W and Z in the second clause are elided under identity with the same strings in the first clause. In fact, this revives Cremer’s (1993:§2.5.1) conclusion that examples such as (162b) must be biclausal because they must be construed as referring to two separate events. Recall that an example such as (162a) is ambiguous in this respect: it refers to two separate events if the conjunction Jan en Peter is interpreted distributively but to a single event if it is interpreted cumulatively.

| a. | Marie heeft | daarna | Jan en Peter | opgebeld. | one or two events | |

| Marie has | aftter.that | Jan and Peter | prt.-called | |||

| 'Marie phoned Jan and Peter after that.' | ||||||

| b. | Marie heeft | daarna | Jan opgebeld, | en Peter. | two events | |

| Marie has | aftter.that | Jan prt.-called | and Peter | |||

| 'Marie phoned Jan and Peter after that.' | ||||||

Evidence for the ellipsis approach can also be provided by so-called specifying coordination constructions such as given in (163); cf. Kraak & Klooster (1972:259). Examples like these are special in that the coordinator enand does not have its prototypical meaning contribution: (163a) does not express that Jan has bought a dog and a poodle (two separate entities), but that he has bought a dog, which is a poodle (one entity); and (163b) does not express that Jan went downstairs and into the cellar (two separate events), but that he went downstairs, i.e. into the cellar (one event). In short, the [en wel XP] phrases provide a specification of the denotation of some previously mentioned phrase.

| a. | Jan | heeft | een hond | gekocht, | en | wel | een poedel. | |

| Jan | has | a dog | bought | and | prt | a poodle | ||

| 'I have bought a dog, a poodle.' | ||||||||

| b. | Jan is naar beneden | gegaan, | en | wel | naar de kelder. | |

| Jan is to downstairs | gone | and | prt | to the cellar | ||

| 'Jan has gone downstairs, to the cellar.' | ||||||

Kraak & Klooster suggest that the examples in (163) are of a similar kind to those in (164), where [en wel XP] provides a further specification of the denotation of the VP in the preceding clause. The crucial point here is that the [en wel XP] phrases in (164) are clearly not base-generated as part of a coordinate structure embedded in the clause, since the clauses do not contain any constituent that could function as the first coordinand of such a putative coordinate structure.

| a. | De jongens | zijn | vertrokken, | en | (wel) | vroeg. | |

| the boys | are | left, | and | prt | early | ||

| 'The boys have left, early.' | |||||||

| b. | De jongens | zijn | aan het | dansen, | en | wel | met elkaar. | |

| the boys | are | aan het | dance | and | prt | with each.other | ||

| 'The boys are dancing, with each other.' | ||||||||

For this reason, the co-occurrence restrictions on coordinands in (124) imply that the phrases following en are reduced clauses (or some smaller verbal projections) and that the structures of (163a) and (164a) should therefore be as indicated in (165); cf. De Vries (2006/2009). Note in passing that we have placed the particle wel in a position external to the second coordinand for convenience but that this requires more argumentation and may well be wrong.

| a. | [[Ik | heb | een hond | gekocht] | en | wel | [ik heb | een poedel | gekocht]]. | |

| I | have | a dog | bought | and | prt | I have | a poodle | bought |

| b. | [[De jongens | zijn vertrokken] | en | wel | [de jongens | zijn | vroeg | vertrokken]]. | |

| the boys | are left, | and | prt | the boys | are | early | left |

The analysis in (165) also accounts for the fact that the [en wel XP] phrases cannot easily be placed in preverbal position. The (a)-examples in (166) show that this is relatively acceptable in examples like those in (163), but only when [en XP] is parenthetical, i.e. preceded and followed by an intonation break. The (b)-examples in (166) show that this is straightforwardly impossible for the examples in (164); these are acceptable only if the coordinator is dropped.

| a. | (?) | Ik | heb | een hond | –en | wel | een poedel– | gekocht. |

| I | have | a dog | and | prt | a poodle | bought |

| a'. | (?) | Jan is naar beneden | –en | wel | naar de kelder– | gegaan. |

| Jan is to downstairs | and | prt | to the cellar. | gone |

| b. | De jongens | zijn | (*en | wel) | vroeg | vertrokken. | |

| the boy | are | and | prt | early | left |

| b'. | De jongens | zijn | (*en | wel) | met elkaar | aan het | dansen. | |

| the boys | are | and | prt | with each.other | aan het | dance |

If we are indeed dealing with reduced clauses in split coordination constructions, the phonetic reduction may be of that found in the gapping constructions discussed in Section 39.2 and/or the fragment clauses discussed in Section V5.1; see Johannessen (1998:§6.3.2), Schwarz (1999), and Zhang (2010:§2.3.2), and the references cited there. We will return to this issue in Section 39.2, and provisionally conclude for the moment that apparent cases of “split” coordination cannot be used to refute the coordinate structure constraint in (148).

It has been claimed that in certain forms of so-called asymmetric coordination it is possible to violate the part of the coordinate structure constraint that prohibits extraction of a phrase from a single coordinand. A prototypical case for English is given in (167b), which apparently allows wh-movement from the second (but not from the first) coordinand.

| a. | John [[went to the store] and [bought some ice cream]]. |

| b. | Whati did John [[go to the store] and [buy ti]]? |

Example (168b) shows that similar examples are definitely impossible in Dutch. This strongly suggests that Ross (1967:§4.2.3) and Schmerling (1975) are correct in arguing that the examples in (167) are cases of “fake” coordination, although this has remained a topic of debate; we refer the reader to Zhang (2010:§5.3) for a concise review and references.

| a. | Jan heeft | [[het museum bezocht] | en | [een mooi schilderij | gezien]]. | |

| Jan has | the museum visited | and | a beautiful painting | seen |

| b. | * | Wati | heeft | Jan | [[het museum | bezocht] | en [ti | gezien]]. |

| what | has | Jan | the museum | visited | and | seen |

| b'. | * | Wati | heeft | Jan [[ti | bezocht] | en | [een mooi schilderij | gezien]]. |

| what | has | Jan | visited | and | beautiful painting | seen |

Section 38.4.1, sub IC, will show, however, that there are several other types of asymmetric coordination in Dutch which express a special semantic (causal, concessive, etc.) relation between the first and the second coordinand. Van der Heijden (1999:65) has claimed that some of these cases also allow extraction of a phrase from a single coordinand. An example (adapted from her work) is (169b); the percent sign in (169b) is used to indicate that some speakers (including ourselves) do not find this example acceptable.

| a. | Jan kan | 50 eieren | eten | en | toch | niet | ziek | worden. | |

| Jan is.able | 50 eggs | eat | and | prt | not | ill | become | ||

| 'Jan can eat 50 eggs without getting ill.' | |||||||||

| b. | % | Hoeveel eiereni | kan | je ti | eten | en | toch | niet | ziek | worden? |

| how many eggs | can | one | eat | and | still | not | sick | get | ||

| 'How many eggs can one eat without getting ill?' | ||||||||||

It is not obvious that examples such as (169b) should be taken as counterexamples to the coordinate structure constraint, because their internal structure is not clear. First, the presupposition that we are dealing with some kind of VP-coordination is problematic, because it does not seem to be possible to construe the root (deontic) modal kunnento be able in the examples in (169) with the second coordinand, as is clear from the fact that the modal verb in (170a) preferably receives an epistemic reading. Second, De Vries (2005) notes that extraction is only possible from the first coordinand: the fact that examples such as (170b) cannot be derived from (169a) would be surprising if the coordinate structure constraint did not apply to asymmetric coordinate structures.

| a. | Jan/Je | kan | daardoor | toch | niet | ziek | worden. | |

| Jan/one | can | by that | prt | not | ill | become | ||

| 'Jan/One cannot get ill because of that.' | ||||||||

| b. | * | Wati | kan | Jan | 50 eieren | eten | en | toch | niet ti | worden? |

| what | can | Jan | 50 eggs | eat | and | still | not | become | ||

| Literally: 'What can Jan eat 50 eggs and still not become?' | ||||||||||

De Vries (2005) suggests a third type of possible counterexample, which is based on a construction known in the Dutch literature as balansschikking, which will be discussed in more detail in Section 38.4.1, sub IID. Consider example (171a), in which the first coordinand modifies the second conjunct in the way indicated by the English translation. De Vries takes the controversial, but possibly correct, position that we are dealing with normal disjunction and claims that wh-extraction from the first coordinand is acceptable. For the sake of the argument, we will assume that (171b) is grammatical although some informants (including ourselves) reject such examples, as is indicated by the percent sign.

| a. | Jan had | het boek | nog | niet | gekregen | of | hij | gaf | het | weg. | |

| Jan had | the book | yet | not | received | or | he | gave | it | away | ||

| 'Jan gave away the book immediately after he received it.' | |||||||||||

| b. | % | Wati | had Jan | nog | niet ti | ontvangen | of | hij | gaf | het | weg? |

| what | had Jan | yet | not | received | or | he | gave | it | away | ||

| Intended: 'What did Jan give away immediately after he received it?' | |||||||||||

It should be noted, however, that example (171b) is not a counterexample to the coordinate structure constraint because we are dealing with coordination of two main clauses and wh-movement targets the first position of the first main clause. Or, to put it differently, we are dealing with a disjunction of an interrogative and a declarative main clause (which may be the reason why some informants reject this example; cf. Section 38.4.1, sub IIA). The structure of (171b) is thus as given in (172), which does not violate the coordinate structure constraint.

| [[Wati | had Jan | nog | niet ti | ontvangen] | of | [hij | gaf | het | weg]]? | ||

| what | had Jan | yet | not | received | or | he | gave | it | away | ||

| 'What did Jan give away immediately after he received it?' | |||||||||||

This analysis also accounts for the fact noted by De Vries that a similar “extraction” from the second coordinand is impossible: the only way to derive *Wati was Jan nog niet thuis of hij gaf Marie ti from (173a) is by moving the wh-object of the second clausal coordinand clause into the initial position of the first clausal coordinand, which is not allowed for independent reasons.

| a. | [Clause | Jan was nog niet | thuis] | of [Clause | hij gaf Marie het boek]. | |

| [Clause | Jan was yet not | home | or | he gave Marie the book | ||

| 'Jan gave Marie the book immediately after he came home.' | ||||||

| b. | * | [Clause | Wati | was Jan nog niet | thuis] | of [Clause | hij gaf Marie ti ]. |

| * | [Clause | what | was Jan yet not | home | or | he gave Marie |

This subsection has discussed some possible violations of the coordinate structure constraint involving asymmetric coordination. The first case can only be demonstrated for English, and it has been argued that it involves “fake” coordination. The second case can be found in both English and Dutch (although not all Dutch speakers accept it), but it is unclear whether it is really run-of-the-mill coordination. The third case (also rejected by some speakers) is found in so-called balansschikking constructions, but has been shown to be irrelevant, since it seems to be based on the false assumption that the movement targets a position external to the first coordinand. We therefore conclude that wh-movement in asymmetric coordination does not provide conclusive evidence against the coordinate structure constraint.

A well-known exception to the coordinate structure constraint is so-called across-the-board movement: extraction from a coordinate structure is possible if the movement is applied in such as a way that it affects the same type of constituent in all coordinands. A characteristic example is given in (174a), where the wh-phrase welk boekwhich book is related to the two interpretative gaps indicated by ti, which function as the direct object of the first and the second coordinand, respectively. The (b)-examples give the corresponding examples in which the movement is not applied in an across-the-board fashion for comparison. Detailed discussions of across-the-board movement can be found in Ross (1967), Williams (1978), and De Vries (2017), and the references cited therein.

| a. | Welk boeki | heeft | [[Jan ti | gelezen] | en | [Els ti | bestudeerd]]? | |

| which book | has | Jan | read | and | Els | studied | ||

| 'Which book has Jan read and Els studied?' | ||||||||

| b. | * | Welk boeki | heeft | [[Jan ti | gelezen] | en | [Els het artikel | bestudeerd]]? |

| which book | has | Jan | read | and | Els the article | studied |

| b'. | * | Welk boeki | heeft | [[Jan het artikel | gelezen] | en | [Els ti | bestudeerd]]? |

| which book | has | Jan the article | read | and | Els | studied |

Note that across-the-board movement of the full coordinands themselves, as in (175b), is not possible. However, this should not be seen as an exception to across-the-board movement, since it may be due to the independently established fact that the coordinands in a coordinate structure cannot be identical in the prototypical case; examples such as (175a) are impossible if the two proper nouns refer to the same person. The unacceptability of (175b) is thus related to the fact that the answer to this question will provide a noun phase identifying a unique girl, which also functions as the “filler” of the two interpretative gaps, so that providing the answer Marie will result in a representation similar to the one assigned to (175a).

| a. | $ | Ik | heb | gisteren | [Marie en Marie] | bezocht. |

| I | have | yesterday | Marie and Marie | visited | ||

| 'I visited Marie and Marie yesterday.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Welk meisjei | heb | jij | gisteren [ti | en ti] | bezocht. |

| which girl | have | you | yesterday | and | visited |

This account of the unacceptability of (175b) is supported by the fact that question (174a) presupposes that there is a unique book that was read by Jan and studied by Els. It should be noted, however, that De Vries (2017) claims that the presupposition of uniqueness need not always be present in the case of across-the-board movement. This is especially true for examples such as (176), where the moved phrase contains an anaphor like zichzelfhim/herself. Speakers who accept such examples require a so-called sloppy reading of the reflexive zichzelf: zichzelf is construed as co-referential with Jan and Marie, respectively. Since the acceptability judgments on examples such as (176) are not very clear and seem to vary from speaker to speaker, we will not discuss them any further.

| % | [Welk schilderij | van zichzelf<j resp k>]i | heeft | [[Janj ti | gekocht] | en | [Mariek tj | geschilderd]]? | |

| which picture | of refl | has | Jan | bought | and | Marie | painted |

The following subsections will examine across-the-board movement in greater detail but first it should be noted that this type of movement is not restricted to coordinate structures with two coordinands. The examples used for illustration will generally involve coordinate structures with two coordinands for reasons of simplicity, but the reader should keep in mind that across-the-board movement can also apply to coordinate structures with three (or more) coordinands; we illustrate this in example (177).

| a. | Welk boeki | heeft | [[Jan ti | gelezen] | en | [Els ti | bestudeerd]]? | |

| which book | has | Jan | read | and | Els | studied | ||

| 'Which book has Jan read and Els studied?' | ||||||||

| b. | Welk boeki | heeft | [[Jan ti | gelezen], | [Els ti | bestudeerd], | [Peter ti | geannoteerd] | en | [Marie ti | samengevat]]? | |||||

| which book | has | Jan | read | Els | studied | Peter | annotated | and | Marie | summarized | ||||||

| 'Which book has Jan read, Els studied, Peter annotated, and Marie summarized?' | ||||||||||||||||

We will follow the general practice of restricting our attention mainly to conjunctions with enand: again, the reader should keep in mind that across-the-board movement is also possible in disjunctions with ofor and in adversative conjunctions with maarbut; this is illustrated in (178).

| a. | [Over ATB]i kan | [[ik | een lezing ti | geven] | of | [Jan een artikel ti | schrijven]]. | |

| about ATB can | I | a talk | give | or | Jan an article | write | ||

| 'I can give a talk on ATB, or Jan can write an article about it.' | ||||||||

| a'. | Daari kan | [[ik een lezing over ti | geven] | of | [Jan een artikel over ti | schrijven]]. | |

| there can | I a talk about | give | or | Jan an article about | write | ||

| 'I can give a talk about that or Jan can write an article about it.' | |||||||