- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Coordination and Ellipsis

- Nouns and noun phrases (JANUARI 2025)

- 15 Characterization and classification

- 16 Projection of noun phrases I: Complementation

- 16.0. Introduction

- 16.1. General observations

- 16.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 16.3. Clausal complements

- 16.4. Bibliographical notes

- 17 Projection of noun phrases II: Modification

- 17.0. Introduction

- 17.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 17.2. Premodification

- 17.3. Postmodification

- 17.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 17.3.2. Relative clauses

- 17.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 17.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 17.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 17.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 17.4. Bibliographical notes

- 18 Projection of noun phrases III: Binominal constructions

- 18.0. Introduction

- 18.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 18.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 18.3. Bibliographical notes

- 19 Determiners: Articles and pronouns

- 19.0. Introduction

- 19.1. Articles

- 19.2. Pronouns

- 19.3. Bibliographical notes

- 20 Numerals and quantifiers

- 20.0. Introduction

- 20.1. Numerals

- 20.2. Quantifiers

- 20.2.1. Introduction

- 20.2.2. Universal quantifiers: ieder/elk ‘every’ and alle ‘all’

- 20.2.3. Existential quantifiers: sommige ‘some’ and enkele ‘some’

- 20.2.4. Degree quantifiers: veel ‘many/much’ and weinig ‘few/little’

- 20.2.5. Modification of quantifiers

- 20.2.6. A note on the adverbial use of degree quantifiers

- 20.3. Quantitative er constructions

- 20.4. Partitive and pseudo-partitive constructions

- 20.5. Bibliographical notes

- 21 Predeterminers

- 21.0. Introduction

- 21.1. The universal quantifier al ‘all’ and its alternants

- 21.2. The predeterminer heel ‘all/whole’

- 21.3. A note on focus particles

- 21.4. Bibliographical notes

- 22 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- 23 Referential dependencies (binding)

- Syntax

-

- General

This section discusses the overall internal structure of the noun phrase. We will distinguish two syntactic domains. The first domain, called the NP-domain, is headed by the noun. The second domain is the DP, which is often assumed to be headed by a determiner, quantifier or numeral. We will discuss these two domains in Sections I and II, respectively. Subsection III provides a brief discussion of non-restrictive modifiers of the noun phrase. Subsection IV concludes with some remarks on word order restrictions within the noun phrase.

The NP-domain consists of the head noun as well as its complements and its restrictive modifiers (if any). The head noun is usually obligatory, except in very specific contexts where noun ellipsis is allowed; cf. Section A28.4. Details aside, the structure of the NP is usually assumed to be as indicated in (4a). Complements normally occur right-adjacent to the noun in the form of a PP or a clause (unless the noun is a nominal infinitive, which allows its complement(s) in prenominal position); an example with a PP-complement is given in (4b). Restrictive modifiers can be either pre or postnominal; prenominal modifiers are usually attributively used adjectives, as in (4c); postnominal modifiers are typically in the form of a PP, as in (4d), or a relative clause. Postnominal modifiers follow the complement of the noun in the unmarked case, which will be one reason for assuming that NPs are internally structured: modifiers are external to the phrase containing the noun and its complement(s) and so cannot appear between them (unless there is reason to assume that the complement has moved).

| a. | [NP AP [N PPCompl]] |

| b. | de [NP | [vernietiging | [van Rome]Compl]] | |

| the | destruction | of Rome |

| c. | de [NP | totaleMod | [vernietiging | [van Rome]Compl]]] | |

| the | total | destruction | of Rome |

| d. | de [NP | [vernietiging | [van Rome]Compl] | [in 410 AD]Mod] | |

| the | destruction | of Rome | in 410 AD |

For our present purposes, this brief introduction to the internal structure of the NP will suffice. A full discussion of complementation of the noun can be found in Chapter 16, while modification of the NP is the main topic of Chapter 17; adjectival modifiers are also discussed in Chapters A28 and A32.

Semantically speaking, the NP determines the denotation of the complete noun phrase. A noun such as boekbook can be said to denote a set of entities with certain properties. Restrictive modification of the noun involves a reduction of the set denoted by the noun phrase; for example, the NP erg dik boekvery thick book denotes a subset of the set denoted by boek. The NP-domain itself cannot be held responsible for the fact that noun phrases are commonly used as referring expressions; Subsection II will show that this is the semantic function of the elements constituting the DP-domain.

This subsection briefly discusses the lexical elements found in the DP-domain (determiners, quantifiers and numerals) with special emphasis on the semantic contribution that these elements make, and introduces the so-called predeterminers al and heel, which can be used to modify certain determiners.

In current linguistic theory, determiners and quantifiers/numerals are generally assumed to be external to the NP-domain, and to function as the head of a projection containing the NP-domain, as in (5). Determiners and quantifiers determine the referential and/or the quantificational properties of the noun phrase.

| [DP ... D [NP ... N ...]] |

The determiner slot D can be filled by any of the elements in Table 3.

| neuter noun | common noun | plural noun | |

| articles | het boek the book | een boek a book | ∅ boeken ∅ books |

| demonstrative pronouns | dit/dat boek this/that book | deze/die pen this/that pen | deze/die boeken these/those books |

| possessive NPs and pronouns | Jans/zijn boek Jan’s/his book | mijn moeders/haar pen my mother’s/her pen | onze boeken our books |

| quantifiers and numerals | elk boek each book | elke pen each pen | alle boeken all books |

The assumption that articles, demonstratives and possessive pronouns are located in position D explains why these elements are in complementary distribution, since it is generally accepted that a head position of a phrase can be occupied by only one head. This claim has also led to the hypothesis that the noun phrase may contain other projections besides DP and NP identified in (5); since numerals and specific quantifiers can be combined with articles, demonstratives and possessive pronouns, it is sometimes claimed that they function as the head of a projection, commonly referred to as QP and/or NumP, embedded in DP. This hypothesis would ascribe the more articulate structure in (6) to an example such as mijn vijf broers; cf. Chapter 20 for a more accurate discussion.

| [DP | mijn [NumP | vijf [NP | broers]]] | ||

| [DP | my | five | brothers | ||

| 'my five brothers' | |||||

Although questions about the number of projections involved are obviously of interest (see Alexiadou et al., 2007: part II, for discussion), the main point to remember here is that determiners and quantifiers/numerals are assumed to be external to the NP, which implies that they have no effect on the denotation of the (modified) noun. Their semantic contribution is restricted to the referential and/or quantificational properties of the noun phrase as a whole. Below, we will illustrate this briefly with examples in which the noun phrase acts as the subject of the clause. Before doing so, however, we need to provide some background by briefly outlining the set-theoretic treatment of the subject-predicate relation, which will be central to our discussion of the denotational properties of the NP.

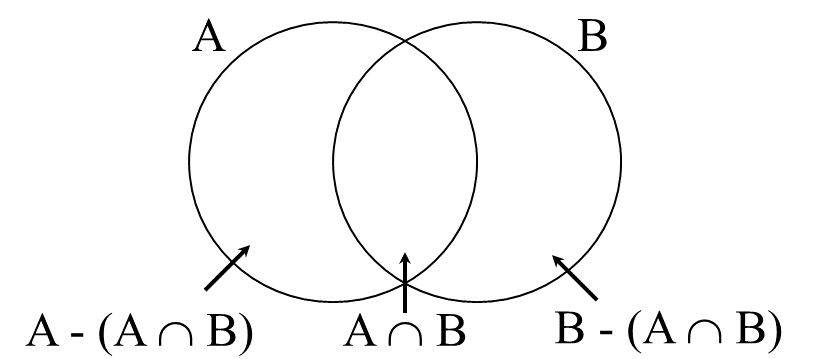

Certain aspects of the meaning of a clause can be expressed by means of set theory. For the sake of illustration, suppose for a moment that a proper noun such as Jan denotes a singleton set (which in fact differs from what is commonly assumed in current formal semantics; cf. Smessaert 2014: 83). Thus, an example such as Jan loopt op straatJan is walking in the street expresses that the singleton set denoted by Jan is contained in the set denoted by the verb phrase loopt op straatwalks in the street. More generally, the subject-predicate relation in a clause can be expressed by Figure 1, where A is the set denoted by (the NP-part of) the noun phrase and B is the set denoted by the verb phrase. The intersection A ∩ B denotes the set of entities for which the proposition expressed by the clause is claimed to be true.

In an example like Jan en Marie wandelen op straatJan and Marie are walking in the street, it is claimed that the complete set denoted by A, viz. {Jan, Marie}, is contained in set B, which consists of the people walking in the street. In other words, it expresses that the intersection (A ∩ B) exhausts set A so that the remainder of set A is empty: |A - (A ∩ B)| = 0; the semantic function of determiners and quantifiers/numerals is to specify the intersection A ∩ B and the remainder of A - (A ∩ B); nothing is said about the remainder of set B, i.e. B - (A ∩ B). Below we will describe this informally for some determiners and quantifiers/numerals. A more complete and formal description can be found in Chapter 20.

The definite article dethe in (7) expresses that in the domain of discourse all entities that satisfy the description of the NP-part of the subject (here: jongen) are included in the intersection A ∩ B, i.e. that A - (A ∩ B) is empty. Therefore the singular noun phrase de jongenthe boy in (7a) has approximately the same interpretation as the proper noun Jan in the discussion above; it expresses that the cardinality of A ∩ B is 1 (for this we will use the notation: |A ∩ B| = 1). The plural example in (7) is usually taken to differ from the singular example only in that it expresses that |A ∩ B| > 1 (although this claim will be slightly adapted in Section 19.1.1.1).

| a. | De jongen | loopt | op straat. | |

| the boy | walks | in the.street |

| b. | De jongens | lopen | op straat. | |

| the boys | walk | in the.street |

The meaning of a definite demonstrative pronoun like dezethis/these and diethat/these or a possessive pronoun like mijnmy is similar to that of the definite article, the only difference being that these determiners effect a partitioning of the set denoted by A; the use of these determiners asserts the claim that one of the resulting subsets is properly included in B (e.g. these boys but not those).

The semantic contribution of the indefinite articles in (8a&b) is to indicate that A ∩ B is not empty, but they imply nothing about the set A - (A ∩ B); the latter may or may not be empty (the other boys in set A may all be in school). The difference between the singular indefinite article een and the (phonetically empty) plural indefinite article ∅ is that the former expresses that |A ∩ B| = 1, while the latter expresses that the cardinality can be greater than 1. From a semantic point of view, the cardinal numerals belong to the same class as the plural indefinite article; an example like (8c) is similar in all respects to (8b), except that it expresses that |A ∩ B| = 2.

| a. | Er | loopt | een jongen | op straat. | |

| there | walks | a boy | in the.street | ||

| 'A boy is walking in the street.' | |||||

| b. | Er | lopen ∅ | jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | boys | in the.street | ||

| 'Boys are walking in the street.' | |||||

| c. | Er | lopen | twee jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | two boys | in the.street | ||

| 'Two boys are walking in the street.' | |||||

The semantic contribution of quantifiers like enkelesome, veelmany and weinigfew can be described in similar terms. The main difference is that the cardinality of the set A ∩ B is somewhat vaguer: an example such as (9a) expresses more or less the same thing as (8b), but in addition the use of enkele suggests that the cardinality of A ∩ B is lower than some implicitly assumed norm “c”: 1 < |A ∩ B| < c. The interpretation of the quantifiers veel and weinig also seems to depend on some implicitly assumed norm: veel expresses that |A ∩ B| > c' and weinig that |A ∩ B| < c''. In the case of enkele in (9a), the implicit norm c still seems more or less fixed; the cardinality of the set of boys walking in the street will never be greater than, say, eight or nine. In the case of veel and weinig, on the other hand, the implicitly assumed norm is contextually determined: a hundred visitors may count as many for a vernissage but as few for a music festival. Note also that, as in the case of indefinite articles and numerals, the examples in (9) do not imply anything about the set A - (A ∩ B).

| a. | Er | lopen | enkele jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | some boys | in the.street | ||

| 'Some boys are walking in the street.' | |||||

| b. | Er | lopen | veel/weinig jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | many/few boys | in the.street | ||

| 'Many/few boys are walking in the street.' | |||||

When we combine a definite determiner and a numeral/quantifier, the meanings of the two are combined. An example such as (10a) expresses that |A ∩ B| = 2, which can be seen as the semantic contribution of the numeral tweetwo, and that A - (A ∩ B) is empty, which can be seen as the semantic contribution of the definite article de. Similarly, (10b) expresses that |A ∩ B| > c, which is the contribution of the quantifier, and that |A - (A ∩ B)| = 0, which is again the contribution of the definite article de.

| a. | De twee jongens | wandelen | op straat. | |

| the two boys | walk | in the.street |

| b. | De vele jongens | wandelen | op straat. | |

| the many boys | walk | in the.street |

Special attention must be paid to a set of expressions often referred to as predeterminers. These expressions are quantifiers that appear in a position left-adjacent to the determiners. Some examples are given in (11), where the determiners mijnmy and dethe in the determiner position are preceded by the predeterminers alall and heelwhole/all of the. Since the semantics of these predeterminers is extremely complex, we will not discuss these elements here but refer the reader to the discussion in Chapter 21.

| a. | al | mijn | boeken | |

| all | my | books |

| b. | heel | de | taart | |

| whole | the | cake | ||

| 'all of the cake' | ||||

Some examples of non-restrictive modification are given in (12): non-restrictive modifiers typically take the form of non-restrictive relative clauses, as in (12a), but they can occasionally also be adjectival or nominal in nature, as in (12b&c). Semantically, non-restrictive modifiers are outside the DP, and thus contain material that is outside the scope of the noun and determiner. In other words, non-restrictive modifiers do not affect the denotation of the NP nor the referential or quantificational properties of the noun phrase as a whole, but merely provide additional information about the referent of the noun phrase. Syntactically, however, the non-restrictive modifiers in (12) clearly belong to the noun phrase, since they occupy the clause-initial position together with the DP (the constituency test).

| a. | Het boek, | dat | ik | graag | wilde | hebben, | was | net | uitverkocht. | |

| the book | that | I | gladly | wanted | have | was | just | sold.out | ||

| 'The book, which I very much wanted to have, had just sold out.' | ||||||||||

| b. | De man, | boos | over zijn behandeling, | diende | een klacht | in. | |

| the man | angry | about his treatment | deposited | a complaint | prt. | ||

| 'The man, who was angry about his treatment, deposited a complaint.' | |||||||

| c. | Het boek, | een eerste druk van Karakter, | werd | verkocht | voor € 10.000. | |

| the book | a first edition of Karakter | was | sold | for € 10,000 |

The previous subsections have shown that the structure of the noun phrase is more or less as indicated in (13a). Leaving aside for the moment certain co-occurrence restrictions and special intonation patterns, this structure allows us to provide a descriptively adequate account of the main word order patterns found within the noun phrase. For example, (13a) predicts that determiners always precede the noun and its adjectival premodifiers and that they can only be preceded by the predeterminers al/heel, i.e. that a numeral or quantifier must follow the determiner (if present). In other words, the structure in (13a) correctly predicts that there are no alternative realizations of the prenominal string al de vier aardige N in example (13b). Similarly, it predicts that an example such as (13b) has no alternative word order pattern for the postnominal PPs: the PP van de Verenigde Staten is the complement of the deverbal noun vertegenwoordigers, and is therefore expected to precede the PP-modifier uit New York.

| a. | [DP al/heel D [NumP/QP Num/Q [NP APMod [N complement] PPMod ]]] |

| b. | al | de | vier | aardige | vertegenwoordigers | van de VS | uit New York | |

| all | the | four | nice | representatives | of the US | from New York |

However, there are many complicating factors. Consider, for instance, the examples in (14) with the deverbal noun behandelingtreatment. The noun phrase Jan in (14a) can be seen as a complement of the head noun, just as it would be a complement of the verb behandelento treat in the clause De dokter behandelt Jan in het ziekenhuisThe doctor treats Jan in the hospital. However ,example (14b) shows that the noun phrase Jan can also be realized as a genitive noun phrase, in which case it precedes the noun behandeling and the attributive adjective langdurigprotracted. To account for this, it is generally assumed that the complement of a noun can also be realized as a genitive noun phrase, which is placed in the determiner position (just like possessive pronouns). For completeness’ sake, note that Section 19.2.2.4, sub I, will show that (unlike English) Dutch exhibits severe restrictions on the noun phrase types that can occur as genitive noun phrases.

| a. | de | langdurige | behandeling | van Jan | in het ziekenhuis | |

| the | protracted | treatment | of Jan | in the hospital |

| b. | Jans | langdurige | behandeling | in het ziekenhuis | |

| Jan’s | protracted | treatment | in the hospital |

A further complication is that the complements of nominal infinitives can also occur in the form of a noun phrase in prenominal position. Nevertheless, example (15a) shows that the unmarked position of the complement is after the attributive adjectives, so we can simply assume that, like the postnominal PP-complements, the prenominal nominal complements must be closer to the head noun than the modifiers; cf. [het [gebruikelijke [tomaten gooien]]].

| a. | Het | gebruikelijke | tomaten | gooien | bleef | niet | uit. | |

| the | customary | tomatoes | throwing | remained | not | prt. | ||

| 'The customary throwing of tomatoes followed.' | ||||||||

| b. | * | Het tomaten gebruikelijke gooien bleef niet uit. |

We refer the reader to Chapter 16 and Chapter 17, respectively, for a more detailed discussion of complementation and modification, as well as the problems concerning word order within noun phrases.